No one has enough athletes. Across youth sports, participation rates have been on the decline for years, and when kids do pick up a sport, there’s a significant chance they will only play for a few years and then quit before they’re out of elementary school. And this was before COVID-19 disrupted the youth sports landscape—we still can’t put a number on how many kids just never came back after sports and teams and leagues shut down in 2020.

Which is why discussions of multisport participation tend to become so contentious—while generally framed as a methodological debate, the root is, in fact, a scarcity issue. If a kid likes to paint AND likes to write poetry, no one insists they need to choose one or the other or tries to make a case for why performing some combination of the two will lead to a coveted scholarship. Why? No adult or organization is incentivized to do so. Pursuing one activity does not preclude the other, and though artistic talent is appreciated and recognized as a rarity, as an asset, it is not invested with scarcity.

Discussions of multisport participation tend to become contentious because while generally framed as a methodological debate, the root is, in fact, a scarcity issue, says @CoachsVision. Share on XEarly specialization versus multisport, on the other hand, is a competition for a pair of dwindling resources: athletes and their time.

But, but, but…we don’t like to talk about an explosive, coordinated, and competitive 10-year-old in the cold-blooded terms of an asset, so those coaches vying for this kid’s limited time will gild their pitch in an altruistic framework—rather than concede they just don’t like sharing, they will insist they’re genuinely looking out for that athlete’s future.

Is there one “right” way to develop that 10-year-old? No—kids are all different, and they respond to different things. All roads lead to Rome is one of the few sports clichés that doesn’t spark contrarian disagreement because most coaches have anecdotal proof that this is so.

My favorite team on the planet is the USWNT—and there is no single or preferred route that the women on the team followed to reach this pinnacle of U.S. soccer. You have the 24/7 soccer junkies like Tobin Heath and Mallory Pugh, who wanted to eat, sleep, and breathe soccer from a very young age. These kids exist. What are you going to be for Halloween? A soccer player. What do you want to be when you grow up? A soccer player. What are you doing this weekend? Playing soccer. Is something bothering you? No, today’s just boring because I don’t have soccer.

Meanwhile, you also have multisport varsity athletes like Becky Sauerbrunn (soccer, volleyball, and basketball) and Sophia Smith (soccer and basketball). Telling a young Mallory Pugh she should swim or play field hockey as a way to get better at soccer would have been as ridiculous as telling a young Becky Sauerbrunn she needed to drop all her other sports if she wanted to fulfill her potential on the pitch.

Though there isn’t a right way to develop that 10-year-old, there is definitely a wrong way—while all roads can lead to Rome, the scarcity of athletes and the number of kids who’ve quit sports by the age of 13 indicate that most don’t get to where they’re going. (And let’s be clear, *Rome* is not the national team or the pros or D1; it’s any goal-based destination: a high school team, a higher-level club team, or just improved performance on a current youth team.)

What’s the wrong way? See that burned-out 14-year-old who’s announced they’ve “retired” from sports and now spends their afternoons on TikTok and SnapChat? Whatever path they took, that was the wrong way.

While navigating this road of dead-ends, detours, and wrong turns, here are the five biggest misconceptions I see when it comes to #Multisport.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11163]

1. Multisport Participation Is What Made an Elite Athlete “Elite”

Choose your big game—the College Football Playoff National Championship, the NBA Finals, the MLB World Series—and sure enough, an announcer will note that one of the impact players was also a two- or three-sport high school athlete. Like clockwork, on social media, some coaches will preempt the debate by posting “Oh great, cue all the multisport fanboys who are going to claim it was playing three sports that made them a superstar.”

Let me speak for multisport advocates when I say, no, we don’t believe that at all.

If you’re 6’5”, 225, and run a 4.5 in high school, you can write your own ticket. Want to play tight end and outside linebacker on the football team? Game on, here’s a helmet. Power forward on the basketball team? Done, please just try to work on those free throws now and then. 1B on the baseball team? Position’s yours to lose. Walk up to the volleyball or rugby or water polo coach and say I’ve never played before, but I’d like to try? No problem, we’ll teach you.

We get it. Transfer from his days as a blue-chip football star did not make Frank Thomas a HOF baseball player—being 6’5”, 250, and athletically gifted made The Big Hurt someone who could play whatever he dang well pleased.

Can multisport participation benefit those same elite athletes? Of course.

Watching Antonio Gates “box out” a strong safety to make a catch right at the first down marker, you could see the clear crossover of his basketball skill set. Watching Abby Wambach get up off the ground on one leg to score with her head, you could envision her attacking the glass for thousands of layups. But again, while Antonio Gates and Abby Wambach demonstrated their diverse athletic backgrounds in the unique ways they played an elite sport, they played at that elite level because they had body types and athletic abilities that are present in only the smallest fraction of 1% of the human population. That’s it.

Multisport advocates understand this. It is only brought up as a bad-faith strawman to argue against by those who are incentivized to alternately suggest…

2. Multisport Participation Is Only Viable for Naturally Gifted Athletes

That kid who’s going to be 6’5”, 225, and run a 4.5? Yeah, he just transferred to your kid’s school and took your son’s starting spot. What are you going to do now?

Better roll up your sleeves and get after it. Hard work beats talent when talent doesn’t work hard.

This is the pivotal moment many sport coaches seize on to pitch early specialization. They grant that multisport participation is a luxury that physically dominant athletes can indulge (and that they will grudgingly allow for those impact players). But since you and your kinda short and never-fast spouse failed your offspring in the DNA sweepstakes, now you’ve got to pay up and teach your kid to love the grind.

The issue isn’t whether or not specialization works—it does! The question is how long will it keep working, says @CoachsVision. Share on XSpecialization sells because it’s an easy sell—the promised outcome is something we want to believe. The existence of a direct path from deliberate hard work to a desired destination is the core of the American Dream. (But it’s based on a falsehood, because while talent + hard work does beat lazy talent, lazy talent still beats hard-working non-talent. I’m sorry, it’s true.)

The issue isn’t whether or not specialization works—it does! The question is how long will it keep working?

In the short term, specialization produces immediate and startling results. While not exactly scientifically verified, the equation is simple:

- Specificity x Intensity = Magic

No joke. Take kids who practice and play baseball or basketball or soccer a couple times a week for a three-month season in a moderately competitive league. Then, have them instead practice and play five days a week in a highly competitive, 6- to 9-month season.

MAGIC—their technical and tactical abilities will skyrocket. Their parents will be thrilled. Total immersion works. That is, until it doesn’t.

Video 1. This walk-off, 8-6-5-4 double play during 12U Western B-Nationals was made by girls in the fifth, sixth, and seventh grades and is the type of moment that electrifies parents, justifies travel costs, and lights up social media accounts—even the umpire is fired-up. And these moments only occur among athletes who can develop high levels of technical and tactical skill in a setting that pairs specificity and intensity.

If I want my 10-year-old to learn Spanish, I can put her in an Intro to Spanish class or a Spanish Immersion Program. I know for sure which one will have her speaking much better Spanish after six months—the problem, though, is I don’t know which one will put her on track to speak better Spanish when she graduates from high school. Immersion compels two responses: assimilation or rejection. So, while the downside of the introductory course is that she will pick things up at a much slower pace, the downside of the immersion program is that she may reject the overwhelming demands of that system and decide she never wants to learn another language again.

The problem with the *magic* equation is that it’s based on a pair of ephemeral and non-renewable variables. Once you’ve burned all the way through specificity and intensity…POOF, they’re gone. When that happens, you better have some other serious tricks up your sleeve: All roads lead to Rome, except those that lead to a dead end.

3. Playing a Second or Third Sport Will Make You Better at Your Best Sport

For athletes under 12, the number one reason to play multiple sports isn’t some alchemic synergy whereby the combined effect will make them far better at their best sport. The best reason for young kids to play multiple sports is that there’s simply no way to look at an eight- or nine-year-old and identify what their best sport is in the first place.

The best reason for young kids to play multiple sports is that there’s simply no way to look at an 8- or 9-year-old and identify what their best sport is in the first place, says @CoachsVision. Share on XProviding kids with the opportunity to have fun and play multiple sports gives them the ability to gravitate toward the sports they like the best while not foreclosing other options by going all-in on any one. If a normal kid washes out of soccer at 14, and they’ve never swung a bat, dribbled a basketball, or learned to swim, those specific skills will be very hard to pick up at that point.

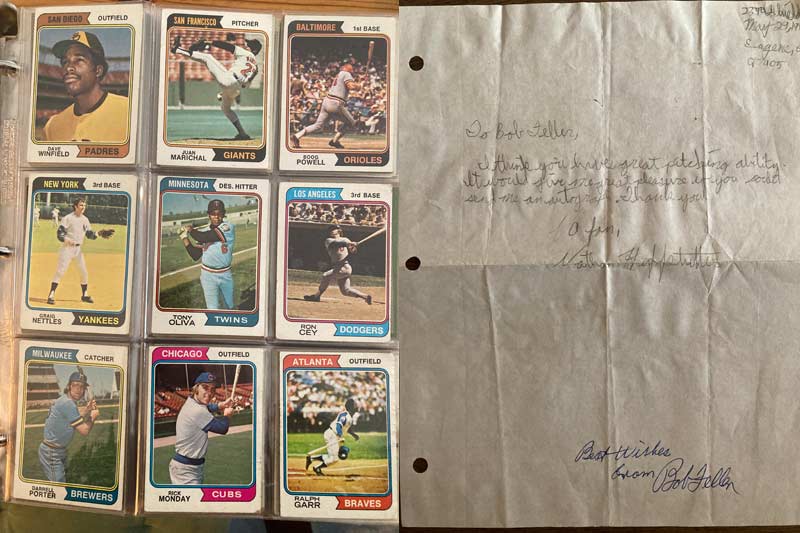

In middle school, I was on the baseball, flag football, soccer, basketball, and wrestling teams. If I had to choose ONE sport at that age, it would have been baseball. Second choice? Football. Why those two? Because I followed them obsessively as a fan—I collected the cards, memorized the stats, read the paperback biographies, and my heroes played in the MLB and NFL.

Young kids play the sports they play for numerous reasons—their parents sign them up for the sports that they played when they were younger, the kids have friends on the team, they like to watch it on TV, they think the uniforms and gear are cool, and so on. Actual compatibility with the sport isn’t nearly as big of a factor until after puberty. Ultimately, I went on and played soccer and basketball through high school. Why those two? I couldn’t hit a curveball or keep weight on my frame, but I did have the body type and all the physical tools to play center-mid on the soccer pitch and run the three on the basketball court.

Even for non-dominant athletes, are there useful physical qualities that can be developed by playing multiple sports? Heck yeah.

I don’t care what sport you coach, if you watch a 10-year-old running routes on offense and then covering those routes on defense in a 7v7 flag football game, you are watching an “all-sports relevant” speed and agility program being executed with pace and intent. How much easier is it to teach a drop step to a baseball player who already knows that footwork and body position from football? How much better at tracking punts and long balls is a soccer midfielder who has also caught thousands of flyballs as a softball center fielder?

And, on the flip side, watch your never-played-any-sport-but-softball player try to get out of a rundown between home and third. Watch your early-specialized soccer player try to get off the ground to score on a header off a corner kick.

It’s not pretty.

Those kids are often missing something in their movement literacy, and sport-specific skills are impossible to teach in the absence of the necessary physical ability to perform those skills. Kids have a pre-maturity window to maximize fluency in as many foundational movement patterns as possible, and multisport participation is an effective way to fill these buckets.

Sport-specific skills are impossible to teach in the absence of the necessary physical ability to perform those skills, says @CoachsVision. Share on XBut just because there can be developmental advantages, that doesn’t mean there will be. While the Specificity x Intensity equation is neat and tidy, there is no comparable calculus for how multisport participation will cross over. At that aforementioned 7v7 flag football game, you can also watch players on the field who don’t appear to be getting better at anything. And for that soccer midfielder to get any type of transfer from those 1,000 fly balls, they must want to be there and put dedicated effort into actually catching them.

Kids must love their second or third or fourth sports for there to be any upside relative to a first. And if a kid struggles with key technical skills in a sport—such as throwing strikes or hitting in baseball, shooting in basketball, first touch and passing in soccer—playing other sports will not only not help them improve at those technical deficiencies, but the time demands involved in those extra sports may well prevent them from putting in the specific practice to improve at those deficiencies.

4. The Primary Benefits of Multisport Participation Are Physical

Although a flag football game checks any number of developmental boxes, kids don’t have to play flag football to check those identical boxes. Here on SimpliFaster, performance coaches like Elisabeth Oehler, Jeremy Frisch, Brandon Holder, and Nick Gies have shared strategies for creating LTAD-based movement programs, and Mike Whiteman has elaborated on how he designs strength and conditioning programs to fill the missing buckets for specialized soccer players.

No stressful tryouts, no travel demands, no costly uniforms or gear, no year-round commitment—instead, game-based movement, fun, and physical development. These can all be successfully accomplished outside the confines of an organized sport.

A few benefits of multisport participation that are much harder to replace, however, are the mental ones:

- Stress reduction

- Problem-solving

- In-game resilience

Stress Reduction

Sports are filled with pressurized moments—whether taking a breakaway shot or a PK in soccer (or being the goalkeeper in those situations), pitching and hitting in softball/baseball, shooting free throws or clutch shots down the stretch in basketball, making a catch during a last-minute drive in football, and so on.

For competitive kids, the ability to switch gears and take on a different role in a different sport with different individual demands has real psychological benefits, says @CoachsVision. Share on X“Gamers” love those moments, but they are meant to be just that, momentary. Add repetition, accumulation, and high expectations, and those stressful situations become fatiguing. For competitive kids, having the ability to switch gears and take on a different role in a different sport with different individual demands has real psychological benefits and can promote longevity in all the sports they play.

Problem-Solving

Learning to play chess is not just learning how to move those pieces on that board; it’s learning to play any game that involves choosing an attacking strategy while simultaneously anticipating and reacting to an opponent’s moves. Likewise, learning to play an attacking sport helps athletes discover creative ways to play other attacking sports and solve the problems that are presented in dynamic situations.

Those expressions of creativity can be as simple as a basketball player having a greater understanding of how to use their eyes and head to sell a fake on the soccer pitch. They can also be the more complex way that a softball catcher who recognizes when to sacrifice a run to get a sure out will also know when to challenge for a loose ball instead of containing and protecting their own goal or basket.

Resilience

On the opposite side of stress reduction, players who play multiple sports often do appear more comfortable in those acute, pressurized moments because they’ve been in comparable situations elsewhere. A PK in soccer or last-second free throw in basketball is a different thing with players who have also had to throw a strike on a 3-2 count with the bases loaded or needed to get a clutch hit in a tie game with two outs and a runner on third.

5. Multisport Athletes Lack Commitment

So, what, they just don’t want to commit?

I regularly hear this misconception from mystified ECNL soccer coaches and “elite” travel softball managers about my players who play both sports on the multisport-based teams I coach. If you are the parent of a multisport athlete, you likely have heard the same question. This is based on a false dichotomy that choosing to play a sport should mean that you are also choosing not to play others.

In reality, the “commitment” debate is born of that same scarcity issue mentioned at the outset—the year-round model for club sports depends on coaches who coach year-round and, consequently, players who are perpetually available to play.

The belief that multisport athletes lack commitment is based on a false dichotomy that choosing to play a sport SHOULD mean you are also choosing NOT TO PLAY others, says @CoachsVision. Share on XThough some club coaches are indeed fully bought-in and devoted to early specialization as THE route to sports success, in my experience, those true believers are in the minority. Instead, the majority of youth sport coaches will say “Absolutely, I love multisport athletes” while leaving unsaid the remaining half of that sentence “…as long as they never miss any of my practices or games.” While professing this passion for multisport athletes, those same coaches will set out a year-round playing schedule that is, in fact, utterly incompatible with multisport participation.

We won’t have any team activities from 5:00 a.m. to 6:30 a.m. on Friday mornings in November and December, so if she can play another sport during that time, have at it!

Hyperbole aside, the limited time to play another sport is far and away the largest obstacle to competing in several competitive sports. Because, more often than not, your best youth players are also the ones who don’t miss anything—the same intense focus that motivates them to drive the action on the field also motivates them to not miss any of that action.

Being a multisport athlete in the modern youth sports landscape is a remarkable act of commitment. It requires feats of scheduling, transportation, and communication, as well as a budgeting of time, money, and physical energy. The demands of the game require the dedication to master the specific technical skills of each sport, whether that be through extra private coaching or self-directed effort.

It’s hard, and it cannot be done without a true sense of “commitment.”

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11139]

Addressing the Scarcity Issue

One of the paradoxes of youth sports is that we are successfully developing a top tier of players who become very good at their sports at a very young age…but that accelerated rate of development among the few ultimately makes wider-scale team formation very challenging. How do you surround those highly accomplished players with comparable talent? If you put all the best players on the same team, whom do they play?

As the model then shifts from coaches developing the players who they have in their local backyard to recruiting “elite” teams of the best players they can aggregate, the developmental pyramid gets upended, with decisions being driven by what is best for the smallest percentage of participants. That top level already has a Darwinian attrition rate baked in, and then when the middle and base levels of the pyramid opt out because the game has not been designed to be fulfilling for them…things fall apart.

And here we are, where nobody has enough athletes.

So, what is the answer to the scarcity issue? Retention.

Will the majority of your athletes come back to play the sport next year? Specialized or multisport, if the answer is no, then you’re contributing to the scarcity issue, says @CoachsVision. Share on XThere is one measure of success for a youth coach—will the majority of your athletes come back to play the sport next year? Specialized or multisport, if the answer is no, then you’re contributing to the scarcity issue. The reason we create these pathways through sports is to get to Rome. Whatever it takes, keep your players on the road.

Lead photo by Speed Media/Icon Sportswire.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF