[mashshare]

While effective training develops physical qualities such as strength, speed, power, endurance, and other technical, tactical, and psychological elements that are essential for performance, competitive sports offer a separate and unique set of motivational and inspirational factors.

Playing the game offers freedom of movement, thought-free expressions of physical talent and skill execution to achieve a desired result. Players get competition, the challenge of besting a worthy opponent, and the chance to test their ability. The game gives instant feedback—each play, each set of downs, each inning, each half, there is always a precise marker of what the athlete’s efforts have produced to that point. Sports are also unpredictable: Players keep playing because no two games, no two matches, no two races are ever exactly the same.

Players keep playing because no two games, no two matches, no two races are ever exactly the same, says @xrperformance. Share on XWith that in mind, let’s consider for a moment the number of hours your players actually play versus the number of hours they train in order to play. It takes an incredible amount of repetition to induce automation in the execution of a skill or develop the physiological adaptations that lead to increased physical performance. However, how many of those training hours replicate and distort what really happens during the game?

Is there an ongoing element of competition during training or is it a check-marked system of completing sets and reps? Is there freedom of movement, expression, and decision-making from the players, or are drills closed and movements directed? Is there immediate feedback or are gains entirely long-term in nature? Are the sessions planned and predictable?

Transitioning from a Coach-Centered to an Athlete-Centered Approach

During game play, the coach wants the athletes to be active problem-solvers, to correctly assess what is occurring during the game, and to respond with the appropriate decisions and skills. However, it is often the coach who is responsible for all the elements of training, with the athletes having limited input in the training process. This approach is termed a coach-centered approach (CCA).

On the other hand, a player-centered approach (PCA) uses various strategies to enhance autonomy and empowerment, and provides athletes with tools and strategies to manipulate and manage the training process.1,2This article will look at five reasons to consider transitioning from a coach-centered approach to a player-centered approach, as well as how to implement autonomy-supportive behaviors in your practice.

Improve Performance During Competition

Performance in sports relies on the interaction of physical, technical, tactical, and psychological/social factors under complex and dynamic circumstances. During games, players need to not only demonstrate their movement skills, but also make appropriate decisions under pressure. When working with team sport athletes, for example, the first objective of the coach is to establish their style of play or Mental Model. This ideal or “alpha version”—as defined by Richards, Collins, and Mascarenhas3—represents the perfect execution of a skill or play as if it were picked from the pages of a textbook.

But coaches are not the ones playing the game. Therefore, the players’ contributions in reshaping the coach’s vision and making it a Shared Mental Model are crucial. Through team meetings, team debriefs, conditioned or small-sided games, reflection, and questioning, players can take control of their learning. The performance vision offered by the coach and further developed by the players is then shaped by information on the court, on the field, or on the ice. This is only possible if you allow players to provide their input.

Coaches aren’t the ones playing the game. Therefore, you need to allow players to give their input, says @xrperformance. Share on XFor example, players can now anticipate future playing situations based on the Shared Mental Model and/or respond to new challenges as they arise during training. Individual players are now able to coordinate their actions with those of their teammates under various different scenarios. Finally, players can make appropriate decisions during the game and further discuss the new performance vision with their teammates and coaches for the upcoming match. Overall, this approach enables athletes to develop the tactical awareness and understanding to make informed decisions during games.

Improve Feedback from Athletes

In a coach-centered approach, the coach has knowledge of the game and they transmit this knowledge to players. The coach therefore instructs players on the skills and tactics to use during training and games under x and y circumstances. In a player-centered approach, however, the relationship that you create and foster with the athletes that you work with will have a profound impact on their motivation and, therefore, their performance.

Communication between players and coaches is crucial if you are to adopt a player-centered model in your coaching. First, the coach needs to provide a safe environment for players to provide input. During team meetings, for example, this means providing equal opportunities for every player to participate in the team discussion and guarding against one or several players dominating the dialogue. For some issues, this may involve implementing procedures to ensure confidentiality, such as telling players not to include their name on feedback sheets or placing a box or envelope near your office where players can turn in any assignments, feedback sheets, or notes.

A player-centered coaching model relies on the involvement of all players, not just the vocal ones, says @xrperformance. Share on XDuring meetings and training sessions, you should use questioning to get players’ input. By asking a question and providing the athletes with time to answer it, the coach presents an opportunity for the athletes to be active learners and improve their understanding of the task at hand as it relates to the game model.

You can ask two types of questions: low-order questions and high-order questions. Low-order questions support technical development and focus mainly on the what, when, and where. High-order questions are designed to stimulate critical thinking and are mostly about the why and the how.

The implementation of questioning takes time and may be uncomfortable at first. The athletes that you work with may not be used to answering such questions and may be reluctant and intimidated, especially if they need to answer those questions in front of their teammates. The best option for coaches is to plan which questions to ask, and when during a training session they can use questioning.

I would suggest that you start with basic questions and provide athletes with opportunities to answer these questions in a small group. Then, gradually introduce more high-order questions first during meetings and later during team training sessions.

Enhance Motor Learning

I am a firm believer that getting athletes involved in understanding the why is very important for the sports and S&C coaches. In terms of motor learning, I mostly refer to the relatively permanent changes in behavior or knowledge that support long-term retention and transfer.4 When athletes understand why they are performing a specific exercise or why the training program is structured a certain way, they are more likely to understand the concepts leading to performance enhancement.

Involving athletes in understanding the WHY is very important for sports and S&C coaches, says @xrperformance. Share on XThe use of questioning fits nicely in this situation. You can use simple low-order questions (what and where), such as asking the athletes what the acronym PAL means when working on acceleration mechanics (Posture, Arm action, and Leg action) or having them tell you the coaching cues needed to perform a hang power clean (hips back, shoulders over the bar, jump up, and punch the elbows). External coaching cues, such as push the ground behind you (acceleration), punch the ground from above (top speed mechanics) or reach for the cookie jar (shooting a free throw in basketball), are a good way to reinforce transfer of training and learning.

On the other hand, asking high-order questions about techniques and tactics related to their sport or requesting that athletes self-evaluate their performance can also be helpful. Look specifically at the why and the how, and evaluate whether the sessions you planned as a coach ensure the long-term retention of the different concepts the athletes were exposed to in training.

Individualize Training

Once the athletes under your supervision understand the why, you can start to implement different autonomy-supportive strategies. Being autonomy-supportive means that the coach must understand the athlete’s perspective, acknowledge their feelings, and provide pertinent information and opportunities for choice, while minimizing the use of pressure and demands.5 Put simply, that means providing choices, explaining the reason to perform a specific exercise or drill, letting athletes show initiative, and providing positive feedback based on competence and performance.

Traditionally, athletic development coaches or S&C coaches like to use strict training protocols, loads based on %1RM, or repetitions ranges to target many of the different physical qualities required in sports. You can consider this prescriptive style of coaching—where the coach dictates the exercises being done and determines the loading parameters—a coach-centered approach.

In a player-centered model, coaches provide choices based on the athlete’s level of experience. Share on XIn opposition, in a player-centered approach, the coach could look at any of the four recommendations provided by Halperin, et al.6 You could:

- Select the number of choices based on the athlete’s level of experience.

- Provide a range of options to choose from.

- Determine if the choices provided are relevant to the task or not.

- Consider your relationship with the athlete when deciding on the variables described above.

If you use Olympic weightlifting movements in your programming, a good idea could be to outline the different movement progressions that the athletes can perform based on their training experience and technique. If an incoming freshman has little or no experience with Olympic movements, using DB high pulls, DB RDLs, and DB jump shrugs can serve as a proper foundation for that particular athlete. A senior can go ahead and perform more advanced variations, like a power clean from the hang or different pulls.

Another example could be to select a few different exercises that athletes can perform during the in-season, when you don’t know how their body will feel after a game. For instance, a football lineman could choose a bilateral back squat, a single-leg squat, or a leg press as his main lower body exercise for his first weight training session of the week, roughly 48-72 hours’ post-game.

Finally, there are some athletes that you get to know on an individual basis as your relationship with them grows. For example, one student-athlete I worked with in the past two years had a history of knee injuries. His condition was so bad at first that he could only participate in the special teams’ segment of football practices if he wanted to play the game on the weekend. After these 15-20 minutes of special teams, he would pretty much sit out the rest of practice.

Two years later—and after many modifications to his training program—we would have daily discussions before training sessions to assess how he was doing and whether he could perform the training sessions. We often alternated lower and upper body sessions when he felt his knees needed more rest, or limited squats in favor of unilateral posterior chain work.

Increase Adherence to Training Programs

Let’s face it: For some athletes, training to develop physical qualities such as strength, speed, power, and endurance can become quite repetitive, if not boring. You might think that you can only use this approach with fairly advanced or elite athletes. However, you can implement an autonomy-supportive environment with younger athletes as well.

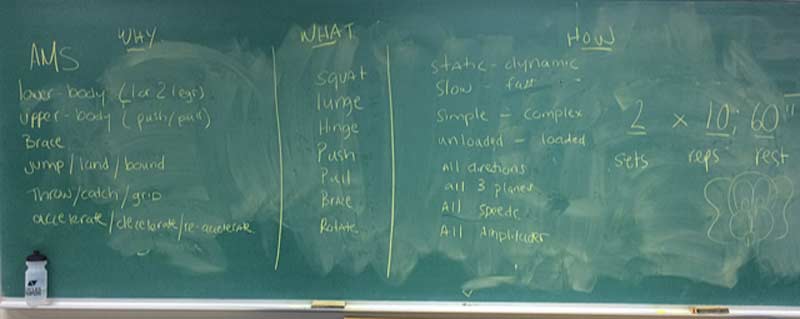

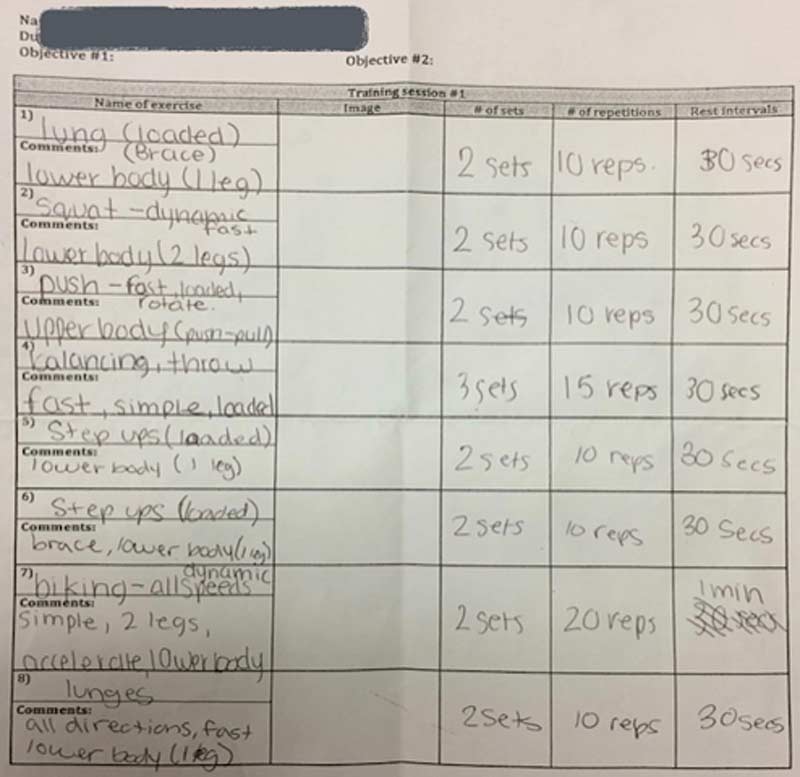

You can implement an autonomy-supportive environment with younger athletes, not just the elite, says @xrperformance. Share on XWhile working with a high school soccer concentration program, I tried such strategies with grade 7 soccer players—both boys and girls. During one of their soccer classes in the weight room, they had to design their own training program for that session. They had to choose between different athletic movement skill (AMS) competencies, then select the movements (squatting, lunging, hinging, pushing, pulling, bracing, and rotating) and the movement progressions.

I was very pleased with the different training sessions these young players came up with. Keep in mind that there were no right or wrong answers, and that I was more interested in their thinking process and their ability to make a link between athletic development in the weight room and their sport of soccer.

Providing young athletes with choices can be as simple as letting them decide whether they want to sprint on a flat surface or on a short ramp, or whether they want to use stairs instead of boxes of various heights to perform plyometric exercises. Telling them to set up an obstacle course using various pieces of equipment and different stations that emphasize footwork, change of directions, jumping/landing mechanics, and running is also fun, and allows them to be creative and involved in the design of the session. Basically, you give them guidance in setting up the exercise based on the theme, skills, or physical qualities you would like them to improve.

Give Them Choice and a Voice

When working with athletes, the role of the coach is to plan, organize, monitor, and respond to the different circumstances that evolve around the training process. At the beginning, this certainly entails providing more guidance and more direction on the different aspects of the training. However, as your relationships with your athletes grow—and they mature and gain a better understanding of themselves, their needs, and their sport—your role as coach is not to tell athletes what to do, but to set up learning opportunities that enable them to figure it out themselves.7

Giving athletes choice and a voice is an important starting point for their enjoyment of the game, says @xrperformance. Share on XProviding athletes with choices and a voice in the training process can therefore serve as an important starting point for the athletes that you work with to realize the beautiful joy of the game.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- Kidman, L. (2005). Athlete-centred Coaching: Developing Inspired and Inspiring People. (T. Tremewan, Ed.). Christchurch, New Zealand: Innovative Print Communications Ltd.

- Sheridan, M. P. (2009). “Coaches Empowering Athletes … Using an ‘Athlete-Centered’ Approach.” Podium Sports Journal.

- Richards, P., Collins, D. & Mascarenhas, D. R. D. (2012). “Developing rapid high-pressure team decision-making skills. The integration of slow deliberate reflective learning within the competitive performance environment: A case study of elite netball.” Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 1-18.

- Soderstrom, N. C. & Bjork, R. A. (2015). “Learning Versus Performance: An Integrative Review.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 176-199.

- Mageau, G. A & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). “The coach-athlete relationship: a motivational model.” Journal of Sports Sciences, 21(11), 883-904.

- Halperin, I., Wulf, G., Vigotsky, A. D., Schoenfeld, B. J. & Behm, D. G. (2018). “Autonomy: A missing ingredient of a successful program?” Strength and Conditioning Journal, (February).

- Kidman, L. & Lombardo, B. J. (Ed.). (2010). Athlete-centred Coaching : Developing Decision Makers. Worcester, UK: Innovative Print Communications Ltd.