Strength and conditioning coaches are always on a crusade for the holy grail, and like the myth, it is impossible to find. Like most innovation, it starts with a problem that needs to be considered with a different thought process to find answers. Strength and conditioning coaches seek to prepare athletes for the demands of the game so that they can be robust and resilient and perform at higher levels than before. Although this mythical program that can be deemed “the greatest” in athletic development doesn’t necessarily exist for everyone’s circumstances, S&C coaches are getting closer to solving their inherent problems with preparing athletes for the demands of the game.

Football is played five months out of the year, which leads to a huge chunk of time spent working on general abilities in the off-season. There’s a notion that strength and conditioning work removed from sports training for half the year hinders the growth of the athlete and lessens the transfer of newfound abilities into game play. You don’t win games by having the strongest team; you win games by having the most skilled team. Players will have to abandon the ladder or four-cone box drill, and the question the S&C has to ask is whether they are ready for the completely reactive environment associated with field sports.

Unlike many field and court sports, football out of season traditionally has less skill development—specifically in the area of small-sided games and agility training methods. In this series of articles, I will introduce progressions and drills that aim at attacking the training void between general training and specific training as it pertains to American football.

Agility and small-sided games are two crucial components of sports training. Agility refers to the ability to change direction quickly and efficiently in response to the environment, while small-sided games are modified versions of traditional sports that involve fewer players and smaller playing areas. Incorporating both training concepts into an off-season program will decrease the shock that accompanies the chaos of play and lessen the chance of injury.

Small-Sided Games: The Game Teaches the Game

The sport of football has been using small-sided games for years to help develop specific skills of the game, and by football, I mean soccer. Small-sided games reduce the number of players or field size from normal game play, and American football uses SSG in practice with inside run, 7-on-7, and even tackling drills. The use of SSG does not have to end once the season is over—in the off-season, it is critical to continue the skill development that accompanies SSG exposure. Using reduced field space in evasion/tracking drills will allow players to focus on position and get them valuable reps in a scenario that occurs frequently in game play. We will go through the progression in a later article, but readers should know that it does not require a complicated process of drill progressions:

- Find a piece of the game that is common.

- Reduce the players to focus the attention of the active participants.

- Close down the field space to allow the players to work on specific skills.

By removing variables, players can really dial in on the specific techniques of the situation.

Video 1. Small-sided and reaction games in football training.

The Injury Issue

One of the greatest threats to the success of a team is injury. Injuries are an unfortunate part of the game, and there is no true way to completely prevent them outside of simply not playing. The S&C coach has to problem-solve injury trends and provide training that addresses the major issues accompanying the sport. While the term “injury prevention” is a fallacy, I truly do believe injury mitigation can be accomplished with the right training environment. Too often, we see a focus on general training leading up to the competitive season without the inclusion of full-speed, reactionary drills (SSG) and wonder why athletes get hurt in the first few practices of training camp.

Reaction and positioning go hand in hand, so to not bridge the gap between general and specific training is setting the athlete up for failure, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XReaction and positioning go hand in hand, so to not bridge the gap between general and specific training is setting the athlete up for failure. In the research paper “Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies,” the authors stated “Control over the dynamic restraints, independent of the motor control level, can be considered to occur both in preparation and in response to external events. Preparatory actions occur on the identification of the beginning of an impending event or stimulus as well as its effects, whereas reactions occur in direct response to sensory detection of effects from the arrival of the event or stimuli.” This is where the importance of SSG in preparation for specific conditioning plays such a pivotal role in the mitigation of non-contact injuries.

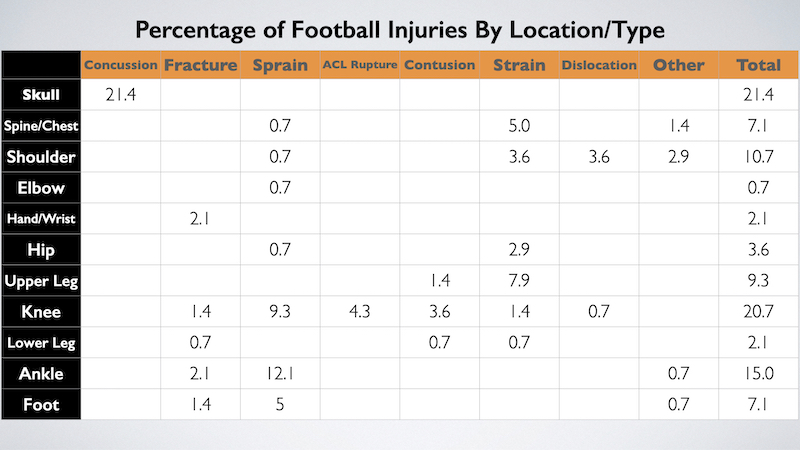

Figure 1. A comparison of injuries in American collegiate football and club rugby. S&C coaches can get on the right path to mitigation by providing training modalities that address these problems. Data adapted from: Comparison of Injuries in American Collegiate Football and Club Rugby (sagepub.com)

