Many sport professionals believe that the quality of movement, the running and sprinting mechanics, is a big factor in the occurrence of non-contact injuries. When a player suffers a hamstring tear during a sprint, we look at the footage and oftentimes see poor form. We then focus on fixing the technique and correcting the player movement strategy. But the body isn’t ignorant and rarely chooses a suboptimal and potentially dangerous movement strategy due to ignorance. Often, the poor form we diagnose isn’t the problem but a symptom.

The easy assumption is always to blame strength and mobility. However, unless previous injuries are compromising a specific muscle group or an anthropometric particularity represents an anatomical challenge, lack of strength and/or mobility is very likely a symptom rather than the problem itself.

What if emotional state and its subconscious effect on movement pattern was the problem?

The easy assumption is to blame an athlete’s injury on their lack of strength and mobility. But what if their emotional state and its subconscious effect on their movement pattern was the problem? Share on XIsn’t it rather interesting that strength and conditioning coaches, medical experts, and sport scientists all still debate fiercely why hamstring injuries are still a high occurrence in team sports despite all the knowledge and best practice guidelines produced on this muscle group’s mechanics? All teams have specific hamstring strength protocols and teach running and sprinting form, but injuries are still happening. However, quadriceps strains are not that much of a hot topic.

In the medical world, back pain is a scourge. It is such a widely present and complex issue that such a thing as “non-specific back pain” is an accepted diagnosis. However, people do not queue at the physiotherapist’s office to get their non-specific abdominal pain relieved.

Calf, hamstrings, low back, neck—most injuries or painful problems happen at the back of the body. Strength and conditioning programs emphasize posterior chain “prevention” work and pre-habilitation protocols more than they do the anterior chain. Has Mother Nature made us with a big flaw, a fragile backside that we ought to correct, prepare, and treat so as to be able to go through our lives without breaking?

Of course not.

Evolution and Survival Phenomenon

If we do have more pain and injuries at the back of the body, it is for a good reason. Our front side is where all the vital organs of the body are located. Our eyes (allowing us to see threats and connect to the world); jaws, tongue and throat (without which we can’t be fed); the lungs we need to breathe, the heart, stomach, liver and reproductive organs—all are located on the front side of the body. Hundreds of thousands of years of evolution have made us absolute masters at protecting our front.

If someone launches a punch toward your face, in a fraction of time, your hands will have raised up and protected your eyes and jaws. If you stand in the way of a powerfully kicked ball, in less time than it takes to breathe, your shoulder will come down to protect the lungs and heart, your arms will tuck in front of your abdominals protecting the liver and stomach, and your knee will raise toward your arms to save the genitals. If you have the time, you may even rotate, giving your back as a shield.

Maybe even more telling is to observe a fighter as he goes down. Lying on his side, his arms are on the sides of his head, his head tucked in toward his chest, his shoulders and chest curved inward, and his hips and knees flexed and raised all the way as to touch his elbows. In that curled-up position, he knows he can take more hits, he can endure more suffering; waiting for the referee to stop the beating, his survival is almost guaranteed.

The takeaway message is clear. The body will always sacrifice the back to save the front. Understanding this survival phenomenon, which is beyond our conscious control, can lead to two realizations with regard to injury prevention.

The body will always sacrifice the back to save the front. Understanding this survival phenomenon, which is beyond our conscious control, can lead to two realizations about injury prevention. Share on XFirst, not everything is as simple as A=B. Hamstrings pulls are not always the consequence of improperly managed training loads, bad sprinting techniques, or poor muscular strength. No muscle ever gets injured alone, and none ever heals alone. We tend to be obsessed with very local questions and disregard the global.

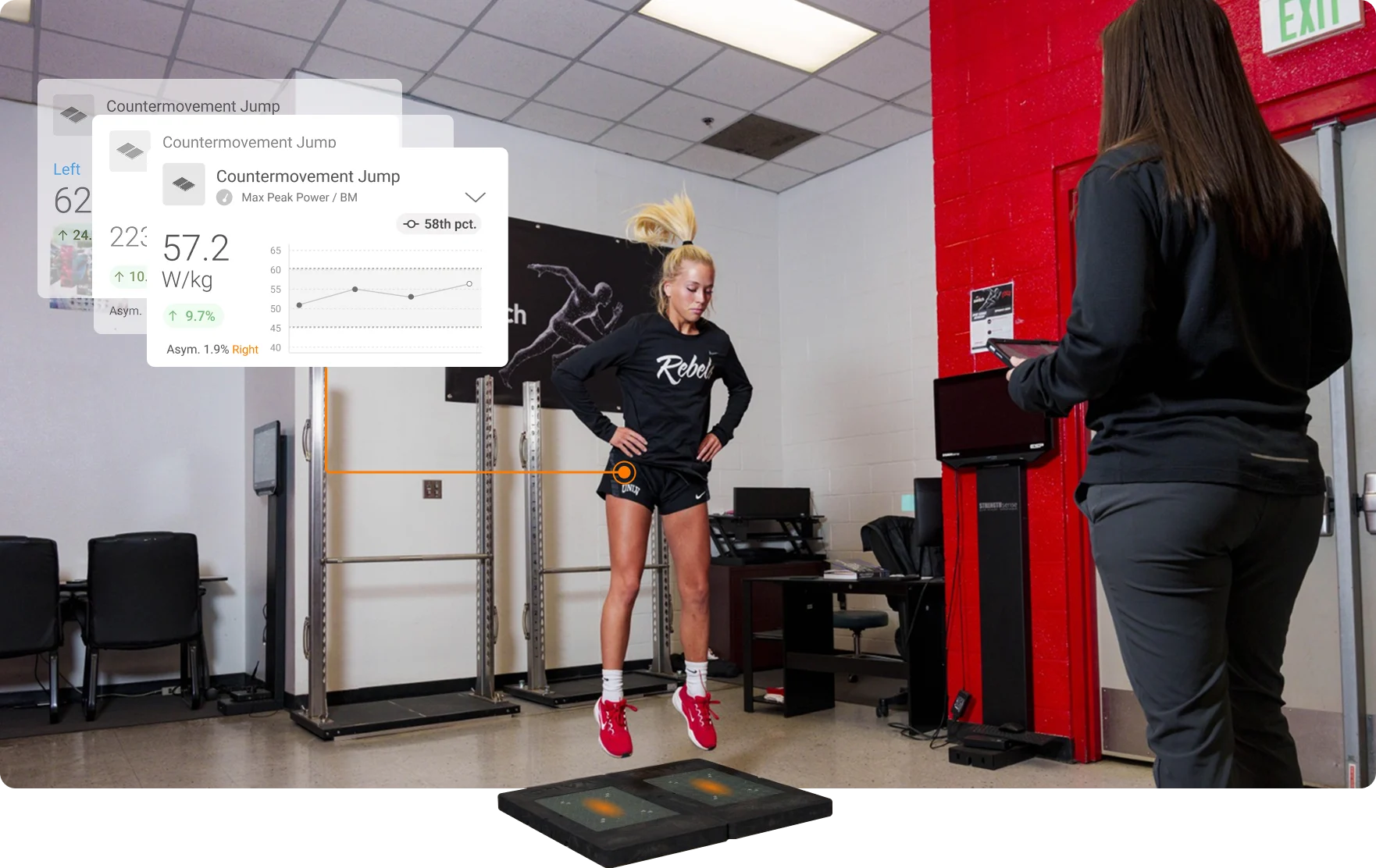

For instance, in most monitoring programs conducted by professional sports teams, the same weight is not given to subjective and objective data. A player reporting not feeling great will most likely get a tap on shoulder and be given a “warning” in the monitoring system; if, however, the player instead scores lower than usual at one of the “screening” tests (sit and reach, for instance), they will receive a lot more attention from the support staff, ranging from treatment in the physio room to specific warm-up in the gym. The measurable and local aspect of an “injury prevention test” reassures us; it makes us feel as if we can intervene and control the risks. That is why we overly rely on them and build our injury prevention protocols around local and easily measurable issues.

The global is much more intimidating. There is no easy test for emotional state to do before breakfast. Yes, most high performance departments use some kind of wellness questionnaires, but they fail to give players’ answers the credit they deserve and act on the information collected, whether because they don’t appreciate how critical subjective feelings are in injury prevention or because they just don’t know what to do.

When a player reports high stress in their morning wellness questionnaire, how many of us provide them with a stress reduction protocol? A few exercises, maybe tempo breathing and mental imagery, before asking about their stress level again and deciding how to approach the rest of the day with them, just as you would if it were a poor result at the hamstring mobility test? My guess is, not many of us.

Research on Psychological Factors and Injuries

Numerous studies, however, have highlighted the role of emotions in injuries. More than 30 years ago, researchers Williams and Andersen proposed the stress-injury model, putting psychological factors and emotions at the center of their injury prediction model. Many papers reinforcing such findings have since been published, with perhaps the most telling ones led by Ivarsson1 in 2008 and Angoorani2 in 2019.

The former reveals that the use of four factors can predict 23% of injuries sustained by elite soccer players throughout a season:

- Life event stress

- Anxiety

- Mistrust

- Negative coping (poor coachability and tendency to worry)

When one thinks about the complexity of the phenomenon that is the occurrence of an injury, 23% is a rather high number.

The researchers note as well that injury occurrences in soccer games happen within five minutes of a particular event that happened on the field, such as a red card, another player injury, or a goal, once again showing the undisputable role of emotions in risk of injury.

The latter has its own wow factor too. Studying injuries in relation to various predictive markers, researchers found that emotional intelligence is the single strongest predictor of injury in Iranian professional soccer players. Low ability to control emotions was linked to higher injury occurrences but not to fool plays and cards. The reasons for such relation, therefore, isn’t uncontrolled aggression that propels players into risky behaviors for themselves and others, resulting in more injuries.

The fact that it remains undiscovered how exactly emotions are able to increase the likelihood of someone getting hurt is fascinating. Many argue that it may be due to the effect of emotions on concentration; others point out that negative emotions, such as fear, anxiety, or anger, are accompanied by physiological changes that may well be the reason for subsequent injuries.

But the truth is probably elsewhere.

When we design a monitoring program, we prescribe tests and conduct investigations with the aim of gathering information on all the essential systems of the body. Integrating data in specific algorithms, the ultimate goal of a monitoring routine is to deliver an overview of a player’s state of health and readiness as close to the reality of their physiology as possible. There is no consensus on what to include in a monitoring routine, and the complexity of the human body makes it extremely difficult to come up with a recipe that delivers more than a gross—and mostly unreliable—estimation of one’s actual risk of injury. Emotions, however, could well be the natural way the human body has to make its own health and readiness monitoring report available to our conscious state… hence, why it seems these are decent indicators of injury risks.

Emotions could be the natural way for the human body to make its own health and readiness monitoring report available to our conscious state...making them decent indicators of injury risk. Share on XModern affective neuroscience stipulates that it isn’t just emotions affecting changes in physiology, but physiological changes affecting emotions.

The Emotional State of the Athlete

We are very used to the idea that emotions are triggered by external factors. We feel sad after losing a match, and if the last goal was a penalty scored thanks to a controversial referee call, we may even feel anger. However, if the loss is the result of poor performance, the locker room will instead be full of shame and regrets. We are happy if we break a personal record and are stressed when congested traffic makes us late to training.

We do understand that a certain emotion triggered by a specific event or environment is certainly accompanied by physiological changes: the excitement as we run on the pitch to compete in a final raises heart rate, blood flow, focus, and strength. The anxiety and pain we suffer as we exit the field due to an injury leaves us weak, cold, and unable to digest.

However, those sorts of emotions are rare, and how we feel the rest of time is a matter of enteroception, the body-to-brain afferent signaling, central processing, and neural and mental representation of internal bodily changes.

The interoceptive effect of the immune system on emotions is an obvious one. The feeling “sick” is very often reported by someone whose immune system is attacked by a virus or bacteria before any visible symptoms have yet occurred.

At a given moment, within a given context interpreted by one’s memory and belief, the brain uses concepts to make sense of internal sensations and give us an indication about how we fare as far as our chances of survival as well as the best strategy to deal with the current state of our internal environment. From a sore stomach, the brain builds an example of hunger, nausea, or distrust based on additional sources of information available, whether it is a memory, a visual clue, or the environmental conditions, for instance. From a higher-than-normal tension in a muscle, a player may feel annoyed, tired, in pain, or anxious depending on the area affected and history of injuries.

When negative emotions, such as a lack of motivation, increased perceived fatigue, or stress, are self-reported by an athlete in the absence of concurrent meaningful life event or performance-related factors, we have to interpret it as a clear warning sign sent from their physiology that something is standing in the way of homeostasis. What we attempt to reveal through the use of a monitoring routine is handed to us by the emotional state of the athlete. We just need to pay more attention. Too often, the conscientious strength and conditioning coach harasses the athlete who screened poorly on a mobility test but claims to be feeling good, while hastily clearing the athlete who screened normally despite reporting high stress or poor motivation.

What we attempt to reveal through the use of a monitoring routine is handed to us by the emotional state of the athlete. We just need to pay more attention. Share on XIn light of the elements discussed above, we could easily argue that it is time for the table to turn, for emotions to be regarded as a critical aspect of health and readiness monitoring demanding immediate further investigation instead of being looked at only in retrospective analysis.

Emotions and Motor Behaviors

Another aspect that might contribute to the decent connection between an analysis of emotions and injury prediction lies in the relationship between emotions and motor behaviors. Indeed, it is well documented that each emotion can affect movement patterns.

Think about the blatant difference in attitudes between players who won and those who lost just after the referee blows the final whistle. On one side of the pitch, chests are held high, hands fly into the air, smiles illuminate faces, and the energy level is so high that some players jump and run around. On the other side, shoulders are rolled in, upper bodies carved up, and hands hiding faces. Energy is so low that some players lie on the ground or kneel, head on the ground. Still, both teams just played the same number of minutes of the same game, and their GPS and heart rate data are not so different.

If the physical demand of the game can’t justify such a discrepancy in motor behaviors, what we are witnessing is the power of emotions. As discussed before, when feeling under threat, the body will always focus on protecting the front, where the most vital organs are situated. The fighter assaulted, trying to ensure his survival, displays a posture and motor behaviors very similar to the anxious and depressed office worker taking their 7 p.m. commute after yet another day of conflicting and disempowering interactions. A forward-bent torso, shoulder rolled in front, chin that tends to tuck, looking at their feet: innate protective motor behavioral changes that come with negative emotions such as anxiety, fear, sadness, or stress all encourage withdrawal and are less than optimal to engage in highly demanding or explosive physical activity.

If a body under threat has already chosen withdrawal as the survival strategy and is then forced to engage in an activity that represents an additional threat, the motor behavior displayed won’t change to suit the demand of that activity. Actually, the reverse: it will worsen. A player taking part in an opposed training or a match while depressed will display motor behaviors that prevent them from optimally taking on information (looking down, carved-up posture), which can increase their chances of putting themselves in a situation prone to injury.

Put an anxious player through a speed session, and muscles located at the front of the body will tighten even more, cortisol will rise further, and eventually, some tissue located at the back of the body will end up as a casualty.

Monitoring routines and other injury prevention programs need to include more serious emotional state assessments and clear interventions. Share on XMonitoring routines and other injury prevention programs need to include more serious emotional state assessments and clear interventions.

Finding the Right Scale and Solutions

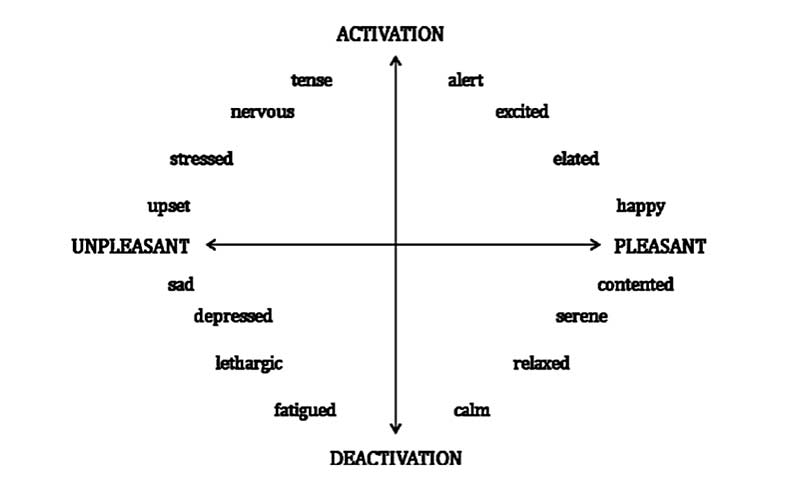

First, a question or two asking a player to rate their stress level or motivation on a scale from one to five as part of the daily wellness questionnaire isn’t enough. There is much more to emotions than just stress and motivation. A much better assessment is to ask a player to select one or more words from among a selection of emotional states to describe how they feel today and provide them with an intensity cursor or color code associated with the words chosen in order to get information on the intensity of those emotions.

A continuum from activation to deactivation as well as pleasant to unpleasant should be used to better understand what a player needs to be ready for training on that day.

Emotions present in the high activation and pleasant quadrant are the ones associated with optimal readiness to train, whereas those of the unpleasant, deactivated quadrant describe an injury-prone state. A “low motivation” reported on the usual wellness questionnaire could mean the player feels too relaxed or too nervous or again lethargic, which are all very different states. A too-relaxed athlete can easily be moved to an excited state with some priming words from the coach and activation work prior to training, whereas a lethargic player needs to be first moved to a relaxed state through the use of some specific techniques (see below) before they can eventually be “primed.” Hence, the need for a more thorough way of assessing the emotional state.

With such an emotional state assessment, the aim of a player pre-training routine can be first directed toward “emotional” priming. Indeed, one of the beauties of emotions is that if they are a representation of our internal environment and health while being able to affect motor behaviors, they can in turn be affected by a change of physiology or posture.

Therefore, the emotional priming process could look like this:

- Step 1: Assess dominant emotion as part of a morning monitoring routine through the use of the quadratic model.

- Step 2: If needed, go through a specific protocol designed to shift a player’s reported dominant emotion from unpleasant to pleasant as a part of individual pre-training preparation time.

- Step 3: If needed, go through a specific protocol designed to raise the activation level of the dominant positive emotion as a part of the pre-training activation slot.

Shifting from an unpleasant-activated to a pleasant-activated state is possible using a variety of techniques, preferably facilitated and supervised by the team psychologist or mental coach. Those include:

- Positive mental imagery: The player consciously and purposefully closes their eyes and visualizes themselves succeeding at the upcoming training session. Five minutes of visualization can create a strong positive change.

- Reframing: The player expresses verbally or by writing what is most likely the source of the negative emotion—and then consciously and purposefully reframes the events leading to those emotions differently, using empowering and positive words only. Reframing has been shown to induce change of emotional state.

- Postural adjustments: This concept is used in behavioral therapy, when patients are encouraged to smile as a behavioral intervention to help them elevate their mood, even when the smile is initially artificial. The activation of the facial muscles into an expression associated with happiness evokes or enhances this associated emotion, leading to the improvement in mood.

- Equally, a player feeling stressed or anxious can be prescribed a series of activation exercises directed toward changing the motor behaviors associated with such negative emotions. For instance, pull-throughs and other chest openers can temporarily reverse rolled-in shoulders and a bent-over torso. Face pulls and Turkish get-ups can be used to keep the head erect, and good mornings or bear hugs hold forces to straighten the back.

- By changing their posture through movement, the athlete can experience a shift in their emotion. This mechanism is likely based on proprioceptive input to the brain regarding the current state of the body’s muscle activation pattern and joint configuration and existing associations in the brain between certain proprioceptive input and specific emotions.

Shifting from an unpleasant-deactivated to pleasant-deactivated state is possible using a variety of relaxation exercises such as:

- Controlled diaphragmatic breathing: The diaphragm has multiple physiological roles. The phrenic nerve that innervates the diaphragm’s functions has a connection with the vagus nerve, which can affect the whole body system. Diaphragmatic motion in breathing directly and indirectly affects the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems and influences motor nerve activities. Diaphragmatic breathing is defined as breathing in slowly and deeply through the nose using the diaphragm with a minimum movement of the chest in a supine position with one hand placed on the chest and the other on the belly, inhaling and exhaling for approximately six seconds, respectively.

- One study showed improvement in the biomarkers of respiratory rate and salivary cortisol levels, one showed improvement in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and one study showed an improvement in the stress subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) after implementation of a diaphragmatic breathing intervention. Five minutes of diaphragmatic breathing can therefore change some pretty strong physiological markers of stress and induce a shift in emotional state.

- Progressive muscle relaxation: This anxiety-reduction technique first introduced by American physician Edmund Jacobson in the 1930s involves alternating 15 seconds of tension and 30 seconds of relaxation in all of the body’s major muscle groups. Research shows that such quick relaxation exercise can decrease cortisol and perceived anxiety, making it an easy way to help a player move away from a negative emotion to a more positive one.

Raising the level of activation of a pleasant emotion is a relatively easy task. For most strength and conditioning coaches, this is what they more or less consciously attempt to do when programming “activation” work pre-training. A well-designed warm-up (more on this in the previously published article on warm-up strategies) using sensory and mental activation techniques will likely be enough to ensure that a calm player becomes alert and a relaxed one, excited.

Going straight to the pre-activation and warm-up with a player reporting unpleasant emotions can increase injury and poor performance risks. Emotions of the unpleasant-activated quadrant, such as nervousness or anger, are conducive to stiffer muscles, high aggression, and lower self-control in duels and contacts, as well as a limited ability to learn and memorize. Hence, it’s important to try to shift a player’s emotional state from unpleasant to pleasant before raising the level of activation.

The above strategies were aimed at reducing the potential negative effect of unpleasant emotions pre-training by inducing temporary and superficial changes. When a player reports a negative emotional state for several consecutive days, or when the individual displays a strong tendency to feel unpleasant emotions, then quick short-term fixes won’t be enough to diminish their injury risk. In this situation, it is necessary to increase daily contact time with the player to understand better what may cause the tenacious and unwanted emotion and organize regular meetings between them and the team psychologist or mental coach to develop better coping mechanisms.

Emotions and the Rehabilitation Process

Understanding the power of emotions and their role in injury risk can help us finally rehabilitate the human body. Usually, injury prevention models are built on the assumption that the body is quick to fail us and, in the end, not that smart.

Understanding the power of emotions and their role in injury risk can help us finally rehabilitate the human body. Share on XInjury prevention programs largely focus on correcting and treating the imperfect body. When an injury happens, we are quick to point out “poor movement technique” or “training load.” Models are today built to shame the poor human body, claiming it’s unable to adapt to a training load’s variation. All this gives us an image of a fragile body to be protected from all the threats thrown at it. Sprinting! Lifting heavy! Variability in volume of training! Weather conditions! And more.

This vision is the result of the still-dominant theory of the brain versus body dichotomy: the brain constantly needing to supervise and boss around a body that isn’t much more than a machine. Such a view of our physiology is obsolete, and decades of sciences have shown that no separation or hierarchy exists between the body and the brain. Unconsciously, our body and brain work together relentlessly to ensure our survival.

We may accuse our body of not being made to be as fast, as powerful, or as agile with a ball that we want it to be, but accusing it of fragility is nonsense. The human body is a master healer, able to fight numerous threats all the time, bacteria and viruses, compression and tension, heat and cold.… When non-contact injury occurs, it isn’t because our body gave up on us, but because the strategy chosen to ensure that more vital structures were preserved and our survival was guaranteed resulted in damage to less important tissues.

Nothing ever happens by mistake or chance in the body. When we accept the hard fact that pain and injuries are not system failures or punishments but protective mechanisms, and that the strategies employed by the body and brain to ensure survival are under no obligation to make sense to our conscious selves, it can free us from thinking that the enemy lies within us.

When we accept the hard fact that pain and injuries are not system failures or punishments but protective mechanisms, it can free us from thinking that the enemy lies within us. Share on XSo here we are.

If non-contact injuries are for the most part collateral nuisances of unconscious protective strategies, preventing injuries requires that we decrease the amount and intensity of threats perceived by an athlete’s body and brain. If we currently do a decent job at monitoring visible and easily controllable sources of perceived threat, such as training load or mechanical and bio-energetic fatigue, we do however need to make more of an effort to include less visible and controllable—but nonetheless critical—sources of perceived threat, such as a negative emotional state and psychological stress.

Four simple principles can easily be implemented in training programming and monitoring to address those.

- In a high performance plan, training and recovery are balanced. The same approach needs to be implemented for emotional states. Activities or environments that induce unpleasant-activated emotions should be immediately balanced by activities or environments promoting pleasant-deactivated emotions. A tough loss during an important game on Saturday night would be better followed on Sunday with recovery at the beach or SPA and a team barbecue as opposed to individual reviews, physical top-ups, and a team meeting.

- During scheduling of training, travels, and other commitments, a real emphasis should be put on avoiding cumulative unpleasant emotion-prone activities. A clear example is the quite common succession of a physically stressful and anxiety-inducing physical activity (game or hard training session), a psychologically stressful and anxiety-inducing activity (individual review), and an environmentally stressful and anxiety-inducing event (travel, press conference).

- Each player has a limited and finite negative emotion bucket that, if full, can trigger a strong survival response—the kind that does not care too much about creating a muscle injury in the process. Making sure that we do not fill that bucket too much on a daily basis by alternating stressful, exhausting, confrontational activities with calm, relaxed, safe ones is definitely a great place to start. Following a similar thought pattern as the one used to define and plan training loads, emotional load should be considered. “Emotionally taxing” events such as matches, travels, tough physical sessions, tactical meetings, etc. and “emotionally boosting” ones such as social time and recovery activities must be kept balanced.

- Language used may well have some influence on preventing injuries. Many studies have shown that negative words unconsciously prime negative emotions and positive language leads to positive states. Sometimes, as strength and conditioning coaches, we pride ourselves so much on hard work that we speak to our athletes in a negatively charged way. “No pain, no gain” is written on the gym wall, and we enjoy finishing our session brief with “this is going to hurt guys” or “it’s going to burn.” We need to understand that the more we talk about pain, about being uncomfortable and tough, the more we prime our players to feel pain, anxiety, and fear.

- As the unconscious does not care about where the threat comes from, language alone can contribute to trigger a survival response, increasing injury risks. It is possible to drive a hard work culture of training with positive words. “Challenging” instead of “painful,” “rewarding” instead of “tough,” or again “transforming energy” and not “emptying the tank.”

- The art of resting: when in doubt, give the player a break. The best way we can help the body do its job of healer is to give athletes some rest. In professional sports, doing nothing or prescribing rest is seen as weakness or incompetence. Support staff should always be ready to pull some sort of treatment, exercise, or technology out of the hat of “the evidence-based best practices.” Preventing injuries isn’t about doing more all the time: more testing, more data analysis, more “preventive work.” Oftentimes, it is about recognizing when we need to gain some time by pulling a player out of training until we figure out what is really going on with them.

- Being aware of the impact of emotional state on injury risk, an athlete reporting a negative emotional state for a few consecutive days would most likely benefit from a couple days off and a meeting with the team psychologist or mental coach in an attempt to empty a little of their stress bucket instead of continuing to push them through the planned training loads. A day or two off will always be a better option than the amount of time on the sideline that a muscular injury would require.

- Be mindful of negative people. Emotion is a significant predictor of injury risks and can spread throughout a group like pollen borne on wind. This emotional contagion often goes unnoticed and operates via our innate tendency to mimic the emotions of other people. A recent study showed that cartoons were rated funnier if participants were first presented with a picture of a smiling face. Simply being exposed to the non-verbal behaviors of others is enough to trigger a similar emotional experience, be it positive or negative.

- In group settings, social rules influence thinking and behavior, and a club culture has the ability to increase or decrease injury risks. It is critical to put rules and behavioral expectations in place that reinforce positive emotions. Social rules may also develop based on the types of beliefs, attitudes, and emotions held by particular team members.

- Alarmingly, research has shown that the behaviors of just one person can set these rules. In one study, 94 business undergraduates were observed as they took part in a group discussion. Unknown to the participants, one person was actually a plant tasked by the experimenters to purposefully display negative emotions in the group setting. Overall group performance and cooperation significantly decreased because of this negative influence.

- With this evidence in mind, it is simple to understand that negative emotions cannot be left freely expressed and demonstrated within the team environment, or sooner or later it will have an impact on the team’s health and readiness. Poor results, long working hours, or divergences of philosophies can be a burden at times for support staff, and sometimes frustration, anxiety linked to job security, or near exhaustion can transpire in the way we behave, talk, or look at the office.

- It is, of course, impossible to go through a full season of competitive sport feeling fresh and amazing; we have to keep in mind that personally giving in to negative emotions will impact athletes and other staff members around us. No matter how difficult it may be, a real effort to be positive around other team members goes a long way in contributing to lower injury occurrences and better team performances.

It is also the responsibility of leaders within the organization to ensure that the wellness and readiness of the staff members are monitored and optimized, exactly as it is done with players. Support staff can do everything and beyond to keep the players happy, healthy, and performing on the pitch week-in and week-out. However, if it comes at the expense of their own welfare, transforming them into zombies or frustrated, angry, and overworked victims, they will contribute to an increased injury risk for their athletes despite all their good work.

Preventing injury is much more than correcting poor movement strategies, developing strength, and monitoring training loads. It is time we accept the role of less “controllable” factors, and especially the power of emotions, and do our best to get our athletes out of a subconscious survival state.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Ivarsson, A. (2008). “Psychological Predictors of Sport Injuries among Soccer Players.”

2. Angoorani, H., Najafi, S., Sobouti, B., Zarei, M., and Nejati, P. “The Association of Emotional Intelligence with Sport Injuries and Receiving Penalty Cards Among Iranian Professional Soccer Players.” Asian Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;11(1). 10.5812/asjsm.97321.

3. Hartel, C. “How to build a healthy emotional culture and avoid a toxic culture.” Research Companion to Emotion in Organizations. 2008:575–588. 10.4337/9781848443778.00049.

4. Hackfort, D. and Kleinert, J. “Research on sport injury development: Former and future approaches from an action theory perspective.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2011;5(4). 10.1080/1612197X.2007.9671839.