Regardless of level, a successful coach must possess the skills and knowledge to build trusting relationships, which in turn feed the powerful beast of motivation and effort in an athlete. This is a foundational step to the process, and the quicker a coach is able to do this, the more impactful they can be. The abilities a coach possesses, just like training programs, must be adaptable to the audience or athlete being worked with. There are surface-level differences—e.g., gender, age, sport, etc.—but even deeper-level diversity exists between attitude, life experience, and personality.

Major advances in technology in the last 30 years have created multigenerational gaps between baby boomers, millennials, and generations X, Y, and Z. Being able to adapt to and impact other generations and age groups that you can or cannot relate to has become an important part of the soft skills and emotional intelligence of being an effective coach. It cannot be ignored, and if you are not thinking like this, you are behind.

As coaches, we need to constantly work to expand our bandwidth of operation in the stressful and demanding environment of athletics. We want athletes we work with to be more physically and emotionally resilient and adaptable and we should work to do the same on our end.

Now more than ever, the ability to reframe our approach and address the psychological state is a vital piece of the process of connection, presence, and building a strong, trusting relationship. Physical outputs are obviously important to performance, but if athlete readiness is a psycho-physiological measure, then we need to respect our ability to impact the psychological state of the athlete on a day-to-day level, especially when we are working with them directly. We want not only the training prescription but also the interaction itself to be productive and impactful.

How the Information Age Forges Better Relationships

Just as our approach and interaction must adapt to the athlete, our implementation and effective use of technology needs to have a specific time and place. Velocity-based training (VBT) can be a very productive and impactful piece of the puzzle, but if used haphazardly, it can backfire and not serve as a potential catalyst to providing valuable feedback for both the athlete and coach.

VBT is a potential avenue for working toward a harmonious and productive relationship with the athlete, especially the younger generations, explains @Cody_Roberts. Share on XLet this serve as my disclaimer: VBT is not the answer. Rather, it is a potential avenue for working toward a harmonious and productive relationship with athletes, especially the younger generations and their insatiable hunger for immediate information and reward based on their efforts. Remember, we are ultimately looking to strengthen the coach-athlete relationship, and VBT can serve as an appetizer to the meal of motivation and effort needed to boost psychological readiness and breathe life into a stale and mundane training program.

The Building Blocks of Velocity-Based Training

VBT is a hormetic piece to the training process: When dosed appropriately it can be effective, but too much of a good thing definitely becomes a bad thing. VBT in no way serves as a replacement for learning proper technique and exercise execution or for the vital verbal instruction and feedback necessary from a coach. It is important to remember not to get distracted by the technology. As my colleague Ashley Renteria says, “Tech over tech!” Meaning, technique over technology. With the external feedback and focus that VBT allows, it is all too common for the internal focus of the respective movement pattern or exercise to take a back seat.

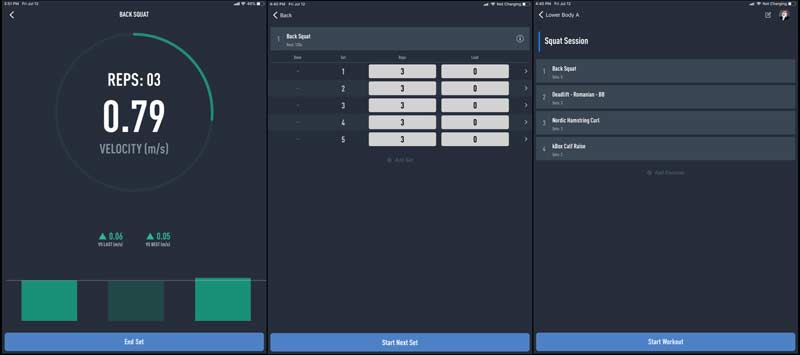

Video 1. The Push App functions as a way to record velocity and transmit planned workouts to the athlete. Every repetition is recorded, including peak and mean velocity, force, or power.

With that additional disclaimer out of the way, let’s shine a light on the positives and opportunities provided by VBT. The prospect of augmented feedback motivates and gives external feedback and focus that improves performance and provides the opportunity for long-term motor learning. This adds a multidimensional layer to the coach’s verbal feedback, showcasing the internal focus and effort with the external result. This not only increases the intent of a respective action (squat, clean, press), but has been shown to promote greater neuromuscular adaptation as well. Inspect what you expect; therefore, measuring the variable you want to attack allows for improvement of it over time with proper training.

Inspect what you expect—measuring the variable you want to attack allows for improvement of it over time with proper training, says @Cody_Roberts. Share on XAdditionally, this feedback creates a competitive environment, not only within the athlete themselves—rep by rep, set by set, or session to session—but also between athletes. Striving to be the best and move the bar the fastest puts the focus not so much on the weight loaded on the bar, but on the speed at which the bar moves. With most sports thriving in a speed/power realm, the majority of training should reflect that.

Remember, our ultimate goal is training transfer, and we are trying to develop abilities that transfer rather than focusing on loads lifted and 1RMs. We know force is a product of mass and acceleration, so by shifting away from increasing the mass in order to increase force and operating where sport-specific speed and power truly live, we focus on the acceleration of an individual or object. That’s what ultimately influences power development, as we know power = force x velocity.

Motor learning, as it relates to power production, comes from how fast, how hard, and through what range of motion an action occurs. This leads to improved neuromuscular adaptations and supports the concept of Dynamic Correspondence, where transfer occurs when training looks and feels like the desired outcome. This is ultimately specificity, and it supports the SAID principle with Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands.

If we are truly purposeful in our prescription, we must continue to ask ourselves: What is the training effect we are after? We are always looking to impose a stress or exercise that helps to form a new ability, habit, or output—consistently. From a philosophical standpoint, there should never be a period of time in which we exclude the focus of acceleration in an explosive manner; looking to enhance an athlete’s speed and quickness from a standstill should always be at least a thread in the rope of a training block.

Keep in mind the objective at hand. If an athlete’s success depends on their ability to move their own body weight, that must be trained. Spending too much time with heavy/slow strength training promotes slow acceleration, which is not wrong, but it may not be transferable or as specific. Surf the curve of force outputs, with time spent using heavy loads and accelerating rapidly with low or relative loads. This can lead to increases in velocity and, in turn, power outputs, increasing the ability to produce force in a shorter amount of time.

Velocity for Biofeedback in Training

The feedback from a VBT device is beneficial for the athlete in both the short- and long-term, and equally helpful for the coach in a number of areas. In the short term, it can be a way to manage the load and fatigue of the athlete, assessing readiness and respecting the day-to-day undulation of the athlete’s psycho-physiological state. With a proper gauge of athlete readiness, the coach can properly dose volume and intensity without forcing either loads (weight on the bar) or volume (sets and reps) that an athlete is not prepared for. On the opposite end, they can “optimize” the loads used or volumes performed. When a coach forces training loads that the athlete is not prepared for, the cost of adaptation is high and associated risks of injury or maladaptation follow.

The most reliable information is multifactorial, so when we combine subjective readiness scores with other objective measures such as bar velocity, we can develop a clearer picture than if we just focused attention on one metric. If an athlete provides a perception of recovery and readiness, we pair that with a vertical jump measurement following the warm-up and then look at relative load-velocity relationships that occur in a back squat. This gives us a more reliable picture of the athlete’s psycho-physiological state.

If perception of readiness and recovery is down, but physical performance is up, it could simply be psychological strain or a monotonous feeling toward the training process—something that urges the soft skills of encouragement and conversation to occur. But the combination of the layers of information helps coaches draw conclusions that can lead them to adjust or modify the training load to promote positive adaptation. That may mean reducing the number of sets, reps (volume), or weight (intensity) used.

Even more immediate, coaches can use VBT to look at velocity within a set to help manage stress and potentially improve the outcome, regulating training loads. With maximal intent, the initial repetitions of a set will be the fastest, but as fatigue sets in, the velocity will decrease within a set. This lets us be more strategic with how close we work to failure, as we know the minimal velocity thresholds that a specific exercise allows (e.g., a squat is roughly 0.24-0.34 m/s).

Ending a set after a specific percentage of velocity loss has proven to be an effective way to help autoregulate training volume and support the training objective. Depending on the focus of the training session or block (volume or intensity), a greater velocity loss (e.g., 40%) would allow for higher repetitions in a set during a focus on higher volumes. Arguably more impactful, during an intensity-focused session or block, we can support the quality-over-quantity mantra and operate at a smaller velocity loss (e.g., 20%). This will help control the volume, promote faster velocity, and lead to the specific neuromuscular adaptations mentioned earlier, resulting in greater power outputs.

An additional way that a coach can use this velocity loss concept is as an opportunity to teach and define rate of perceived exertion (RPE), so that an athlete understands what a six out 10 looks and feels like, versus an eight or nine out of 10. A technique like this allows us to utilize VBT technology to our advantage and positively influence the relationship, as well as the training process, of the athlete.

We can obtain further performance monitoring through the use of predicting 1RM without having to truly experience a 1RM load. This is a space and process that can be all too taxing or even dangerous, and the ability to work in a relative 50-75% load provides a reliable and usable measure to showcase readiness, progress, and performance. The heavier the load, the more accurate the measure, but it is all relative to the athlete and situation. Providing an objective measure with moderate loads can be a productive activity, helping to check the ego of the weight-chasers who measure their success on the “How much ya bench?” mentality.

The VBT Market – Constantly Evolving

The two VBT technology options I have experienced at this point are linear position transducers (GymAware) and accelerometers (PUSH band). In certain circumstances, each tool provides a valid and reliable measure, based on exercise and setup. Ultimately, the more user-friendly experience has come with the PUSH band, especially with the abilities to attach it to the bar directly, toggle between exercises, and not interfere with loading/unloading the barbell.

GymAware may be the more accurate of the two, as it works directly from the tether that operates within the transformer to detect movement and provide a velocity measure. You’d likely expect this physical connection and action to be the more reliable measure, but I’ve also found that the tether gets in the way, slows the process down, and has a tendency to fray and break. Whether you’re looking to obtain the mean velocity for a static exercise like the squat, bench, deadlift, or prone row, or peak velocity from an Olympic-style lift (e.g., clean, snatch, or jerk), GymAware provides the most accurate metrics.

The PUSH band, however, provides velocity via an accelerometer and operates through algorithms devised for each exercise. Some are more accurate and usable than others—most notably the squat, as the bar does not impact the athlete, floor, or bench, causing disturbance or noise with the feedback. Peak velocity has been an unreliable measure for Olympic or ballistic lifts (e.g., jump squats), so I’ve avoided those altogether for the time being. My hope is that the algorithms will improve, and the reliability of the measurements will match the PUSH band’s ease of use. Time will tell in that regard, but seamless operation for training allows the PUSH band to be assistive to the workout itself, providing some level of feedback, regardless of validity, that aids in the motivation and focus mentioned earlier. It also monitors rest periods, as the athlete digitally records each rep and set.

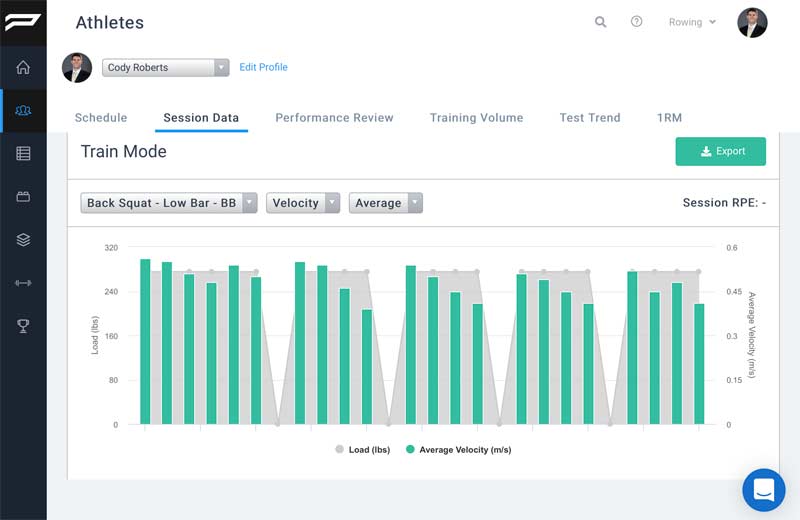

In a holistic effort to quantify training load, session RPE combined with the actual volume load lifted can be helpful metrics for effective athlete monitoring strategies, says @Cody_Roberts. Share on XBoth systems allow the collection of data to be referenced electronically through an online portal. This is what truly enables things to be productive for coaches and athletes—monitoring and tracking performance over time. The paperless world we live in looks to endanger the pen-and-paper training journal by capturing the daily results rep by rep, as the athletes of today operate with a touchscreen and application, entering weights and interacting with technology.

This is why the disclaimer related to coaching and interaction is so important. The ability to collect load and velocity data helps to further quantify the training in the weight room; an area that is too often arbitrarily quantified or neglected in the appreciation of stressors the athlete is exposed to. In a holistic effort to quantify training load, session RPE combined with the actual volume load lifted can be helpful metrics for effective athlete monitoring strategies.

Closing Thoughts and a Final Note on the Program Builder

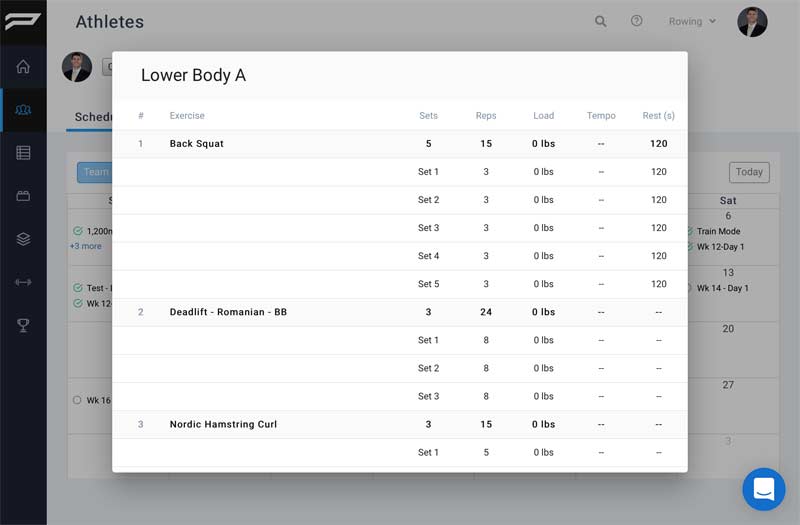

The PUSH portal has an additional use as a program or workout builder. This makes it more like the interaction and potential comfort that the athlete experiences with using a smartphone or tablet application. If the world is paperless, are the days of Excel spreadsheet workout cards endangered as well? Is this the generational gap rearing its head again to challenge us to change, evolve, and improve our effectiveness with the new age athlete?

Creating workouts with Excel is all I’ve known. It allows so much freedom and it’s easy to use: A masterpiece of the vision I have for a block of training including sets, reps, exercises, notes, etc., all beautifully arranged on one sheet and mapped out for the next four weeks. This has served as a communication platform between coach and athlete, guiding the athlete in what they should do when they enter the room. It allows for tracking of information, notes, learning, and better understanding of how this week leads into next week, and showcases the progress of the training block.

Needless to say, I’ve been incredibly resistant to the change and transition to an electronic program builder. However, with the adoption of the PUSH band, it seems like an opportunity to continue to improve the effectiveness and operation of the training process.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF