In the 1968 Olympics, US weightlifter Tommy Suggs noticed that Russian coaches had a unique way of greeting athletes from other countries. They would shake with one hand and then reach around with the other to feel the thickness of their lower back muscles. Such was the importance these coaches placed on developing this muscle group.

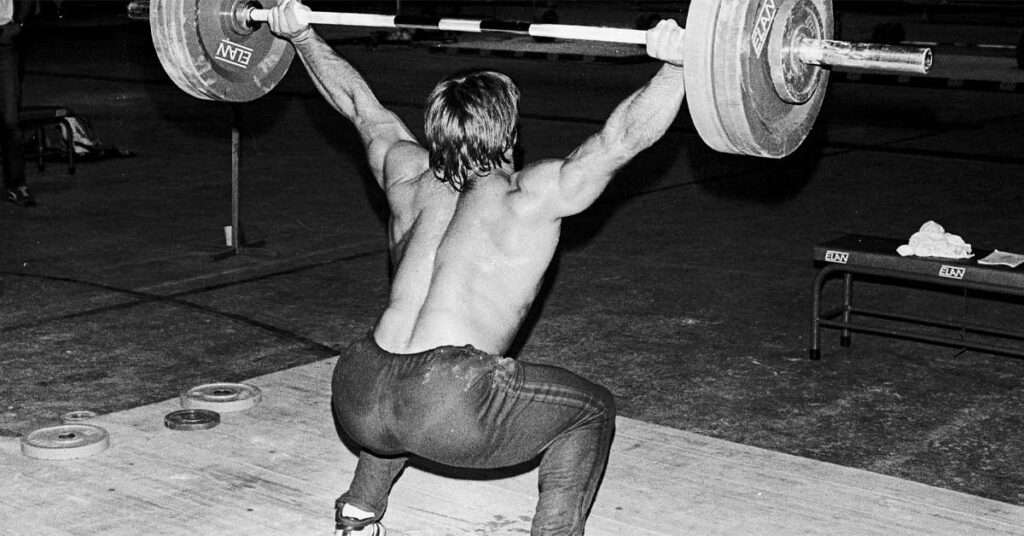

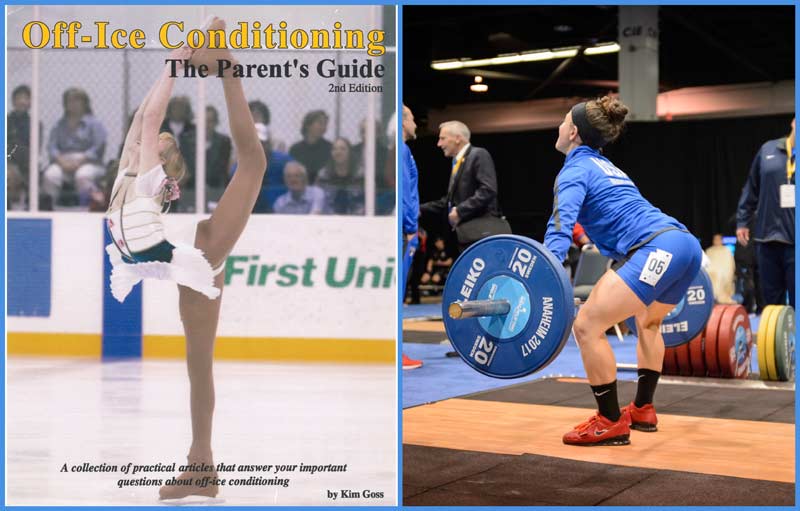

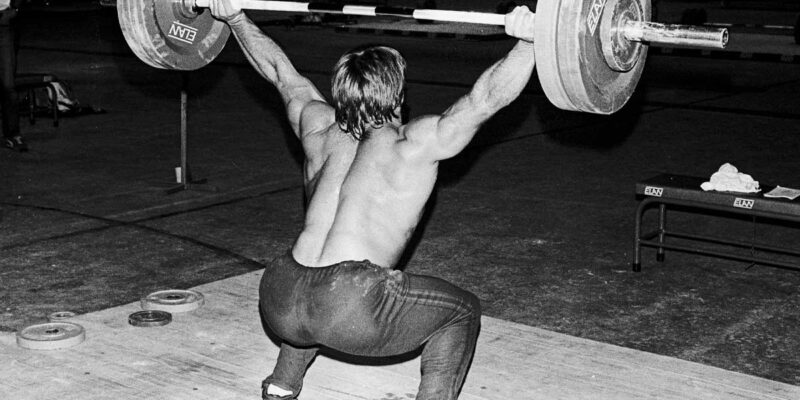

In review, the erector spinae consist of three muscles that run vertically along both sides of the spine: iliocostalis, longissimus, and spinalis. Their functions include extension, flexion, and rotation of the torso. These muscles are also involved in spinal stability. As seen in the lead photo of the US Olympian Derrick Crass (photo by Bruce Klemens), fully developed erector spinae muscles resemble a pair of thick cables.

Strength coach Charles R. Poliquin believed that strong erector spinae muscles created an “irradiation effect,” such that if you strengthen these muscles, your strength in other lifts will improve. For example, Poliquin said performing barbell back extensions could enable you to lift more in the military press and the biceps curl. Spine biomechanics professor Dr. Stuart McGill agrees.

“Stiffening the core allows the hip and shoulder musculature to move the distal limbs without an energy leak as the spine bends,” says McGill. “A core that arrests spine movement transfers the power generated at the hips to use in Olympic lifts, military presses, and the like.” McGill adds that he has worked with elite weightlifters and world record holders in powerlifting, and the common factor among them was a “strong, stiffening core.”

Before getting into the pros and cons of various lower back exercises, let’s look at two sports that have taken a particular interest in developing the erector spinae muscles: powerlifting and weightlifting.

Getting “Back” into Powerlifting

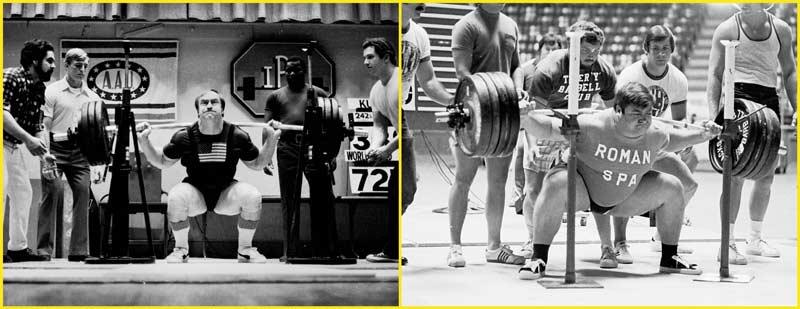

In the early days of powerlifting, minimal “supportive gear” was allowed. Today, numerous powerlifting federations permit the use of gear such as squat suits that may add hundreds of pounds to a lifter’s performance. Whereas 700-pound bench presses and 900-pound squats are rare in one federation, 1000+ results in these lifts are commonplace in others. Beyond gear, there was the issue of technique.

Some powerlifters would squat with an upright style and a relatively narrow foot stance a half-century ago, a style that could be considered “quad-dominant.” However, allowing athletes to squat higher and wear special squat suits that support the spine has resulted in the popularity of a lift that resembles an ultrawide stance good morning. This style could be considered “hip-dominant.”

Allowing athletes to squat higher and wear special squat suits that support the spine has resulted in the popularity of a lift that resembles an ultrawide stance good morning. Share on X

I discussed this new squatting technique with the late Carl Miller, a former coaching coordinator for USA Weightlifting who did extensive academic work in anatomy. Miller offered the theory that powerlifters figured that the knees would wear out before the hips, so they developed a squatting technique that would place more emphasis on the hips than the knees. He presents an interesting argument because there has been a significant increase in hip replacement surgeries among the general population in recent years. In other words, because knee replacement surgeries have become so effective, the hip is the next area to break down.

This technique may be better for boosting the numbers in powerlifting competitions, but this muscular imbalance may be a red flag for athletes in other sports. Just ask strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné.

Putting more emphasis on the hips than the knees may be better for boosting the numbers in powerlifting competitions, but this muscular imbalance may be a red flag for athletes in other sports. Share on XGagné recently consulted with an NFL team that focused on partial squatting movements. He noticed that many of these athletes “were built like horses,” with considerable muscle mass around the hips and upper thighs and minimal development of the muscles around the knee. He believes such unbalanced development increases the risk of knee injuries.

As for how modern powerlifters should train, no discussion about powerlifting would be complete without a mention of Louie Simmons, one of the most influential coaches in powerlifting.

Although the squat and deadlift work the erector spinae muscles, Simmons believed that powerlifters should perform additional work for the lower back. One of his key predictor lifts was the standing good morning. Among Simmons’ influences was Bruce Randall, a strongman who bulked up to 401 pounds and could perform a good morning with 685 pounds. From there, Randall dropped nearly half his bodyweight to become Mr. Universe in 1959.

The Russian weightlifters in the 60s and 70s also performed good mornings for strength with a barbell on the shoulders. Leonid Taranenko is a former absolute world record holder in the clean and jerk with a best of 586 pounds in 1988, a record that stood for 33 years. In an interview with weightlifting sports scientist Bud Charniga, Taranenko said he would perform the exercise because he believed it was important to have a strong back in weightlifting. With the good morning, athletes lean forward, allowing their hips to shoot back to maintain their balance. Taranenko said he would straighten up when he felt pressure on the balls of his feet.

