For me, working predominantly with an injured population essentially makes conventional compound loading sparse in most cases and imprudent in others. I’ve had to work extensively on how to program effectively for my athletes without overtaxing injured areas. When you work with injured athletes, you’re forced to see things from a different angle—because there are so many hard barriers, you’re prompted to engineer unique solutions that accommodate the athlete’s limitations.

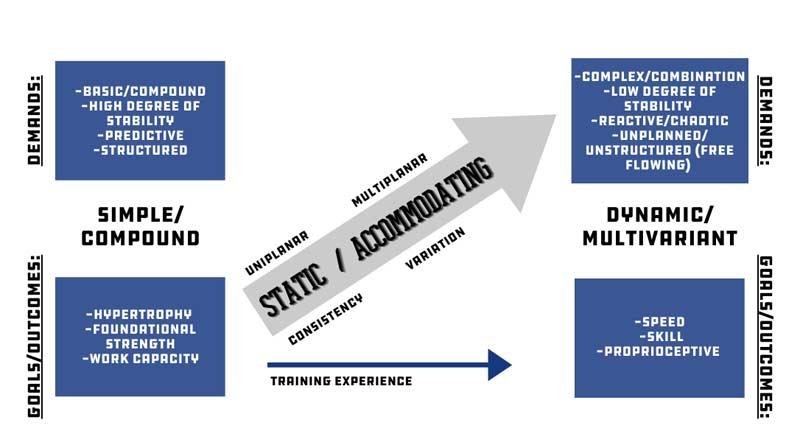

Having to do this so many times based on necessity has inspired me to develop a new paradigm for how I populate training hours, even with healthy athletes. You’re also forced into learning (and respecting) the significance of soft tissues. The ligaments, tendons, fascia, and joint capsules are unmistakably critical for overall health and function. While these tissues certainly need to be exposed to heavy static load, there is a strong argument to be made that most of the training effort should emphasize distal speed, terminal stability, and tissue quality as the athlete becomes more advanced. This has been a difficult, delicate balance I’m still figuring out.

The strength and conditioning field is an interesting space, to put it one way. In the same breath, S&C can be described as a “dog eat dog” world but also very much a copycat industry—there are a handful of predominant coaches/organizations that seem to set the path for the rest of us to follow. Along the way, some cling desperately to the industry leaders and take every word as gospel; in other cases, outcasts and radical thinkers take fundamental concepts and add their own twist or nuance to it, believing in their own mind they are revolutionaries of our field.

In fairness to both ends of the spectrum, I believe most coaches are genuinely well-intentioned, and we’re all really just trying to do one thing: figure out how to optimize human performance. But it goes without saying that for every one or two practical, beneficial, nuanced applications, there are hundreds of others that aren’t worth a damn—and remember, there is almost nothing “new” at this stage of the game. As we’d expect, this has continued to result in a great deal of debate, fervor, and borderline contempt from those across the aisles.

I was indoctrinated into this field by the likes of Louie Simmons, Eric Cressey, Mike Boyle, and others who are categorically “weight-centric” coaches. Al Vermeil, Dan Pfaff, and Buddy Morris are icons, in my view, and were instrumental in my early development as well. I can’t overstate enough that, to this day, I 100% love jacking some steel. When I put my personal bias for lifting weights aside, however, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for me to justify the practicality and effectiveness of conventional static weight for a lot of athletes and populations.

It’s becoming increasingly difficult for me to justify the practicality and effectiveness of conventional static weight for a lot of athletes and populations, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XWhich leads me to the premise of this article: Have we become overly reliant on using static loading with our athletes?

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9181]

Origins of Strength & Conditioning

First, a quick interjection. Allow me to take you back to 1968, about three decades before I was even born. The Nebraska Cornhuskers, who had ascended to become one of the powerhouse football programs in the country, were coming off a brutal 47-0 beatdown at the hands of Oklahoma in the National Championship. In response to this, Hall of Fame Coach Tom Osborne sought out Boyd Epley to pioneer the first concerted strength and conditioning program in the country. Asserting that his team was physically manhandled and underconditioned in their game against Oklahoma, Osborne was convinced that Epley would be able to push the Cornhuskers to a new level of performance by way of strength training, organized conditioning, and stretching.

As it turned out, Osborne was right.

Fast forward nearly a decade (1978), and Epley—who is largely considered the godfather of modern S&C—became the catalyst for organizing the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). To this day, it remains the American gold standard of our industry.

Around the same time, legendary bodybuilders like Arnold, Frank Zane, and others were radically popularizing formalized strength training. New magazines were circulating throughout the country at rapid rates; in essence, they made lifting weights cool and sexy. Then, in the 1980s, Arthur Jones introduced the world to the innovative Nautilus machine, which exploded from coast to coast, as commercial gyms were on a mercurial rise. Fast forward another decade or two, and little by little, the strength and conditioning industry became a mainstay in professional and collegiate sports, growing and evolving into what we know it as today.

And to this day, what we see in our field is still a direct extension of the work of these founding fathers.

Where Static Load Works

While I’ve become more reserved over the years as to who I feel is a good candidate for conventional static loading, please don’t misconstrue what’s in this article as me bashing weight training for athletes altogether. In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better strategy for developing fundamental strength or power than with a barbell. With young athletes, the predominant necessity is simple—get stronger, add some mass, increase confidence. So, it would stand to reason that static load and conventional patterns (bench/squat/dead) should be a staple in programming.

Along similar lines—although this one is more contentious among coaches—I feel the best way to develop foundational power with young athletes is, again, with a barbell and set of plates. Teaching athletes the clean, jerk, and snatch at a young age can pay huge dividends in the long run, even if the Oly lifts aren’t a mainstay in their training development.

Teaching athletes the clean, jerk, and snatch at a young age can pay huge dividends in the long run, even if the Oly lifts aren’t a mainstay in their training development, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XThe reason static load works so well here is a combination of factors:

- Point blank—it’s effective. Outside of sprinting and heavy plyos, static loading is unequivocally the most effective way we’ve discovered to apply a significant external force in a reasonably safe manner. It’s foolish to challenge the science on this, as we’ve overwhelmingly seen that lifting weights promotes a plethora of beneficial adaptations for developing athletes.

- The relative simplicity to coach and learn the big three and, for most, variations of the Oly lifts can be included here as well. The time it takes to teach them is time well invested. There are so many movements that stem from these, so beyond the lifts themselves, it’s critical the athlete is strong in these patterns and can perform them well.

The other situation where I believe static load is the best option is for muscle isolation, which applies largely to athletes in late-stage rehab or for athletes in need of localized hypertrophy/strength. Static loading promotes very little rep-to-rep deviation and, when coached and applied correctly, can be highly specific to localized regions. The lack of variability makes this a better option (in most cases) for localized strength/hypertrophy because the athlete doesn’t need to think about managing the path of motion. I would also add there’s generally an inherent familiarity to static loading, so the athlete can concentrate just on the work output without having to overthink it.

So, Where Is Static Load Overused?

And here’s where the feathers may start getting ruffled…

I think there are a few main applications where static load is not as effective as we like to believe and where I’ve found it to be suboptimal.

The first is with accessory lifts, in which coaches commonly include exercises like barbell or dumbbell RDLs, presses, bent rows, traditional lunges/step-ups, etc. Outside of young/developmental athletes, I think that these rudimentary movements have a very low return for athletes, mostly because the movements lack any degree of meaningful challenge or complexity and often don’t apply load significantly enough to drive a true adaptation. In a lot of cases with accessory work like this, it predisposes the athlete to just go through the motions—they’ve already done their meaningful work in the primary blocks, and now it’s time to go on autopilot and round the hour out.

Sure, I get that the adherence to training is a derivative of coaching influence, but even with strong coaching this can still occur. I believe, instead, there is a greater return on utilizing more variation and less structure with advanced and tenured athletes.

I believe there is a greater return on utilizing more variation and less structure with advanced and tenured athletes, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XThe more constraints we put on them in task-based exercises, the less time they spend moving how they naturally would. Athletes continuously manipulate their bodies (to create favorable leverage) and pressure distribution across the foot (to shift momentum) when accommodating and expressing force. This is where I feel static load and task constraints shortchange us on training return.

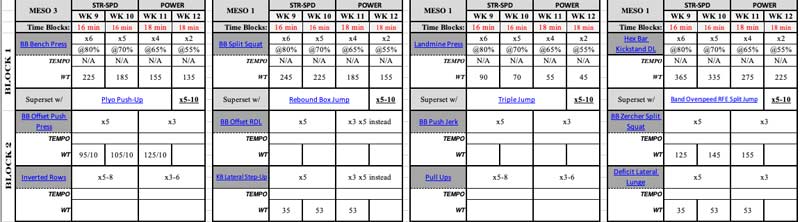

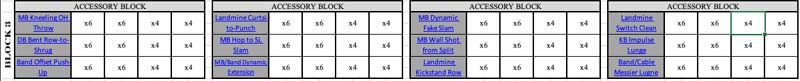

Thus, I emphasize multiplanar, multi-tempo movements that emphasize speed, position, and proprioception. And this is all achieved using a wide array of load applications. With where I’m at now, I keep the compound static loads mostly to the primary block, then work to more fascia-driven accessories in my subsequent blocks. Here’s an example of how I would write a typical mesocycle (power phase shown).

Notice the primary block is where I retain the conventional movements, but after that, I normally want to look for other areas to emphasize and apply different load or stimulus. Then, the tertiary block progresses even more toward being fascia-driven:

When athletes are no longer in a developmental stage (16-24 years old), the goal is simply to keep them healthy so they can go out and do what they do. Another way of perceiving this is “maintaining the strengths while developing the weaknesses.” As such, we want to apply load and movement selections that challenge the nervous system and proprioception, and again refine the confidence and feel of the athlete.

We need to be mindful of the fact that our goal is to have them best prepared for movements/speeds/vectors found in sport, not become the best at lifting weights. Not to mention, for athletes who’ve put 10, 15, 20 years into training, it can sometimes be more mentally than physically taxing for them to engage in training. A large part of our responsibility is to provide an atmosphere and plan that is invigorating and enriches the process.

Where We Can Do Better

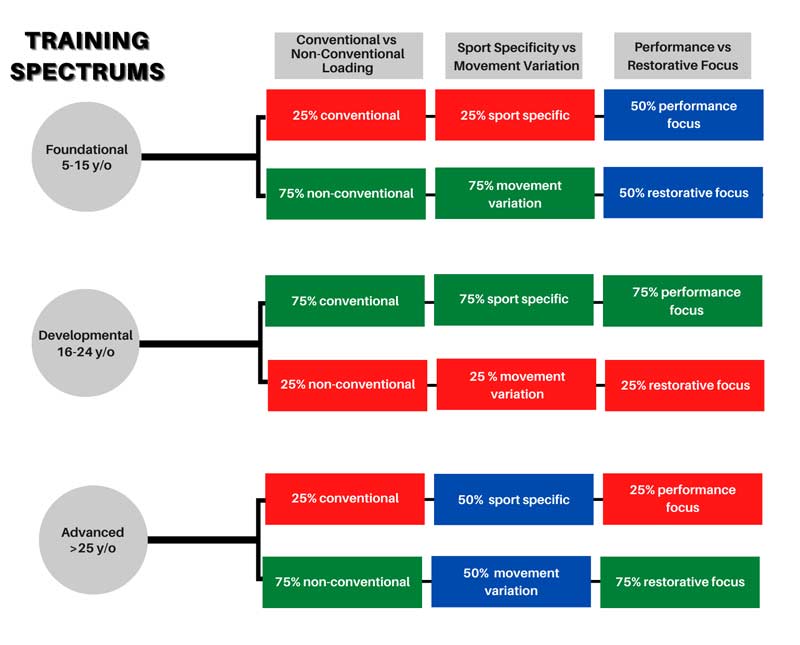

One of the overarching disconnects within our industry is recognizing the different spectrums of athlete development and the specific demands that should be applied for each. In the foundational stage (5-15 years old), athletes just need to have fun and understand the process of training. With this group, we can certainly sample some big lifts and have some semblance of structure, but I believe the most beneficial approach is organized chaos and exposing them to a bunch of movement variations that encourage the athletes to learn have fun.

One of the overarching disconnects within our industry is recognizing the different spectrums of athlete development and the specific demands that should be applied for each, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XDevelopmental athletes (16-24 years old) should absolutely be exposed to static conventional loading. These lifts should be peaked in some form or fashion throughout the developmental years and should be a predominant training emphasis. This is the stage where we are truly trying to peak the genetic potential and get after it.

Beyond those stages (>25 years old), I believe we should look more to non-conventional loading parameters in lieu of bludgeoning basic accessory movements for the sake of more weight: non-conventional meaning more predominant band loading, cable and landmine variations, and med ball/free flow types of movements. This is a group of individuals—athletes or otherwise—that in most cases have reached their genetic peaks. Therefore, we need to remind ourselves of the question how strong is strong enough?

For advanced athletes, joint taxation and overload should be a preliminary thought when programming. Athletes who have accumulated multiple injuries/surgeries over their career and are frequently battling chronic joint pain tend to have trouble executing movements under static load and constrained paths of motion. Dynamic resistance has shown to be optimal for muscular and soft tissue loading, while minimizing axial or compressive strain on the joint. In a sense, the dynamic resistance allows the athlete to manipulate their levers, giving them greater muscular advantage throughout the ROM.

Having worked extensively with injured athletes, I’ve found non-conventional training parameters and applications have largely been more effective than traditional static loading. Coordinating with athletes on how to achieve dynamic movements (e.g., bands, med balls, landmine), to find the optimal paths and ranges of motion, can not only give them a solution for loading but also help a great deal with their confidence.

For advanced athletes, joint taxation and overload should be a preliminary thought when programming, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XDynamic loading and variable movement patterns are generally more conducive to the types and expressions of force experienced in sport. The main variables we need to consider when discussing specificity or transferability are the nervous system and proprioception. Thus, by ditching the redundantly confined accessory movements, it opens more training time to work open chain and combination patterns that emphasize these systems while allowing the athlete to move in more compatible vectors. Once strength is obtained, it really doesn’t take much to maintain it, so as long as athletes don’t get fundamentally weaker, I can’t justify spending significant amounts of training time performing basic, redundant movements at moderate load.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11155]

The Road Ahead

All in all, I think the strength and conditioning industry is at a pivotal point in its evolution. Because of the rapid development of social media platforms, the feasibility of real-time data collection, and the continuous expansion of clinical research, we are starting to have a better understanding of what works and what doesn’t. But again, we’d be remiss to suggest that we have it all figured out and that what’s been done for decades is all that needs to be performed to optimize human potential.

You don’t need to just take this from me—there are several coaches who are far better than I will ever be who have also made similar statements recently. Industry legends such as Dan Pfaff, Stu McGill, and Bill Parisi have all been tremendous influences for me to break away from the trappings of conventional static loading. Dan has spoken on numerous occasions about the importance of recognizing the influences of hydrodynamics and the fascial system on human movement/performance (see recent podcast with Eric Cressey). In Bill’s groundbreaking book Fascia Training: A Whole-System Approach, he, Tom Myers, and Stu McGill share powerful stories and evidence that the fascia system has a much bigger influence on our function and performance than has been previously understood, which ultimately points to the conclusion that we have overemphasized structural lifting and conventional static loading.

I’m not here to sell you snake oil, but I would strongly encourage you to at least investigate some of this material. Specifically, I cannot recommend Fascia Training (Parisi) or Anatomy Trains (Tom Myers) highly enough; these books changed a lot for me. Along with keeping an open mind to perceiving the human anatomy through a slightly different lens, I would also encourage you to just sample different training modalities, variations, and load applications in your training. Instead of just concentrating on progressive overload with some of your tenured athletes, see how they respond to more multiplanar, open-ended movement patterns that challenge proprioception and movement fluidity.

Besides progressive overload with some of your tenured athletes, see how they respond to more multiplanar, open-ended movement patterns that change proprioception and movement fluidity. Share on XWe need to recognize when strong enough is strong enough and start to turn our focus toward making foundational strength more applicable for sport. Be cognizant of the fact that human performance is an amalgamation of multiple systems working in concert to produce gross, global outcomes. The muscular system is just one of many that must be addressed in training.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF