Some stereotypes are real. As a born and bred Parisian, I do not always carry a baguette under my arm (although I would if it weren’t for dietary concerns), nor do I own a beret. However, yes, I can’t start my day without a strong black coffee, and most of all, like many of my fellow Parisians, I love to debate.

In the strength and conditioning community, debating is second nature. How to increase strength, the ideal post-workout shakes, or which gradient is best for blood flow restriction—every subject seems to have its share of fiery, opinionated comments and ongoing investigations.

The warm-up, though, is not a sexy subject. Talking shop about your warm-up routine is a hard sell. Unlike strength, power, or speed, the warm-up is rarely attributed to the success of an athlete; and since it doesn’t involve rankings or records, it does little for egos.

Considering that an athlete’s training regimen ultimately plays a part in their success, the warm-up should be a main concern. Share on XHowever, considering that an athlete’s training regimen ultimately plays a part in their success, the warm-up should be a main concern. Indeed, no athlete trains strength or aerobic stamina every session, but every single training includes a warm-up. If you do the math, there is a high likelihood of your athlete spending more time warming up than developing any single particular physical quality over an entire season.

So, why not give the warm-up the debate it deserves?

Practice with a Purpose

In team sports, ask any player to describe the warm-up and the most common responses will likely be boring, routine, useless, and long. The main reasons for these perceptions are that—because of the warm-up’s constant occurrence day after day and its lack of recognition as a critical aspect of physical development—many of us give up on making this moment a learning experience for the player.

Instead, we default to what we feel comfortable with and what is easy in organizational terms. Out on the pitch? Let’s do running mechanics and pretend we don’t see that players just go through the motions in meaningless gesticulations. In the gym, we distribute foam rollers and massage balls because it’s better than nothing. We often give our players an implicit message whether we mean to or not: We tell them that the unique goal of the warm-up is to reduce injury risks through some sort of activation.

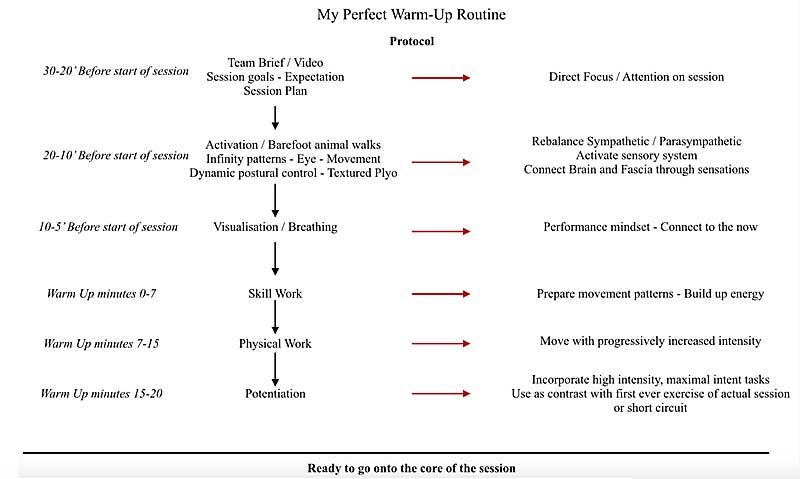

Warming up, in fact, has at least three main goals: pre-activation, mental and sensory preparation, and potentiation.

1. Pre-Activation: Preparing the Body

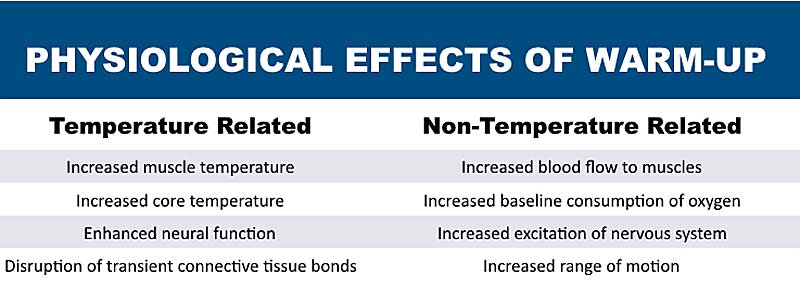

The first role of a warm-up is to prepare the body for the physical activity that will follow. Almost all studies on the warm-up are only concerned with that aspect. A well-designed warm-up can confer a number of physiological responses that could potentially increase subsequent performance. Those physiological responses can be categorized as:

- Temperature related

- Non-temperature related.

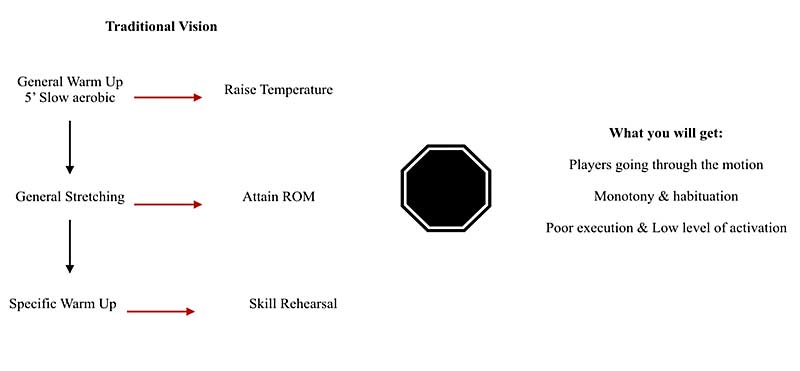

The narrow scope under which the warm-up has largely been studied resulted in practitioners designing warm-up routines aimed at three main purposes:

- Raising temperature (light sweat).

- Raising oxygen uptake (higher breathing rate).

- Increasing range of motion (open up articulations).

What would be guaranteed to easily hit those three targets? Some slow aerobic work topped up with a little bit of stretching…and that is how many warm-ups can still be described today.

The problems with such a simplistic approach to warm-ups are numerous. First, its low level of specificity to the sport and the particular type of session it is supposed to prepare the player for make it a poor strategy for positively impacting execution and/or motivation. Second, this type of warm-up routine is generally repetitive. Thus, players quickly reach a high level of habituation and instead of increasing their readiness to train, the stimulus actually does the reverse: monotony and boredom decrease neural activation.

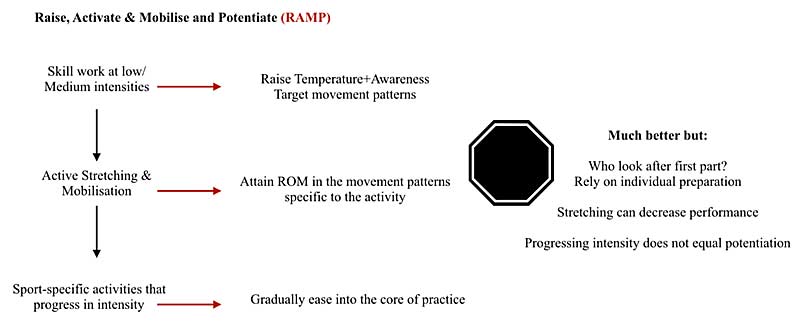

Some of those shortcomings are addressed by a much better protocol: Raise, Activate, Mobilize, and Potentiate (RAMP).This protocol, created by Ian Jeffreys, is composed of three phases:

- Raise – Activate: Increase muscle temperature, core temperature, blood flow, muscle elasticity, and neural activation.

- Mobilize: Focus on movement patterns that will be used during the activity.

- Potentiate: Gradually increase the stress on the body in preparation for the upcoming competition/session.

The RAMP protocol puts some emphasis on specificity, which is lacking in the more traditional approach. By focusing more on movement quality during the warm-up, the subsequent quality of the session may be raised—which, over time, can add up to significant improvement in performances. Here the focus is not on flexibility but on mobilization, or actively moving the body through the movement patterns and ranges of motion athletes will be required to master for their sport and for their performance capacities.

By focusing more on movement quality during the warm-up, the subsequent quality of the session may be raised—which, over time, can add up to significant improvement in performances. Share on X

Much better, yes, but not perfect. If the RAMP protocol seems to address the question of warm-up as activation convincingly, this isn’t the sole purpose of a warm-up.

2. Mental and Sensory Preparation (Get in the Zone)

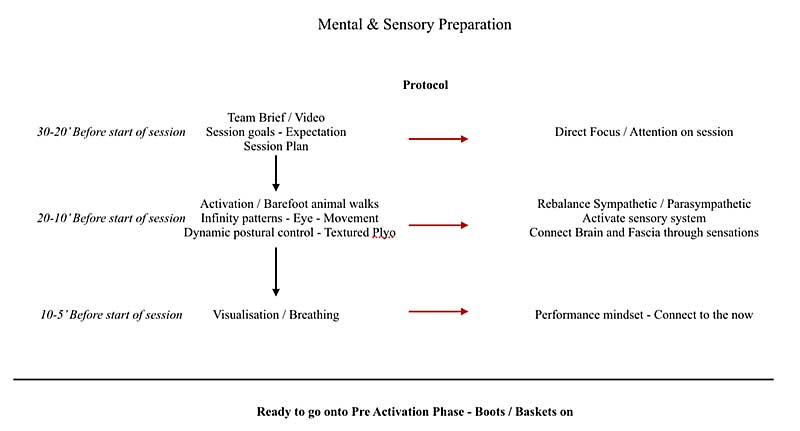

A well-designed warm-up should not just prepare bodies, it should get the player into a state of focus and receptive to learning experiences. In order to achieve such a state, it is fundamental that a warm-up protocol includes mental and sensory preparation.

In the 1960s, American neuroscientist Paul MacLean formulated the “triune brain” model, which is based on dividing the human brain into three distinct regions:

- Reptilian or primal brain (basal ganglia).

- Paleomammalian or emotional brain (limbic system).

- Neomammalian or rational brain (neocortex).

According to MacLean, the hierarchical organization of the human brain represents the progressive acquisition of brain structures through evolution. The triune brain model suggests that the central grey nucleus was acquired first (assumed to be responsible for our primary instincts), followed by the limbic system (responsible for our emotions or affective system), and then the neocortex (assumed to be responsible for rational thinking).

The reptilian brain is dedicated to survival, and to basic needs. Part of this primal brain is called the reticular activation system. The reticular activation system (RAS) participates in the fight-or-flight response. Recent findings on the nature of the activity generated by the RAS suggest that arousal is involved much more in perception and movement than previously thought. The reticular activation system is a cholinergic system, which means that its activation involves the production of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACH). Acetylcholine is used in muscle contraction and in the brain, where it helps regulate the central autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and plays an essential role in memory, attention, and motivation.

If you want to avoid repeating yourself countless times throughout the session—as well as avoid the numerous mistakes often made at the start of a session (that we attribute to concentration)—the secret is to start by activating the RAS. Activating the brain by stimulating the RAS is possible through the vestibular or visual system. For example, when we yawn, we essentially activate the ligaments of the tongue that are connected to the vestibular system. Yawning or pushing your tongue against the palate thus “wakes up the brain.”

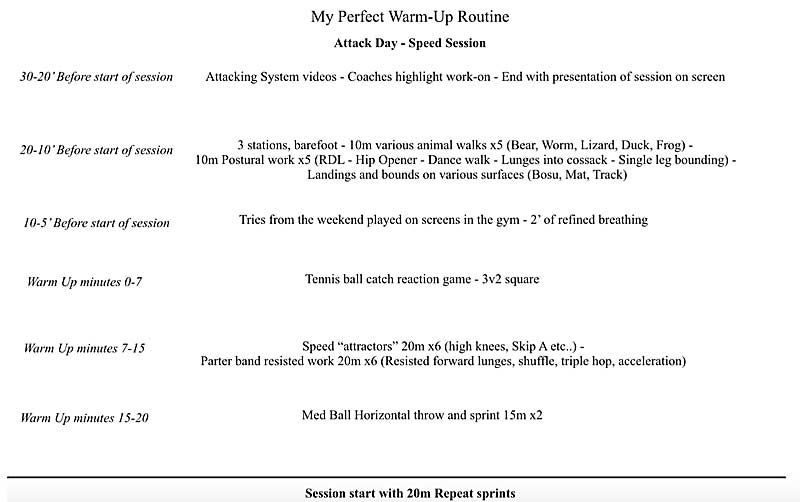

Getting your players to yawn during your warm-up probably won’t attract praise from the coaching staff, so another solution is to reproduce the infinity sign through infinity walks. Getting the player to walk, then run, then do running mechanics drills following a figure-eight pattern while keeping their eyes on a specified target is a great way to start a field session. Juggling while performing some easy movement (lunging, squatting) can be another option. Finally, playing some reaction games such as “shadow bowing” or “finger fencing” would do the job in an entertaining way.

Next comes the limbic system. Here again, an essential role in the movement should be emphasized. Responsible for emotions, this part of the brain determines the athlete’s state of mind and the resulting quality of movement. For the coach, being able to generate a state of motivation in the athlete is one of the critical aspects of the successful learning of complex motor tasks. Without an optimally functioning limbic system, all learning will be fleeting.

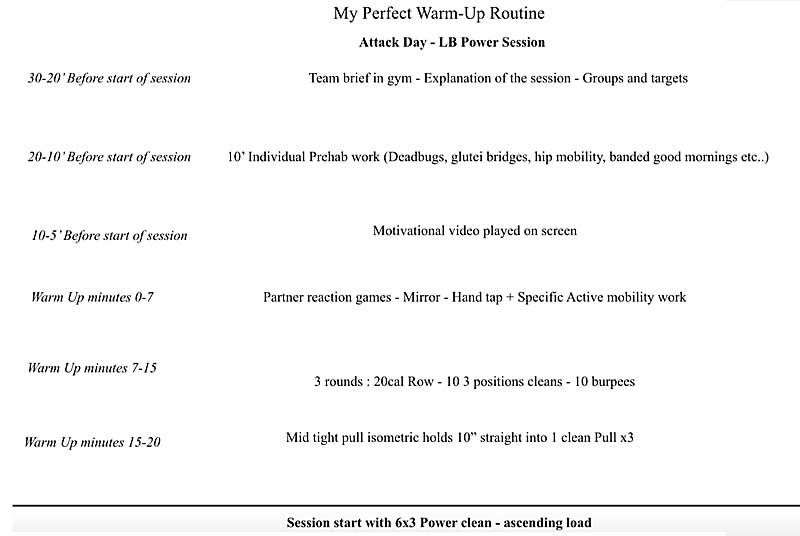

The corpus callosum, which connects the two cerebral hemispheres, is a key structure in activating the limbic system. The best way to ensure athletes are in the right state of mind—one where cortisol production is under control—is to include tasks in the athletes’ warm-up that require “crossing the center line.” Animal walks, bear crawls, and other crawling motor activities activate this region of the brain, connecting the two hemispheres, and should be a part of any warm-up routines.

Training sessions are learning experiences designed to make an athlete better. We know that in a state of “fight or flight” and under too much sympathetic activation, our learning abilities are reduced to a minimum. We know as well that being overly relaxed isn’t exactly the best way to get the most out of the training content. When players show up to a session, the state of their central nervous system influences how meaningful the practice will be to them.

The warm-up is the airlocked entrance separating the learning experience from the rest of the athlete’s day. Letting them carry over disappointment, anxiety, euphoria, or anger into the training session—all emotions that a team selection meeting can easily trigger, for instance—can largely annihilate any positive physical or technical adaptations. It is the duty of the warm-up protocol to include mental preparation tools aimed at refocusing players on the now and rebalancing parasympathetic and sympathetic systems.

It is the duty of the warm-up protocol to include mental preparation tools aimed at refocusing players on the now and rebalancing parasympathetic and sympathetic systems. Share on XIt is also paramount that the warm-up strategy activates the RAS and provides some sensory stimulation. Some may argue that this sensory activation is really where injury reduction takes place. Often, non-contact injuries result at least partly from a discrepancy between mechanoreceptors expectations in terms of the amount of vibrations about to enter a muscle or joint and the actual amount of vibration (this goes beyond the scope of this article); simple sensory stimulation can help fine-tune the receptors to the environment.

Before trapping the vast number of precious mechanoreceptors present in the foot in a tight boot, thus reducing to a minimum the quantity of information received through vibration, it is a good idea to get the player to spend some time barefoot. The information fed back to the brain by the feet is critical to the optimal execution of movements such as running, jumping, landing, changing direction, and kicking.

The tight shoes used in most sports make it hard for the feet to capture quality information; however, it is possible to “prime” those mechanoreceptors beforehand, making them more receptive to vibration changes. A few simple plyometrics drill such as single leg hops, landings, and bounds on three to four different textures, from hard to soft (box, grass, mat, sand, for instance) would ensure the players’ feet are fully activated and ready to contribute to the quality of further movements.

3. Physical Potentiation (Revving up the Engine)

How the warm-up ends is another critical aspect that is easy to overlook. How does a warm-up protocol that finishes with five minutes of stretching carry over and impact a high-intensity running session? How can another set of A-skips assist the player to smoothly transition to a tactical session?

After preparing the body, the mind, and the sensory system, a good warm-up should directly contribute to the success of the following session by nimbly bridging the gap between activation stimulus and the session’s targeted outcome. Ultimately, a well-designed warm-up should make the remainder of the practice seems easier.

Ultimately, a well-designed warm-up should make the remainder of the practice seem easier. Share on XWhen the warm-up precedes a strength, power, or speed session, the physiological effects of potentiation can be used. Potentiation results from the phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chains that enhance the actin and myosin function of the muscle. To achieve a potentiation effect, the exercises that conclude a warm-up protocol should drive the neuromuscular performance from an overflow of the H-reflex, thus increasing the athlete’s performance.

The potentiation effect can be elicited through three main methods:

- Ballistic

- Plyometrics

- Tension overload

The ballistic method uses light load and focuses on the maximal acceleration phase of an object’s movement while limiting deceleration. Commonly, this is achieved through the use of various medicine ball throws. From experience, it works very well as part of a circuit to finish off the warm-up before an upper body strength or power session.

The plyometrics method uses jumps, hops, and bounds, where the focus is placed on rate of force development or the maximum amount of forces in short time intervals. It is great to use as a contrast with the exercise it aims to potentiate in a power or strength session. For example, take a lower body power session where the main lift is a power clean, and the rep/set scheme is 6×2 @ 85% of 1RM. Before the first attempt, including four sets built up (2 @ 50%, 2 @ 60%, 2 @ 70%, 2 @ 80%) interspersed with three hurdle jumps or high box jumps can do the trick.

The tension overload method focuses on maximal tension, where the goal is to fire up the central nervous system before performing an explosive movement. The best way to achieve this stimulus is through the use of heavy isometrics. Like the plyometrics method, tension overload works really well as a contrast.

Properly chosen potentiation exercises have been shown by numerous studies to increase performance in the subsequent exercise performed. If your gym session starts with a main lift, or if you are out on the pitch about to work on accelerations, using such a tool to get more out of your athlete is a no-brainer. Among the reported benefits of a potentiation strategy are increased power, increased arousal, and lower perceived fatigue. However, benefitting fully from the potentiation effect isn’t just a simple addition. Studies report highly individual responses as well as possible excessive additional fatigue (especially in less trained athletes).

The timing is another very important aspect of the success of a potentiation strategy. Indeed, you may have the perfect exercise combination in mind, but if your head coach likes getting his speech done after your warm-up, this is going to be a problem. Logistics are another limiting factor: the best possible potentiation exercise choices may not be realistic. Olympic weightlifting may work best to spark up your athletes before a power-orientated session on the field but taking barbells and plates onto the pitch would give the head groundskeeper a heart attack and damage the training field. When on the road, it is also often the case that access to equipment is restricted. Finding medicine balls to get a potentiation circuit done can be quite tricky.

When the training session is aimed at aerobic development or is a long, highly specific tactical session, performances could be increased by including breathing exercises at the end of the warm-up.

Nasal breathing cleans the air as it enters the body, produces nitric oxide (NO), and while utilizing nasal breathing, the same amount of work can be performed at a lower energetic cost. The release of NO helps control blood flow by diffusing to the underlying smooth muscle cells. The strong vasodilatory effects of NO lead to increased oxygen uptake, reduced pulmonary vascular resistance, and arterial oxygenation.

The benefits of increased NO productivity include increased aerobic capacity, reduced hypertension, improved insulin sensitivity, and glucose tolerance. Also note the existence of a positive effect on capillarization and angiogenesis. An added benefit of NO is that it increases neurogenesis, the process by which new neurons are formed in the brain. These physiological conditions can positively influence the performance of an athlete. More studies are needed to fully validate its use as a true potentiation strategy, but nasal breathing could well be a potent tool to add to your warm-up protocols.

More studies are needed to fully validate its use as a true potentiation strategy, but nasal breathing could well be a potent tool to add to your warm-up protocols. Share on XPutting It All Back Together

A good warm-up does not go unnoticed, and an indifferent one is a real missed opportunity to get more out of each and every session. Before diving into the core of a learning experience—whether to elicit a physical, technical, or tactical improvement—not only does the body need to be adequately prepared, but the sensory system does as well. Mental preparation is equally necessary to ensure athletes are fully engaged and train with purpose. Finally, when it is deemed appropriate, the warm-up can serve as a ramp, propelling a player’s performance through the use of potentiation or breathing exercises.

An easy way to ensure we take full advantage of a warm-up protocol is by making sure it connects athletes to the now, to the environment, and finally to the specific stimulus of the training session.

Maybe you think that a full hour of preparation before getting to the beginning of a session is unrealistic, or that the protocol proposed is a nice philosophical piece but unlikely to be transferable to the reality of day-to-day operations. I hope I can change your mind with a couple of practical examples.

An easy way to ensure we take full advantage of a warm-up protocol is by making sure it connects athletes to the now, to the environment, and finally to the specific stimulus of the training session. Share on XAfter using this protocol for a few weeks, some observations I have made:

- Objectively, the number of technical errors (dropped balls and kick negatives) recorded at training seemed to decrease, though more data is needed before assuming any statistical significance.

- Subjectively, the players enjoyed the process and reported feeling more energized and powerful during practice.

It hasn’t been an entirely smooth ride, however, and the first few times the extensive protocol received criticism from both players (the “in and out” mentality being strongly voiced) and coaches, who struggled to accept the additional lag between the meeting or video session and practice.

As a happy medium, I use this protocol only before the first session of the day where sensory and mental preparation is the most needed, and now no one wants to go back to the old way!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF