Let me ask you a question: Have you ever observed or coached alongside someone who just seemed to have a presence? This coach controls the flow of the session in a deliberate way and always seems to have a captive audience. They consistently achieve their desired outcomes, whether that is promoting a high degree of learning, producing incredibly detailed and individualized programming, or delivering a massive amount of energy and “buzz,” no matter the situation.

This experience can be quite hard to describe, but you definitely know when you see it and can almost feel it in the room. Watching good coaches operate—basically the complete opposite of what you see on Last Chance U—you get this feeling of unspoken energy in the room I like to call “session climate.” I use that phrase to describe the intangible factors that go into a good session delivered well.

Watching good coaches operate, you get a feeling of unspoken energy in the room that I like to call ‘session climate’—the intangible factors that go into a good session delivered well. Share on XThere is an old adage that a bad program delivered well will work better than a good program delivered poorly. Now, ideally you shouldn’t ever need to make that choice, but it shows that sometimes what we deliver isn’t as important as how we deliver it and why. Having good coaching processes allows you to achieve a positive session climate consistently.

Bringing the Art of Coaching to Life

This is an area that you don’t really get taught much about at university: You learn the underpinning physiology behind programming decision-making and perhaps why you might use certain training prescriptions. But the major roadblock for many young coaches is finding a way to make the program come to life off of Excel.

Why is this?

Well, unfortunately, there isn’t really any replacement for time spent in the trenches coaching! This is why it is so key for young S&C coaches to spend time coaching, whether that’s with a pro sports team, in a college setup, or just training the general population. You have to go out and coach someone…anyone! This is also why there’s a great benefit to exposing young coaches to multiple environments and contexts—for example, if I spend all my time working with a small group of introverted golfers, I’m going to need to adapt my coaching very quickly if I’m then thrown to the wolves with a group of 30 extroverted rugby players!

To develop this “coaching art,” there aren’t many alternatives outside of spending large amounts of time coaching, often developing your craft through trial and error. This is where working outside of pro sport can be so valuable. It might not be as glamorous, but it is a fantastic opportunity to improve your coaching skills. I worked for a few years at a university and coached so much with such varying groups that I couldn’t help but improve my coaching craft!

One helpful resource is a growing body of literature looking at the “science of the art,” with outstanding work from the likes of Nick Winkelman with his book The Language of Coaching and from Brett Bartholomew and his concept of “conscious coaching.” But as coaches, our default setting when furthering our own learning tends to be to look deeper at set and rep schemes, or to look at why we should or shouldn’t do certain exercises. We often know the what very well, but we tend to let the how develop by accident.

Proper Planning: Checklists & Notes

A way of combatting this problem is to take a personal look at our own coaching processes. It sounds simple, but actually sitting down and working out your own process for coaching is worth investing time in. If we have a good coaching process, we can foster a session climate that is appropriate for the session and the athletes we work with, which will lead to us being much more successful. From there we can develop a coaching checklist that ensures we get the most out of every session, every time.

It sounds a bit silly and certainly isn’t the most interesting of topics, but as some of the great work from Atul Gawande shows, implementing checklists can have dramatic effects1. (See this short clip from his TED Talk—a coaching checklist may not save lives like in this example, but it will certainly save you from delivering a poor session!)

Not only can writing checklists help better prepare you for the session, but it provides a framework for you to more effectively self-evaluate post-session as well, reinforcing the loop of constant refinement of your own coaching process. These might include things you do naturally, such as where you stand in the gym to control the group, or in warm-ups whether athletes go in single file, in small groups, or all at once. Putting some thought into these things helps to sharpen the sword of your own coaching and also allows you to do the “pre-mortem,” as Daniel Kahnman explains in his book Thinking Fast & Slow.

Checklists help better prepare you for the session and provide a framework for you to more effectively self-evaluate post-session, reinforcing the constant refinement of your own coaching process. Share on XForecasting to spot the car crash before it happens allows you to be aware of any potential threats to your session climate and put a plan in place to combat them. For example:

- If I’m coaching one player who really struggles with a lift in a large group of 40 athletes, how much one-to-one attention should I give him if it steals from the rest of the group? Do I have a plan for how I deal with this athlete?

- If I have all my athletes do an exercise, but there are only two pieces of equipment for them to do it on, how do I combat the choke point to the session this might cause?

- If I coach a client one-on-one among a large group of the general population, how do I ensure I still achieve the best session flow?

From making mistakes, you can’t help but find better answers to these questions, which allows you to achieve better session climate, because you are better prepared.

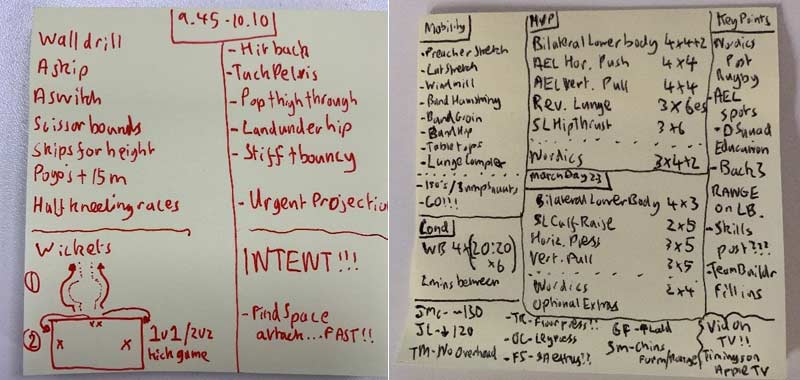

One of the things that I have found helps me personally with my own coaching is to have something to refer to while I am on the gym floor or on the field. I would say the most important tool I have in my coaching toolbox is the Post-it Note…yes, the Post-it Note! I now use small Post-it Notes in pretty much every single session that I deliver.

I am not claiming this will work for everyone, but for me at least, the notes help bring clarity in my own mind of what I’m going to do, what I’m going to say, and key themes (or issues I need to look out for). Just the simple process of writing things down—even if you don’t refer to the notes in session—is said to better commit things to memory2, so at the very least it can help you be more prepared. Sometimes it may be a plan with themes and cues I want to get across; other times I might write an outline of the gym program so I know what the session flow will look like. (An unintended consequence is that I now have the ability to write so small that if I ever went to prison, I’d certainly be the guy tasked with smuggling notes between inmates!)

A formalized coaching checklist doesn’t necessarily have to be written down, but it is good to think about chronologically, so you can visualize the flow of the session. Prior to the session, consider:

- Is the gym well laid out?

- Do my drills on the field flow from one to the next without choke points?

- Do I need a session briefing at the start?

- What themes should I bring up?

- Will I be doing any education?

- How am I progressing the session from the one before?

- Will the athletes know whether they have been successful in the session? How?

- How am I “packaging” the session?

All of these things help the athletes buy in more to what you’re delivering and grow the session climate.

A Bit of Branding

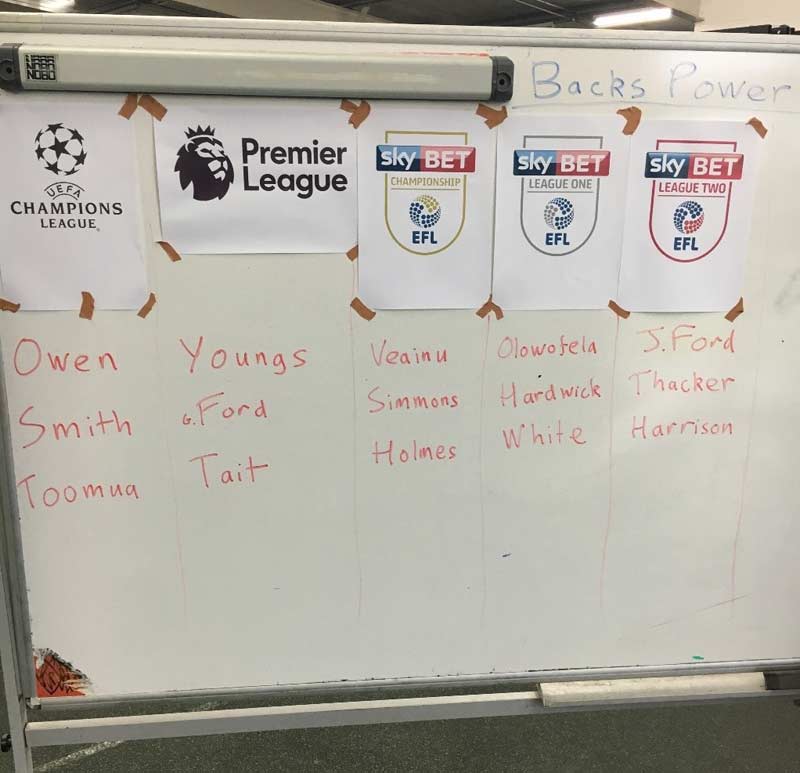

Packaging sessions can be a great way to liven up a generic session, helping to drive training intent. For example, a standard hypertrophy session could be named “Flex Friday,” or you could have certain athletes enroll in “Speed School.” These packaged sessions add an extra bit of window dressing, tend to be more fun, and give the players much greater ownership of the session.

At times, the athletes will see themselves as custodians of that particular group. For example, to join Speed School, the athletes might first need to earn the right to be there (as judged by the players already “enrolled”), performing a particular rite of passage before being permitted to join the group. One example of this from my coaching was a hypertrophy group that required a Great British Bake Off in order to join, where an athlete had to bake a protein-based snack for the rest of the group (with the players of course judging whether the baked goods were good enough to merit entry!). Another example was a speed session with Premier League-style relegation and promotion to the top group, complete with Champions League music playing before the final sled race!

Competition = Intent

One of the easiest ways to affect session climate is by including elements of competition in a smart and simple session design. This is a surefire way to ensure a positive session climate and drive training intent. Adding external rewards such as prizes can work well—for instance, in a rugby environment, I’ve found the players are more motivated to stitch their teammates up than they are to win prizes! So physical punishments or embarrassment for not winning often helps drive banter in the group, as the players are motivated to see their mate have to do something embarrassing or face some hardship.

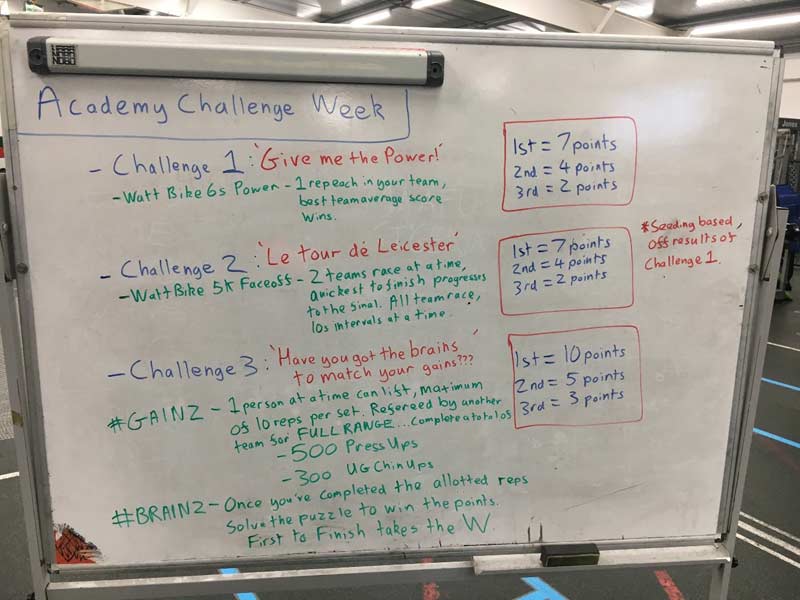

Structuring sessions to include game elements or challenges is also a great way to put a bit of special sauce on a session that can otherwise be quite generic, says @peteburridge. Share on XStructuring sessions to include game elements or challenges is also a great way to put a bit of special sauce on a session that can otherwise be quite generic. For example, when upper body sessions get stale and 5 x 5 becomes too monotonous, a challenge between players to do as many reps as possible in an allotted period of time can be a great change-up.

“Energy” is a term that gets thrown around a lot by coaches, but it is a real thing and the “vibe” of a session can either help give energy to a group or take it away. Energy is a hard thing to put a finger on at times, but it can be controlled by the coach. Depending on your own coaching style, you may be the lead energy guy/gal (think of your college football strength coach in a SMedium polo!), or alternately, you may help certain individual athletes express their own personality to give energy to a group.

This is where allowing your extroverted players to express their personalities can be really useful to provide energy to their teammates. At times, this can be even more powerful than a coach having to always be the driver of energy in the session. The coach can then settle into the role of a conductor, letting the orchestra make the music while you subtly influence the behaviors you want from them in the background.

Being solely reliant on yourself or a few athletes to bring the energy every day is a big ask, so you can make your job easier by letting the environment or task help drive the session climate if the energy is wanting. In a warm-up to get athletes going, playing a couple of fun games that still lead to physical outcomes can be a very effective tool to drive energy and foster a positive session climate.

Videos 1 & 2. Who says warm-ups have to be boring?! You can still achieve maximal accelerations or prepare the players to handle deceleration…it just so happens they are playing naughts & crosses (tic-tac-toe) or running after a rubber chicken! Again, your imagination is the only limiter here.

Gamification of sessions can be a good way of taking the session climate to even better levels. For example, turning a Wattbike session into “Le Tour de Leicester” or having WWE-like Tag-Team Elimination Chamber style max rep challenges with the right group, at the right time, can have a great impact.

This isn’t limited to the gym either; in fact, this strategy works more fluidly on the field in agility and speed games with rules and constraints such as “game-breaker moments” and “power-ups.” This gamification may start out quite abstract in basic tag-based evasion games, but you can actually use it in quite sport-specific drills in a more game speed setting.

Video 3. Gamification works best on-field when tied to the sport. In this game the physical outcome was a max effort acceleration over a large distance, whereas the rugby outcome was kick chase intent and high ball catch skills. In an attempt to tie the two together, the players are in teams that have to score points by cleanly catching the ball in the zone. The further the zone (and so harder the kick and bigger the distance to accelerate over), the more points for your team.

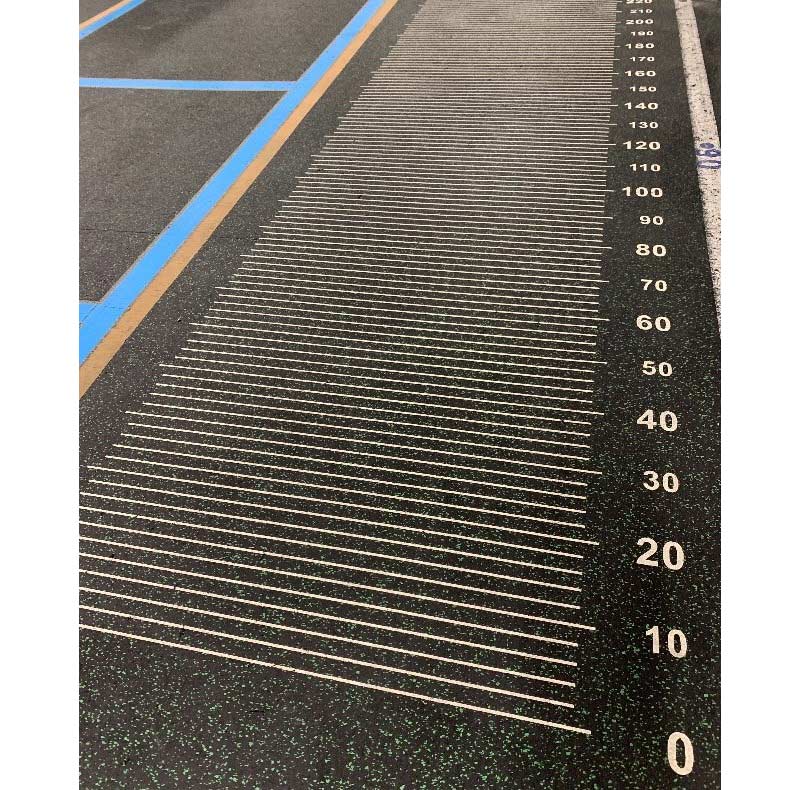

Using exercises that are measurable and then displaying that feedback through leaderboards is a great way to generate competition. This is where exercise selection can be dictated by the ability to drive energy and competition within a group. For example, broad jumps feature significantly in my programs because we have measurement lines heat transferred into our floor—it’s quick and easy to use competition to see who has jumped the furthest because it’s there for all to see.

Another easy way to get athletes to compete is through the use of VBT: Having an iPad feeding back scores is an effective method of creating competition. To optimally improve power, we know that maximal intent is needed no matter the load on the bar3, so finding ways to dictate the environment to get that behavior is key.

A Dose of Our Own Medicine

Once you’ve implemented your ideas and understood your own process, the next thing you want to do is work on refining that process and look for ways to improve it further. At times, this can be tough to do if it’s just you in the gym with your athletes, because you don’t really have anyone but yourself to evaluate how the session went. This can then quite easily lead to you falling into the trap of doing what you’ve always done. But putting some thought post-session to how it went can be key to making improvements.

Sometimes coaching with a GoPro on or at the very least setting up a camera in the corner of a gym can help you understand elements of your own coaching process, says @peteburridge. Share on XAn even better method is to actually record your sessions: We often challenge our players to analyze their performances and watch film of their training and games, but when was the last time you sat down and analyzed your own coaching sessions? It can be quite an awkward proposition to do self-analysis, but sometimes coaching with a GoPro on or at the very least setting up a camera in the corner of a gym can help you understand elements of your own coaching process:

- Have you stood in the most effective position to coach?

- Do you control the group?

- What is your body language toward the players?

- Are there blind spots with athletes’ technique that you miss or don’t see?

- Have you verbalized your coaching in a way that’s easy to understand?

- Do you say enough to impact a player’s movement quality?

- Are you saying too much? (This is where having access to a mic or the Voice Memos app on an iPhone can be very enlightening.)

I’ve found, especially with my on-field coaching, that hearing what I’ve said allows me to be more concise and have clarity with my words the next time I use them. This ultimately improves my ability to coach and allows me to get better at my craft in the same way that I challenge my players to do.

Don’t get me wrong, at times you can get some funny looks if you do coach with a GoPro on or with glasses with a camera attached. But when you get over the awkwardness, the footage you get is fantastic for analyzing your own coaching. Matching this with more formal self-evaluation can be a powerful method to judge your own coaching or model another coach’s style.

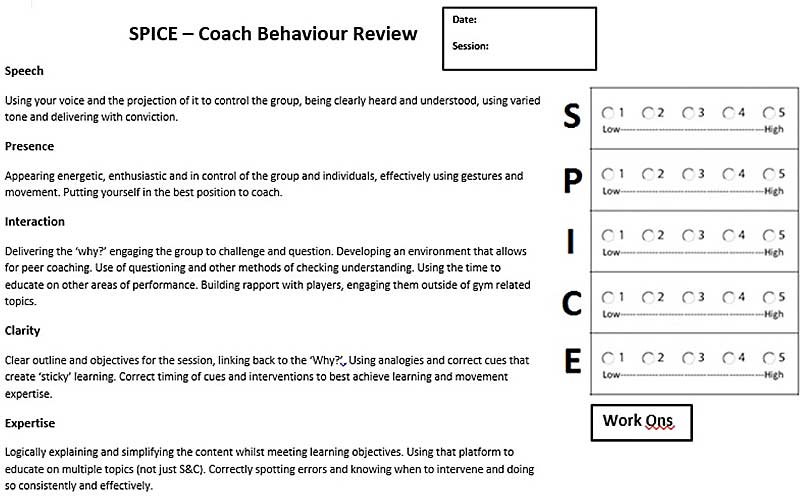

I have adapted the SPICE system used in teaching and public speaking4 to help me better evaluate my own coaching, and from time to time to improve my own coaching process.

Being equipped with higher levels of self-awareness around your own coaching process will allow you to more consistently achieve a positive session climate. This helps what you deliver become a more emotive experience for your athletes and provides the backdrop for so many more positive outcomes. With higher levels of engagement, our athletes buy in and are better primed for more education on what to do and how to do it. This allows us to further influence our athletes’ behaviors (whether in the gym or on/off the field). It is also likely that our athletes will develop greater autonomy over their own development and the training process.

The methods we use to achieve this, whether through competition, fun, greater challenge, or more stimulation doesn’t really matter, as long as it ultimately leads to us being able to better connect to our athletes. If better session climates allow us to do all of that, then we set ourselves up with the best possible platform for our players to succeed…no matter what we decide to program!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Haynes, A. B., Weiser, T. G., Lipsitz, S. R., et al. “A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population.” The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:491-499.

2. Mueller, P. A. and Oppenheimer, D. M. “The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking.” Psychological Science. 2014;25(6):1159-1168.

3. Tillin, N. and Folland, J. “Maximal and explosive strength training elicit distinct neuromuscular adaptations, specific to the training stimulus.” European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2014;114(2):365-374. doi:10.1007/s00421-013-2781-x.

4. Jahangiri, L. and Mucciolo, T. A Guide to Better Teaching: Skills, Advice, and Evaluation for College and University Professors. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 2017.