[mashshare]

One thing every coach of every sport knows is that they love speed. I don’t know how many times in my sport coaching career I have heard: “You can’t teach speed!” In my humble opinion, that’s most definitely a gray area. I would suggest that you can increase speed by increasing the efficiency of your athletes. Speed is a skill, and you can certainly teach a skill to be improved and more efficient, leading to the growth of that skill.

I went into the field of sports performance from a football background. As many of my colleagues with a similar background can attest, “speed” is an abstract in many ways. We understand that “speed kills.” We love having fast players. We grasp the concept that running fast will make you faster. However, for those of us with a weightlifting background, speed often takes a back seat in the educational process.

Sets, reps, exercises…. Do we use Olympic lifts, back squats, unilateral versus bilateral? What can we do in the weight room to improve speed? These discussions often dominate the scene. Coaches spend countless hours teaching their athletes the details of every weight room movement they program.

Often, though, when it comes to the speed training side of their program, coaches find a “canned” program on the internet or get a .pdf or PowerPoint from another coach, buy a stopwatch or a timing system, and off they go. There is no doubt that running fast is an integral part of any speed program.

Are we, as coaches, getting too far down the road of “just run fast” and maybe leaving the most important training modalities out of our programs? Can we explain the “why” of each and every drill we do, or are we just copying things we have seen or done before? Is every detail of our speed program well-thought-out and reasoned, or are we just having our athletes run as fast as possible and hoping it makes them better because Twitter said it would? Am I timing my athletes just to collect data, or is it actionable and giving me information I can use to make them better?

These were the questions I began asking myself when looking at how we program for speed. When I took a hard look at it, I came to the conclusion that we were doing a lot of running fast, timing just to time, and drills just to drill. We had to figure out a better process.

“Fast” is something we all desire in our athletes. Our solution? Get smarter, train smarter, and TEACH our athletes speed. Combining “fast” with intelligence, technique, and the same attention to detail most of you already use in your weight room programming can take your team speed to a new level.

Combining “fast” with intelligence, technique, and the same attention to detail you use in your weight room programming can take your team speed to a new level, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XYou would never just set a steak dinner in front of a child and say “eat up” without showing them how to use a knife and fork. That would be inefficient, indeed. Why would we think that simply lining up our athletes and timing them running as fast as they naturally can would be any more efficient?

Yes, feed those cats some speed. Just make sure you have a solid plan to TEACH them to eat in the most efficient way possible. This article will discuss our ongoing educational process at York Comprehensive High School and discuss the how and why of going above and beyond the feeding process.

Chasing Numbers vs. Recording Progress

A very popular sports performance topic on social media is “chasing numbers.” The idea is to say, “I want our players to squat X amount” or “run a 4.6 forty,” and then build a program that has a primary focus of reaching those goals. As I mentioned in a previous article, I got my start writing for SimpliFaster after a long Twitter debate I had on that very topic. I’ve written before that I believe there is a gray area that coaches need to bring into focus when they discuss “chasing numbers.” The fact is we ALL chase numbers. We want stronger, faster, more powerful athletes. The real debate needs to be about our process for selecting and pursuing those improvements.

Every coach reading this has stories about the sport coach who declared that, once a certain percentage of his team could bench 300 pounds, they would win more games. Replace bench with squat, clean, or deadlift, and put any number in place of 300, and we have all heard it over and over. As qualified sports performance professionals, we understand the flaws of that mindset. However, we all also have proven and evidence-based protocols to force the adaptations we desire within our athletes in the weight room. We ARE chasing those adaptations (that are measured in number form) on a daily basis. The difference is how we go about that chase. We understand “why” we do things and how those specific things will help our athletes improve.

Jumping from strength programming to speed programming often results in a loss of those philosophies. If you wouldn’t do a 1 rep max on the back squat with a freshman athlete until a point in their development showed a mastery of squat technique, why would you line up that same athlete once a week and laser time them in a sprint without the same attention to detail? Yet, I’m quite sure that’s what happens in many places.

You know as well as I do that there are coaches out there who buy a timing system to see how fast their athletes are and feed them with “speed,” but neglect to teach the athletes mechanical efficiency. Those coaches have numbers—probably some pretty good ones. What amount of “food” are they leaving on the dinner table by not teaching those athletes “how to eat”? Timing our athletes without teaching them the most efficient way to move is “chasing numbers” in an inefficient manner. Yes, they probably will get faster by just running faster.

By refocusing on efficiency and trading some of the time you spend sprinting and timing for teaching, I contend you will see greater improvements in the long run, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe human body has an immeasurable ability to adapt to stimulus. Is making that number a little bit better enough? I contend we should find ways to maximize those abilities in our athletes. Of course I do, so do you! Are you willing to take a real and candid look at your program? Can you answer the “why” question for every part of your speed program? By refocusing on efficiency and sacrificing some of the time you spend sprinting and timing to trade it for teaching time, I contend you will see greater improvements in the long run, and your cats will eat even better!

Our Process – More Than Sprint and Hope

The process that led us to take a deeper look into the way we design our speed program had a direct relationship to our strength program. In other articles, I’ve gone into detail about how we level our athletes and use a process of teaching and “slow cooking” our athletes in the weight room. We believe in the blocking system, to the point where I often have to spend time explaining to frustrated coaches and athletes why we don’t rush the back squat or an Olympic lift. I dwell over every detail to make sure our protocol is what’s best for our athletes.

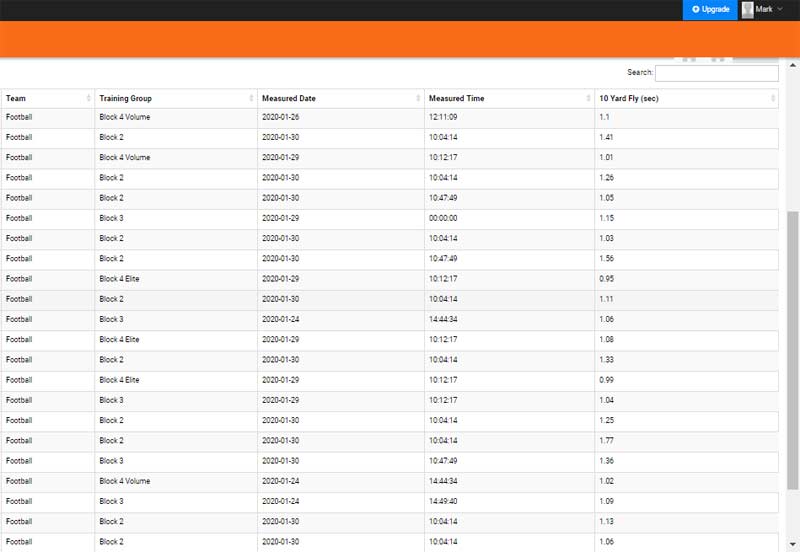

We laid out every aspect of our strength program for our athletes in detail, from middle school through graduation. Then, when we went outside to the track, we lined them up and they all did the same drills, they all ran the same sprints, they all did the same tempo running, etc. We ran flying 10’s timed with our Dashr system twice a week. I did very little with that data other than post the five best times on social media with the hashtag #FeedThe Cougars. We were leaving a lot on the table uneaten.

I began to ask why our strength program was so detailed and individualized, but our speed program was so “canned”? How could we take the ideas and philosophies we lived by in the weight room and use them in our speed program? We have signs with the wording of the messages we preach: MOVE WELL, MOVE FAST, MOVE STRONG, and the most important sign:

The order of importance for athletic development:

- Technique/Movement

- Volume

- Load

We had been using that formula backward. It was time for a better way of training, so we would reap better results.

It was at that point that I remembered I was still a football coach. Maybe I have not coached the sport in a few years, but deep down inside, I will always be a football coach. I was lucky enough to have coached at quite a few places over the years where we were pretty much at an athletic disadvantage week in and week out. You may wonder about my word choice of “lucky”? And I didn’t look at it that way always, either. Upon reflection, it couldn’t have been a better reality to develop in as a coach.

It’s easy to coach great athletes. Not to take anything away from those that do so, but that’s just a fact. All I’m saying is your margin for error is exponentially linked to the level of athlete you coach. If your team is loaded with D1-caliber players, does it really matter what offensive or defensive system you run? Humans by nature will adapt to their surroundings. If the small details don’t really make a difference between wins and losses because you have three NFL players on your team, there is a good chance those details get overlooked.

On the other hand, if you are outmanned most weeks, you’d better figure out an insane attention to detail very quickly. EVERYTHING you teach matters in being competitive. You also end up with one heck of a “coach’s eye.”

When I began looking at how we could overhaul our speed program, I went back to my roots as a football coach who would watch that first step of every rep in practice on video over and over. Share on XIf the first step isn’t right, we do not move to the second step. That thought process carried over even as my path changed. When I began looking at how we would overhaul our speed program, I went back to my roots as the football coach who would watch that first step of every rep in practice on video over and over. The coach who made his assistants explain why they did every drill in practice, and how it would transfer to Friday night. The coach that prided himself as a “teacher of sport,” not just a coach.

Chasing the ‘Why’ to Solve Your Puzzle

Step 1 in my process is chasing knowledge. I heard a great quote (unattributed) not long ago: “People fail on the margins of their knowledge.” This is a process I have become very familiar with over the years. What lies past the “margins” of your knowledge and how you push into those areas is your individual puzzle. Solving that puzzle is a daily routine for me and has been for many years.

I tell people all the time that my “superpower” isn’t innovation, per se. It’s having an intense desire to learn WHY people who are highly successful at something are so successful at it. What tools or exercises, etc., do they use and WHY do they use those in a specific situation, instead of just watching a video and attempting to copy what looks good? Knowing the “why” and not just the “how” allows me to take the general aspects of the great things each of these people do and innovate them into best practices for improving the athletes I work with.

I first did this as a football coach, learning the intricate details of the “why” of each of the most successful double wing offense coaches in the country. I then developed a highly successful version of my own and tweaked it to fit the athletes we worked with. Next came the foundation of my knowledge of the weight room and jumping programs. Again, I’ve spent my life seeking out coaches to build relationships with in order to learn the “why” of the art of sports performance.

This started with Ethan Reeve, who sparked my fire for this profession and continues to do so until this very day. I’ve never once used the exact same program, and I never will. I won’t ever jump from “program to program” because I believe in evidence-based principles that will never change. However, I am in a constant search for ways to tweak and adjust what we do and how we do it to move our athletes forward.

Sprinting was always something I believed in. Until I made it a priority to blow past those margins and be able to have my own “why?”, I never realized the impact I could make on our athletes. Most of us are not world-class sprint coaches and won’t ever be. Still, you should seek out those who are and learn! Seek to gain an understanding of WHY these coaches do what they do. Once you have that level of comprehension, you can then begin to build your program.

Every program is different. You need to be able to individualize what you do for your athletes, not parrot others in a different situation. I have read and listened to every word that coaches like Chris Korfist, Boo Schexnayder, Cal Dietz, Scott Salwasser, and Matt Gifford have said, and I have reached out to many others. This has allowed me to formulate our unique way of programming.

Social media isn’t where you get the knowledge you need. It’s too shallow. Many high school coaches follow well-known “speed” coaches on social media. They watch these coaches’ posts and the drills they do, and they say, “Hey, that looks cool. Let’s do that.” Trust me, I was one of them. The problem is most times we are seeing the best version of the best athlete that coach has.

A friend of mine called this “strength and conditioning porn.” Sprinting, jumping, lifting—whatever it is. Most of the time what we see isn’t reality; as he put it, it’s “pure fantasy.”

We have to get deeper into WHY the coach is specifically doing that drill and see if that is even applicable to the athletes we train. In episode 80 of the “Just Fly Podcast,” Cal Dietz discusses how he reached out to a world-class speed coach about issues his athletes at the University of Minnesota were having. The sprint coach had to really think about how to help because he had never, ever seen most of those issues with the level of athlete he worked with. Many of the coaches we follow on social media will not have the same experience as you and your athletes.

Make yourself a great teacher of speed by first being a great student of it. Network, read, study, and get a handle on the most basic fundamentals of speed, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XMy point is, don’t compare and try to make your athletes into world-class sprinters by doing world-class sprinter drills. Make yourself a great teacher of speed by first being a great student of it. Network, read, study, and get a handle on the most basic fundamentals of speed. Then expand your base from there, until you have your own philosophy. Remember what I said earlier about coaching that first step? Master it, program it, teach it, and then coach it before lining your athletes up in sprinting groups, firing up the Dashr system, and saying, “Anytime after the beep…Go!”

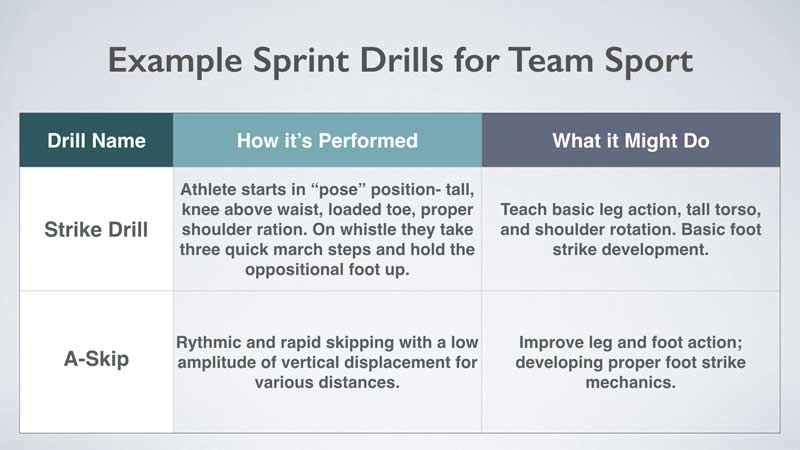

Drills, Drills, and More Drills

Once you have the knowledge you need to teach what your athletes need, begin building drills that have direct correlation to those techniques. Don’t fall into the trap of “speed porn” when deciding what drills you will use. Be a teacher. If you teach fourth grade math, you don’t spend time on the AP Calculus curriculum because you watched a cool video of a lesson. You add to the base of knowledge a fourth-grade student will need to advance to fifth grade.

Additionally, don’t fall into the “go, go, go” trap. That can be a battle, especially for a sport coach or a strength coach with a sport-heavy background. One of those lessons I learned from coaching lower levels of athletes was to not get obsessed with constant full-speed tempo. Who cares how efficient and fast your practice looks if your teaching and learning process isn’t effective?

Not every rep has to be full speed during the teaching phase. The lifeblood of relative advantage is mental toughness, and mental toughness comes from confidence in your ability to perform what’s asked of you above anything else. Yes, the ultimate goal is to work to a point where athletes run faster than they did before. Is it really best practice to do something full speed using poor technique?

As a football coach, I would never jump into a full-speed “team” session without talking it, chalking it, walking it, jogging it, and drilling the techniques for each position. Why? Because we won’t get much better doing it that way. Why would you do drills for speed development any differently? Streamline the drills you do, choosing quality and transfer over quantity and aesthetics. Don’t program anything without asking and answering “why”? It will help keep you grounded in the basics, and mastering the ordinary, everyday aspects of what you do will always be a more effective route.

Back in my football days, we had a go-to play that we worked year-round to master. We ran it 70% of the time in many games. When we tried to “get cute” or go away from that play, it backfired more often than not. It was at that point I had one of our assistant coaches stand next to me, and every time I called anything other than “superpower,” I had him ask me why. If I didn’t have a good answer quickly, we ran superpower. It was our “ordinary,” and it rarely failed us because of our level of mastery of it. Design your drills with THAT type of process in mind.

A big part of us being able to use submaximal speeds to teach and build proficiency in our speed development program was the use of rate of perceived exertion, or RPE. This was a natural step that flowed very easily because of our use of RPE, as well as extensive use of APRE (autoregulated progressive resistance exercises), in our strength program.

Although it’s quite prevalent among coaches to say, “Okay, let’s run this one at 50%” or “75%,” etc., I kind of see that in the same light as a doctor writing an athlete a note to me saying “don’t lift heavy.” Unless you define “heavy,” there is a zero percent chance the athlete (or the coach, for that matter) will be able to quantify that into a real weight. The same goes for giving athletes a percentage. Most of them have no idea how 50% will feel compared to 75%. They will guess, and it most likely won’t vary a whole heck of a lot.

To remedy that, we correlate speed RPE to what we use in our strength program. Ten is hair-on-fire full speed, 1–2 is walking, and so on. So, when we give them a tempo speed, we will say “RPE of 6–7” if we want them in that 60–70% range. We practice this and let them feel each range. It’s not the perfect way of doing it, but until we can acquire some real-time heart rate monitors, it at least gets us in the ballpark. We use the same system for drills and warm-ups. You need to find a range that maximizes your athlete’s skill acquisition for each phase of your programming.

I’ve found that, for us, 4–5 building to 6–7 is a sweet spot in the general preparation phase of our early off-season. Our goal is to reach a level of proficiency where we can be in that 8–9 range most of the time, while dipping into that 10 a few times per session in our final phase. I once heard a coach say that sprinting at 90–95% will maximize the athlete’s ability to master technique. Going over that speed will actually cause them to lose efficiency.

I once heard a coach say that sprinting at 90–95% will maximize an athlete’s ability to master technique. Based on experience, I agree, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XWhile I can’t source that study, I can tell you from our experience that is exactly what we see. We do this with the idea of improving skill as we advance toward the part of the off-season where the athlete’s energy system must be prepared for the rigors of what can be a regular dose of 8–10 in the higher volumes that come from sport practices.

Dartfish and Video Keep Us Honest

The next step in the process was figuring out how to make sure the drills we focused on were effective. We need to be sure we are progressing before we begin adding speed. Once again, I leaned on my football experience. Using video of practice sessions became invaluable as a football coach, and it has now become invaluable to us in our speed program (and other areas) as well.

We try to record as much as we possibly can in our speed development program. I’ve found that the biggest advantage of using this tool is it keeps me honest. One thing I’ve always said is that action on the video is never as bad or as good as it can seem live. Watching the movement of your athletes and having a mental or physical checklist of what you are looking for in each session is a huge advantage. Video has become a tool that drives our programming.

Some battles we’ve had with our kids involve shoulder rotation, how they hold their hands (no fists), hand level, and not crossing the body. Video analysis has become a huge factor in helping our athletes improve in these areas. If we can see it over and over, we can cue them in drills individually. We can also actually show the athlete, and that is worth 100 reps.

Another area that video has helped is the start. We want an athlete to be a jet, not a helicopter. I read that a while back, and it has become a huge cue for us. Just as a sport coach uses video as a teaching tool, so do we. Most of our sports teams utilize the Hudl system. I have access to that as well and can easily upload and share any footage with athletes or coaches. I do caution sending those out to less-experienced athletes, however. I’ve found it best to watch with the athlete until they have a grasp of what we are teaching and why.

Record as much as you can, and not just when you are timing. You want to see as much video of your athletes in an “organic” setting as possible, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XRecord as much as you can, and not just when you are timing. You want to see as much video of your athletes in an “organic” setting as possible. If you video once in a while, the athletes will perform for the camera. If it’s part of the daily process, chances are you will see the movement in a more natural form, allowing you to coach it.

Timing and Speed Training – Realities of Workflow

From reading this article, you might have assumed I’m not a fan of timing our athletes on a regular basis. Or maybe I’m not a fan of running fast to get faster. The fact is those assumptions couldn’t be further from the truth.

I love fast, I love timing, and I love timing our athletes when they move with technical proficiency. I’m also a fan of developing a year-round speed development plan that will maximize our athlete’s abilities on the field. I’m a fan of improving efficiency by teaching technique and mastering correct basic movement patterns. I’m a BIG fan of teaching our athletes to move in a way that will allow them to move at max speed with the lowest possible risk of injury. Doing all of these things will allow us to progress the athlete to a point where video will give us actionable information on when we should start timing our athletes at max speeds.

The combination of the timing and feedback also allows us to get the RPE number of the point at which our athlete’s efficiency breaks down. If we have an athlete who can really move well in that 6–7 range but loses it above that, we need to time them at that 6–7 range while coaching them to run their best time possible without breaking down. They will improve as they push themselves more and more. Soon enough, they will be at an 8 with better technique and moving faster than they would have at a high level with less skill development.

That’s a TOUGH sell to athletes and sport coaches. We have to emphasize that “slow cooking” process they have become familiar with in the weight room. We all know intent goes up when the timing system or stopwatch goes on. Running at full speed with bad technique is not the most direct path to maximizing speed. Besides, what’s the hurry? In the weight room, you understand that you will hopefully be the most powerful version of yourself during your competition phase, not in the first off-season phase of training. Why would speed development be any different?

I love the sprinting groups. I love the excitement and energy that is in the air when the athletes see me walking out with what we call the “Nuclear Codes Case” that holds our Dashr timing system. I love the level of competitiveness those things bring out in our athletes.

The technology of sports performance gets better by the day. I love that fact as well! In fact, I absolutely embrace that. You certainly don’t have to have technology in your program to be successful, but in my experience, it is a huge help, and it makes your life as a strength coach that much easier. Just the area of data tracking and record-keeping for your speed program is life-changing!

I used to be an Excel guy. I’d print a sheet and hand it to the kids. I carried a clipboard and wrote down number after number. Then I sat down in front of my computer and painstakingly typed in that data. From a sprinting standpoint alone, think about the old hand-timed and clipboard way of doing it. Could you hand-time multiple times a week and enter that data? I couldn’t, that’s for sure.

The future is here, and if you can possibly do so, embrace it. I’m so excited by what the future holds for us as sports performance professionals. As just one example, Dashr has produced a radio frequency identification (RFID) module that uses wristbands worn by the athlete to full automate the timing process. With the Dashr wristband, each athlete has an individual barcode that they scan into the system, get set, and go. When they break the laser at the finish, the data uploads to a single spot. When you need it, you print it.

Need historical data? There’s no need to flip through sheets on a clipboard or search an Excel document. You’ll go from pencil, paper, a hard time with a +/- 0.5 of a second “thumb” error, and multiple coaches needed, to a fully automated system that tracks, uploads, and stores all the data. The future is bright, and it’s welcoming in any and all growth-minded coaches.

Our Athletes Are the Bottom Line

As you can see, I love the pursuit of knowledge and the journey toward mastery of the art of sports performance (that will never end). You can also see that I love technology and all the possibilities that are out there for coaches today. What I love most is doing what will help our athletes become the best version of themselves on the field. To do that, we need to use the exact same principles we use in the weight room, the classroom, and/or on the field/court in our speed development program.

To help athletes become the best version of themselves on the field, use the exact same principles you use in the weight room, classroom, and/or the court, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XYes, let’s run fast to get fast. Let’s do that through a process of teaching the concept of speed and speed technique. Knowledge, teaching ability, and principled speed concepts combined with intelligence and technology will allow you to turn your “cats” into precise and focused hunters who will be able to maximize their natural abilities to be the fastest animal they can possibly be.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]