You are an impostor. Don’t be offended, as we are all impostors. Think of one of the main reasons you became a coach. Was it because of business you didn’t finish in your athletic career? Did you start to prove there was a better way than that of some former coach you really disliked? Is it something you do because of the pull to stay in the sport after immense success as an athlete?

We all come to coaching for different reasons, but what most of us have in common is that we will face impostor syndrome at some point in our career. Most of us thought we knew it all or were desperate for someone to give us a cookie-cutter system that magically produced results. If we coach long enough, we will likely be guilty of both.

As we get better as coaches, it becomes abundantly clear how little we actually know. Interestingly, as we come to grips with this phenomenon, we often become better coaches in the process. Share on XOur development also leads us to apologize to our earliest teams because they are often our guinea pigs. As we get better, it becomes abundantly clear how little we actually know. Interestingly, as we come to grips with this phenomenon, we often become better coaches in the process. As we become more self-aware, there tends to be the emotional creep of impostor syndrome.

Impostor syndrome (also known as impostor phenomenon, impostorism, fraud syndrome, or the impostor experience) is a psychological pattern in which one doubts one’s accomplishments and has a persistent internalized fear of being exposed as a “fraud.”

The good news is that imposter syndrome can lead to positive things. People who don’t feel entirely comfortable with the fear of being a fraud can be highly motivated. We want to live up to the privilege, title, and status that comes from being seen as an expert in the field. However, it is very natural for us to be psychologically in flux about how much of an impostor we really are.

So, how do you determine whether you are or are not a good coach? Is it because you win, have a large team, are respected by your peers, and/or your team has excellent social cohesion? How do you measure those things? Is it just your anecdotal knowledge and experience, or is it because everyone tells you how great you are all the time? As high as those “measurements” can be for us as coaches, do we really want to know the truth? Can we handle the truth?

The Truth Through Science

The scientific method can provide us with the path to know if we are genuinely doing a GOOD job. Some of us who aren’t enlightened might ignore science because it doesn’t fit our world view, or it might point to an inconvenient truth about our place in that world. Are we a net positive, do we deserve the credit we get, or as practitioners of sport are we prescribing the best methods for the athletes we coach?

What do we need to engage in the practice of the scientific method? Hypothesis, findings, discussion (self-reflection), peer review, and further research that eventually corroborates previous findings. Out of all of this, we find emergent truth. The most fantastic thing about emergent truth is that it doesn’t care if you believe in it—it’s just true. One emergent truth all coaches want to know is: Am I good or am I an impostor?

In comparison to other sports, track and field is one of the most objectively measurable athletic pursuits. In other words, it’s a sport where we can see the direct improvement or decline of an individual’s performance regularly. Improved performance is an important variable for measuring the success of our program.

A Hypothesis Through Training Design

Coaches have been smitten with different training philosophies and methods for decades—e.g., Feed the Cats, short to long, the Baylor method, concurrent, and critical mass systems. We often implement these training ideas because we hypothesize that they will make our program better or a group of individuals in our program better. We implement a new drill, workout, lift, or psychological intervention, and we hope to see an improved result through performance.

It is important to note that our hypothesis should not be a shot in the dark or try to reinvent the wheel. Often coaches ignore good science, research, data, and methods. Interpretation can quickly become flawed if we change too many variables. Sports scientists like Bondarchuk, Verkhoshansky, and Morin, and coaches like Pfaff, Anderson, Hurst, Hart, Francis, and Burris have created clear paths to success worthy of exploration. A coach’s hypothesis is only as valid as their commitment to the entire experiment—that is, the track and field season. Once the season finishes up, you get your findings.

Our Findings Through Data

As track and field coaches, we use our findings to determine whether our hypothesis was correct and if it had the results we wanted to see via improved performance for an individual athlete or group of athletes. Additionally, we must also consider in our findings not just how many people improved, but also how many people completed the season without injury or quitting the team. The hierarchy of data should be competitive performance, testing performance, injury rate, and retention. Track and field provides continual data to compare and contrast previous individual performances. Thankfully, due to databases like milesplit.com and athletic.net, we can discern where our training is taking our athletes in competition.

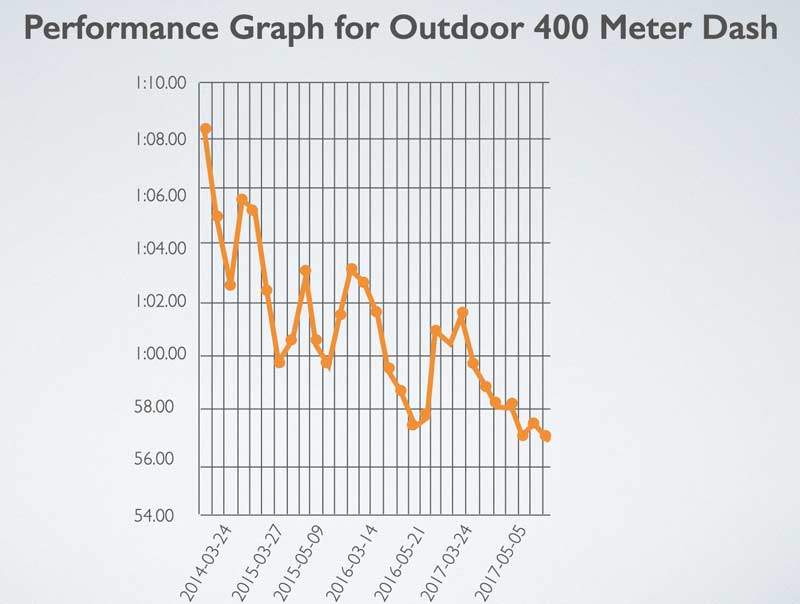

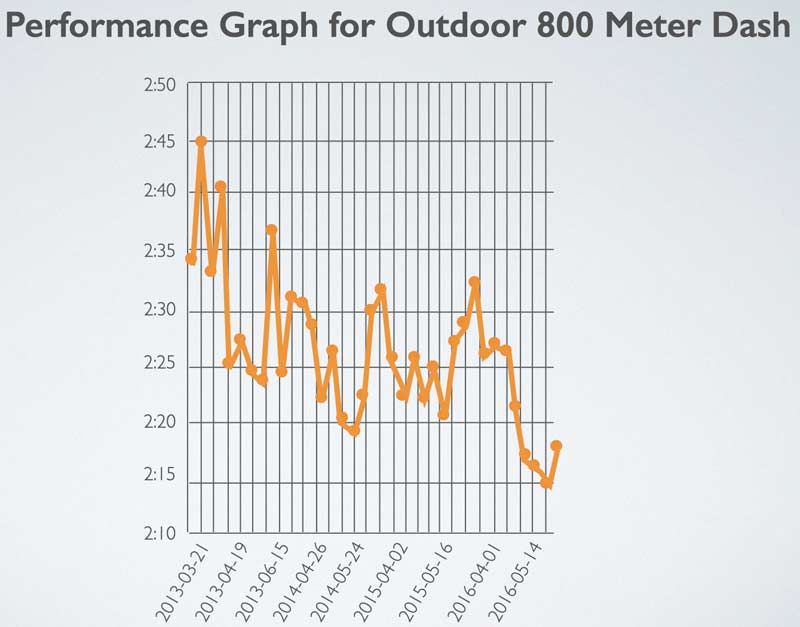

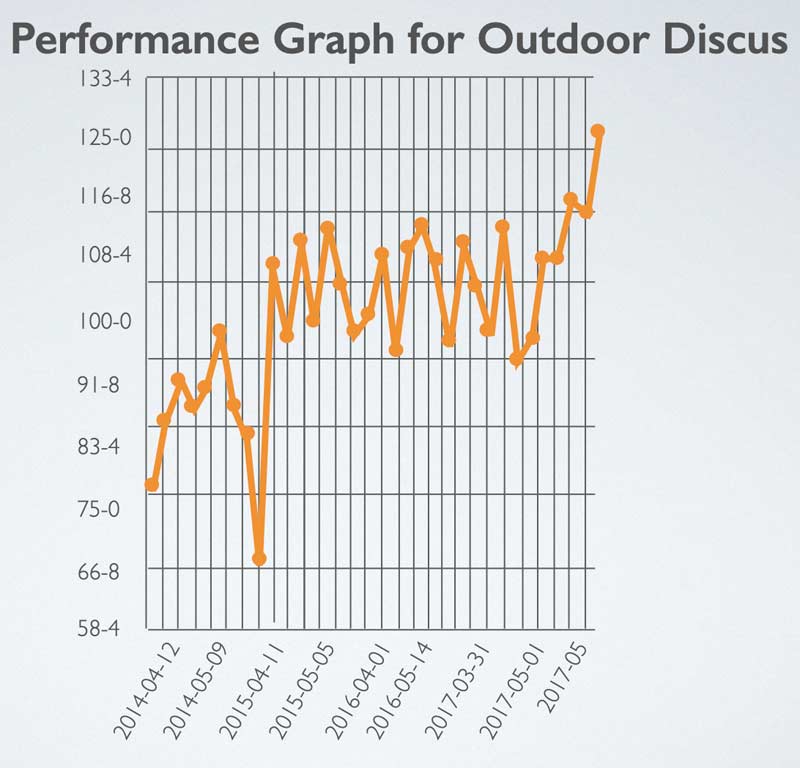

I chart all of my athletes’ performances to track trends during competition. When tracked, a program must show positive returns with elite and average athletes. If your system covers the needs of the sport and the stimulus, you should expect to see these patterns appear each season as the athlete cycles through your program. Progress is significant, and all your athletes should trend toward improvement without any extreme setbacks.

If you coach boys, it is slightly more challenging to dissect progress or chart how useful your program is. Almost all boys get better with maturity from the overload of testosterone. To get a clearer picture through the fog of male maturity, it would be wise to crunch your athlete’s data with other athletes in the area. After about five years, you will be able to see the percentages of improvement. You will be better able to figure out if your athletes are improving at a higher rate than your competition.

For female track athletes, it’s easier to make sense of the data. With girls, these gains are harder to come by because they typically mature sooner and don’t benefit from the same increase of testosterone once they reach high school. Thus, if your female athletes improve throughout their time in high school, you can statistically say with great confidence that your program is net positive over natural maturity.

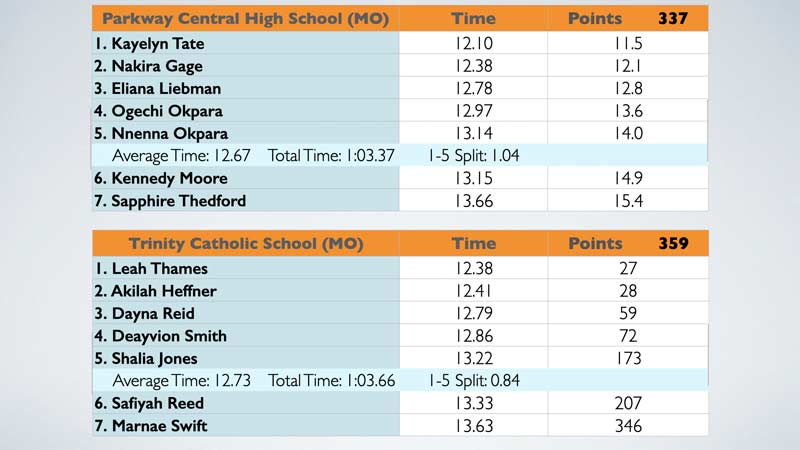

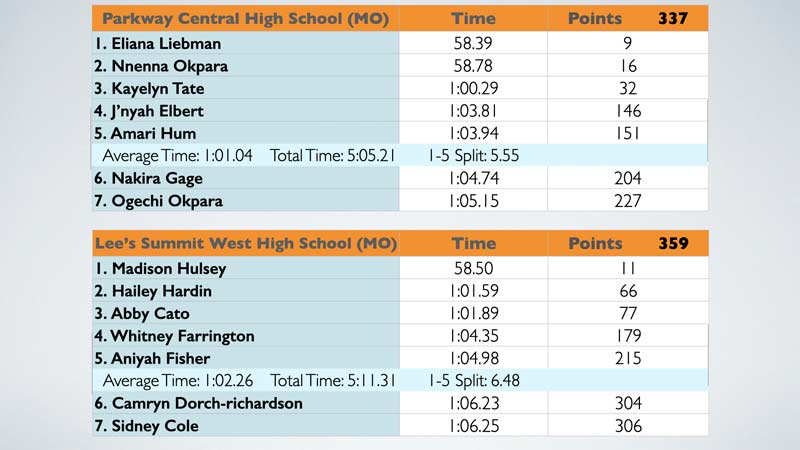

Another essential tool is to compare the average of the entire event crew (sprints) to the top individual performer. Since 2008, most of our state’s top track and field performers have had the majority of their competitions fed into a database on mo.milesplt.com. The database also allows you to trace the statistics of your sprint and distance crew compared to other high school programs. Information can be displayed by conference, region, class, statewide, and nationwide. The data is crunched and scored just like a traditional cross-country team but with the track events (figures 5 and 6).

If you are around long enough, you will coach a good athlete. The question is, does that talented athlete improve? What about building a stable of gifted athletes? As alluring as those individuals can be, we should be more interested in depth.

Crunching the data often reveals that a team that ranks the highest isn’t due to their best kid but to the group as a whole. In our most recent season, I was blessed to have a great year in terms of depth. We were in the top 2 for all three sprints as a team. In the state of Missouri there are approximately 500 schools that participate in track and field, separated into five classifications. My school’s enrollment typically falls around the 80th largest, which puts us in the second classification.

Every year I use the data breakdown to measure what we are doing as a program against my peers. One of my annual goals is to finish the season in the top 20 rankings as a team in the 100-, 200-, and 400-meter dash. Using this as a measuring tool allows us to maintain competitiveness year after year, and also makes sure we are a well-rounded sprint program.

Competitive data is the highest standard in data. Testing has its place and committing practice time to a 45-second run, a standing long jump, power clean, or gauntlet 20-meter fly with a Freelap timing system has value. I’ve written for SimpliFaster before about my thoughts on the importance of electronic timing. However, most of the value is in the athlete versus themselves or the program to itself. Comparing the growth of the individual and raising the floor of the entire program are equally important for a coach to self-evaluate their positive impact across all levels of talent.

The most meaningful data is how much our athletes improve in competition, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XComparing your data outside of competition to other programs has very little value. Testing mostly helps to inform what could be the reason for a lackluster performance or competitive cycle. Typically, we have several athletes who do not test well but perform great on the day of a meet. The opposite is also true for other athletes in our programs. Thus, the most meaningful data is how much our athletes improve in competition.

Discuss, Ponder, and Reflect

When we reach the “discussion” part of our experiment, it is vital for us to ask another question: How do we know we have the athlete in the proper event? Again, testing over a variety of skills and biomotor abilities is critical. It is essential to have many tests to evaluate the athletes who are new to our programs as they join our team for the first time. Frequent and annual testing allow our returning athletes to display new skills or levels of fitness. The data leads our returning athletes to train and compete refreshed with the prospect of new opportunities ahead.

A good coach will take the data acquired and cross-reference it with previous testing periods and seasons. This process helps us design new training and improve training loads. We will also be more adept at placing the athlete with the correct training group or track and field event. Over time, a growing catalog of data shows us what training protocol will increase an athlete’s chance of achieving elite status.

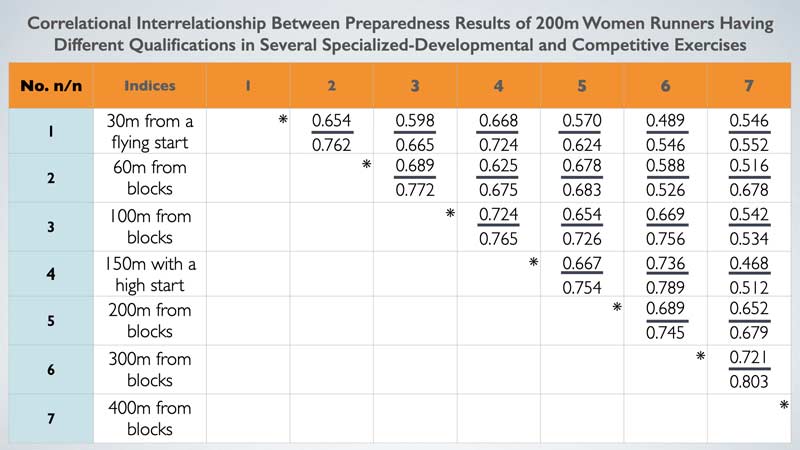

In my program I have found, without a doubt, that a flying 30-meter has a strong correlation to success on the track. However, I would caution against coaches only hanging their hats on maximal velocity tests. Good coaches use a variety of criteria for talent identification and steering subsequent training sessions.

A recent epic conversation I had with Jimson Lee serves as an excellent primer on my testing protocol and what I do. During the season, the athletes reveal themselves through their performances in response to competition and how they adapt to the training stimulus.

It is also essential to change the event menu for athletes in your program. Rotating events accomplishes two things:

-

- It allows athletes to compete in different events,

-

- It enables us to figure out the best event for athletes as we reach the precipice of the championship season.

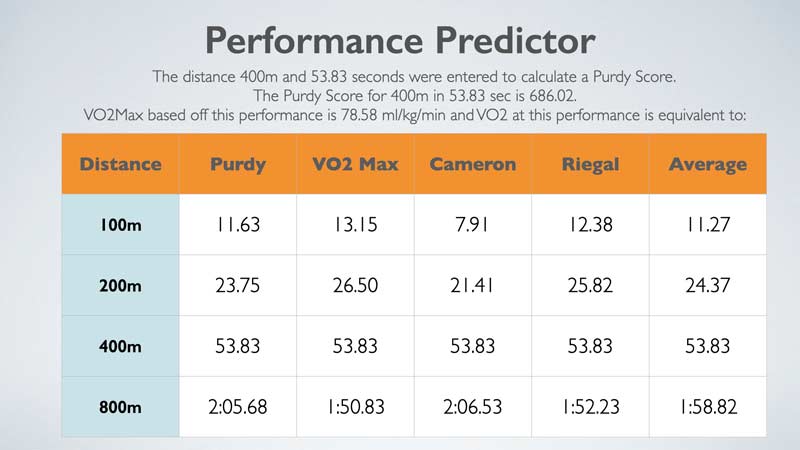

Another tool I use to figure out if I have trained the athlete correctly and what might be their strongest event is this performance calculator (figure 7). If athletes have a better performance in an event than the one they believe is their best event, a good coach will make an adjustment. It’s in their best interest to train them in the event they are ranked highest in, in the state, region, or locality, respectively.

Additionally, if we want to know we are doing a good job, the three nearest performance predictions should be close to what an athlete can achieve in competition. If an athlete’s performance doesn’t come close in the three events they frequently train for, there is a problem. The issue is they are in the wrong event or they’re getting improper training. Worse, it could be a combination of the two.

Typically, it takes about five years to know with some certainty what problems and strengths are a direct result of a coach’s actions, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XIf you are new to coaching or starting a new program without a database of testing and performance outcomes, it won’t be easy initially. A lack of data is one of the many issues that stand in the way of a program getting off the ground. Typically, it takes about five years to know with some certainty what problems and strengths are a direct result of a coach’s actions. In the beginning, it will be critical to glean knowledge from a trusted, successful coach with a system that safely addresses performance potential. To increase our chances of success out of the gate, the mentor chosen should coach in a similar school.

Sport’s Science Considerations

A coach’s intuition should be the hands on the wheel, but science should be the guardrails. Remember, Mother Nature doesn’t care very much what you think or what your plan is. To maximize our efforts, we need to understand the raw materials we will work with through our careers. David Epstein’s acclaimed book, The Sports Gene, dove deep into the ACTN3 gene and its role with elite sports performance. It found a robust link when contrasting the difference in performance potential between CC/CT and TT versions of the ACTN3 gene concerning speed/power athletes. The personal genetic company 23andme has researched the ACTN3 gene in the people who are members of their service.

When looking at the two types of speed-power athletes, in all but one group nearly 50% of the athletes who have potential in power events are a mix of speed and endurance versus speed exclusively. In the absence of a genetic test, it might be unclear where we should start our athlete’s training. Extrapolating data from 23andme lends credence to those of us in the track and field community who are prudently starting our initial training in the middle of the event menu with a 400-meter centric program. Couple our gut feeling with the common genetic dispositions of athletes, targeted testing, and a rotation of competitive outputs, and we will have a clear picture over time what training should be for our athletes. Throughout a couple of months, these factors will reveal what tendencies we should train to maximize a competitor’s performance at that point in their training age.

To be considered a good coach, once those tendencies are clear we need to have a personal discussion on what is the best way to maximize performance for our athlete(s). Russian coach and sports scientist Dr. Anatoli Bondarchuk has done a lot of research on what we should be doing in practice. His set of books, The Transfer of Training, is considered a seminal work on the subject of training stimulus and its effects on human performance.

In the first volume, Dr. Bondarchuk covered a vast array of training and its implication on sport’s readiness. His research studied the effects of specific sports conditioning and ancillary training methods. The emerging truth that came out of his data is that the stimulus that most reflects the actual sport has the highest correlation of improvement to the actual sports performance. The information on top or bottom shows the relationship for elite and sub-elite sprinters, respectively.

For example, in figure 8 below, you can see the best training stimulus is an interval just below or above (100 meters and 300 meters) the race length for an elite female 200-meter sprinter, allowing the athlete to be a little more aggressive/fast short of the distance or stoic/enduring over the race distance. Thus, we need to train maximal velocity for absolute speed. Meanwhile, in the athlete’s best event, we ALSO need to train longer intervals to maximize output for both ends of the race.

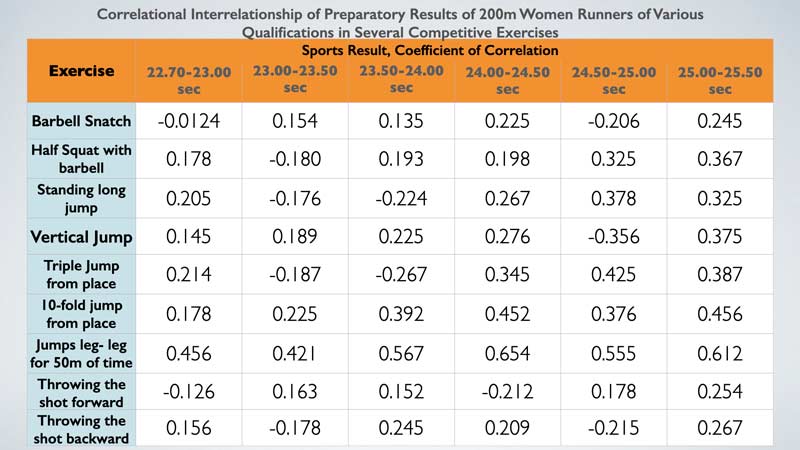

Another aspect of Dr. Bondarchuk’s work is ancillary exercises that can synergistically work with the vital training stimulus to improve the sprinter. Especially as an athlete progresses, it becomes abundantly clear that the critical skill of being able to move quickly requires elasticity. One of the best ways to improve an athlete’s “bounce” is through plyometric movements like repeat bounding. Shown below in figure 9, jump training has the highest correlation to improved sports performance as a supplementary training tool for sprinters.

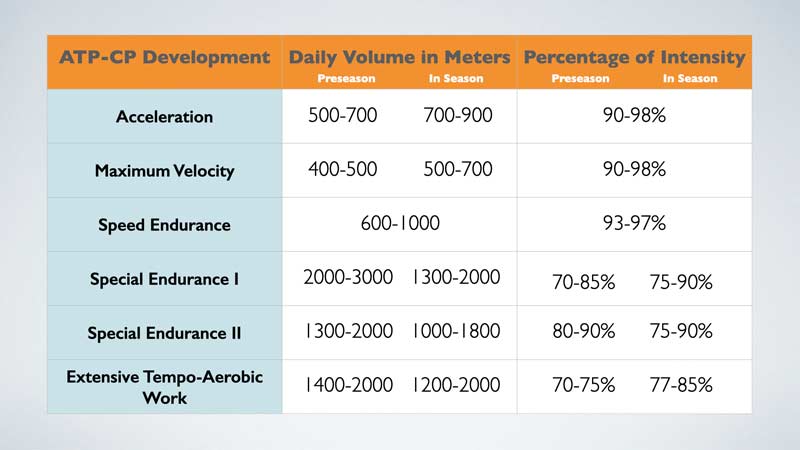

Conversely, in some cases we can choose a training stimulus that can negatively affect our athletes or, at best, is half as effective as other stimuli. For us to do a “good” job, we must be careful about what we choose to do and certainly with whom we do it. Based on our testing, our data, and suggested training load (figure 10). We must put it all together so we can feel less like a fraud or an impostor and more like we are net positive for our athletes.

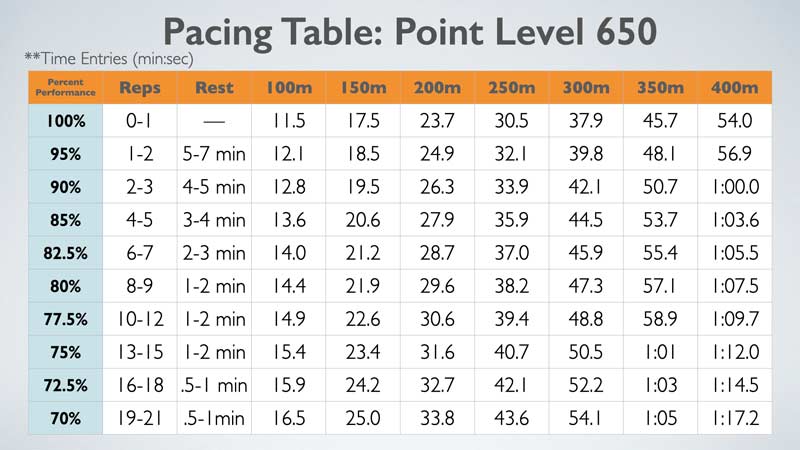

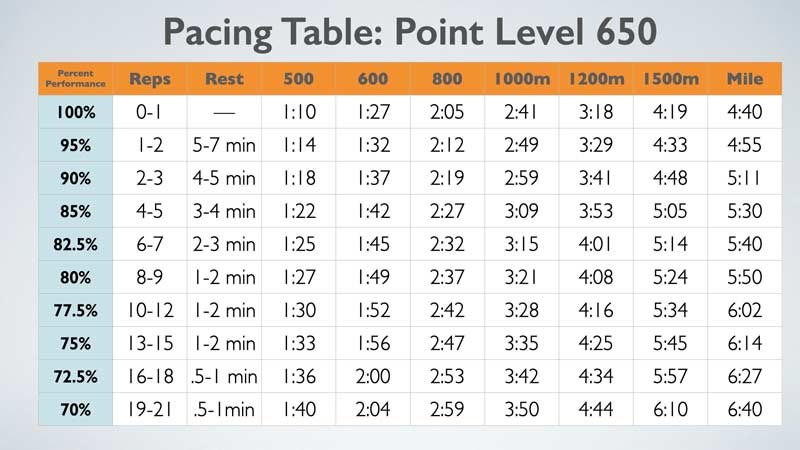

Once we know what to do, it becomes crucial to understand how to do it. For example, creating a training session for sprinters, we must select the right pace and recoveries for the distance we want to train. Messing up these key training parameters could ruin an athlete’s practice or worse. The book RunningTrax (no longer in print) is excellent for assisting you as a coach to select the right distances and intensities. (For another option, I suggest picking up Dylan Hicks’ track & field planner program.) Figure 11 shows a sample of training for what is typically the performance level of a high school All-American.

We can now select the proper training based on the number of intervals suggested from the Transfer of Training with accurate intensities based on that repetition volume. A good coach also breaks down the different aspects of training by modeling the event’s various actual elements. In track and field, we must cue the different parts of the competitive whole.

A good coach breaks down the different aspects of training by modeling the event’s various actual elements, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XRace modeling is an effective strategy. We give athletes visuals through the landmarks (figure 12) and verbal cues as they reach the locations on the track. Good coaching uses science to identify where to place, train, and produce repeated performances that result in their team being steps ahead of their competitive peers annually.

Video 1. A video of me race modeling with my athletes.

Peer Review

Next is possibly the most essential aspect of the scientific method as it applies to proper coaching—peer review. The review requires asking several questions about our training:

-

- Do you coach boys or girls?

-

- Do you have an indoor track?

-

- Do you have an indoor track and field season?

-

- How does your school size play a role in comparison to your opponent?

-

- How competitive is your region?

-

- Do you qualify for championships by performance or placement?

-

- Do you coach multiple sports at the school?

-

- Do you coach XC?

-

- What’s the diversity of your population?

-

- Do you have an outdoor track?

-

- What’s the weather traditionally in your region?

-

- Are you allowed to condition freely in the off-seasons?

We can quickly see how the review of our program can become immense. Instead of getting bogged down in an endless stream of questions, I suggest we choose a different route. Here is a strategy that I have employed to break through the noise that peer review can be. It’s called the “Wooden Project.”

As many of us know, the former UCLA men’s basketball coach, John Wooden, is regarded as one of the greatest coaches in any sport. A large number of books have been written on his time as a coach and his methods. We all know of his leadership pyramid, but what struck me was his willingness to never stop searching and sharing with experts in the field. Every off-season, Coach Wooden targeted a part of his game that “needed work.” He searched out experts in that particular aspect of basketball.

In the book, You Haven’t Taught Until They Have Learned: John Wooden’s Teaching Principles and Practices, the author and former athlete describes the process in detail. Coach Wooden would research who were the experts in something like free throw shooting. He would then send out a survey to those coaches with a series of questions on training design, mental prep, strategy, technique, coaching, cues, etc. for how they attack teaching the skill of free-throw shooting.

The genius behind this isn’t just the information gleaned but also the collaborative effort through peer review. Not only do the answers from the master coaches go to Coach Wooden, but also among all the participants! When finished, he would send the survey with its 10 answers to all 10 coaches who participated. They would get to see and share in everyone else’s answers, thus becoming a better coach based on the advice of the other experts. Every time Wooden did this, his circle of expert coaches, coming from all sports levels, expanded.

Locally, my friends and I have created a coaches’ circle that meets once a month. We rotate houses for BBQ, training talk, and even a book club for our professional development as leaders. Reading Wooden’s book awakened me to the possibility of creating an international circle of experts who could help me “peer review my methods.”

Through the connections I made from Carl Valle and from Mike Young’s website elitetrack.com, I was able to start what Coach Wooden had done decades earlier but now for track and field. Within the first couple of months, the participating coaches got hundreds of pages of responses on various subjects in the sport of track and field. We all became better, and it inspired me to write my treatise on speed: The Sprinter’s Compendium. My purpose was not to share a system that all fundamentalists must follow. Instead, I wanted to pull in experts in different levels of the sport around the world to help young and experienced coaches alike continue to get better.

Compendium: A compendium is a concise collection of information pertaining to a body of knowledge. A compendium may summarize a larger work. In most cases the body of knowledge will concern a specific field of human interest or endeavor.

The resulting compendium was a raw 763-page monster on the subject of speed. Later, I was asked to give my review of different coaches, their methods, and how I knew they were doing a “good job.” As you would expect, methods varied widely. I was lucky to get several, great, abundance-mindset coaches willing to share and critique different methods. Coaches like Tony Wells (Adapt or Die), Tony Holler (Feed the Cats), Mike Hurst (Concurrent), Sean Burris (Critical Mass System), and Dan Pfaff (Flow State) all contributed immensely to the process.

I’m often asked, “who do you think was the best coach or training system?” My response has often been, “it all depends.” However, I have pondered over the years that this might not be the best response. Not because I am trying to avoid being snarky or keep from offending people. On the contrary, the best coaches must adapt to their environment to bring their hard-fought experiences to bear in conjunction with continually evolving sports science to institute best training methods.

However, all of that can only happen if you know the fundamental principles of the event and the sound science that supports it. As coaches, to stay ahead of the curve we must evolve. Not because kids, biological necessities, or human anatomy are different. We must grow because it requires us to continue to get better so we can “do a good job.”

One of the arguments I faced recently in a debate with Tony Holler was that my system is too complex and thus unwieldy for most coaches. My response at this point is that our athletes demand that we get better. Greatness requires effort, time, inspiration, and eventually, innovation. There is no shame in having a starting point, and then cutting and pasting training that is simple.

When I spoke at ALTIS a few winters ago, I argued you must be a master of different methods before you can become a “flow state” coach like Dan Pfaff. In math, before you can do calculus, you must know your multiplication tables; before you can multiply, you need to be able to add. Eventually, what we do might seem very complicated or sophisticated, and often that can be intimidating. It is our job to demystify it for others and show them the path.

So, Have You Answered the Question Yet? Are You a Good Coach?

Here is an interesting dichotomy. If you answered 100% yes that you are a good coach, you have lost your way or haven’t even started your journey as a practitioner of sport. Conversely, some of you might now feel like a fraud. Good news! You and I can get better. There is no such thing as a perfect system. As Dan Pfaff said a long time ago for the Canadian Coaches Centre Podcast: “A perfect system is a weak system because it can be broken easily. Instead what we want to create is a robust system.”

A robust training system will adapt to pressures known and unknown. It will respond…by producing repeatable, consistent, and high-performance results, says @SprintersCompen. Share on XA robust system will adapt to pressures known and unknown. It will respond in kind to the forces trying to destroy it by producing repeatable, consistent, and high-performance results. To do this, avoid becoming a fraud, test new training hypotheses frequently, gather your data, reflect on your results, and have them peer reviewed. Our athletes, peers, and mentors deserve our commitment to a growth mindset as we engage in the never-ending pursuit of becoming a good coach.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF