You’ve probably never heard of John Boyd, but there is a good chance that you’ve heard of his most famous creation: the OODA loop. Boyd, who died in 1997, was a United States Air Force Fighter Pilot who became a consultant to the Pentagon before retiring and moving into his own form of academia. Boyd has been highly influential on military strategy across a number of projects—his early work led to the development of the F-15 “Eagle,” F-16 “Fighting Falcon,” and F-18 “Hornet” fighter planes, all of which are still in use today. Following the completion of these projects, Boyd turned to an overall strategic approach and developed his OODA loop, a viewpoint which set the basis for US military strategy in the first Gulf War and which is still in use today.

In Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, author Robert Coram presents Boyd’s biography. In a time of so much information enabling us to shortcut our thinking practices—often not beneficially—never before have we needed a role model like Boyd: someone who could think so differently from everyone else that it led to extreme innovation, effective outcomes, and strategies that are powerful today.

We needed a role model like Boyd: someone who could think so differently from everyone else that it led to extreme innovation, effective outcomes, and strategies that are powerful today, says @craig100m. Share on XThe picture Coram paints is that Boyd was not an easy character to get on with; he had no respect for authority and was more than willing to be difficult to get what he wanted. He was so fixated on his life’s work that, after retiring from the Air Force in 1975, instead of getting a well-paid job as consultant or defense contractor, he instead decided to reduce his needs to zero, so that he could fully focus on developing his theories. This, on the surface, is admirable—but when you have a wife and five children to support, it’s perhaps a very selfish decision to make. Boyd’s children still largely resent his decision to this day.

I highly recommend you read Coram’s book in full, but I want to pull out some key points from Boyd’s story which we might be able to use to better prepare athletes to perform. I’m going to do this through the lens of middle-distance running, which is unusual for me—but I think it’s an area in which Boyd’s concepts can be highly applicable.

Energy-Maneuverability Theory

The first major innovation Boyd produced is termed the Energy-Maneuverability Theory. Boyd was a fighter pilot, accustomed to being involved in air-to-air combat against an enemy. In the mid-1950s, when Boyd was actively flying, traditional fighter pilot training techniques tended to focus on the method of shooting down the enemy fighter—bullets and rockets—or on providing support to ground troops through the use of bombs. Boyd, however, had a different idea on what was important: being able to place a fighter in the best position to shoot down their opponent.

This meant that in order to be successful a pilot had to be able to get directly behind the enemy and maintain that position for long enough to be able to fire their weapons. At the time, fighter training didn’t prioritize this to the extent Boyd felt it deserved—and when they did teach it, he thought they taught it incorrectly. Boyd’s model of flying a plane was linked to energy; when flying in air-to-air combat, the ability to lose speed rapidly (i.e., dump energy) to increase maneuverability was crucial, as was the ability to regain that speed rapidly. Pilots, however, were being taught to turn their plane in a dogfight by using the stick first, then the rudder; Boyd instead taught his students to use the rudder first, as it led to a greater loss of speed in a shorter period of time—decreasing the turning circle and increasing maneuverability.

Boyd’s approach was not to teach a new method of air-to-air combat, but to teach a new way of thinking, says @craig100m. Share on XIn essence, Boyd’s approach was not to teach a new method of air-to-air combat, but to teach a new way of thinking. Using Boyd’s model, pilots were taught to consider their movement options in terms of airspeed—If I do maneuver X, what effect does it have on my speed, and is this positive or negative for what I want to achieve?—while also considering:

- The countermoves available to the enemy pilot.

- The ability to anticipate those countermoves.

- How to maintain sufficient airspeed in order to counter the enemy’s countermoves.

This essentially turned combat in flight into a game of airborne chess.

The Boyd Effect

Boyd’s theories not only changed how pilots were trained, but how their planes were designed. In 1960, Boyd enrolled in Georgia Tech to study for a degree—his second—in industrial engineering. There, Boyd further developed his thinking into what would eventually become his Energy-Maneuverability Theory. Basically, a fighter plane can be viewed as having either kinetic energy or potential energy. Flying at a high altitude—but at low speed—the plane has a lot of potential energy, but very little kinetic energy. When diving from this altitude to engage an enemy, the plane increases its speed (and hence its kinetic energy) but loses its potential energy (because it is converted to kinetic energy).

This is fine when the plane is attacking, as it allows it the element of surprise, but it leaves it vulnerable to counter-attack; as the plane climbs following the attack, it loses kinetic energy, which again becomes potential energy. This has important implications when it comes to designing a fighter plane; it needs to be light enough that it requires little energy to speed up, but also able to link from one maneuver to another in rapid succession.

As the plane climbs following the attack, it loses kinetic energy, which again becomes potential energy, says @craig100m. Share on XThis was in direct opposition to the approach utilized by the US Air Force when it came to designing fighters, which can be summed up as bigger-higher-faster-further; build planes that can fly higher, faster, and further than ever before, and make them increasingly large. This all came with reduced maneuverability, putting Boyd in conflict with his bosses; Boyd wanted to remove as many extraneous pieces of equipment from his design as possible, but his bosses kept wanting to add things (radar, guns, etc.). Boyd had to compromise on the first plane—the F-15—which came in at 12,000kg (considerably less than its closest competitor, the F-111, which weighed 22,000kg), before getting his way with the F-16, which weighs only 8,000kg.

Relating Boyd to Runners

So what does this mean for middle distance runners? Firstly, the goal in these events, at major championships at least, is not necessarily to run fast but to win. This means that athletes who are able to both dictate the tactical flow of the race and respond to the tactical movements of their competitors are at an advantage. As such, we can even view middle distance races as a dogfight, in which everyone jockeys for the right position to be able to deliver the killer blow.

For middle distance runners, this means they need to be maneuverable; they can modify their pace rapidly in response to tactical changes and possess sufficient speed, acceleration, and agility abilities to get themselves out of tight spots. The flip side of this is that repeated accelerations and changes in pace are relatively expensive from a metabolic perspective. Utilizing training sessions that enable the athlete to develop their ability to change pace quickly and efficiently is therefore important. As an example, instead of running a session of, say, 400m repeats at a given target pace for the whole distance, it might be worthwhile to vary the target times for each 100m split, both within the individual rep (e.g., 14 seconds for the first and third 100m, 12 seconds for the second 100m, and then 15 seconds for the last 100m) and between reps (e.g., rep 1 has a fast first and third 100m segment, while rep 2 has a fast first and last 100m segment).

Boyd’s method of training fighter pilots in line with his newly developed theory was to have a student get on his tail and then attempt to throw them off. The longer the student could stay in the firing position directly behind him, the better they were. Again, this could be used in training for middle distance runners: in training sessions where a group is undertaking training reps together, they could have different roles—one is tasked with setting the pace, one with sticking with him, and one to try and block off any counter moves.

Boyd’s method of training fighter pilots in line with his newly developed theory was to have a student get on his tail and then attempt to throw them off, says @craig100m. Share on XThis is in line with Boyd’s key practical take-homes from his Energy-Maneuverability Theory:

- Having pilots consider their movement options in terms of airspeed while also considering the countermoves available to the enemy pilot.

- Being able to anticipate those countermoves.

- Maintaining sufficient airspeed in order to counter the enemies’ countermoves.

For a middle distance runner, this means understanding their various movement options during a race, the movement options available to their competitors, and how to counter their opponents’ moves and nullify their strengths, under the stress and pressure of a race situation.

The OODA Loop

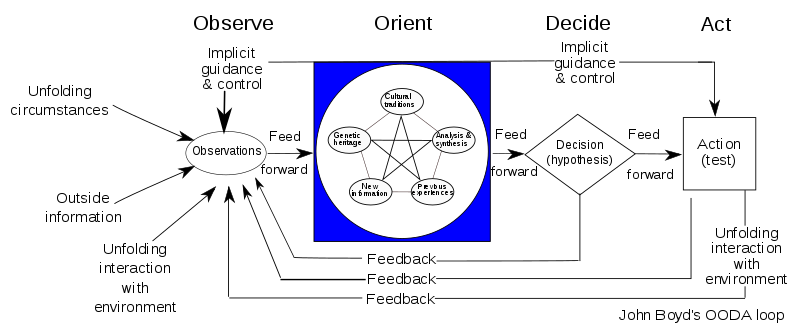

Boyd’s most famous creation, the OODA loop, stands for:

- Observe

- Orient

- Decide

- Act

Here is the OODA loop in diagrammatic form:

This figure makes it look complex, but in essence the OODA loop describes what happens in support of effective outcomes. First we observe what is going on, then we orient ourselves with this information and our own knowledge before making a decision, which we then act upon.

First we observe what is going on, then we orient ourselves with this information and our own knowledge before making a decision, which we then act upon, says @craig100m. Share on XIn air-to-air combat, this would be watching an enemy pilot’s movements, orienting ourselves to their approach (what are they doing and why), making a decision around what to do (e.g., gain altitude), and then carrying out the action. But OODA is a loop, which means we then restart the process: how did the enemy pilot respond to our actions (observation)? The enemy pilot also has their own OODA loop. They watch what you’re doing, orient themselves to your actions, make a decision, act, and then repeat the cycle depending on how you act. The key to success, according to Boyd, is to have a tighter OODA loop than your opponent—you need to be able to observe, orient, decide, and act quicker than they can.

If you’re able to do this, then you can respond to their actions much quicker than they can to yours, leading them to confusion as they try to catch up.

OODA Loop in Running

As you might now be guessing, the OODA loop can be utilized in a tactical middle-distance race. At the start of the race, we look at the start list, understanding the athletes we’re racing against (observation). We then use our prior knowledge of these athletes (their strengths, weaknesses, and tactical preferences) to understand their potential game plan and develop our own approach (orientation). Then, we make a decision on our tactical approach for the race, based on the information worked through in orientation, before starting to deliver that tactical plan in the race (action).

Crucially, however, the process is not finished; we then have to observe the tactical behaviors of our opponents, orienting their actions with both their and our own plans, and then making decisions about how to respond to their movements. Being able to observe-orient-decide-act quicker than our opponents puts them on the back foot; perhaps they don’t respond to a breakaway quite as quickly and so are dropped, or find themselves boxed in close to the inside of the track. As such, middle distance racing is not just a physiological problem to be solved, but it also has a cognitive, decision-making component, which has to be delivered quickly, while fatigued and under stress.

Being able to observe-orient-decide-act quicker than our opponents puts them on the back foot, says @craig100m. Share on XUnderstanding this then dramatically changes how you might design training sessions, because now you have to prepare athletes to make tactical decisions quickly—which involves increasing the library of tactical choices available to the athlete, as well as their ability to think. Similar to Boyd’s Energy-Maneuverability Theory, we can even match tactical behavior with physiological requirements: can our athletes respond physically to the change in tactics that unfolds during the race?

As there are four different stages to the OODA loop, there are four different places that mistakes or errors can occur:

- Errors of observation: the athlete might be fixated on one particular athlete and miss another’s tactical move. Conversely, they might not be tuned in to the need to observe what is going on, and simply don’t have the awareness that they need to be paying attention.

- Errors of orientation: they are unable to adequately understand what is happing in the race—or to do so in a sufficiently speedy manner—and so then cannot make the right decision. Experience likely plays a large role here; more experienced athletes will have found themselves in a wider variety of situations and will have undertaken more orientations under these circumstances, allowing them to become oriented quicker than novices. Exposing athletes to different tactical scenarios, either through racing or training, is therefore an important part of developing a tighter OODA loop.

- Decision-making errors: they have all the information through the observation and orientation stages to make the right decision, but they don’t. Again, this can be down to a lack of experience, further underpinning the need to expose athletes to a variety of different situations that require different decisions be made. Feedback as to the effectiveness of any decision made by the athlete is also important in supporting their development.

- Action errors: in middle-distance events, these are likely to be due to a lack of physical ability (e.g., speed, endurance, agility) to make the required movement—further underpinning the link between physiological and cognitive processes in racing.

Final Thoughts

After Boyd retired, his ideas began to gain traction is the US Military. Dick Cheney, the US Secretary of Defense during the first Gulf War, had met with Boyd many times, and these meetings factored into the development of US Military strategy during the conflict. The US forces were highly agile; they had multiple thrusts against the Iraqi forces which, when combined with deception operations, caused the enemy to struggle to understand what was truly happening and become slow in their decision-making. US forces were able to “get inside” the OODA loop of the Iraqi forces, which enabled them to operate at increased tempo.

It took years for Boyd’s ideas to become accepted, but following the success of the F-16 fighter and military tactics in the first Gulf War, his approach has become far more accepted. There’s something for all of us involved in sport to ponder here—who has ideas or ways of thinking that are truly innovative (and likely not currently accepted), and how can we utilize these ideas before our competitors do? Finally, it took over 30 years before Boyd’s ideas influenced military strategy—can we afford to wait as long in sport?

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF