Have you ever found yourself in need of additional weight for some resisted sled training? You could use your copy of the Sprinter’s Compendium to really load up your athlete’s acceleration training. After all, it’s a hefty tome, weighing in at nearly 800 pages! Let that sink in and imagine the time, effort, and knowledge that have gone into producing such a text. It is certainly not the type of book you read cover to cover in one sitting, but it is certainly a book you should read.

Like many volumes in the coaching or sports performance section of the bookstore (physical or online), the Sprinter’s Compendium is the kind of text that you must visit and then revisit. For those of you who already have some familiarity with the subject material at hand, perhaps you do not need to read the pages in sequential order, but pick and choose the sections and topics you need to address. Given that Coach Ryan Banta’s manual is a substantial challenge to conquer, and assuming you will decide to purchase a copy, you have a lot of reading ahead of you. Therefore, I shall do my best to keep my review short.

The Collected Experiences and Insights of Expert Sports Practitioners

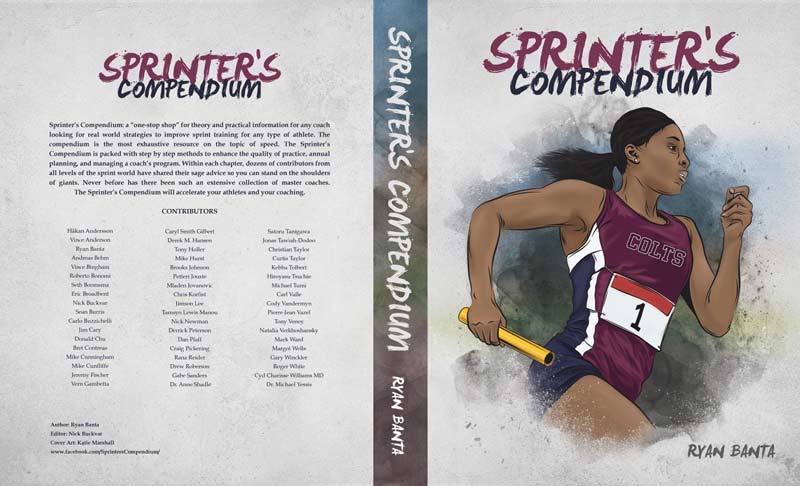

If you flip the book over and scan the back cover, as most people do before purchasing a book, you will see the names of more than 50 expert contributors listed. They provide experience, insight, and knowledge into the seemingly simple, yet deceptively complex, process of running faster.

In the opening pages of the Sprinter’s Compendium, Banta outlines his vision for the book, explaining: “the compendium is designed to help the beginning, intermediate, and elite coaches improve their craft.” Given the enormous diversity in experiences, coaching levels, and positions held by the expert contributors, it is self-evident that this ambitious statement of intent is no glib sound-bite and that the compendium really strives to live up to this admirable but challenging goal.

If you want to gain some idea of the quality of information contained within this book, look at this list of contributors on the back cover. There are dozens of names listed, and I’ll pick out a few that I am more familiar with: Dan Pfaff, Andreas Behm, Derek Hansen, Craig Pickering, PJ Vazel, and SimpliFaster’s own Carl Valle. Among them are elite coaches, sports scientists, athletes, and biomechanists. I was not personally familiar with several of the contributors prior to reading the Sprinter’s Compendium, yet in making my way through the various sections of the text, the value they offered in terms of knowledge, experience, and ideas was very clear.

Given this wide range of experiences, knowledge, and perspectives, the Sprinter’s Compendium is not merely one coach’s treatise on how to train for speed. There are conflicting and dissenting opinions offered, and different coaches’ beliefs and views presented. While this may sound confusing, it is actually a strength of the Sprinter’s Compendium. Through this exposure to opposing viewpoints, the book encourages you to ask questions and think deeper about your own coaching practices, and those of other coaches as well.

In the opening chapter, there is a short bio for each individual contributor. This provides a greater understanding of the background of any individual you may not be familiar with, and imparts a greater insight and frame of reference for their contributions in the forthcoming pages. You begin to get an appreciation for the level of coaching expertise and success brought together in one resource by Banta when you read through everyone’s list of accolades and accomplishments, as well as the lists of their athletes’ records, medals, and successes.

As the text progresses from warmups to starts and acceleration to max velocity sprinting and onward, each expert contributor provides insight on the key concepts of each chapter. This is an excellent addition to the regular coaching handbook—which typically provides the perspective and philosophy of just one or two author-coaches—and gives the reader access to a diverse range of opinions and experience. It is like attending a coaching clinic, with that lengthy list of expert practitioners present in your own living room.

It’s like attending a coaching clinic w/ the expert practitioners present in your own living room. Share on XReaders must remain cognizant that insight is provided by different coaches working in different levels of competition, with different backgrounds and experiences to call upon. Therefore, the onus is firmly on the reader to decide what is relevant and useful to apply to their current situation or environment.

In a field where everyone always wants to know what the Bolts, the Phelps, and the Currys of this world are doing, many budding athletes and coaches miss stages of development by not training appropriately and/or trying to copy the elite of the elite. However, most of us do not work with these populations, or these individuals. The collective insight in this book allows you to see the actions of those in and around your level, demonstrating another major strength of the Sprinter’s Compendium.

The early chapters of the book, which focus on specific aspects of training, present a comprehensive list of drills, including some lesser-known drills—at least, unknown to me as a strength and conditioning coach, rather than a pure track and field coach. The reader also receives explanations as to which elite sprinters use individual drills and why. This helps identify the aspects of performance they focus on.

Another one of the great things in this book is its large library of exercises, which features comprehensive explanations of why you should employ them—to address which issues and get which benefit.

Invaluable sound-bites and coaching gold virtually litter the pages of this book. One specific example is a recounted conversation with master coach, Dan Pfaff, in which Pfaff explains that he noted the football players with the healthiest hamstrings are defensive backs and attributes this to the fact they move through all planes of movement in competition. Therefore, ALTIS coaches incorporate backwards running and multidirectional movement in their warmups.

These little anecdotes make for a more enjoyable reading experience, especially within such an extensive manual, which outlines highly detailed and technical topics. These short narratives really add color to the essential, but occasionally dry, material.

Invaluable sound-bites and coaching gold virtually litter the pages of the Sprinter’s Compendium. Share on XIf I must highlight one weakness of the book, the photos depicting various exercises and drills could certainly be clearer in future editions. Still pictures will always prove inadequate to describe dynamic and complex movements that highly tax athletes’ coordination. This is a general criticism of the use of still photos to describe and explain challenging dynamic exercises rather than an individual criticism of the Sprinter’s Compendium.

On the other hand, whether it is or is not a unique and novel concept, this was the first time I saw QR codes used in a book to link video to a phone screen. These QR code video samples really make up for the limitations of still photos to describe advanced or technical coaching drills.

Follow the Advice That Is Relevant and Resonant for You

There should be no mystery about what to expect in a book of this name. It is a comprehensive reference for everything sprint- and speed-related, from individual drill descriptions to full-session plans for all aspects of sprint training, including sequential and informative progression of the exercises presented in the book. Across every stage and progression of planning, from general to specific preparation and through the “championship phase,” Coach Banta outlines recommendations for beginner or novice athletes, and for the more advanced sprinter.

As I have said before, with so many experts giving advice, the reader must select and use the relevant recommendations that resonate with them. This book offers a large number and broad range of opinions; for example, contrasting opinions on the suitability of prescribing drills. Are they implemented to correct technique? To reinforce posture? Is it just a warmup?

To provide examples, Coach Pfaff asserts that drills merely supply context and seldom transfer to high-speed changes themselves. This is an opinion supported by Craig Pickering, former British Summer and Winter Olympian. By contrast, other contributors believe drills have a larger impact on eventual sprint performance and that they merit a higher priority or intrinsic value for the overall program.

This is no basic plug-and-play or paint-by-numbers handbook. The guest coach contributors routinely disagree in their opinions and philosophies. Another clear example of this is in their consideration of the “drive phase.” Some coaches don’t believe it exists and they don’t even discuss it with their athletes. In these coaches’ views, it is the product of a faulty race model.

Of course, this does not mean you can and should simply ignore those with opposing viewpoints—we should not fall foul of confirmation bias or other cognitive biases. With such a wide array of material from dozens of coaches, the reader will not agree with everything, and that is OK. In fact, it is desirable.