Several other researchers have also spoken on this subject, pointing toward incorporating specific modalities like SSG in training. A study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that athletes who participated in small-sided games had better sprint performance and agility than those who did not. Another study published in the Journal of Sports Sciences found that small-sided games were more effective at improving aerobic fitness than traditional training methods.

Strength and conditioning coaches are trying to find a way to develop the energy systems in a specific way to increase capacity for the demands of the sport, which would lead to fewer injuries. Less fatigue present in continuous game play will lead to less chance of injuries, and research has shown that SSG can provide that better than traditional conditioning due to the locomotion demands and rest/work ratios. Furthermore, a study published in 2014 found that small-sided games were associated with a lower risk of injury than full-sided games. When athletes train in similar environments to game play, they are prepared for the demands of the game.

Components of Agility

General skills make up the foundation of great agility alongside increased peripheral vision and faster reaction times (OODA loop). Acceleration, deceleration, COD, and max velocity are the underlying attributes that help determine success in the open environment of play. With deficiencies in any of these areas, the chances of being elite diminish. It’s the price of admission, so to speak, because if you lack the general athleticism to keep up with the more athletically endowed players, reaction times can only make up so much ground. A skill is how well someone can perform a task; in the chaotic realm of sport, the task in football comes down to two simplified themes: to create space or close space depending on whether the player is on offense or defense.

If you are an offensive player, you are trying to create space; the counterpart to that is if you are on defense, you are trying to close space. The beauty of football is that offensive players can be defensive in plays, like an offensive lineman in a pass set.

The four general skills stated above allow this to happen more rapidly. Zatsiorsky stated, “an increase in sports performance, the time of motion decreased.” This is multifactorial and should demand the attention of the strength and conditioning coach to allocate time to building the general locomotion skills necessary to move faster while concurrently exposing athletes to reactive environments in a planned and progressive manner. It’s like learning how to say the alphabet before embarking on the journey of writing an essay—you want to make sure that you can spell the words properly and write the correct letters.

In a profession that preaches “slow cooking” athletes, we are too often quick to say that in the developmental stages, we should just let the athletes figure it out in play versus giving them clues first on how to figure out the complex task of faster game play. What’s wrong with an emphasis on both?

Videos 2 and 3. Speed and agility development in training.

Deceleration

One of the main catalysts for injury is not having the coordination or capacity to stop movement. S&C coaches train and prepare athletes for the demands of the sport while improving the underlying factors affecting faster sports motion. Deceleration, in particular, is the underpinning factor in greater change of direction and max velocity speeds, which are directly responsible for creating and closing space but also prevention of non-contact injuries.

Video 4. Training deceleration on the football field.

Dr. Damian Harper defines deceleration as: “[The] ability to proficiently reduce whole-body momentum, within the constraints, and in accordance with specific objectives of the task, while attenuating and distributing the forces associated with braking.”

Deceleration ability may be the biggest determining factor in performance when looking at general skills and their effect on sports, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XDeceleration ability may be the biggest determining factor in performance when looking at general skills and their effect on sports. In the research article “Change of Direction Tasks: Does the Eccentric Muscle Contraction Really Matter?,” Helmi Chaabene stated, “From a practical observation, suggest that coaches should consider implementing eccentric strengthening, which is the main muscle contraction regime activated during deceleration, in their training program directed at promoting COD outcome.” Not training or preparing for the high-intensity deceleration events in sport can lead to compensation mechanics or severe injury.

COD and the Four Main Pillars

Change of direction and agility are not the same! You can change direction without a stimulus, whereas agility is a change of direction brought on by an environmental cue. COD is one of the biggest determining factors in faster game play—the only sport that doesn’t have COD is track. A 10.5 time in the 100m is only useful on the football field if you can navigate defenders.

Increasing acceleration and max velocity output is extremely important but is not the end of the rainbow. The gold is getting these general skills to transfer to specific skills like tracking, closing, and evading, which have more components than just running fast. Change of direction is directly affected by another general skill: deceleration. As previously stated, what’s the point in speeding something up if we cannot slow it down? A skill gets better with rehearsal, so while increasing the contributing factors to speed, COD, and deceleration, strength and conditioning coaches also need to reinforce the biomechanical positions that are associated with advantageous change of direction movements.

When you break down the tape of game play, four distinctive change of direction movements stand out:

- 180-degree cut

- 90-degree cut

- 45-degree cut

- Maneuverability

These movements show up over and over again. In many situations, they change together. When you avoid training these positions, you remove the bridge between speed and game speed. Training these components of COD is learning the alphabet. It’s the old metaphor of learning to crawl before you run.

When you avoid training change of direction positions, you remove the bridge between speed and game speed, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on X

Videos 5 & 6. Training angled cuts and maneuverability.

OODA Loop

Game speed and OODA loops are two concepts that are important in sports training and competition. Game speed refers to an athlete’s ability to perform at the same speed and intensity as they would in a game or competition. This involves not only physical speed but also mental quickness and decision-making ability. When I see people train in closed drills or general skills the entire off-season without the presence of open reactive environments, my mind always goes to the Mike Tyson quote, “Everyone has a plan till they get hit.” Peripheral vision and pattern recognition are two of the main drivers of fast reaction times and increased OODA loop processing.

The OODA loop is a decision-making process coined by military strategist John Boyd. It stands for:

- Observe

- Orient

- Decide

- Act

In sports, athletes must constantly cycle through this process to make quick and effective decisions on the field. They must observe the situation, orient themselves to the environment and the actions of their opponents and teammates, decide on a course of action, and then act on that decision. Increased game speed hinges upon the ability to cycle through this loop and use the appropriate strategies from a movement standpoint. We have all coached that one kid who was fast as hell in testing, but for whatever reason, the game moved too fast for him, and he played slower than his capabilities. An athlete’s inability to discern the environment from potential threats slows down the “decide” and “act” portions of the loop, leading to what a lot of coaches have termed “paralysis by analysis.”

Coaches can incorporate the OODA loop into sports training by focusing on decision-making skills and situational awareness. You can create drills and exercises that require athletes to quickly observe and react to changing situations, forcing them to cycle rapidly through the OODA loop. Game speed training can include drills and exercises that simulate game situations and force athletes to react quickly and make split-second decisions.

These critical pieces of training—game speed and the OODA loop—are important concepts in creating a transfer from general skills to specific skills. Athletes who can perform at game speed and quickly cycle through the OODA loop are more likely to be successful on the field. It’s not the fastest athlete who wins; it’s the athlete who plays the fastest. Coaches and athletes should incorporate these concepts into their training and practice routines to improve their performance and decision-making abilities.

It’s not the fastest athlete who wins; it’s the athlete who plays the fastest, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XThe OODA loop can also be linked to injury rates in sports. In high-speed and high-impact sports, such as football, athletes constantly make split-second decisions that can have a significant impact on their safety. Therefore, having a well-developed OODA loop is crucial for athletes to avoid injuries.

The OODA loop helps athletes quickly observe and orient themselves to their surroundings, make informed decisions, and act on those decisions with precision and control. By cycling through the OODA loop rapidly, athletes can make split-second decisions that can help them avoid collisions, adjust their movements to avoid injury, or protect themselves. Game speed and the OODA loop can also help athletes develop their adaptability and flexibility.

The game of football is chaos, and no play is identical. Having the ability to react to an ever-changing environment will give players a competitive advantage and protect them from bad positions that could lead to the risk of injury. By incorporating these concepts into training and practice routines, athletes can develop their decision-making abilities, mental toughness, resilience, and adaptability, all of which can contribute to their success on the field.

Having the ability to react to an ever-changing environment will give players a competitive advantage and protect them from bad positions that could lead to the risk of injury, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XIn the next three articles, I will touch upon:

- How GPS can help create specific thresholds and guide planning for SSG and agility to match practice stressors.

- How to progress from closed COD drills and advance them into open reactive environments.

- How to incorporate and plan these sessions into the training week.

Every coach wants faster game speed and a decreased chance of injury, and small-sided games can deliver. SSG and agility training, when paired with general skills and capacities training, can produce a robust athlete that is able to handle any situation with accuracy and precision.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF