Back when I taught forensics, I used to tell my students that they needed to understand their opponent’s argument just as well—if not better—than their own. In the sports realm, an ongoing issue coaches continue to debate is strength training as it relates to both sprinters and distance runners. As you’ve perhaps noticed, most coaches have strong opinions on the subject.

Although health issues caused my unanticipated retirement from coaching, I still enjoy being part of the discourse and sharing views with colleagues from around the country, as well as the current members of the Lisle High School coaching staff. In this post, I’ll present the strength training argument from different perspectives.

There is no Holy Grail of #StrengthForSpeed. The perfect training, like a perfect cup of coffee, is always going to be subjective, says @Zoom1Ken. Share on XIn this regard, I’ve covered two positions on this issue. Neither of these sides actually represents my current thinking on the debate, but they do highlight that there is no Holy Grail of strength for speed. The perfect training, like a perfect cup of coffee, is always going to be subjective.

Barry Ross, Allyson Felix, and Breakthrough Training

I began my pursuit of strength training for speed in the 1970s with exercises performed on a Universal machine—that’s all the school owned, and they wanted coaches to use it to justify the expense. Later, I experimented with Olympic lifts a few years after Valeriy Borzov’s success in the 100m and 200m dashes in 1972. I paid a lot of attention to the outstanding translations of Russian research, thanks to the efforts of the great Dr. Michael Yessis, for whom we all owe a debt of gratitude for translating such an important body of research. After that stretch, I went through a period of no lifting, believing that some of the fastest sprinters at the time, like Carl Lewis, didn’t follow any strength training protocols. My next run at the high office of elite sprint coaching involved no lifting but lots of jump training and plyometrics.

That changed in 2004 when Barry Ross—a high school throws coach and renowned garage lifter from the 1960s—contacted me about a strength program he had been using at LA Baptist with the legendary sprinter Allyson Felix. That approach, which involved heavy deadlifting, was based on his interpretation of the seminal research on ground support forces conducted by Dr. Peter Weyand at Harvard University. Many criticized Ross’s method, which he highlighted in his book, Underground Secrets to Faster Running: Breakthrough Training for Breakaway Running.

Part of the interest he generated, as well as some of the criticism, was because of his link to a genuinely elite young sprinter, Allyson Felix. Some wondered if the Holy Grail he claimed to have found was not a specific strength training program but simply Felix herself—a rare talent who would have performed brilliantly under any coaching regimen.

Though it seems Barry capitalized on the performances of such a gifted athlete, the reality—as he points out in his book—was that Felix approached him, saying “I want to lift weight with you.” Felix made that decision after returning from a US Junior National Championships event where, even though she was just a high school freshman, testing revealed that she already ranked at the elite levels in almost every category—except her strength, where she was below the minimal rating scale.

Rather than relying on the established “garage routines” he had learned from the great George Wood and Dave Davis, Ross carefully studied the seminal works of Dr. Peter Weyand and Leena Paavolainen. Weyand’s research introduced him to the concept of mass-specific force, and Paavolainen’s study pointed out that reduced contact times were a significant factor in faster running speeds.

The Barry Project: Applying the Ross Method with High School Runners

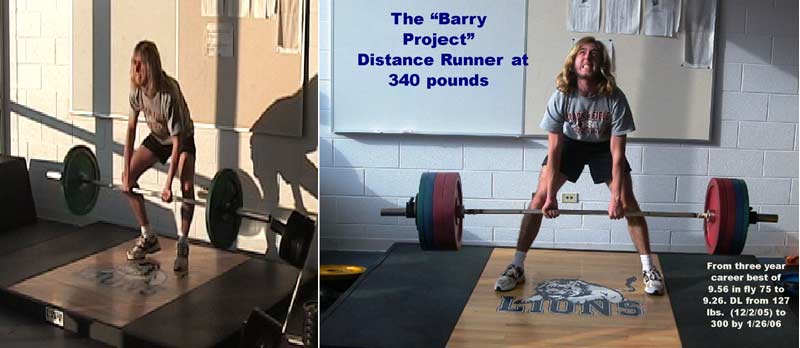

During my numerous and lengthy conversations with Barry Ross—via a phone my family referred to as the Barry Hot Line—I proposed a challenge: I would train a single subject, a fairly successful distance runner (10:03 two-miler), who had never touched a weight his first three years of high school. The challenge required that I follow Ross’s procedures to the letter and send him video clips of the athlete’s progress. The results were quite astonishing. The runner, who struggled to deadlift slightly more than his body weight (119 lbs.) in the first two sessions was pulling 300 just seven weeks later and maxing for the season at 340.

The plyometrics routines also showed dramatic improvement, to the point that, on a fairly warm day in January (a 50-degree day in Illinois being an oddity), we went to the track to test his fly-in speed over 75 meters. He improved from a career-best of 9.56 to 9.26. That spring, while suffering from a pulmonary infection, he struggled in both the 3,200 and 1,600, but in the 800, he went from a best of 2:18 to 2:08. For the first time in his prep career, he ran the opening leg of our state-qualifying 4x800m relay.

That performance was certainly impressive, but when we later adopted the program with our entire team, I began to wonder if his dramatic improvements could have been achieved without any specific protocol simply because he had no prior strength training experience. Dramatic gains in novices are not that unusual. Nevertheless, I stayed with the Ross protocol because all our athletes had impressive strength gains and enjoyed trying to make Ross’s deadlifting Hall of Fame by pulling 2.5 x body weight. I had to send Ross images of my athletes at different points of their qualifying lift to validate that the lift was indeed authentic and not just staged, a requirement that further excited team members.

Debate—A Regulated Discussion Between Two Matched Sides

Some of the things below you’ll agree with; others you won’t for good reasons. The title of this post, “The Politics of Strength Training for Speed,” refers to something Senator Eugene McCarthy once said about politics being a lot like football: “You have to be smart enough to understand the game,” he said, “but dumb enough to think it’s important.”

My version is slightly different. Strength training for speed is indeed a lot like politics: You have to be smart enough to understand the best approaches by which strength training can improve speed, but dumb enough to think coaches will all agree on the best way to achieve this end.

I’ll begin with two insights, one that addresses Weyand’s contribution to Barry’s thinking, and the other that highlights why Paavolainen’s insights made sense to him. Dan Cleather noted the following: “Many of the capabilities that people train for (e.g., acceleration, velocity, agility, power) are just variations of a person’s ability to express force.” According to Cleather, it’s critically important to remember that the capacity that determines the ultimate performance within a skill is the ability to express force.

Dutch coach Frans Bosch has very strong opinions on strength training for speed. Because he believes that distance runners are just sprinters with bad coordination, his insights reflect that endurance runners should take strength training seriously for their events as well. “When highly trained endurance athletes reach a ceiling in their oxygen uptake,” Bosch said, “greater mileage will not improve it.” He believes the best way to further increase V02 max is through maximal strength training.

So, here’s my point and counterpoint on strength training. While these do not reflect my current views, I present them as viable arguments.

The Argument for the Ross Protocol: Should the Future Look Different than the Past?

Should the future look different from the past? I recently raised this question—and the next question below—after considering how contemporary views on strength training are moving away from the reductionist thinking that seemed so attractive to me years back.

If I were coaching for another five years or more—understanding that the focus is moving toward co-contraction and velocity based training—would I change my approach (deadlifting protocol) to accommodate a growing body of evidence corroborating the efficacy of taking into account the coordination of muscles groups as well as the speed of movement?

My conclusion: I would continue with the deadlift as we have in the past. The Ross protocol I used with my high school athletes accomplished what Ross believed is critical for strength to have an impact on speed:

- Athletes need to produce superior strength with minimal mass. According to Ross, athletes who can deliver additional ground force of 1/10thof their body weight would realize an increase in maximum speed of one full meter per second.

- The strength training program takes into account the appropriate regeneration of the phosphagen pool; athletes have to recover to sustain intensity.

- The lifts should engage multiple joints and muscles.

- High school athletes have varying degrees of skill and, to achieve the mechanical adaptations necessary for faster sprinting, they need to sprint. The program should be efficient as well as effective in getting the athletes running fast on the track.

- For our situation, the program required minimal equipment and reduced preparation downtime. We were able to deadlift right on the track during good weather and in my classroom on inclement weather days. Like a traveling circus, we could set up and take down quickly.

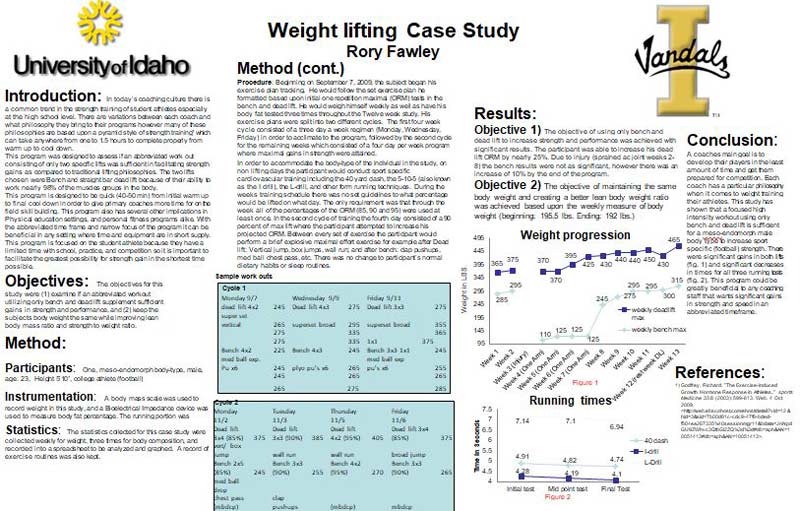

In terms of results, our athletes got stronger without getting bigger; Ross believed that the disadvantage of added mass was a greater gravitational pull. As Dr. Mike Young often notes, “fat don’t fly.” If the goal is to generate and transmit muscular force to the ground, and if increased forces result in greater speed, our results were similar to those Rory Fawley found with his University of Idaho athletes (see Image 4 below).

A focused, high-intensity workout using just the bench press and the deadlift resulted in significant gains in strength and significant increases in speed. He concluded that “this program could be greatly beneficial to any coaching staff that wants significant gains in strength and speed in an abbreviated time frame.”

Ross believed that his training method for increasing mass-specific force “should be preferred until it is proven wrong, while every aspect of training that is irrelevant should be removed.” His formula for success is indeed attractive in its simplicity:

- Base all sets and reps on 1RM’s, staying at or above 90% and 100% as often as possible.

- Randomly select between intense days and high volume days.

- Keep pushing to establish a new max when you can easily do three reps of your current max.

Many coaches who struggle to add more aspects of contemporary training into their programs appreciate the simplicity of a strength protocol like this. For the level of athletes my colleagues and I coach, the actual training ages of these athletes, and the results they achieve in terms of moving metal—and moving faster—Ross’s breakaway training can result in breakaway running. As the great Russian strength coach Pavel Tsatsouline might say, it’s a program that is “simple and sinister.”

The Counter-Argument on the Ross Protocol: Although the Ross Method Initially Improves Some Aspects of the Rate of Force Development, Is This, In Fact, the Best Approach?

I’ve made the argument for continuing the Ross protocol, but here is a very powerful argument as to why a reductionist approach in terms of strength for speed might not produce similar results as athletes increase their training age.

In fact, there are good reasons for considering that heavy strength training might limit the potential for speed improvement, and the early successes can mask long-range problems. As Mel Siff used to say, “Any idiot can train another idiot for the first year successfully.”

Although strength gains in an exercise do occur as a result of conventional heavy lifting, these gains don’t transfer from the exercise to sprinting movements. In other words, we need to focus on what the muscles are actually doing while our athletes are trying to sprint faster.

Research shows that the hip extensors (gluteus maximus, adductor magnus, and hamstrings) and the hip flexors (iliopsoas and rectus femoris) are the most significant contributors to lower body power. Since this is the case, we should concentrate on what happens during a sprint’s swing phase. Knee extensors (quadriceps) and knee flexors (hamstrings) contribute most to lower body power during the swing phase, and ankle plantar flexors (soleus and gastrocnemius) contribute most to lower body power in the stance phase.

Despite beliefs to the contrary, what happens in the stance phase is not associated with running speed. So, if we want to run faster, hip extensor and flexor power, and knee extensor and flexor power need to increase.

The best way to improve the ability of the hip extensors and flexors to generate power in the swing phase is to use high-velocity exercises, like jump squats with light loads and kettlebell swings (for the hip extensors). Over the past several years, I’ve moved to more kettle activity and trap bar jump squats.

The best way to improve the ability of the knee extensors and flexors to absorb power in the swing phase of the sprint is to use eccentric training that involves activities like reverse Nordic curls (for the knee extensors) and either Nordic curls or lying leg curls with eccentric overload (for the knee flexors).

With this in mind, here’s my conclusion for this side of the debate:

Heavy strength training is not the best way to produce the adaptations that contribute efficiently to force production for faster sprinting. It can work—and it appears to work well—with beginners and athletes with lower training ages. The argument I raised years ago about the neural adaptations I believed were taking place can be just as easily attained by high-velocity or eccentric training. High-velocity strength training for the hip extensors and flexors, combined with eccentric training for the knee extensors and flexors, may be a superior approach.

And that’s why I was excited about Bar Sensei for analyzing the lifting velocities. Though the simplicity of the Ross protocol for improving sprint speed remains popular, I’m not convinced it improves intramuscular coordination. And we know that even the slightest drops in intramuscular coordination can result in a huge drop-off in performance.

The most effective methods for training muscle groups used in sprinting may be those that target key muscles in the way that they will perform during high speed sprinting.

Closing Arguments

I hope these points reinforce that strength training is a lot like politics in that coaches—like candidates—have strong opinions on the best ways to help athletes achieve faster times in their events. But according to Bosch, strength is not an independent phenomenon. “The strongest athletes are by no means the fastest,” he said, “and evaluation of training always shows that, in technically complex sports, increasing force production does not automatically lead to improved performance.”

Coaches will continue to confront the negative relationship between overload and specificity, says @Zoom1Ken. #StrengthForSpeed. Share on XBosch once described conventional strength training as a “dead-end street.” Though seemingly controversial, he was pointing out that coaches will continue to confront the barriers presented by the negative relationship between overload and specificity. This central and peripheral model poses challenges. Strength activities that target the movements of sprinting—the central approach—are more specific, but difficult to overload. And strength activities that focus on overload—the peripheral approach—are not as specific to sprinting but are easily loaded. It’s like a teeter-totter.

The coaching conundrum is that exercises that achieve significant overload but are less specific, and exercises that are very specific but provide little overload, are “pointless.” And this leads Bosch to remind us, “There are no holy grails in training.” As a result, the choices we make in terms of strength training are often a cup better to keep passing on, knowing that we’ll never resolve the arguments either way.

I will conclude with one of my favorite insights from Mel Siff: “Science is not perfect; practice is not perfect; but together they have a greater chance of going a great deal further than separately!”

I believe the same applies to coaches. Our approaches and concepts may not be perfect, but by sharing our ideas without completely dismissing divergent points of view, we can accomplish more for our athletes than we would by working separately. I’d like to believe that, though none of us can lay claim to having found the Holy Grail of strength training, we’ll find some common ground, and, in the spirit of collegiality, “take a cup of kindness yet.”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Additional References

Bosch, Frans. Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach. 2010.

Cleather, Dan. The Little Black Book of Training Wisdom: How to Train to Improve at Any Sport. 2018.

Great Article Coach, a question though about high speed work for hip flexors, what in particular have you found to train the hip flexors fast or explosively?

Great article coach! The two sides to the argument seem to lead me to a conclusive answer regarding training approach as it relates to training age (TA). Wouldn’t it make sense to focus on building overall force production while athletes are early in their TA then progress to VBT as they have expressed ability to generate high force outputs later in TA?