[mashshare]

Everyone has another side in performance that allows them to turn up the aggression, increase their intensity, and lock into the task at hand. Everyone has the ability to flip the switch and become “a beast” when they step into their performance environment. It’s called the alter ego—everyone has one, yet very few people tap into it. It’s a place that allows you to break free of any self-doubt and limitations and completely dominate the task at hand.

It’s simple: As a repercussion of not tapping into this mental skill, you leave results on the table. Think about how many athletes you have on your roster who you know can bring more, but don’t. How many athletes do you know who have this amazing side to themselves that they don’t utilize?

As a repercussion of not tapping into the mental skill known as the alter ego, you leave results on the table, says @mattcaldaroni. Share on XIf you’re a strength coach who’s not helping your athletes tap into this mental skill, then you’re doing them a disservice. In this article, I’m going to teach you about the alter ego and how you can help your athletes truly empty the tank, be fully locked in, and dominate the task at hand.

Kobe Bryant’s Alter Ego

If you’re involved in sports at any level, then you’ve seen the power of the alter ego fully activated and utilized by one of the world’s most iconic athletes: Kobe Bryant, aka, the Black Mamba. While the majority of people thought it was just a good marketing tool, the truth is—as Kobe stated in his documentary “Muse”—he utilized his alter ego as a mental skill in performance.

It gave him the ability to turn off his personal life and the biosocial behaviors that came with it and turn on his true competitive nature in his professional life. It allowed him to be an easygoing guy outside of performance and a dominant force within performance. It allowed him to raise his standards and comply with what he was given while raising the standards of others around him as well. It made him a pleasure to work with in the weight room and turned him into an iconic individual in the sport of basketball.

He was able to take control and not just “think different” or focus on his breathing, like the majority of the “mental gurus” suggest, but instead fully embody a different being on the court. He dropped the personal drama, blocked out the noise, locked into the task at hand, and turned up the aggression and intensity. From 2004 on, Kobe didn’t stop dominating: At home he was Kobe Bryant, the soft, easygoing father, but at basketball he was the aggressive and intense Black Mamba—the leader of L.A.

I know that you’ve had athletes similar to Kobe before; ones who deal with personal issues at home and have to be able to block out the noise. Or ones who are naturally softer as a person and don’t often push their limits. How about the ones on the opposite end of the spectrum—the ones who are too engaged and can’t turn it off, often burning out, or ones who are too aggressive and out of control?

When you utilize the alter ego, you’re able to have your athletes push buttons that they didn’t even realize they had, says @mattcaldaroni. Share on XThe brilliance of this coaching tool is that it allows you to eliminate both of these issues within the athletes you work with; when you utilize the alter ego, you’re able to have your athletes push buttons that they didn’t even realize they had. You’re able to get them to lock into what you’re coaching them on, bring the most effort possible, and retain it when they’re finished by keeping them hungry for the next session. If you’re not utilizing the alter ego in your coaching, then you’re not truly serving the athletes you work with.

What Is the Alter Ego?

An alter ego is more than just a “change/separation of thinking,” and it’s more than just a self-talk or deep breathing mechanism. Truth be told, these “block out the noise” techniques commonly referred to aren’t extremely effective. Everyone who works with elite-level athletes knows that there’s too much going on for the athlete to be consciously thinking about “blocking things out.” It has to be instinctive; there has to be a tool that allows the athlete to stay locked in on one thing and focus on the task at hand, bringing the most compliance and effort during the session, and allowing them to retain after the session.

An alter ego does just that. It’s about embodying another being that gets turned on during performance, allowing an individual to drop all the noise, self-doubt, and negativity in performance and dominate the task at hand. It allows them to become the person who their team or performance needs them to be and get the results consistently. There’s no need to “cancel out thinking”; when you fully commit to identifying as a different being, you take on the characteristics of that individual. There’s no more thinking. Instead, there’s just taking action, which is ultimately what we want our athletes to do.

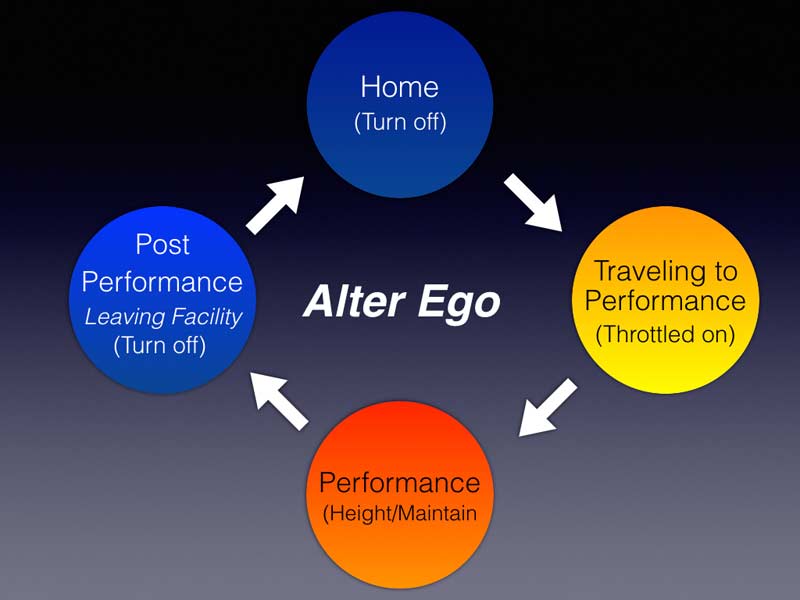

An alter ego, in its literal term, is a person’s secondary or alternative personality; it’s who they are in their performance environment. It’s who they choose to be when they’re performing at their sport. It contains mental, physical, and social traits that are ignited internally as a reaction to their environment. It’s turned on during performance but turned off after it. Some athletes choose to be an animal like Kobe did, while others choose to be a superhero or heightened version of themselves like Brian Dawkins, or “the X-Factor.” In short, they identify as something more aggressive that allows them to fully comply with the task at hand, bringing a strong effort to whatever it is that they have to do.

Now here’s the most important part: your job as a strength coach is not to help your players find their alter ego—that’s my job as a resilience coach. Instead, your job is to pull this alter ego out of them; to help your athlete find that extra gear by creating an environment that fosters the alter ego to come out and communicating in ways that allows the individual to internally trigger themselves. If you want to get the most out of your athletes, if you truly want to serve them and take them to the next level, then you must add the alter ego into your coaching toolbox.

Why Every Athlete Needs an Alter Ego

Plain and simple: If you’re a strength and conditioning coach who’s not helping your athlete build their alter ego, then you’re leaving a lot on the table and forgetting about some of your responsibilities. The motivational aspect of strength coaching is a true art that I’m frequently asked to consult on. It’s a sticky topic with a lot of grey areas, and I always suggest utilizing the alter ego for this exact reason.

When you have a framework with proven results that allows you to play to the needs of both the individual and the group, then you’re taking care of all of your responsibilities. If you’re not using the alter ego, then you’re not giving your athletes the best chance to succeed. And more importantly, you’re not seeing their true competitive nature.

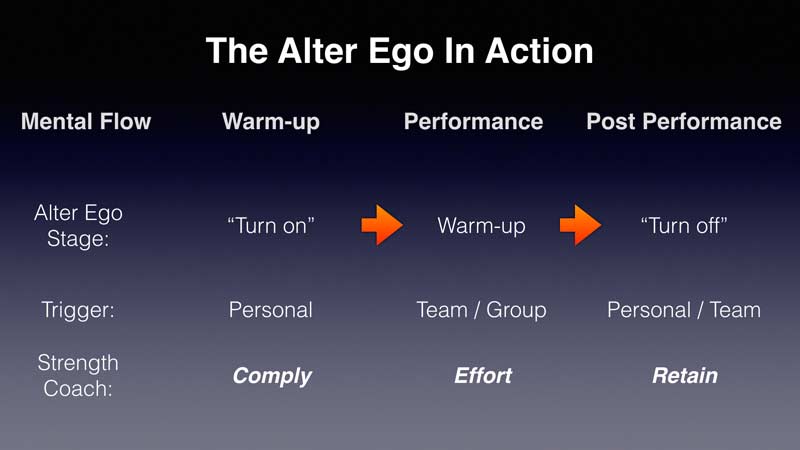

To keep things simple, and to provide the framework, I will talk about two case studies where I actively worked with strength and skills coaches to bring out the alter ego in their athletes. I will cover specific aspects in the comply, effort, and retain model and provide solutions for how to activate each portion in many different ways. The main methodologies for carrying out the alter ego for a strength coach are focusing on the communication and words utilized and tampering with the performance environment.

Case 1: Turn It Up

This past year, I’ve been working with an elite-level hockey skills coach. The two of us were given the task of working together to help an upcoming prospect break through to his fullest potential. The athlete lacked compliance to what was being asked of him, and in turn he lacked both effort and retention of the team’s requests. Outside of performance this athlete is a “nice guy”—he’s extremely intellectual, lets very few people in, doesn’t say too much, and is very methodical in his thinking.

This type of athlete is common. We deal with them on a regular basis: loaded with lots of talent and potential but doesn’t turn it up enough to be their best. As a result, he’d overanalyze a lot of situations, question methodologies, rein in effort, and have extremely slow starts. He left a lot on the table; he wasn’t at his absolute best in the weight room or on the ice. As a result, his job was in jeopardy, and he had to be dealt with immediately.

I carried out my work of finding out what made the athlete tick and worked with him to build an alter ego. It was now up to the skills coach to foster the right kind of communication and environment to pull the most out of the athlete and activate his alter ego. Within three weeks, cooperatively, we helped this athlete not only become a menace on the ice, but also a menace in the weight room. He was more social, intense, and compliant. The coach created an extremely strong environment to bring out the athlete’s alter ego, while I worked independently with the athlete to strengthen this mental skill behind the scenes. As a result, he brought a stronger effort into his on- and off-ice sessions. His compliance, effort, and retention all increased—here’s how.

Once I was able to understand the athlete and what made him tick (aka triggers), I relayed the information to the skills coach. He created an environment to turn these triggers on, or Step 1 to the alter ego, which I call “Turn On.” Before the session started, if time permitted, he focused on having an intense one-on-one conversation with the athlete about why he was here.

He focused on the pain (dark triggers) that the athlete would experience, like a missed opportunity to further his career, if he didn’t take action and be his best. He also focused on the pleasure (light triggers) that the athlete would experience if he did take action and comply fully; he spoke to him about how he’d take a step closer to helping his family financially. He’d also speak about the importance of making sure others were up to par; he’d mention to the athlete the importance of others in his environment being at their best as well, and why it was so important for the athlete to raise the level of others through his own personal work.

There were also days where the skills coach couldn’t catch the player before the training session started, so he’d just use the verbiage with the entire group during their warm-ups. He spoke aloud about connecting their current session to the rest of their careers; while the athletes warmed up, he spoke about them imagining how much pain would occur if they didn’t fully comply and take action during the session. He spoke about the importance of each rep and connected it to the rest of their lives.

The skills coach made it a point to force them to turn off the drama from their personal lives and turn on the intensity of their professional lives by speaking about it. He got them selfish and focused on themselves—he mentally warmed them up to be in a state of pain, or pleasure, lighting up their light or dark triggers and preparing the athletes, whether they consciously had one or not, to turn on their alter ego.

This is the mental warm-up you must put your athletes through, and it’s exactly what it sounds like: warming up the athlete mentally to turn on the alter ego. It works because it puts the athlete in a selfish state of mind; one of the best ways to get someone to comply is by helping them see how the current task helps them personally. Think: You’re dealing with the egos of elite individuals—they didn’t get to where they are by thinking only of others; they focused on themselves.

Mentally warm up an athlete to put them in a selfish state of mind. One of the best ways to get someone to comply is by helping them see how the current task helps them personally. Share on XWhen you’re warming up an athlete mentally to turn on their alter ego and get them to comply, then you have to get the athlete selfish. It’s your job as a strength coach to light up the triggers of the individual and get them focused on seeing the connection of how the current task impacts their personal future. Like my friend from St. Louis, a strength and conditioning coach for elite level football, soccer, and hockey players, always says: “The guys who I’ve worked with who are the most locked in are the ones who are selfish.”

The importance of this is that there’s no “step back and breathe” portion to it. I often hear mental professionals speak about “taking the time to reflect before a performance with the group.” Let’s get real for a second: At the elite level, that should be something athletes do beforehand because they work with a professional like myself to build it into their day-to-day routine. When they get to their performance environment, it’s all business.

As a strength coach in elite environments, you often try to find ways to make the short amounts of time you’re given work. This is all about adapting on the fly to the fast-paced world of elite sports. Being able to pull someone aside for 60 seconds to mentally warm them up and turn on their alter ego is a rare bonus that this skills coach didn’t often come by. That’s why he had to learn the skill of being able to turn on the group versus just turn on the individual.

For the majority of this practice, you will have to be able to light up the triggers of the entire group you’re coaching to create a more competitive environment where every athlete will want to lock in and bring it. When you’re able to home in on the mental warm-up, you take that first step to alter ego: “turn on.” The amazing thing about this was that he not only got positive results out of the individual athlete he was trying to work with, he was able to get more results out of the group as a whole. Eventually, I worked with him to better understand each player that he was dealing with and consulted with him on how to pull the alter ego out of each and every one so that he could get the most out of them, creating a better compliance, effort, and retention rate out of all of them.

During the training session, the coach focused on Step 2: Maintain and Heighten. He actively shouted out directions and instructions to keep the performance environment in what I call “hunting mode.” He tailored his verbiage to become more about the team and less about the individual, and he got them to connect every single repetition to beating the upcoming opponent. This is where everything starts to change; Instead of making it “just another training session” for the team, he made it another day closer to winning against the opponent. Now he not only turned on the alter ego of the majority of his athletes, he was keeping it on.

He praised the positive repetitions of the athletes and spoke about how it was a “winning rep.” He talked about how the team was now “hunting together” instead of just going through the motions. He pulled out collaborative efforts and motivated the team in ways that they hadn’t been motivated before. More importantly, he pulled out the true competitive nature in each athlete without having to waste any time. He kept them locked in and focused, raising the standards of the environment and getting the majority to stay on the same page.

After the training session was done, the coach focused on Step 3: Turn Off. Whether during a cooldown or when he prepared them to go into the weight room after their on-ice session, the coach would speak with the team about how well they “hunted” during the session, and whether it truly resembled the results that the group was after collectively. He also asked the group to reflect on whether they sincerely gave an effort that was worthy of serving their dark and light triggers well. He used that time to speak to how good the group felt now that they’d taken care of business and what they had to do outside of the session. He got them to retain what they just did and focus on what they had to do next.

This is when that individual turned off their alter ego and prepared for what was next. This was a player who previously had been questioned whether he could perform at an elite level consistently, and now they’re speaking about him as the future of an organization. Imagine if this was untouched; imagine if this was left alone. The coach would’ve done a disservice to this high-potential talent, and there would’ve been a career left on the table.

Case 2: Get Relevant

In the second case study, I saw the same results with an elite-level strength coach who had to get more effort and retention out of an athlete who he and I had worked with. The organization had tried to get the most out of the elite-level goaltender for four years. They tried everything from turning it up, to backing off, to outright trying to scare the athlete into working harder and complying. We followed the exact same process with the athlete to help the strength coach pull the alter ego out of the individual.

I figured out the individual’s triggers and created an alter ego for him, and then the strength coach followed the same protocol. He took a bit of a different approach before each training session, however. He made it a point to show up early and speak with the athlete to get him selfish (Turn On and comply). During the training sessions, he made it a point to connect the repetitions and effort rate to the desired team results that the athlete was after (Maintain and Heighten and effort). After the training session, he helped the athlete understand if the effort matched his personal, and the team’s, desired results and helped him focus on what he had to do next (Turn Off and retain).

I was able to consult with the coach on the athlete because I was working with him individually to continue to find the triggers and make sure that he would turn off once the sessions were complete. We started working together on this athlete in September 2018, when the organization viewed him almost as a liability. To date, we have helped this athlete not only break performance barriers in the gym, but also on the ice—making the athlete one of the organization’s most valuable assets to date.

The Danger of Winging It and Doing It Alone

Here’s the thing: Being the “Samurai” in performance is cool, until you don’t know how to turn that Samurai off, and then it starts to disrupt your performance and personal and social lives. How many stories have we heard about athletes who go home and have abusive relationships because they can’t “turn it off”? Or the athletes who become extremely anxious or burnt out because they aren’t able to shut it down?

In both cases that I shared, the coaches had success because I was able to consult with them and teach them about when to shut it down and when to turn it up. Without proper guidance of this coaching tool, you’re playing with fire. I say this because I’m the individual who the athletes call to deal with the issues they face when they can’t turn it off.

It’s important to turn things up, but even more important to shut it down. If you don’t treat this tool (the alter ego) with seriousness and care, then you run the risk of burnout. Share on XIt’s important to turn things up, but it’s even more important to shut it down. What good does it do your athlete if they can only bring it for a day, but are then completely burnt out of the rest of the week? Forget about comply, effort, and retain—if you don’t treat this tool with seriousness and care, then you run the risk of burnout. The reason the first case I mentioned was successful was because the elite-level skills coach was able to receive intel from me on how the athlete was doing outside of performance. The reason that the second case I mentioned with the elite-level strength coach was successful was because he was able to understand how the athlete was feeling before he came into performance.

Both coaches were able to tame the beast that came out in performance, as well as pull it out of the individuals they worked with. In no way did they try to create the alter ego of the individual on their own. This is something that has to be handled with extreme caution and care, as you’re dealing with the identity of an individual both in and out of performance. As much as this can be one of your greatest coaching tools with guidance, it also can be one of your worst enemies without the proper understanding and guidance. Please don’t take chances with this tool.

Ensure Its Effective Use

Everyone has an alter ego. In order to effectively do your job as a strength coach and pull the most out of your athletes, you need to activate this alter ego. It’s your responsibility to motivate the athlete effectively, but most importantly, to do so in a way that doesn’t harm the well-being of the athlete.

The alter ego is an extremely strong coaching tool that’s replicable and viable across many different environments, but to properly utilize this tool you must have the right guidance and care to do so effectively. Again, you are doing your athletes a disservice if you know this coaching tool is here, but don’t take advantage of it. Don’t just wing it—empty the tank.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Allen, M.S., Jones, M., McCarthy, P.J., Sheehan-Mansfield, S., and Sheffield, D. “Emotions correlate with perceived mental effort and concentration disruption in adult sport performers.” European Journal of Sport Science. 2013;13(6):697-706.

Bray, C.D. and Whaley, D.E. “Team Cohesion, Effort, and Objective Individual Performance of High School Basketball Players.” The Sport Psychologist. 2001;15(3): 260-275.

Cusella, L. P. Feedback, motivation, and performance, Handbook of organizational communication: An interdisciplinary perspective. (p. 624-678). 1987: Sage Publications, Inc.

Fehr, E. and Fischbacher, U. “Why Social Preferences Matter – the Impact of non‐Selfish Motives on Competition, Cooperation and Incentives.” The Economic Journal. 2002;112(478):C1-C33.

Gillet, N., Valleranda, R.J., Amoura, S., and Baldes, B. “Influence of coaches’ autonomy support on athletes’ motivation and sport performance: A test of the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2010; 11(2):155-161.

Harwood, C., Hardy, L., and Swain A. “Achievement Goals in Sport: A Critique of Conceptual and Measurement Issues.” Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2003;22(3):235-255.

Terry, D.J., Hogg, M.A., and White, K.M. “The theory of planned behaviour: Self‐identity, social identity and group norms.” British Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;38(3):511.

van der Werff, E., Steg, L., and Keizer, K. “The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour.”Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2013;34:55-63.

Van Knippenberg, D. “Work Motivation and Performance: A Social Identity Perspective.” Applied Psychology. 2001;49(3):401.

Yves, C., Guay, F., Tzvetanka, D.-M., and Vallerand, R.J. “Motivation and elite performance: an exploratory investigation with Bulgarian athletes.” International Journal of Sport Psychology. 1996;27(2):173-182.