In Illinois, an alarming number of football coaches discourage participation in track. A sample conversation:

Sophomore football player sends a DM to his head football coach:

-

Would it be a bad idea to run track this season? I was looking forward to running this year, but I talked to Coach ***** and all he said was “out of sight, out of mind.”

The Head Coach responds:

-

Your call. I tell guys: “if it’s a passion you can’t live without, then you should go out.” I don’t subscribe to the adage that track makes you faster, if that’s why you go out. It’s a totally different type of speed than what is needed in football. The biggest reason why juniors don’t play in our program is a lack of strength, not speed!

And so it goes—another football coach convinces a sophomore in high school to lift weights in the spring with that coded warning, out of sight, out of mind. The guy who said that should be fired and never allowed to coach again.

Why? Since 2017, 1292 high schools in Illinois produced only 936 Division I football players. Only 44% of those athletes ran track. By comparison, since 2017, Texas produced 3209 Division I football players. 71.5% ran track. Texas had more football commits run track (2371) than Illinois had D-I players (936). And it’s not getting any better in Illinois—in the class of 2021 (131 D-1 football commits), only 39% ran track.

When you look at the combined rosters of Alabama and Ohio State, 88% of the DBs, 83% of the WRs, and 75% of the RBs ran track. 61% of all the players on both rosters had a track background.

When you look at the combined rosters of Alabama and Ohio State, 88% of the DBs, 83% of the WRs, and 75% of the RBs ran track. 61% of all the players on both rosters had a track background. Share on XFeed the Cats Meets the BCS

Like modern politics, football coaches live in echo chambers. Every football coach I know was a hard-working grinder as an athlete. The weight room was their sacred place. Most of them never won a race in their life, and when they think of running, they think of conditioning.

Every football coach loves fast players, but they see speed as a genetic trait. They love it…then neglect it. They hire big guys to serve as their strength and conditioning coaches. The University of Illinois just replaced their S&C coach. Their guy was a power lifter who would post pictures of his biceps while he bragged about the number of Illini football players who could bench 405 and clean 300 pounds. He also posted video clips of his athletes going through speed ladders with the hashtag #SlowFeetDontEat. The new Illini S&C guy goes by the name of “Tank.” Tank got married in a college weight room.

And so it goes.

Chris Korfist and I started the Track Football Consortium in 2015. Our mission was to bring track coaches and football coaches together for the benefit of athletes. The goal was to help football coaches to understand and prioritize speed and power. Too many football coaches see the game through the lens of hard work and high effort, not the lens of maximum velocity and high outputs. Track coaches need help too. The average track coach comes from a distance background or subscribes to a run-them-to-death, 10×200 program. Originally, the college S&C world was not even on our radar.

Now it is.

This article has been in my head throughout the fall season. While writing this, on the day after the NCAA National Championship Game, I tweeted: “It really seems like last night was a tipping point.” And it truly feels like something happened, where things will never be the same again. It’s like Julius Caesar crossing the Rubicon. Huh? Tipping point? Crossing the Rubicon?

People in our Feed the Cats and TFC-world have been acutely aware of those rebel talents of the strength and conditioning field who are making a break from the meathead approach to football. We watched with excitement as, in their prior positions at Indiana, David Ballou and Dr. Matt Rhea helped make the Hoosiers relevant as a football program.

Matt Rhea was quoted in a Stack article, How a Unique Speed Training Program Flipped the Fortunes of Indiana Football, saying what makes him revolutionary: “The old adage you can’t teach speed or you can’t develop speed in guys at this level is just highly inaccurate.” Also from the same Stack article: Rhea, along with IU Director of Football Performance Dave Ballou, arrived in Bloomington in January of 2018. Over the course of the next year, Indiana players saw their top running speed increase by an average of over 3 miles per hour.

For those of you new to the miles per hour game, DK Metcalf ran 1.37 mph faster than Budda Baker in the famous rundown back in October 2020.

College teams recruit fast athletes. I can’t imagine what an average speed increase of over 3 miles per hour would look like.

When Rhea and Ballou went to Alabama, I told people that Alabama may never lose another game. Especially given the Neanderthal state of affairs in many S&C programs.

When @MattRheaPhD and @UA_CoachBallou went to Alabama, I told people that Alabama may never lose another game, says @pntrack. Share on XYou see, Alabama has always recruited the best athletes in the country. Unlike the NFL, where the worst teams are awarded the top draft picks, the best college programs get multiple first round picks every year. There’s nothing fair about recruiting. The rich get richer. Filthy rich. Bad teams are screwed. Alabama has always been rich in talent.

But what happens when you train those future NFL players the right way? What happens when you stop doing s**t that makes players slow? What happens when speed becomes the priority and the weight room becomes a part of the plan, not the plan?

“When you stop viewing the weight room as a place to break athletes down and start viewing it as a place to build them, your perspective on stress shifts from excess to optimal.” ~ Matt Rhea

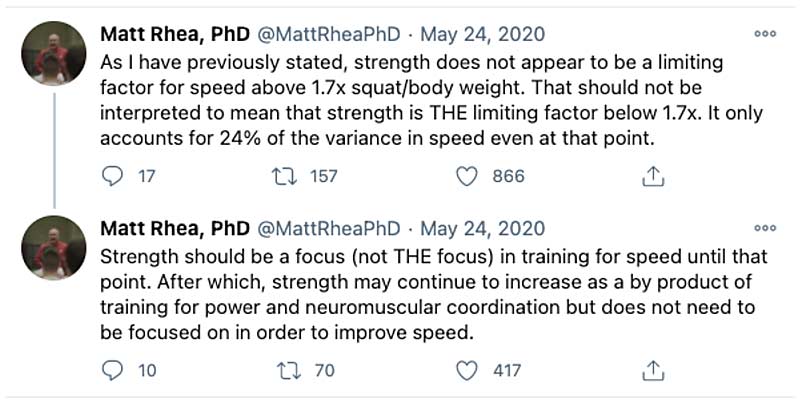

The prioritization of speed can be seen in this tweet by Dr.Matt Rhea from last May:

The greatest sprint coach in the country, Boo Schexnayder, recognized the significance of Matt Rhea.

Alabama Recruits Multi-Sport Athletes

Matt Rhea’s work is brilliant and will forever change football in America. However, don’t underestimate the talent he gets to work with.

Tyler Leising at Tracking Football provided me with some of Tracking Football’s data showing the multi-sport connection to Alabama recruiting:

- 73% of Alabama’s roster were multi-sport athletes in high school and 64% ran high school track.

- This year’s Heisman Trophy winner, DeVonta Smith, was a track athlete and played high school basketball. 10.67 in the 100m. Also solid in the 400: 49.34. Smith is projected as a top ten pick in the NFL Draft.

- The other projected top ten pick in the draft is Patrick Surtain II, who ran 10.87 in the 100m at American Heritage H.S. in Fort Lauderdale.

- Jaylen Waddle missed most of the season with an ankle injury, but still projects as a first round pick. Waddle ran 10.84 in the 100m, and like many wide receivers, excelled as a long jumper (22’9”). Waddle also played basketball.

- Quarterback Mac Jones will also likely get picked in the first round. Jones was not a multi-sport athlete in high school.

- The fifth potential first-round pick coming out of Alabama this year will be 6’4” 310 pound DE Christian Barmore. Barmore was not a multi-sport athlete in high school.

- At 226 pounds, Najee Harris played basketball and ran track in high school. 11.19 in the 100m.

- Wide receiver John Metchie III played lacrosse at a high school in New Jersey.

- Wide receiver Slade Bolden played baseball in high school.

- 6’6” 320 pound offensive tackle Alex Leatherwood threw the shot put 49’3” in high school.

- Center Chris Owens threw the shot 46’10” in high school.

- 6’3” 327 pound Emil Ekiyor Jr. played basketball in high school.

- 6’5” 242 pound tight end Miller Forristall ran a 52.53 400m in high school.

- 6’4” 222 pound linebacker Christian Harris ran 11.53 in the 100m.

- Starting CB Josh Jobe ran 10.90 in the 100m, 21.56 in the 200m, and ran on a super-fast 4×1: 40.97.

- Safety Daniel Wright ran the 400m in 48.60, high jumped 6’4”, and long jumped 22’6”.

- Safety Jordan Battle played basketball and ran the 200 in 22.21.

Alabama’s Pipeline to the NFL

Since 2010, Alabama has sent 143 players to the NFL. That’s an average of 14.3 per year, meaning that on any given Alabama roster, there’s probably 57 future NFL players.

60% ran high school track. (The #1 best sport for building athleticism!)

50% played high school basketball. (The second-best sport for building athleticism!)

19 ran under 10.99 in the 100m.

18 long jumped over 20 feet.

10 threw the shot over 50 feet.

The Future of Speed-Based Football

Alabama will continue to recruit the best athletes in the country. Those participating in track and field will have verified athleticism and will have special value.

But, everyone recruits the best athletes. Everyone recruits track athletes. Ohio State’s roster featured an incredible 78% multi-sport athletes. 57% of their roster ran track in high school.

LSU’s Ed Orgeron went on the recruiting trail looking for track athletes as soon as they won last year’s national title. He had lots of work to do after FOURTEEN of LSU’s players were drafted by the NFL.

With everyone beating the bushes to find the fastest high school football players, the difference will become the training of those athletes at the college level. Will multi-million dollar football programs continue to turn their athletes over to bodybuilders, powerlifters, and cheerleaders?

With everyone beating the bushes to find the fastest high school football players, the difference will become *the training of those athletes at the college level,* says @pntrack. Share on XWill NCAA college football teams continue to recruit speed…then neglect it?

Will the S&C world continue to celebrate the number of players benching 405, cleaning 300, and then publish embarrassing videos of the world’s best athletes going through speed ladders?

Or will we find people who can make those athletes faster and more powerful?

The Rubicon has been crossed.

The rest of college football will adapt or get left in the dust.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF