Coaches and athletes are always looking for better ways to train, but leaving out the mindset from the equation is foolish. This article shares six essential mental areas that help good athletes become great, and the great athletes legendary. If you were to study some of the greatest to ever perform in sports, the commonalities are pretty stark. I will share the six areas of potential and break down why they are important, how they work, and what you need to do to apply those mental skills.

I have spent years studying and working with some of the best professional athletes and learned from the works of pioneering experts in the field. In this crash course, I share the very best of what I use with my own athletes so you can apply them directly. You may choose to use one or plan out a road map to use all of them with your athletes or yourself. I have used the techniques for years with our athletes and the changes are transformative, sustainable, and of course ethical. You don’t have to be an athlete or train athletes though, as the general demands of everyday life can benefit from the recommendations below.

Learn to Apply Triggers

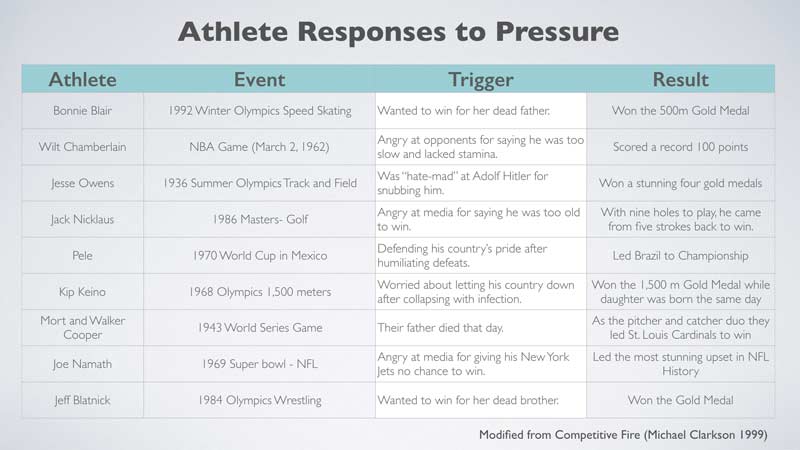

If you’re a high-level coach, then you’ve experienced the athlete who just doesn’t give you enough. You know—the individual who can give so much more but doesn’t. We all look to the athlete instead of the coach. Yes, getting an athlete to buy in or lock in is tough, but if you have triggers you can override that entire phenomenon itself.

Triggers are the mental skills that allow a performer to tap into their deep motivational roots. Triggers can’t be seen—they’re internally driven—but they can be experiences. Share on XTriggers are the mental skills that allow a performer to tap into their deep motivational roots. Triggers can’t be seen—they’re internally driven—but they can be experienced. It’s that switch we see being turned on, where an athlete’s body language, demeanor, and intensity shifts from house cat to tiger; where the athlete proceeds to dominate the task at hand, attaining the desired results. Contrary to current day beliefs, like the classic line from Rocky Balboa goes, the (performance) world really isn’t all sunshine and rainbows.

Coaches who work with high performers know that it’s a world of aggression, cruelty, and ego. That’s why triggers tap into controlled anger or aggression versus the other fluff; research shows that it’s more beneficial to tap into anger and aggression when you can control it. They enhance performances when used in the right ways and ensure that no results are left on the table.

In 2005, Robazza and Bortoli proved that tapping into controlled aggression led to better performances when they studied a group of rugby players and looked to anger as the driving motivational factor. They found that a calm, cold, and controlled aggression brings out a stronger level of effort in performances. Even some of the world’s best athletes have been tapping into triggers for ages: Michael Jordan proving his high school coach wrong; Kobe Bryant playing Journey’s “Don’t Stop, Believing” over and over again in the offseason when he trained; Tom Brady getting back to work right after the Patriots were eliminated this season so he could start preparing for the next season (although he’s just declared next season will be with Tampa Bay and not New England).

There is, however, both an art and a science to weaponizing triggers; it isn’t just a matter of getting someone angry or annoyed. Instead, this is about understanding how to guide an athlete by using these triggers effectively while calling on a mixture of adrenaline and dopamine. It doesn’t matter if it’s in a weight room with 300 pounds over their face or during a performance with 40,000 fans watching—you must master the art and science of tapping into triggers or you’ll be allowing your athletes to walk away while leaving results on the table.

Know When to Use Dark Triggers

I’m sure you’ve seen the classic scenario where a coach calls out a player and challenges them, and then the player responds and dominates the task at hand. Or maybe you’ve experienced someone calling you out, challenging you as a professional or a person, and you’ve responded flawlessly. You feel the rush of adrenaline through your blood and right after that momentary rush, you get so focused on the end result that nothing can stop you.

Dark triggers are meant to be used for momentary surges of energy; the art behind tapping into this trigger is that you let your anger fuel your intentions of proving someone, or something, wrong. It’s being able to temporarily call on a moment of pain to spike adrenaline so you can sprint to the end result. It’s brief, temporary, and highly impactful.

Sigmund Freud has been explaining this to us since 1895 with his Pleasure Principle: the mind seeks pleasure and avoids pain. When you control the bouts of anger that you’re about to unleash on a person you want to prove wrong, you experience positive performance results. In his book Endure, Alex Hutchinson highlights the importance of being able to tap into this deep, driving motivation: He found that in the final, sprint-like moments of a marathon, the brain is responsible for overcoming limitations. And they’re not just effective in marathons either.

Look at the great Michael Jordan: All it took was for the Grizzlies’ Darrick Martin to trash talk Jordan in the fourth quarter. Jordan pushed his dark triggers, or that “prove you wrong” scenario, the adrenaline was released, and he went off. Going into the fourth quarter he had 10 points; he finished the game with 29. It’s that “gun to the head” mentality we hear about so often—you just better make sure you choose the right weapon. If you don’t master the skill of tapping into dark triggers, then you won’t be seeing your athlete’s truest potential.

Coaches, I’ll warn you now: If you overstimulate an athlete’s dark triggers, you run the risk of burning out your athlete. You should only be using this weapon when you need to increase the adrenaline—most likely at the start or end of a performance or during a time of despair. In short, don’t overuse these weapons. There’s a balancing act that comes into play at this point; what do you do once you’ve pressed these dark triggers? Adrenaline management is the key, and light triggers are the tool that’ll help you achieve this.

Create a Steady Burn with Light Triggers

Light triggers still tap into anger and aggression, but the intentions are to prove someone right; you’re fighting to get the result for something that brings you fulfillment. Or, in short, you’re purposely filling the blood with dopamine to manage the adrenaline by focusing on pleasure.

Again, this goes back to 1895 and Sigmund Freud—the mind seeks pleasure. And if the mind prefers pleasure over pain, then we have to be able to play to this pleasure more than we do the pain. Dark triggers are meant to spark someone when the fire starts going out, but once that fire’s lit, we have to keep adding wood (imagine what would happen if we just kept trying to spark it). When you control your anger and guide it toward making something good happen, then you gain control over a situation. Think, a simple shift in perception of “revenge with violence,” to “revenge with results,” can change an entire performance outcome. One most likely causes you to get ejected from a game, while the other allows you to feel satisfaction from attaining results.

How many athletes have you heard of who get into the daily grind so they can provide a better life for their families back home, or who have had a loved one pass away and now they want to achieve success in their honor? These are light triggers—there’s a guided anger, a “stop at nothing” mentality, that takes over, where these individuals fight for the fulfillment of proving something right or supporting those they love. That’s when the sunshine and rainbows can come back and when you should be tapping into these light triggers.

Light triggers are a guided anger, a *stop at nothing* mentality that takes over, leading individuals to fight to prove something right or support those they love, says @mattcaldaroni. Share on XAnd, again, the science proves that fulfillment is crucial for long-term high performances. In 2017, a study showcased the correlation between job enjoyment and reduced levels of burnout, with the major indicator for burnout being a lack of fulfillment in experienced results (Demerouti et al). Or, in short, working for something without a cause; a lack of dopamine when experiencing results.

The same thing happens when you only depend on dark triggers: If there’s too much adrenaline and not enough dopamine, then you’re playing with fire. You need to have a mix of dopamine to manage the adrenaline. If you’re in a stadium with 40,000 people and the adrenaline is surging, how do you control it? In a heated moment of anger when someone gets in your grill, how do you keep controlled? In a moment where you broke through a PR on your last set, and now you need to finish the workout, how do you stay high and not drop off? Light triggers.

The key to all of this is learning when to turn these triggers on, and when to shut them down. That’s when the alter ego comes into play.

Design and Cultivate the Alter Ego

I’m sure you’ve seen or heard about the transformation an athlete makes when they walk into their performance environment; their whole demeanor changes. They put on their mask and become a completely different person than who they are out of performance. The easygoing individual they were at home now becomes a cutthroat high-level performer. And as I said before, we need this in performance, because it’s a mean world of high performance. This is the power of an alter ego: It allows you to put on your mask and become a relentless individual who taps into their triggers and stops at nothing, or gets into what is known as “the Zone.”

The crazy part about it is that a form of the alter ego is not new, by any means. In the 1960s, when Russian psychologists used various mechanisms on the Russian and East German Olympic squads, they just called it a co-personality. In the book Red Gold: Peak Performance Techniques of the Russian and East German Olympic Victors, Grigori Raiport talks about the various mechanisms that were used to create the co-personalities of the athletes. They included manipulating the athlete’s routines, motivations, attitudes, and relationships, ultimately creating this person who was more aggressive when they were in performance. In short, they built an alter ego for the athlete that they fully embodied when they were in performance.

This concept of an alter ego wasn’t just used by the Russian and East German Olympic teams either. The infamous Kobe Bryant, or rather the Black Mamba we all knew him as, has alter ego written all over it. It’s like Michael Jordan turning into Air Jordan, or Brian Dawkins turning into the X-Factor. Alter egos are a tool we must capitalize on, otherwise you’ll only see a fraction of the results with your athletes in performance. It’s knowing when to put your mask on and become the person that your team needs you to be, both in and out of performance. I’m sure you’ve heard the stories of the Black Mamba barking at his teammates in the gym for cutting corners, but then Kobe Bryant taking them out to dinner afterward and being their friend. Every athlete needs this alter ego, and if you haven’t prescribed it to them yet or taught them what it is and how to use it, then you’re missing out on their best performances.

Master the Quiet Zone

But what about shutting it down; how do we ensure that the alter ego doesn’t take over? If you’ve been around high performers, then you’ve realized that they all have specific people, places, and activities that they like to engage with that allows them to disconnect. Or, they visit their quiet zone.

Whenever an athlete is visiting their quiet zone, be it at the family dinner, watching a movie with their loved ones, or people-watching at a restaurant, they know that the alter ego doesn’t belong there. Or, at least, they should; if you’re not conditioning your athlete to shut it down when they’re out of performance, then you’re running the risk of burnout. If you don’t have a controlled quiet zone, then you’re running the risk of burnout.

It’s evident that you need to have some sort of obsession if you truly want to do extraordinary things, but too much of anything is never a good thing. There have been countless studies that show the importance behind disconnecting and why it’s crucial for performance; in one study done by Smith et al., researchers found that mental fatigue impaired soccer-specific physical and technical performances. Too much is never a good thing, and the current notion being pushed that “taking a day off is a weakness” is actually the weakness itself (ironically). Both the body and mind need a break from all the adrenaline and dopamine surges; simply put, we need balance.

Both the body and mind need a break from all the adrenaline and dopamine surges. Simply put, we need balance, says @mattcaldaroni. Share on XFrom recent studies, one day per week of stepping completely away from competition does the trick. What you do on that off day matters though: How many times have you taken a step back from performance and gone out with a group of friends, only to realize there was no real “me time” happening at all? There was no real personal reflection that could occur. Then, you come back to performance feeling even worse than before the break! Not with a quiet zone, though; when you have this mental tool primed, scheduled, and loaded, the step back becomes more effective. And if you really want to enhance it, then you have to take on a dopamine fast.

Remember the Dopamine Break

You have to be able to step away from the adrenaline if you’re going to be a long-term high performer. This goes hand in hand with visiting the quiet zone; you have to be able to reset and recharge. The adrenal glands have to rest and recover, or they’ll be shot. And if you’ve ever experienced uncharacteristic anxiety, rapid heartbeat, elevated blood pressure, or excessive sweating and palpitations, especially after adrenaline-filled environments, then you’ve most likely experienced the side effects of too much adrenaline.

In today’s world, where athletes are constantly at the demand of social media and social channels or other addictive behaviors like recreational drug and alcohol use, video gaming, etc., they’re dually combatting the adrenaline surges mixed with overstimulated dopamine sensations. Study after study shows the correlation between too much dopamine and issues like ADHD, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, depression, bipolar disorders, and addiction. Mix that with a high-strung, adrenaline-surging athlete, and we’ve got the perfect storm brewing for an athletic disaster.

This isn’t something we haven’t known, either. In 2017, the book Unplugged, by Brian MacKenzie, Dr. Andy Galpin, and Phil White, warned us of this overstimulation by dopamine and the issues it could cause. And let’s get this straight—I’m not talking about “fasting” from dopamine; I’m talking about stepping away from the social demands of the world and just resetting for a day. It’s a matter of abstaining for just 24 hours from all activities that create manmade surges of dopamine and reflecting.

This is why you see athletes, especially Italian soccer players, take mini vacations during their Christmas breaks; whether they know it or not, they’re getting away from the social world. Or why the great Sidney Crosby doesn’t have social media; one of the most marketable athletes in the world makes it a point to step away from the social game.

However, despite all of this, we still haven’t taken action against it. We still haven’t made a point to schedule dopamine reset days. If we’re going to demand that our athletes to be constantly on a high in performance, then we have to know the mechanisms to step back and reset so that we can achieve a long-term balance. And if you haven’t been paying attention to this, or haven’t taken this on, then you’re cutting performances short—the science shows it.

It’s evident that if you haven’t been tapping into these mental gems, then you’re doing your athletes a disservice. These have literally been around for decades. You have to tap into them.

Winners Find a Way and Are Prepared

Life is not fair. The good news is that you can control a lot more than you know. While everyone is scrambling for bodyweight exercises and home workouts, you should consider the gift you have between your ears. If you really want it, the core essentials of training should be enough to get most of the results you need. It’s important to be the coach or athlete who is skilled at mentally being ready for anything, including a lockdown or quarantine.

It’s important to be the coach or athlete who is skilled at mentally being ready for anything, including a lockdown or quarantine, says @mattcaldaroni. Share on XThe month of March is forever etched in history as the time most of the world came to a screeching halt, but those who are resilient march forward and find a way. You don’t need much to be prepared for the return to a new normal, just a plan and the confidence in yourself to make your goals become reality. Stop everything and work with a coach or mentor who is beyond a “sets and reps” type of expert—work with a professional who is trained and skilled in preparing the mind for battle.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Demerouti, E., Veldhuis, W., Coombes, C., and Hunter, R. “Burnout among pilots: psychosocial factors related to happiness and performance at simulator training.” Ergonomics and Human Factors in Aviation. 2017;62(2):233-245.

Rathschlag, M. and Memmert, D. “The Influence of Self-Generated Emotions on Physical Performance: An Investigation of Happiness, Anger, Anxiety, and Sadness.” Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 2013;35:197-210.

Robazza, C. and Bortoli, L. “Perceived impact of anger and anxiety on sporting performance in rugby players.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2007;8:875-896. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.07.005

Smith, M.R., Marcora, S.M., and Coutts, A.J. “Mental Fatigue Impairs Intermittent Running Performance.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2015;47(8):1682-1690. doi: 10.1249/MSS.000000000000059

Wang, J.C.K. and Biddle, S.J.H. “Intrinsic Motivation towards Sports in Singaporean Students: The Role of Sport Ability Beliefs.” Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8(5): 515-523. SAGE Publications. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F13591053030085004

Woodman, T., Davis, P.A., Hardy, L., Callow, N., Glasscock, I., and& Yuill-Proctor, J. “Emotions and Sport Performance: An Exploration of Happiness, Hope, and Anger.” Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 2009;31:169-188.

How do I overcome failure when I keep doing it over and over again and not learn from it.