[mashshare]

Nine years ago, I attended a seminar by Ivan Abadjiev, the Bulgarian weightlifting coach who developed a high-intensity program that revolutionized the sport. During the Q&A section, one coach asked Abadjiev at what age athletes could start lifting maximum weights. His answer: 8.

Perplexed, the coach clarified his question by explaining that he meant maximum weights—as in 100 percent. Abadjiev’s answer: 8.

The audience was stunned. After all, medical experts had warned us that heavy weights could permanently damage the growth plates of young athletes, stunting their growth and creating permanent disability. Although Abadjiev’s approach is designed to produce Olympic champions and is quite extreme (involving multiple training sessions per day), there are many benefits to getting young athletes to spend a little time in the weight room. For starters, consider the demands that many of our young athletes go through today—those that only play one sport.

Athlete Development in the Specialization Era

With the appeal of scholarships and pressure to win at all levels, parents are increasingly tempted to encourage their kids to specialize in one sport, year-round. I’ve worked with middle school soccer players who played not only on their school teams but also on at least one year-round club team. These athletes had practice 3-5 times a week and games on the other days—sometimes several games on a Saturday or Sunday. Where I live, rather than trying other sports, these athletes are also encouraged to participate in twice-a-week sport-specific training sessions, where they perform plyometric drills and energy system training. The pressure to specialize continues in high school with what is often called The Recruiting Wars.

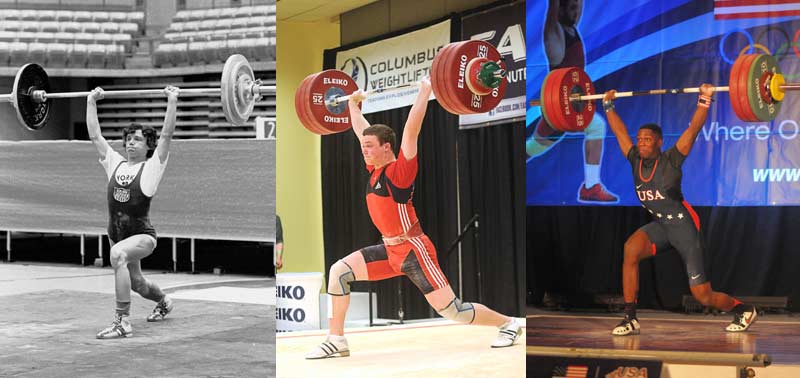

Video 1. Athlete Sierra Cuthill shows good form in the clean and jerk. Cuthill has played soccer, lacrosse, track (high jump and hurdles), and is trained in ballet. She started lifting at the age of 12, and by age 13 increased her vertical jump by nearly 8 inches to a best of 23.3 inches. Cuthill could perform a full snatch and clean and jerk with sound technique the first day she tried! As for academics, she is a straight-A student who is in a magnet program for business.

I know high school track coaches who discourage their star athletes from competing in multiple sports. Instead, the coaches expect them to participate in indoor track and outdoor track while also performing in track camps and demanding summer track workouts.

Likewise, I know high school football coaches who discourage their players from competing in summer track leagues in favor of participating in their strength and conditioning program. The unwillingness to share athletes creates considerable tension among a school’s coaching staff, with the athletes stuck in the middle. Is it any wonder that an estimated 70 percent of young athletes quit organized sports by the age of 13?

Besides the risk of burnout, focusing on one sport makes young athletes more susceptible to injury. One 2017 study of sports specialization involved 1,544 athletes (one-half were female), with an average age of 16 years. Those with a high specialization classification (i.e., focusing on one sport) had an 85 percent higher incidence of lower extremity injury. Yes, 85 percent! The researchers concluded, “Sport specialization appears to be an independent risk factor for injury, as opposed to simply being a function of increased sport exposure.”

Athletes who focused on one sport had an 85% higher incidence of lower limb injury. Weight training helps lower this risk. Share on XSo, what can be done? One answer is to have these athletes participate in a weight training program to help correct muscle imbalances that can lead to injuries.

Why Weight Training? Surveying the Research

One meta-analysis covering 25 studies of sports intervention methods involved 26,610 participants who, as a group, experienced a total of 3,464 injuries. Although athletes are always told to stretch to prevent injury, the researchers found no benefit from stretching. “Our data do not support the use of stretching for injury prevention purposes, neither before or after exercise.” In contrast, the researchers also concluded, “Strength training reduced sports injuries to less than one-third and overuse injuries could be almost halved.” And let’s not forget about concussions.

Studies on American football players show that strengthening the neck can significantly reduce the number of concussions. But there is much more to be gained from weight training than just strength. My strength coaching colleague Paul Gagné presented this year at the “Brains and Brawn Symposium” in Toronto, which focused on the effects of head injuries in sports. His number one takeaway from the symposium was that the best ways to avoid concussions are to avoid contact and learn how to absorb, store, and redirect force.

“Take Wayne Gretzky,” Gagné said. “He was not a big guy or exceptionally strong, but he rarely got hurt—he had the vision to see the game in slow motion and instinctively knew how to move to avoid getting hurt. Likewise, my colleague Ben Velasquez recently visited Cuba, and said the boxing coaches he worked with appear to be following the lead of Floyd Mayweather by placing more emphasis on defensive skills with young boxers, not on increasing punching power.”

The ability to take a punch, Gagné said, is one reason weightlifting is superior to bodybuilding and powerlifting for athletes. “Weightlifters learn how to use the elastic qualities of their tissues to minimize the stress on the body and redirect that stress to produce higher levels of power.” Gagné added that flywheel training, which teaches athletes how to deal with rapid eccentric forces, can also be valuable for injury prevention.

Many SimpliFaster readers are sprint coaches, and I realize that some don’t see much value in weight training. But consider one study that found 27 percent of girls and 29 percent of boys quit sports because of injury (or other health problems). How long do young athletes stay injured? Well, researchers who studied 17 high school track and field teams over one season (77 days), involving 174 males and 83 females, came to this conclusion: “A total of 41 injuries was observed over this period of time. One injury occurred for every 5.8 males and every 7.5 females. On the average, an injury resulted in 8.1 days of missed practice, 8.7 days for males and 6.6 days for females. Sprinting events were responsible for 46% of all injuries.”

When studying these numbers, consider that an injured athlete returning to practice may take at least a week to get back to where they were before the injury. Can you afford to have your athletes miss weeks of practice during the season, lose many more weeks of training getting back in shape, possibly miss several meets, and perform below your expectations? If you can’t, doesn’t it make sense to invest in a little “pre-hab” work in the weight room?

Risks vs. Rewards for Weight Training with Young Athletes

First, understand that 50 years ago, we would not be having this conversation. The only athletes lifting weights were male weightlifters and powerlifters, bodybuilders, and perhaps a few football linemen. (Although off-season training for many football players often was basketball for the “skill” players and wrestling for the linemen).

That was then.

This is now: volleyball players do cleans to improve their vertical jump; baseball players rep out bench presses to hit harder; swimmers perform weighted chin-ups for a more powerful stroke; and hockey players do biceps curls…well, for no apparent reason. Although there are a few holdouts, such as distance runners, many coaches do creative scheduling to accommodate all the athletes who want to pump iron to perform better and prevent injuries.

At this point, the question is not if weight training is an effective way for young people to achieve superior athletic fitness, along with improving self-esteem, but when it’s appropriate to start pumping iron.

Facts and Fallacies of Growth Plates

Perhaps because pretty much anyone can post on Twitter, there is this belief that a high level of stress will stunt an athlete’s growth. Two “real life” examples I hear are that weightlifters are shorter than other athletes of the same bodyweight, and women gymnasts today are much shorter than those in the past. Let’s start with weightlifters.

The perception is that heavy weights compress the spine, causing weightlifters to get shorter as they get stronger. Russian research apparently supports this belief, showing that more experienced weightlifters tend to be considerably shorter than inexperienced ones in the same bodyweight class. Nice try. The reason elite weightlifters are shorter than other athletes of the same bodyweight is that they carry more muscle mass!

Elite female gymnasts—athletes who certainly place a high level of stress on their body—tend to be short compared to other female athletes, but for a different reason. Thirty years ago, the average elite female gymnast was 5-foot-3; now the average is 4-foot-9. Simone Biles, one of the greatest (if not the greatest) gymnasts in the history of the sport, is just 4-foot-8. The current level of competition is so high and the movements are so difficult that shorter athletes have an advantage because:

- Their stability is better

- They can rotate faster

- They have greater relative strength

The point here is that if you’re going to go with the idea that gymnastics training makes athletes shorter, it follows that playing basketball will make athletes taller because there are so many tall players in the NBA! With that nonsense dismissed, let’s look at some research addressing the fear that weight training stunts a young athlete’s growth by closing their growth (epiphyseal) plates.

First, premature closing of the growth plates is usually caused by hormonal influences, not injury. In the rare incident that a child injures a growth plate, the bone could certainly become deformed, but it will still grow.

One champion of young athletes pumping iron was the late Mel Siff, Ph.D., an outspoken exercise scientist whose doctorate thesis looked at the biomechanics of soft tissues. In his book, Facts and Fallacies of Fitness, Siff said this about growth plates: “Epidemiological studies using bone scans by orthopedists have not shown any greater incidence of epiphyseal damage among children who lift weights. On the contrary, bone scans of children who have done regular competitive lifting reveal a significantly larger bone density than those who do not lift weights. In other words, controlled progressive competitive lifting may be useful in improving the ability of youngsters to cope with the rigors of other sports and normal daily life.” Siff went on to explain what he meant by the “rigors of other sports.”

“Considerable biomechanical research has shown that the stresses imposed on the body by common sporting activities such as running, jumping and hitting generally are far larger (by as much as 300%) than those imposed by Powerlifting or Olympic Lifting,” Siff said. “In other words, the stresses imposed on the growth centres of the growing child’s body are markedly greater than those occurring in competitive lifting [sic]. If we well-meaningly think that potential growth plate damage is to be minimized, then we need to pay even greater attention to any sports which involve running, jumping, or hitting.”

What do today’s experts believe about the safety of weight training? Well, the results of a survey published in 2013 asked 500 experts in sports medicine if they agreed with the statement that weight training should be avoided until epiphyseal closure. “Overall, respondents answered that ‘this statement is very likely false,'” noted the researchers. “In sum, the expert consensus from our survey that strength training is safe for individuals with immature skeletons is consistent with data from medical literature.”

Why Serious Athletes Must Lift

Running and jumping are two basic components of athletic fitness, which is why many coaches supplement their athlete’s training with plyometrics. With sprinters, I found that if there’s a choice between plyos and lifting, their coaches will often choose plyos. In fact, in 1984 I asked Carl Lewis if he lifted, and he said that his coach often gave him a choice between plyos and lifting, and he chose plyos.

Can plyometrics help an athlete run faster and jump higher? Certainly, but the research shows that weight training can also do this and may do it faster—especially in the early stages of an athlete’s career.

In one eight-week study that compared weight training to plyometrics for improving the vertical jump, the weight training group did better—even though vertical jumping was part of the plyometric group’s training. Refining this idea, researchers have also looked at which is better for developing explosiveness: powerlifting or weightlifting.

In another study comparing weightlifting exercises to powerlifting, the weightlifters had superior improvements in the vertical jump. The researchers also tested the athletes’ power by having them perform vertical jumps with an additional 20 kilos/44 pounds and 40 kilos/88 pounds. Again, the weightlifters produced superior results, perhaps because the weightlifting stressed the elastic qualities of the tissues more effectively than powerlifting.

Young athletes who weightlifted jumped higher and sprinted faster. Share on XAs for sprinting ability, a 15-week study of 20 collegiate football players found that, compared to the powerlifting group, those players using weightlifting saw a “twofold greater improvement in 40-yard sprint time.” Yes, sprinters need to sprint, but if the goal is to fulfill an athlete’s physical potential, then shouldn’t a coach consider all available resources to make an athlete faster? And if strength didn’t matter for sprinting, why were so many elite sprinters caught for steroids? Just sayin’.

I often hear the statement, “A child is not a small adult, so don’t train them like one.” A better statement is, “You can’t have a specific program for a single age group because young people mature at different rates.” In a class of 12-year-old boys, some boys may have the physical maturity of an 11-year-old boy, and some a 12-, 13-, or even 14-year-old boy. Take the case of 2020 Olympic hopeful CJ Cummings.

Cummings began lifting at the age of 10. At age 11, he clean and jerked double bodyweight. Three years later, he clean and jerked an American record of 337 pounds to break the senior American record in the 136-pound bodyweight class, and last year he clean and jerked a junior world record of 425 pounds in the 160-pound bodyweight class. Certainly, CJ is an outlier in terms of physical maturity.

Unfortunately, many of the weight training workouts I’ve seen for kids are rather lame, doing little to develop strength, and few even consider teaching weightlifting (i.e., the snatch and the clean and jerk). Why am I a champion for weightlifting movements?

Weightlifting develops strength through a large range of motion, thus improving flexibility and stability. In fact, the overhead squat, which at the bottom is the catch position of a snatch, is one so-called functional screen used to determine flexibility and muscular imbalances. As for addressing the matter of risk versus reward, here are several proven benefits of performing the full lifts:

- Strength (relative, absolute, speed/explosive)

- Jumping ability (vertical, horizontal)

- Short sprint speed

- Muscle mass

- Reduced body fat

- Muscular endurance

- Core strength

- Cardiovascular health

- Postural alignment

- Body awareness

- Reduced risk of injuries

That’s a lot of bang for your buck, such that the rewards they offer are certainly worth the risks associated with practicing them. Short on time? Do some clean and jerks and back squats, and you’ll address many of the goals of a strength and conditioning training program. But even a more complete lifting program doesn’t take as much time as you might think.

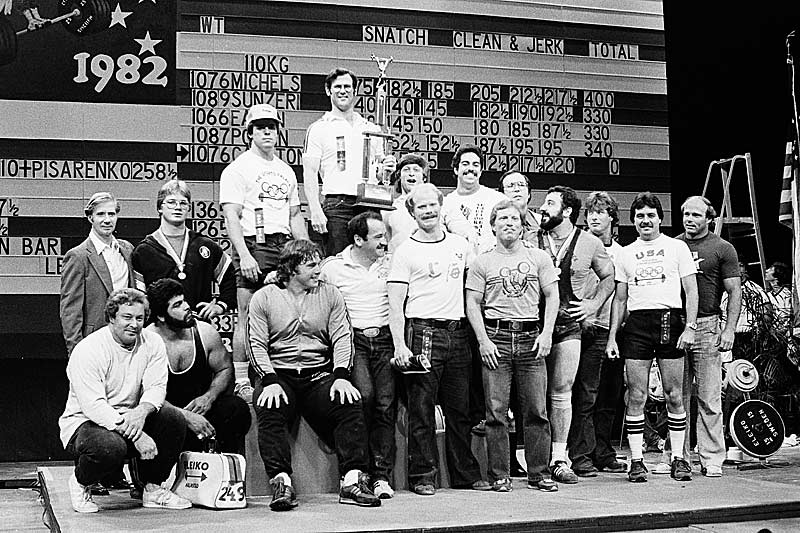

My weightlifting coach was Jim Schmitz, a 3x USA Team Coach for the Olympic Games. Schmitz’s Sports Palace Team won nine straight team titles at the Senior Nationals, and he coached athletes in seven Olympic Games. His athletes trained just 3x a week, about 90-120 minutes per session, Monday, Wednesday, and Friday—that’s it!

Why are so many coaches reluctant to perform the full Olympic lifts, preferring (if anything) the inferior partial-range variations, such as hang cleans? One reason so many coaches dislike weightlifting is because they believe the Olympic lifts performed from the floor are too difficult to teach. I agree that the full weightlifting movements are too hard to teach—if you don’t know how to teach them!

I’ve been involved in weightlifting for over four decades, and it’s rare when I cannot teach a decent male athlete how to perform a respectable power clean from the floor in about 15 minutes. And with females, it takes about that long to teach most of them a squat clean. Many of my weightlifting colleagues can do the same.

I often see good athletes learn to do technically sound clean and jerks, and sometimes snatches, during their first training session. Share on XYes, full lifts take longer to master, but often I see good athletes doing technically sound clean and jerks, and sometimes snatches, during their first training session. For example, below is a video of a female multi-sport athlete learning how to snatch for the first time—she did a dozen sets, and the entire session took about 25 minutes. Rather than badmouthing these lifts, coaches should meet with an experienced weightlifting coach and ask them to show how to teach these valuable lifts.

Video 2. For those who believe the Olympic lifts are too difficult to learn, here is multi-sport athlete Samantha Dwyer performing the full snatch for the first time. This workout took about 25 minutes.

Can athletes reach a high level of athletic performance without lifting weights? Certainly. It’s the nature of sport that, all things being equal, talent prevails. Usain Bolt lifted weights, but the workout I saw him doing on YouTube leads me to believe that Bolt is fast despite his lifting program rather than because of it. Likewise, the success of many college sports programs is strongly influenced by recruiting. In contrast, at the high school level where recruiting is not an option (except for some private schools), you have to make the best of what you’ve got.

Final Thoughts

I agree that some young athletes don’t have the emotional maturity to train in a weight room safely—these athletes don’t belong in a weight room. It’s also true that some coaches don’t have the skills to teach weight training properly—these coaches don’t belong there either. As Spiderman would say, “With the great power that can be developed in the weight room comes great responsibility!”

It’s true that a sound weight training program may not transform a mediocre athlete into a superior athlete, but it can help all young athletes perform better and be less susceptible to injury. As General George S. Patton said, “You can never be too strong!”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Brenner, JS. and Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. “Sports Specialization and Intensive Training in Young Athletes.” Pediatrics, Vol. 138:3, September 2016.

American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. “Sports specialization may lead to more lower extremity injuries.” ScienceDaily, July 23, 2017.

Hislop, MD, et al. “Reducing musculoskeletal injury and concussion risk in schoolboy rugby players with a pre-activity movement control exercise programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, Vol. 51:1140–1146, 2017.

Milone, MT, et al. “There is no need to avoid resistance training (weight lifting) until physeal closure.” Physician and Sports Medicine, Vol. 41(4): 101-5, November 2013.

Lauersen, JB., et al. “The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, Vol. 48(11):871-7, June 2014.

Kelley, B., and Carchia, C. “Hey, data data—swing!” ESPN.com, July 11, 2013.

Watson, MD, and DiMartino, PP. “Incidence of injuries in high school track and field athletes and its relation to performance ability.” American Journal of Sports Medicine, Vol. 15(3):251-4, May-Jun 1987.

Siff, M. Facts and Fallacies of Fitness, (4th edition, 2000), 154-156.

McBride JM, et al. “A comparison of strength and power characteristics between power lifter, olympic lifters, and sprinters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, Vol. 13(1):58–66, 1999.

Hoffman, JR, et al. “Comparison of olympic vs. traditional power lifting training program in football players.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, Vol. 18(1):129-135, February 2004.