Many commercial gyms offer seated back extension machines that replicate the movement of a seated good morning. I believe the seated variations should probably be avoided by those with a history of lower back issues.

Seated good morning variations should probably be avoided by those with a history of lower back issues. Share on XI say this because research conducted by Alf Nachemson of Sweden in 1975 showed that leaning forward about 15 degrees from a seated position can nearly double the compressive forces on the L2-3 vertebrae. In fact, about 30 years ago, a friend of mine with a history of lower back pain told me he decided to try such a machine. After performing just one set, he immediately had to be taken to the emergency room for severe muscle spasms that prevented him from walking.

As the powerlifting community focused on using the lower back muscles more in squatting, the weightlifting community was developing methods to use the lower back less, making additional work unnecessary.

A Tale of Two Pulling Techniques

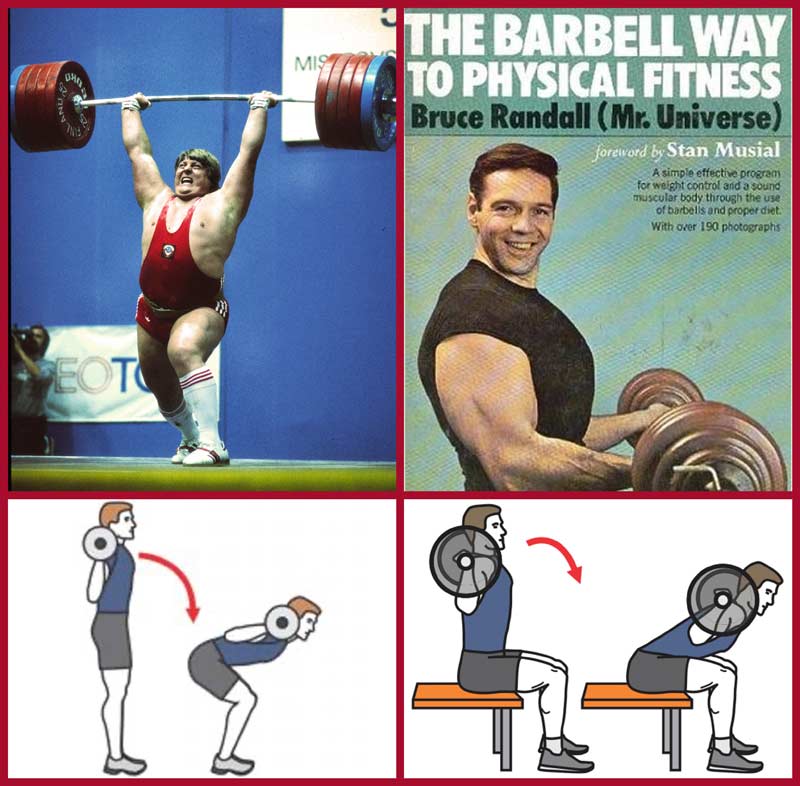

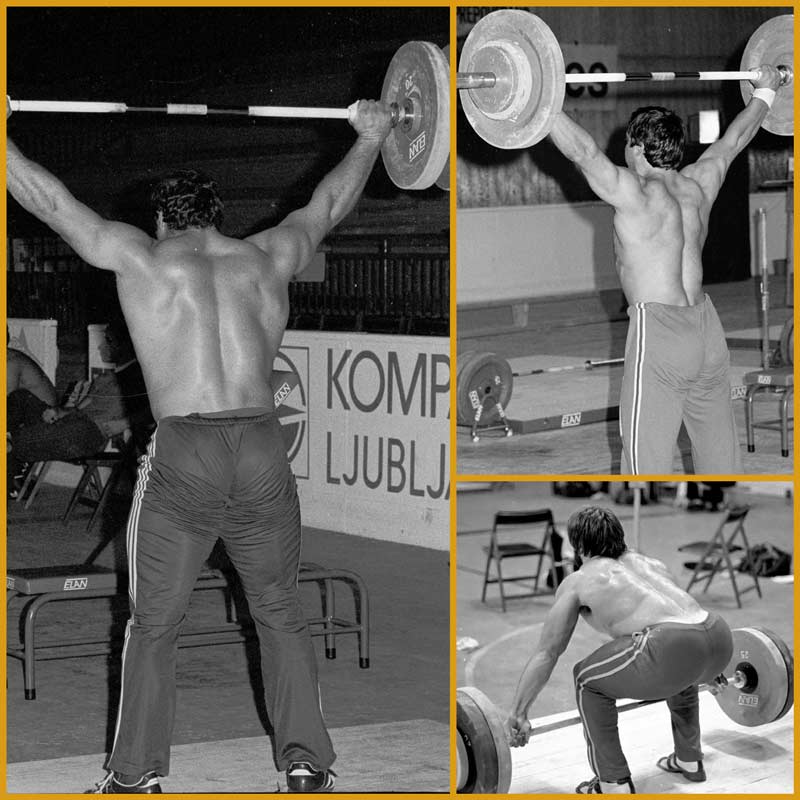

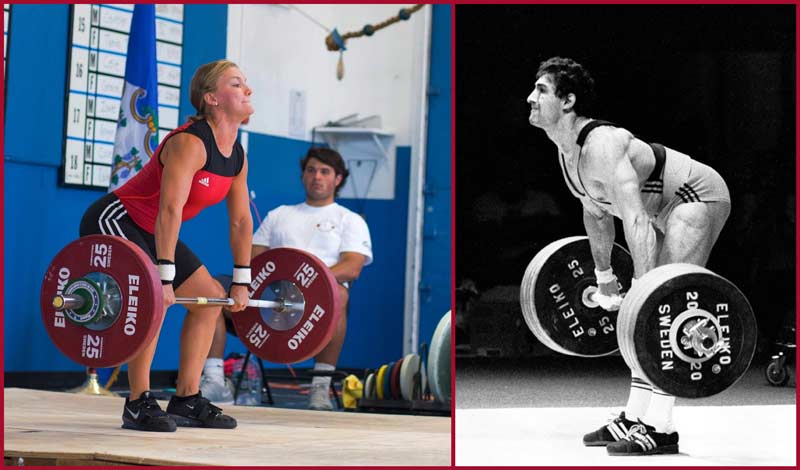

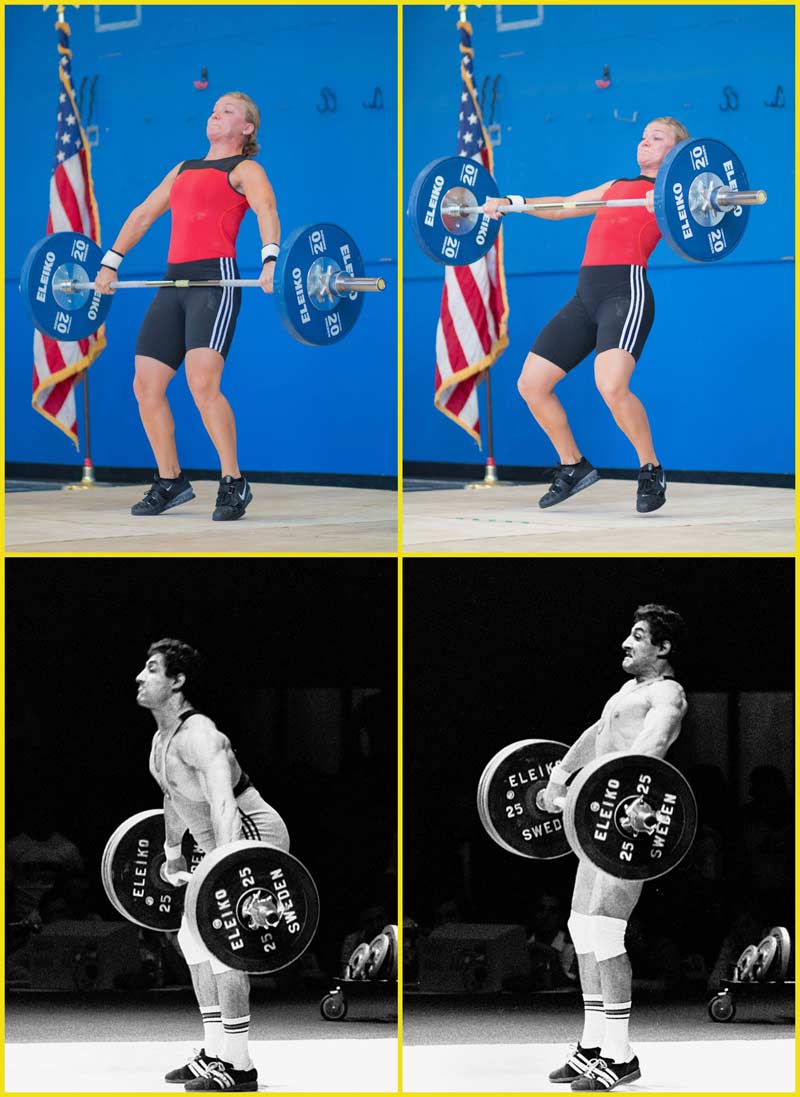

In the 60s, Russia was the dominant force in weightlifting. Their coaches promoted a lifting style that extended the shoulders well in front of the bar when it passed the knees.

In the 60s, Russia was the dominant force in weightlifting. Their coaches promoted a lifting style that extended the shoulders well in front of the bar when it passed the knees. Share on XThe Russian technique places a high level of stress on the spine for a prolonged period. Focusing on this technique resulted in these athletes developing tremendous erector spinae muscles, and they often included special exercises to strengthen the lower back.

In 1984, unnaturally high testosterone levels among athletes resulted in a doping ban for this hormone. Doping control affected lifters using the Russian pulling style because they could not recover adequately from the stress this technique placed on the lower back, at least not with the total volume of their training that they were accustomed to (for more on the triple extension technique, see my article).

In the early 80s, the Chinese took a particular interest in weightlifting, especially in the women’s division. They “changed the game” by looking for ways to modify pulling techniques to minimize the stress on the lower back for women. The style was more upright, with the shoulders staying on top of the bar during the pull throughout the lift.

Chinese weightlifters 'changed the game' by looking for ways to modify pulling techniques to minimize the stress on the lower back for women. Share on X

The Chinese pull has a distinct advantage over triple extension because it uses the powerful Achilles tendon to assist the quads in producing power. Thus, their lifters raised their heels before full knee extension. They also avoid moving the shoulders in front of the knees at any point of the lift. As such, additional lower back exercises were unnecessary, and lifters could perform a higher volume of the classical lifts (e.g., snatch or clean and jerk). And because females tend to have relatively more strength in their legs than their lower backs (compared to men), this style proved superior.

As a result of this pulling technique, the Chinese women have been the dominant force in the Olympic and World Championships. In recent years, Chinese men have become an international powerhouse in the lighter bodyweight classes but struggle to find talent in the heavier classes. That said, if the Chinese enter a lifter in an international competition, odds are they will medal. Often, one or more of them will break a world record.

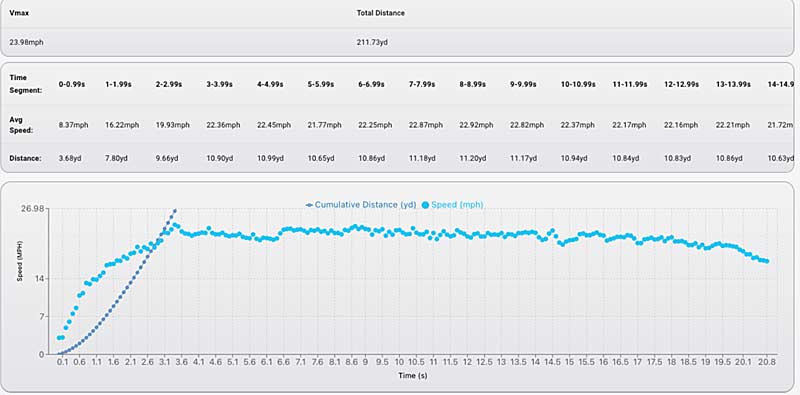

Modern technology allows coaches to analyze a weightlifter’s technique more precisely. Video 1 shows my former weightlifter, Christian Rivera. The first image was taken when we started working together and shows that he was pulling the bar straight up rather than towards his center of mass. The next clip shows a corrective exercise for this issue, followed by a lift with a more optimal bar path and a heavy lift in competition. At a bodyweight of 143 pounds, Christian broke the New England clean and jerk record with a lift of 288 pounds.

Video 1. Using bar path software to help coaches correct an athlete’s lifting technique. (Final video clip by LiftingLife.com.)

Today, perhaps due to a lack of education and gyms being overwhelmed with athletes, many strength coaches only have their athletes perform Olympic lifts from the mid-thigh (hang) or blocks—the so-called “weightlifting derivatives.” These variations minimize the stress on the lower back from pulling off the floor. It also means the lower back muscles received little stimulation.

Today, perhaps due to a lack of education and gyms being overwhelmed with athletes, many strength coaches only have their athletes perform Olympic lifts from the mid-thigh (hang) or blocks. Share on XBesides these partial movements, many popular strength and conditioning programs focus on Bulgarian split squats, high hex bar deadlifts, and leg presses that do little to develop the lower back muscles. Athletes who focus on these lifts could benefit from additional exercises for the erector spinae This begs the question: “Which ones are the best?”

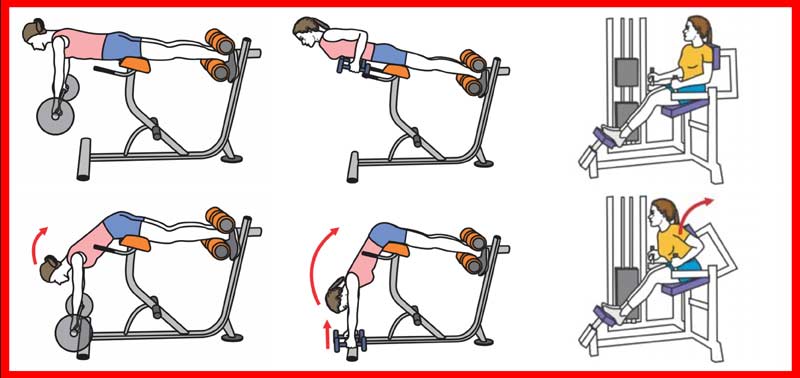

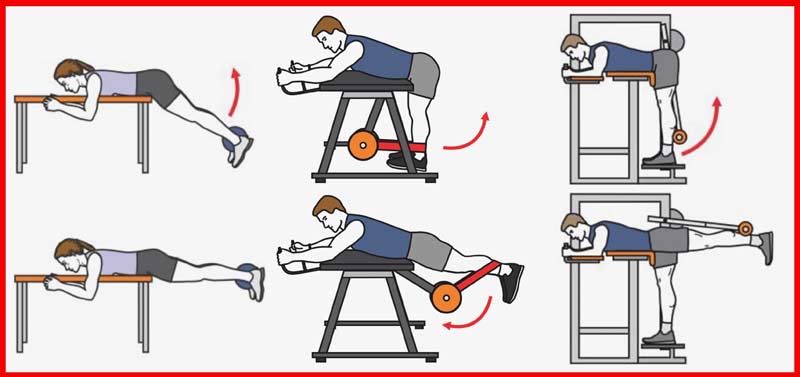

There are two major types of lower back exercises: those producing maximal resistance in the internal range (back extensions) and those producing maximal tension in the external range (reverse hypers and good mornings). Let’s start with back extensions.

Rediscovering Back Extensions

Back extensions strengthen the erector spinae muscles in the internal (shortened) range and strongly affect the gluteal muscles.

First, consider that back extensions can be used as a dynamic warm-up for the posterior chain muscles (hamstrings, glutes, lower back) at the beginning of a workout. In the 70s, I would train alongside Ken Clark at the Sports Palace Gym. Clark was an Olympian who clean and jerked 470 pounds in the 220-pound bodyweight class, a lift that I believe has yet to be matched. He would warm up with a few bodyweight back extensions before lifting.

By changing the angle of the bench (horizontal to incline), you can affect different portions of the strength curve, so variation ensures complete development of the muscles. Resistance can be increased by holding a weight plate across your chest and on your shoulders or a barbell across your shoulders, but having a barbell is more comfortable and you can pack on the plates.

Coach Poliquin liked performing back extensions on a 45-degree incline bench, holding the barbell at arm’s length (arms perpendicular to the floor) with a wide grip to increase the range of motion. From a muscle recruitment standpoint, Gagné says incline back extensions recruit more of the muscles below the L3 vertebrae, and conventional back extensions recruit more of the muscles above L3.

Incline back extensions recruit more of the muscles below the L3 vertebrae, and conventional back extensions recruit more of the muscles above L3. Share on X

The Reverse Hyper Advantage

Reverse hypers strengthen the erector spinae muscles in the external (lengthened) range and strongly affect the gluteal muscles. Poliquin told me he saw gymnastic coaching books from east Germany and Hungary showing this exercise performed with resistance over a pommel horse. Resistance was provided by a kettlebell or a medicine ball. I’ve also seen a physical training book by Thomas DeLorme and Arthur Watkins, published in 1951, showing the exercise performed with iron boots. The 1985 German physiotherapy book Training Therapy: Prophylaxis and Rehabilitation, by Rolf Gustavsen and Renate Streeck, shows the performance of this exercise using cables for resistance.

Another interesting variation was performed by American weightlifter Roger Quinn. Chronic knees prevented Quinn from squatting heavily frequently. As such, he would focus on the Olympic lifts and then substitute a combination of other exercises for squats. One of these was a reverse hyper variation using manual resistance.

Quinn describes this exercise in an article published in the March 1974 issue of the International Olympic Lifter. He would lie face down over a gymnastic pommel horse and, while keeping his legs straight, Quinn would have one training partner apply manual resistance to his legs while another stabilized his upper body. “These reverse hyperextensions…seem to work the buttock muscles in the same fashion that the two-hand curl works the biceps,” said Quinn. “I feel that this exercise comes close to really isolating the buttocks while simultaneously employing the spinal erector muscles of the lower back.”

As for the first working prototypes of a reverse hyper machine, powerlifting guru Louie Simmons received the first patent on a device in 1993. Simmons also suffered a back injury and sought to rehab it by developing a reverse hyperextension machine. Resistance was applied by a strap that wrapped around the ankle; the strap was attached to a lever arm with a pivot point under the bench. This design enabled the legs to be pulled in line with and even under the hips, increasing the exercise’s range of motion and thus providing traction on the erector spinae.

According to Gagné, reverse hypers are among the best exercises for the erector spinae—particularly for those athletes with postural problems—as they work these muscles in the external (lengthened) range. “About 90 percent of the professional hockey players I coach have an excessive anterior tilt of the pelvis and chronic tightness in the lower back. They must focus on working the lower back with a neutral spine and only in the external range.”

Gagné also says the biggest and most common mistake when performing reverse hypers is lifting the legs horizontally (on the units with a platform parallel to the floor). Raising the feet to parallel or even higher, as many powerlifters recommend, will place adverse stress on the L3 to L5 vertebrae by causing the spine to hyperextend.”

Regarding kettlebell swings, which are external-range exercises, you must be careful to maintain a neutral spine when performing them. Often, the momentum these weights develop can encourage back rounding and take the tissues through a range of motion that may be too extreme. Also, don’t rely on a picture book to learn these exercises—seek the help of a qualified instructor.

As for reps and sets, because the erector spinae are primarily slow-twitch muscle fibers, coach Poliquin says you should perform phases of high-rep and low-rep protocols. The low reps will help with performance in heavy compound exercises such as squats, and the higher reps are essential to help prevent and rehabilitate lower back issues caused by poor muscular endurance.

The Issue is the Tissue!

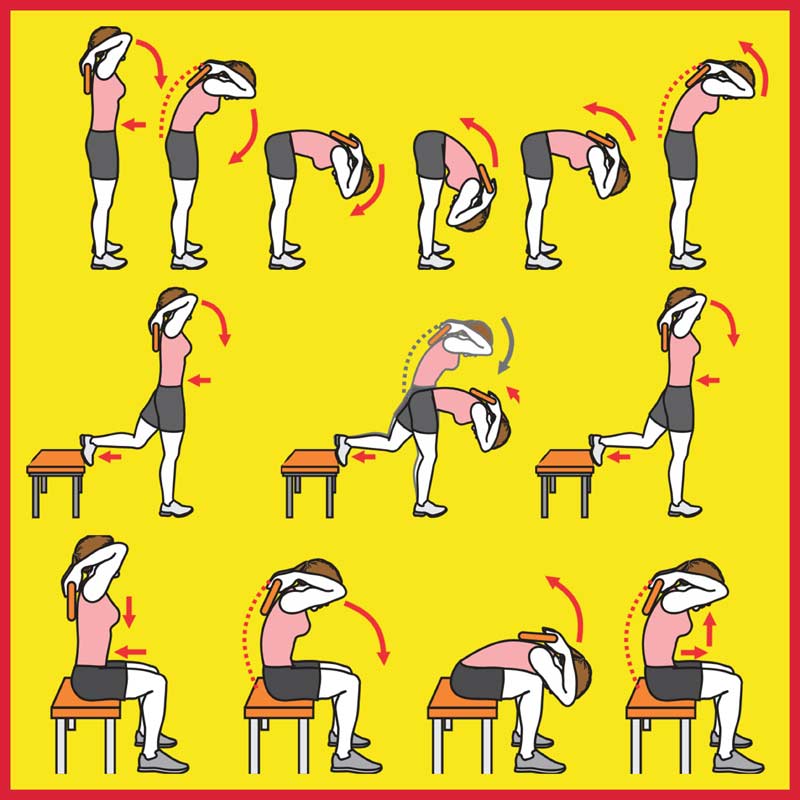

Besides being used as a strength training exercise for the lower back, the Russians used several variations of good mornings and back extensions with light weights as a prophylactic/therapeutic exercise. Consider these as dynamic stretches.

Think about it: how many basic weight training exercises are performed with a “tight back,” such as a squat, deadlift, or power clean? Performing an exercise with a rounded back with a light weight (usually the empty bar) will help ease the tension developed during these exercises.

Performing an exercise with a rounded back with a light weight (usually the empty bar) will help ease the tension developed during these exercises. Share on XIn 1974, weightlifting legend Tommy Kono wrote an article for Strength and Health magazine where he said that hard weightlifting training can cause the lumbar muscles to become overworked, such that they become stiff and “cannot relax or tighten completely.” He added, “Your back can become ‘stiff as a board’ with the lumbar muscles hard to the touch (‘all knotted up’), or the muscles so fatigued that it is like a spring that has been overstretched. In either case, you have lost the explosive contractile quality of the muscles in the lower back.”

The late Dr. Mel Siff told me this idea was often used in figure skating. After arching their lower back in a Biellmann spin (where the skater pulls the heel of their boot behind their head into a split), in practice, skaters would be instructed to touch their toes to prevent their back from cramping.

In 1986, weightlifting sports scientist Bud Charniga wrote an article about a rounded-back good morning holding a barbell. Using an empty bar, the athlete would bend forward and try to touch their head to their knees (shifting their hips back to maintain balance). Performing this exercise with just an empty barbell is extremely difficult.

As a compromise, I would often have my sprinters at Brown University perform it by holding a light weight plate (usually 10 pounds for females and 25 pounds for males) behind their shoulders, going down as far as comfortable. I would have them perform the exercise standing, with the rear foot elevated in a split, and seated. These were performed with light weights and only as a dynamic stretch. However, those with disc issues could aggravate their condition with these movements.

An alternative to these types of dynamic stretches is longitudinal osteoarticular decoaptation stretching, which is translated from the French acronym ELDOA. ELDOA is a form of fascia stretching developed by Dr. Guy Voyer that decompresses the entire spine and helps normalize the alignment of the vertebrae.

ELDOA is a form of fascia stretching developed by Dr. Guy Voyer that decompresses the entire spine and helps normalize the alignment of the vertebrae. Share on XThrough extensive research involving sophisticated diagnostic equipment, Voyer demonstrated that ELDOA can increase the space between each vertebral column segmentally; but rather than just muscles, ELDOA stretches the fascia.

Fascia is the tissue that connects and shapes every muscle, organ, blood vessel, and nerve. Of particular importance to athletes is that fascia envelopes and intertwines with the fibers of muscles and, therefore, plays a vital role in determining the range of motion of each joint. In effect, if the fascia is abnormal or injured, an athlete will never achieve optimal levels of flexibility, strength, and power, no matter how much static, PNF, or dynamic stretching they perform.

ELDOA is remarkably effective in treating herniated disks and back pain caused by many other conditions. As a bonus, one effect of myofascial stretching and ELDOA is an increased ability to recover from exercise. This effect enables athletes to increase the intensity and length of their conditioning programs and sports training sessions. Video 2 shows a tennis player who was coached by Gagné performing an ELDOA stretch for the lower back.

Video 2: A tennis player performing an ELDOA stretch that decompresses the vertebrae. (Video by Paul Gagné.)

Finally, the current thinking in back pain rehabilitation appears to be that muscular endurance may be more important than absolute strength. For more on this subject, I highly recommend Dr. Stuart McGill’s extensively researched but highly readable textbook, Low Back Disorders, 3rd Edition.

I realize I’ve thrown a lot of controversial ideas at you, but what worked a half-century ago in strength coaching may not be what’s best for athletes today. It’s been said that “the Devil is in the details,” so stay on top of your game and take a closer look at lower back training.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Reed, D. Personal Communication about Tommy Suggs. 1976.

Poliquin, C. The Poliquin Principles, 3rd Edition. Poliquin Performance Center 2, LLC. 2016; p. 142.

McGill, S. Personal Communication. August 27, 2023.

Miller, C. Personal Communication. 2005.

Roach, R. “The Amazing Transformation of Bruce Randall.” Iron Game History. 2008;10(3) (Reprinted from Muscle, Smoke & Mirrors; House Publishing, 2008).

Charniga, A., Jr. “An Interview with Leonid Taranenko.” Sportivny Press. September 23, 1989.

Nachemson, A. “Disc Pressure Measurements.” Rheumatology Rehabilitation. 1975;14(3):129-43.

Charniga, A., Jr. “Can There Be Such a Thing as an Asian Pull?” European Weightlifting Federation Scientific Magazine. 2016;2(4):24-32.

Charniga, A., Jr., “The Ankle and the Asian Pull.” European Weightlifting Federation Scientific Magazine. No 12: January-April 2017.

DeLorme, T., and Watkins, A. Progressive Resistance Exercise. Appleton-Century-Crofts, Inc. 1951.

Gustavsen, R., and Streeck, R. Training Therapy: Prophylaxis and Rehabilitation. Thieme Medical Publishers. 1985.

Quinn, R. “My Special Leg Routine.” International Olympic Lifter. 1974;1(3).

Kono, T. “The Loosening Deadlift.” Strength and Health. 1974.

Charniga, A., Jr. “Variations and Rational Use of the Good Morning Exercise.” NSCA Journal. 1986;8(1):74-77.

Goss, K. “New Directions in Sports Training and Rehabilitation.” Bigger Faster Stronger. Jan-Feb 2007.

McGill, S. Low Back Disorders: Evidence-Based Prevention and Rehabilitation, 3rd Edition. Human Kinetics. May 8, 2015.

Alex Roberts is the Strength and Conditioning Coach at R. Nelson Snider High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this role, he’s responsible for the year-round athletic development of all student-athletes. Coach Roberts’ main responsibilities are teaching strength training classes during the school day, leading after-school training sessions, and running the summer strength and conditioning program. He holds a Master of Science in Kinesiology and is CSCS certified through the NSCA.

Alex Roberts is the Strength and Conditioning Coach at R. Nelson Snider High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this role, he’s responsible for the year-round athletic development of all student-athletes. Coach Roberts’ main responsibilities are teaching strength training classes during the school day, leading after-school training sessions, and running the summer strength and conditioning program. He holds a Master of Science in Kinesiology and is CSCS certified through the NSCA.