[mashshare]

Eric Renaghan was named the head of Strength and Conditioning for the St. Louis Blues (NHL) in 2016. Prior to his position with the Blues, he held the title of assistant S&C coach for the Vancouver Canucks. Eric is currently completing his graduate studies in biomechanics at Lindenwood University. His main interest is in neuromechanics and movement expression as it relates to sport performance.

Freelap USA: Force analysis with jump training has a lot of coaches wondering how valuable the information is for prescribing training. Could you take a few metrics you collect from your system and share how they help tailor your strength training? Also, could you get into workflows of how you are able to run so many tests without interfering with the training when faced with little time?

Eric Renaghan: The real value in measuring force output through jump performance, as I see it, is being able to bridge the gap between the objective quantification of force production and affecting the quality of an athlete’s force application.

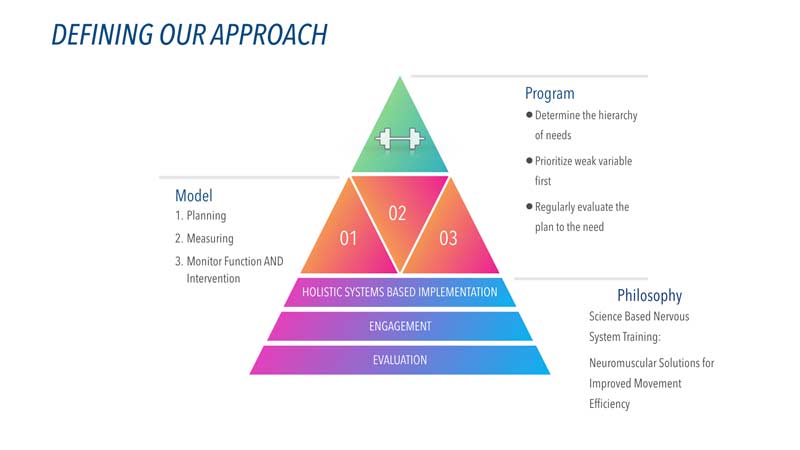

I can’t lose sight of the fact that my job is to complement the sport skill of our guys, while simultaneously effecting more robust and sustainable performances over time. This prompted us to ask ourselves how we can develop a model where we could assess and improve our athletes’ quality of movement expressions regularly and in an efficient manner. The quick and reliable insight that force plates provide into the strategy athletes choose for movement led to the counter movement jump (CMJ) with free arms becoming our weekly go-to assessment. Interestingly, vertical jump performance was found to be the strongest predictor of football playing ability. (Sawyer et al., 2002)

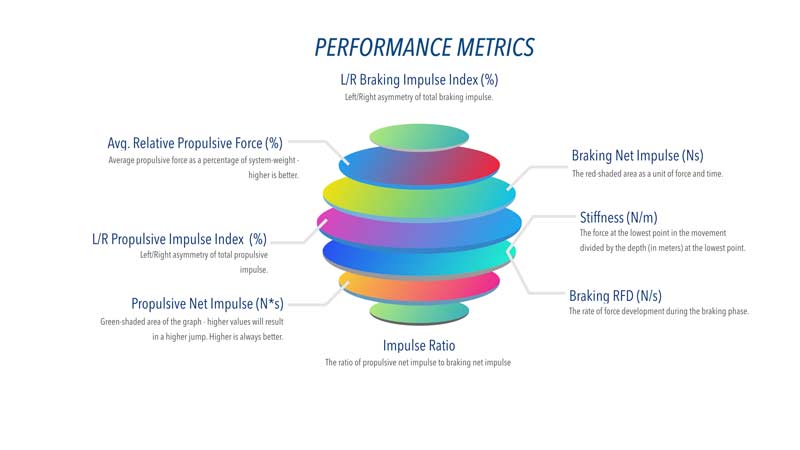

The next question we had was, “how do we seamlessly integrate this ‘testing’ into the regular training routine?” We answered this question by standardizing our assessment procedures, “jump” days, and the variables we collected. Of the 42 CMJ variables provided by our software, there are eight distinct metrics selected from the entire force/time signal that directly drive our training prescriptions. Some of those underpinning values of our programming include braking net impulse, avg. relative propulsive force, braking RFD, propulsive impulse, and stiffness.

These selected variables are aligned with relevant performance metrics to establish a hierarchy of needs for each athlete. For example, what on-ice KPI are we hoping to improve and where do we need to direct our training to get there?

We score the raw data we collect against each athlete’s prior round of jumps, their positional group peers, and finally, the entire team. Our training prescriptions prioritize their weakest variable with a directed emphasis on improved efficiency of movement expression. From a programming perspective, I have to be honest and admit that we don’t have much variety as it relates to our actual exercise selection, but we do vary sets, reps, and intensities to change the overall stimulus.

Every movement in our library has a specific expected outcome and if it doesn’t lead towards improvement of the training goal, there’s no room for it in our program. Love it or hate it, we often get judged by game performances of the athletes that we work with so we are constantly validating and improving our assessments and prescriptions.

Freelap USA: Speaking of training, in-season training requires a balance of compromise and a firm grasp of the goal of challenging the body. Can you explain how you overcome logistical challenges and fatigue during the season and push the athletes without exhausting them? It seems a lot of coaches have either given up and focus on recovery or blindly just load and hope. Anything middle ground?

Eric Renaghan: Without a doubt, the sheer density of our game, travel, and practice schedule makes training time a rare commodity. Maintaining motivation in the middle of January after a 10-day road trip can be a huge challenge. As we look to address the changing needs of each player, we are very cognizant of how the work we ask them to engage in not only affects them physically, but mentally and emotionally as well.

With that said, I believe the transparency of the data from our force plates gives our athletes a strong sense of ownership and clarity over their in-season programs and goals. That equals more time to invest in solutions that hopefully slow down the rate of fatigue and levels of training soreness that can become problematic as the season goes on.

The transparency of the data from our #forceplates gives our athletes a strong sense of ownership, says @EricRenaghan. Share on XTim Pelot summed it up well when he recently tweeted, “In many situations, the influence of intensity overrides the influence of volume.”

Finding a middle ground in-season is difficult but possible, and there are absolutely occasions when we need to be flexible with our asks in order to get there. Allowing the athlete to have choices is often frowned upon within our culture, but it can be surprisingly effective.

For example, a trap bar dead lift is a solid choice of movements for driving force production but, when the situation calls for it, we can offer the barbell push press as an alternative. Both options target their weakest variable and while one may have more effect than the other, they will both always support the goal. Once the movement is prescribed, the intensity the athlete works up to is the same as they would work to in their off-season program; however, they only have one set at their highest intensity. By keeping the intensity up and volume down, we achieve an overriding stimulus and remain focused on maintaining healthy force-producing athletes.

Freelap USA: Player speed is a major factor in sport, and ice hockey is no different. Could you talk about how you manage this variable and how you either develop it or sustain an athlete’s talent? With athletes coming in nearly finished, is there room to grow?

Eric Renaghan: Speed is highly valued and anyone who has seen Connor McDavid skate will tell you that it really is a differentiator, but what does skating fast actually look like? It is very rare that what we do in the gym will have lasting impact on attributes like stick handling, passing, or “hockey IQ,” but with the understanding that genetics play a role in how much improvement may be possible, I do think we can contribute to improving the application of speed.

This description on athletic movement from the IAAF’s Introduction to Coaching Theory translates well to hockey, in my opinion. “In athletics, movement is usually a combination of linear and rotational motion and is called general motion. A sprinter’s body, for example, has linear motion but the movement is caused by the rotational motion of the legs. Both forms of motion take place to produce the general motion of running.”

Through collaboration with our power skating coach and observation of our guys playing hockey, we have gained valuable insight into skills like skating motion required for change of direction, accelerating out of the zone on a breakout, or how an athlete drives through the neutral zone on an odd-man rush.

Force plates and our skating coach’s technical expertise help us decide what part of speed to train, says @EricRenaghan. Share on XOur force plates and the technical expertise of our skating coach help us decipher what part of speed we actually need to prioritize in training (i.e., force, impulse, stability, etc.) We then anchor that neuromuscular solution to the technical skill that gets trained on the ice, in turn equaling better skating performance.

Freelap USA: Conditioning during the season seems to be about games and sometimes a few easy practices as the pendulum has swung towards recovery over preparing. Could you share how you evaluate player fitness during the season and during camp when you get athletes in from different off-season programs?

Eric Renaghan: One of the toughest things to do in our sporting culture is to challenge the way things have always been done. I think there are too many shades of grey on what the perceived conditioning needs are for hockey. To have my voice heard on a topic that is traditionally owned by the coaching staff required me to simplify the language we use to describe our findings so the coaches and GM could quickly make decisions on what they wanted to do. Do we rest or do we practice harder? Our information has to help drive those decisions.

We have had some success using the Firstbeat system in creating a metabolic signature for each of our players though monitoring real-time training effects and aerobic/anaerobic differentials during our conditioning tests in camp. Our “conditioning” testing battery consists of one anaerobic and one aerobic assessment:

- Test 1 is the 45-second Wingate on the Watt Bike. We do this for two reasons. :30 max effort doesn’t really represent a shift in hockey, so we wanted to get it closer to the work/rest ratio of a game. There is :10 max, :05 recovery, :05 max, :10 recovery, :05 max, :05 recovery, :05 max—and we look at peak effort 4x. Fatigue index is the 4 peak efforts… Can they generate power at the end of the shift?

- We still want the max power a Wingate gives, so we start it with a :10 max effort. Test 2 is a modified on-ice “beep test.” Each level must be completed in eight seconds, for a total of 64 seconds of skating per stage. A 56-second rest is provided between each stage. The first stage of our protocol involves skating from the goal line to a cone 29m away and back, for a total of four roundtrips, with the cone for each subsequent stage being 3m further away. This protocol provides us with a really accurate representation of skating skill and aerobic fitness. Parts of this test also guides our conditioning return-to-sport requirements.

No matter what choice the coach makes as it relates to practice, we have to make sure the athlete is ready to meet the goal set each day. These two assessments have helped us identify what we need to focus on to ensure their readiness.

Freelap USA: Injuries around the groin area are complicated—can you talk about what unconventional ways you approach the problem? Hockey isn’t plagued by hamstrings but do seems to have unique injury patterns that you see more of. Can you get into some fresh perspectives instead of doing strengthening and mobility exercises?

Eric Renaghan: This is a great question! As the season goes on, we often observe a common defensive mechanism begin to show itself. Maybe the guy that averages 30 minutes per night got crunched into the boards a week ago or maybe he just didn’t train very well in the off-season. Whatever the cause is, we often see restricted ranges of motion appear and that is a major red flag for us.

The athlete feedback in this scenario is often that they feel “tight.” Understanding the context of this feedback gives us a better roadmap to understanding where we truly need to spend more time directing intervention. In my opinion, tightness usually has less to do with muscles, tendons, or joint structure, and more to do with neuromuscular safety mechanisms restricting normal ranges of motion. Counter movement jumps have been extensively studied as a means for determining lower limb neuromuscular function. (Mundy, Lake, Smith & Lauder, 2017)

I believe tightness has more to do with neuromuscular safety mechanisms restricting normal #ROM, says @EricRenaghan. Share on XAs I mentioned earlier, we go back to our force plates to understand how an athlete sequences their movement expression. The lack of extension of a movement is usually reflected by an overall lower duration of force production—specifically, propulsive impulse. When propulsive impulse is diminished, the athlete is forced to limit their stride extension. This can certainly be one of the reasons for groin injury occurrence with the lateral pushing requirement of skating.

As an athlete continues to become more explosive, the requirement to dissipate forces becomes greater.

One of the more common groin situations occurs in defensemen and goalies. They are both obviously quick and explosive, but D-men are further challenged by the need to skate backwards, forcing a shorter working range of motion. The training prescriptions we employ not only look at improving the quality of force production of each athlete, but also identifying who needs more mobility and flexibility and who needs more stability.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]