If you only ever read the writings and discuss the opinions and ideas of those you already agree with, you will never learn and grow. You will never understand your own viewpoint as fully as you could and you will never see the possible flaws and faults in your thinking. You will be hamstrung by group think. Although the accumulation of an impressive group of experts brought together by the Sprinter’s Compendium provides a consensus opinion across experts, the onus remains on the reader to utilize what will work in their own environment.

A Wealth of Information, but It Doesn’t Always Flow Smoothly

This manual is not merely a collection of technical drills, progressions, and coaching philosophies. Thanks to the combined years of experience from the assembled coaches, the text contains a wealth of coaching tips and training advice that can only come from those with a lot of skin in the game. An enthusiastic but green coach may have a lot of book knowledge on the science and application of training, but may not understand the logistics and nuances of arranging an effective and free-flowing practice.

For example, Carl Valle provides a “cheat sheet” on managing a block start session efficiently when coaching a group of dozens of different athletes: male and female, tall and short—an assortment of shapes and sizes. This is something you can only figure out after actually being in this situation and having to solve this problem.

Sprinter's Compendium: this is no basic plug-and-play or paint-by-numbers handbook. Share on XThis text is a holistic approach to sprint development with entire chapters and sections on each of the phases of sprinting. Specifically, there are chapters on flexibility and mobility, appropriate strength training, delving into psychology, race modeling, periodization and planning, team culture, and more. Like your carefully constructed training sessions, this book is systematically put together.

Sometimes, however, the flow and progress from one topic to the next is occasionally rough or a bit disjointed. In some places, the order or priorities of information within a chapter is a little confusing. For example, barefoot running appears early in the biomechanics section, before discussions on other arguably greater concerns such as dorsiflexion, posture, etc. Perhaps this is all just a function of trying to include so much information in one manual.

I understand the challenge of putting together a mammoth resource all too well, and ensuring the book’s content progresses in a logical and sensible manner. I am currently putting together my own manuscript, and as I write and write, edit and re-edit, I constantly find myself disagreeing with my own order of the text. I end up editing and rearranging it, and then changing it back.

In truth, perhaps it is impossible to write an all-encompassing manual that makes perfect sense to everyone, and there will always be someone who disagrees with the order and presentation of the material. My harshest assessment is that the project may have benefitted from an external editor.

Start with Inspection, Then Progress to Analysis

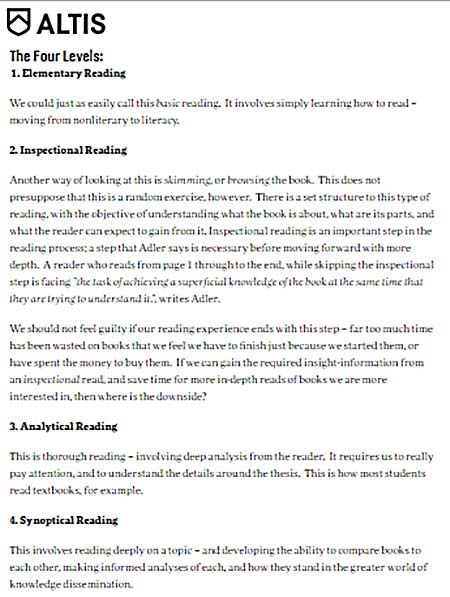

At the end of 2016, Stuart McMillan—Performance Director at ALTIS, and a voracious reader (as most great coaches are)—wrote a blog post on his best books of 2016. In this article, Stuart referenced Mortimer Adler’s guidelines on “how to read a book.” Stuart recounted Adler’s four levels of reading: elementary reading, inspectional reading, analytical reading, and synoptical reading. These levels correspond to: basic reading, skim reading or browsing, thorough reading with deep analysis, and finally, deep reading on a topic with comparison among related books.

Given the sheer volume and wealth of information in this book, this is not a book for easy or elementary reading: The topics, quantity, and details of the information presesented are too vast. Certainly, the reader may be wise to begin with an inspectional read. This is also probably not a text you start and read cover to cover. Pick the areas that interest you at any specific time and then dive into the analytical reading on that topic.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF