As strength and conditioning coaches, our job is to help create the adaptations we want in our athletes. Our choices of which exercises to use, how much volume to prescribe, and how to properly intensify training sessions all play a part in whether our athletes will achieve the desired adaption. This can be a difficult task since:

- Many of the adaptations we train for require specific training parameters.

- Most athletic teams have a wide variety of fitness levels and training ages.

Whether improving muscle mass, strength, power, speed, aerobic conditioning, glycolytic conditioning, or the ATP-CP system, we need to know how to do this for athletes of all skill levels.

This article lays out research, experience, and practical applications for improving hypertrophy in beginner, intermediate, and advanced athletes. With all of the qualities listed above, there needs to be a stress and a period of recovery to elicit specific adaptations. We cover how to optimally create the stress needed to accomplish the goal of muscle hypertrophy:

- What hypertrophy is.

- How hypertrophy is measured.

- How to improve hypertrophy in different levels of athletes (a beginner to building muscle, an intermediate, and an advanced athlete who already has a lot of muscle mass and just needs to find a way to add on a little more).

Mainly, in this article, we provide methods that coaches can implement with athletes at all different training ages.

What Is Hypertrophy?

Hypertrophy, as defined by Oxford, is the enlargement of tissue from the increase of the size of its cells. This is not to be confused with the ever-elusive hyperplasia, which is the enlargement of tissue from an increase in the number of cells. Muscle hyperplasia is a controversial topic in strength and conditioning (just like aerobic conditioning and back squats, for whatever reason), so we won’t touch on that topic today.

A free way to measure muscle growth is through girth/circumference measurements: wrap a tape measure around your flexed bicep, perform bicep curls for 8 weeks, remeasure & see if your arm is bigger. Share on XThe gold standard for measuring muscle hypertrophy is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but we are strength coaches and don’t work in a lab. Ultrasound machines have also proved to be effective, and DXA scans are excellent at measuring overall body composition changes—but, again, those need special, expensive equipment. A free way to measure muscle growth is through girth/circumference measurements: wrap a tape measure around your flexed bicep, perform bicep curls for eight weeks, remeasure, and see if your arm is bigger.

How Does Muscle Hypertrophy Occur?

There are two parts to any desired adaptation: stress and recovery. Let’s assume our athletes are recovering optimally—you know, getting adequate sleep, maintaining perfect macro and micronutrient ratios, and having lower stress levels. (We know it’s very unlikely, but let’s just assume.) So there needs to be a stressor, a signal to the system to tell the body to make the muscle bigger. The main process for this is through muscle protein synthesis, which is the body using proteins to build new muscle tissue. There seem to be three main ways to signal the body to increase muscle size:

- Mechanical tension

- Metabolic stress

- Muscular damage

Muscular damage has fallen off a bit as a driver of hypertrophy. Studies out there have found that muscle damage does lead to more protein synthesis, but most of that protein synthesis is used to repair the damaged muscles, not grow bigger fibers.

So that leaves two options—mechanical tension and metabolic stress. Mechanical tension is lifting progressively heavier weights through a full range of motion. Metabolic stress is the “pump” feeling people get from lifting weights, which is the tissue being full of metabolites (lactate, hydrogen ions, etc.). Both lead to muscle protein synthesis, and both methods stress the tissue in a way that signals to the body that this muscle needs to get bigger to keep up with this type of work.

Science is still changing on muscle hypertrophy as we continue to learn what actually leads to muscle growth and what does not: “Conclusively identifying major hypertrophy stimuli and their sensors is clearly one of the big remaining questions in exercise physiology.”5 How do we do this with different levels of athletes?

Hypertrophy Adaptations for a Beginner Athlete

Oh, the glorious days of the newbie gains, where you can walk into your local gym, do anything, and get bigger. We worked with a 14-year-old baseball player who had put on over 10 pounds of body weight in the off-season, just focusing on the basics. We focused on proper form, being consistent as far as showing up and working out, and progressive overload.

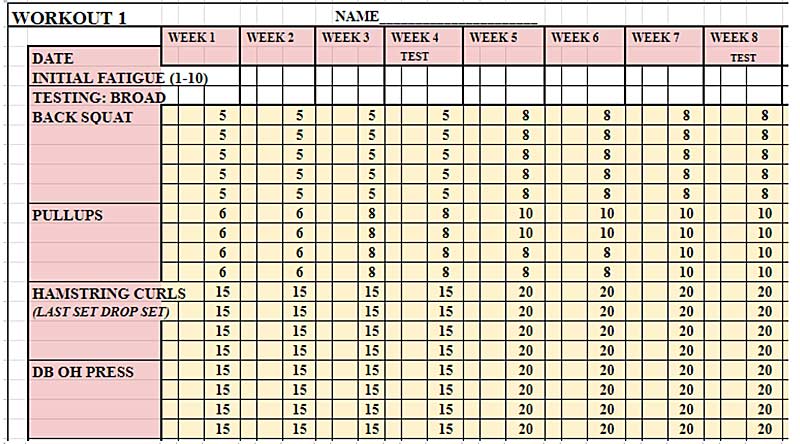

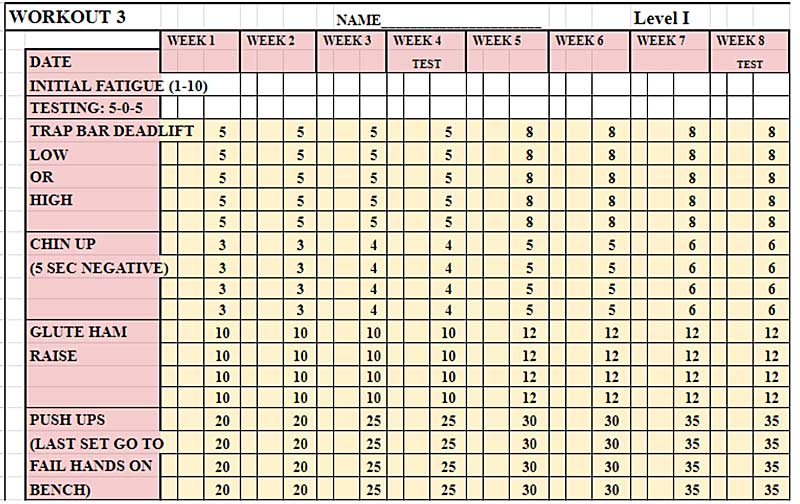

- Proper form. This is not new information to you coaches, but if an athlete does not lift with proper form, they won’t be an athlete very long. And, for hypertrophy purposes, they won’t be stressing the desired tissues you want to grow. We have all seen the back squat form that is growing bigger low back muscles than leg muscles. Hopefully, this is not a topic we must spend much time on.

- Being consistent. We all know athletes do not work out one time and magically look like Ronnie Coleman. This is a long process, and studies show over and over again that a bad workout program done consistently will lead to more improvements than a perfect program that athletes do once per month. Yes, that means the workout they do in the garage with their uncle done consistently over time will be more beneficial than the workout program that you, Louie Simmons, and Charles Poliquin design for them that they do seven times over the summer. Make them enjoy the weight room and want to come in and lift. That’s a whole other article.

- Progressive overload. This is really step one to building muscle, the story of Milo. Do an exercise for a certain number of sets and reps. The following week, do that same exercise for one more rep per set or with a little more weight. Do that for years, and you’ll have a freak on your hands.

-

There is no need for special rep schemes yet; we should know by now that 8–12 reps are great, but really anything done for 5–30 reps within a set should lead to the same amount of muscle growth as long as athletes push the set reasonably close to failure. The beginner does not even need to be that close to failure; leaving 3–4 reps in the tank will still lead to growth, all while being safe and doing the movement correctly.

Although your athletes need to be consistent, a newbie does not need to be in the gym every day. People progress by lifting one day per week, believe it or not. Two lifts per week is also great.

Although your athletes need to be consistent, a newbie doesn’t need to be in the gym every day. People progress by lifting one day per week, believe it or not, says @steve20haggerty. Share on XYour new lifter is like a new tube of toothpaste—you can press anywhere on the tube, and toothpaste comes out. Push on the front, back, side—you can even push away from the hole, and toothpaste will come out. It’s when you get more and more advanced athletes that you need to start pressing harder, pushing in a certain direction, or even twisting, folding, and rolling up the tube to get a smidge of toothpaste. (I stole this analogy from Keir Wenham-Flatt.)

Hypertrophy Adaptations for an Intermediate Athlete

No more three sets of 10. Your athlete has been training consistently now for a year or so and maybe has even made a comment about not getting any bigger. They no longer just look at Muscle and Fitness Magazine and instantly grow.

With intermediates, it’s still essential to lift correctly, be consistent, and progressively overload—these things will never go away. But now it’s time to add in a little bit more specific work: focusing mainly on compound movements, progressing volume, pushing each set a little closer to failure, playing around with different rep ranges and lifting tempos, and starting to add in more lifting days.

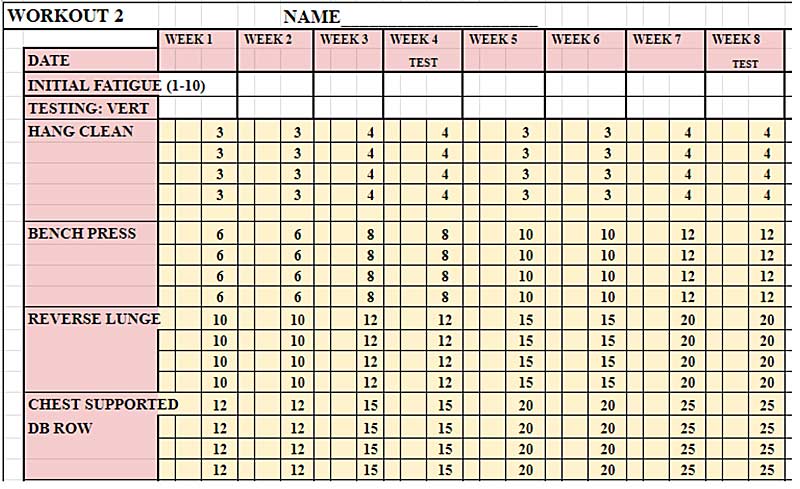

- Compound lifts. The magic of compound lifts such as squats (front, back, goblet, safety squat bar…I’m not married to any of these; they all work), deadlifts, bench presses, pull-ups, etc. is that they stimulate the whole body. Yes, the squat will work the legs better than the bench press will, but both lifts utilize many different muscle groups and stimulate growth across the entire body. As noted earlier, mechanical tension (load) is a huge driving force of muscle growth. No exercises allow for more load across many muscle groups than compound lifts do.

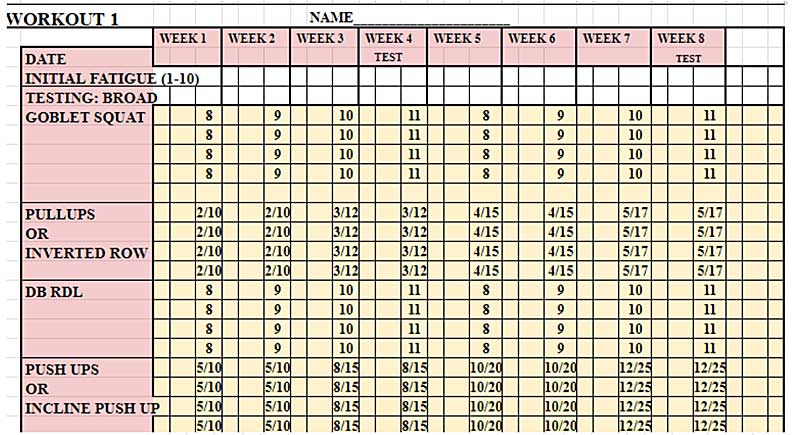

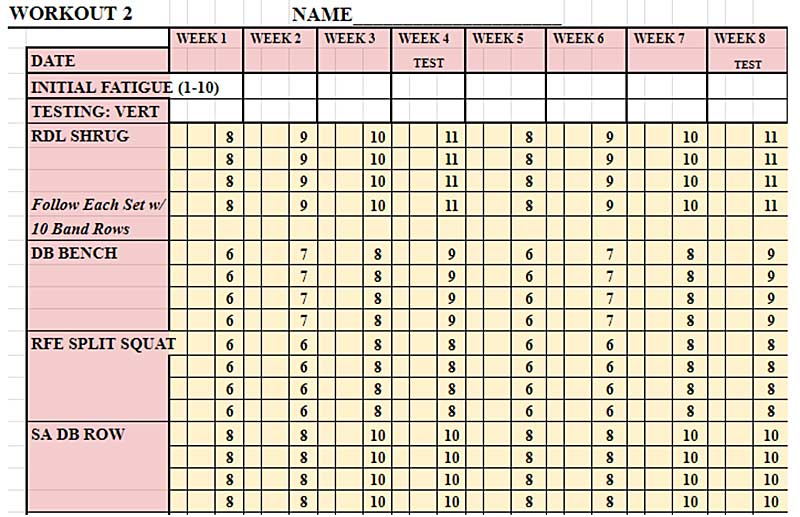

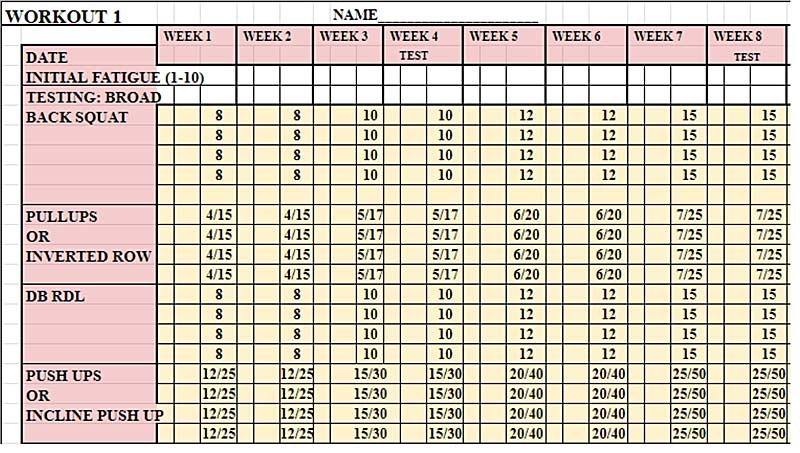

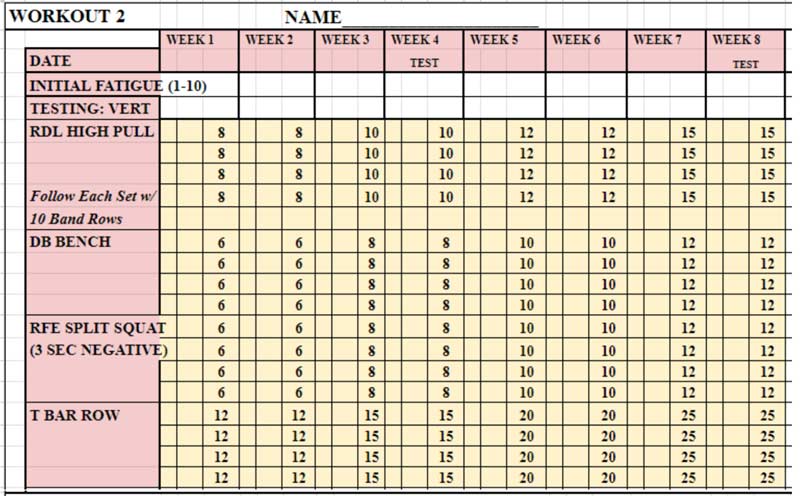

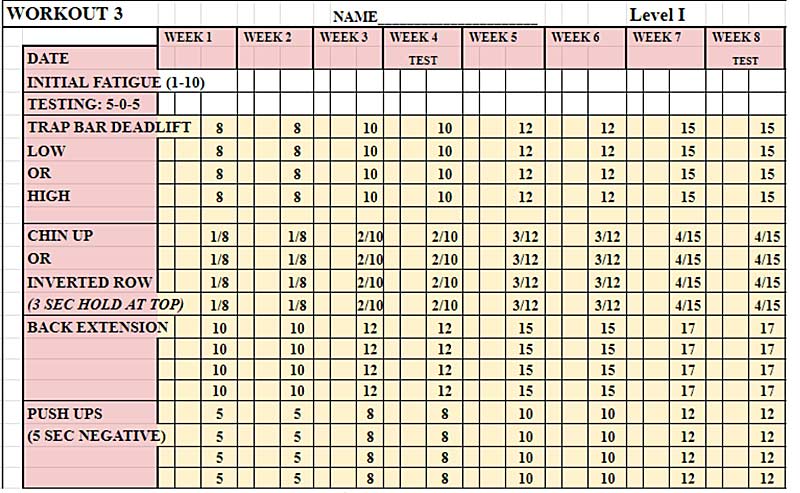

- Progressing volume. As we see in the sample workout program, volume for a newbie can be relatively low, and they will still grow muscle. As a lifter gets more experience, they will need more volume to see the same level of growth. Bodybuilders may use four, five, or even 10 sets of 10 repetitions of an exercise. For the muscle to keep adapting, the stress needs to keep progressing.

-

Adding weight to the bar is great; adding sets and repetitions to an exercise is also great. For the number of sets per body part per week, science points us to 10–20 sets being optimal for hypertrophy. If you start your athletes with 10 sets of chest or upper body pushes per week, this gives you room to progress up to 20 slowly.

- Closer to failure. While beginners can leave 3–4 reps in the tank per set and still see improvements in muscle size, your intermediate athletes will need to be pushed a little harder. Their body is used to lifting, and it’s not a big stressor anymore. The closer an athlete gets to failure, the more stressful it is on the body. Now they need to start pushing closer to 1–2 reps left in reserve per set. (As always, be safe with this. This should be done with experienced lifters, and failure should be technical failure—when their form starts to break down.)

- Rep ranges and lifting tempo. As we said earlier, any set that is within 5–30 repetitions and taken pretty close to failure has been shown to elicit the same amount of hypertrophy. With a beginner, we stayed within that 8–15 rep range, but now we can start applying new stress to the athletes. Twenty repetitions on squats or five heavy deadlifts will be a completely new stimulus to your athletes.

-

“The body will not grow unless it has a reason to. And the way to do this is through progressive overload and changing the stimulus.” –Charles Poliquin.

-

Workouts are allowed to consist of different rep ranges. Sets of five squats to start, then 10 reps of DB rows in the middle of the workout, and finish with 30 reps of push-ups, for example. Lower reps create more tension, and high rep ranges allow for more metabolic stress.

-

Speaking of Charles Poliquin, lifting tempos within .5–8 seconds per repetition all seem to elicit the same amount of hypertrophic signal. Poliquin wrote about 40–70 seconds per set, which I have not found any research on, but odds are, he was right as usual. So, if you have your beginners lift like an average person, where it’s about 1 second up and 1 second down per repetition, now is your chance to play around with slower eccentrics, slower concentrics (yes, your athletes are allowed to lift slow concentrically), and even isometric holds during a lifting repetition. This is a solid way to change up the stimulus and create more metabolic stress during a workout.

- More lifting days. Research shows that lifting three days per week is more effective for muscle growth than one.6 Spreading out the same amount of volume over multiple days (2+) helps the athletes use heavier loads on exercises compared to doing all of the volume in one day. Increasing the number of weekly workouts to three or four days will help with this.

Hypertrophy Adaptations for an Advanced Athlete

So now you have a few athletes who are advanced; they have several years of training at a high level and just need to put on a couple more pounds this off-season. This is a common occurrence with football players preparing for the NFL Combine—Tommy Tremble comes to mind. He arrived weighing 230 pounds and weighed in at pro day at 241 pounds. Along with all the performance goals that come with NFL Combine preparation, he also needed to gain weight to show he had the size of an NFL tight end.

With advanced athletes, you need to start adding in different angles and ranges of motion, utilizing mind-muscle connection and specialization training phases, and training to failure and beyond. Share on XTo accomplish this, all of the earlier rules still apply; those do not go away. With this level of athlete, you need to start adding different ranges of motion and angles, utilizing mind-muscle connection and specialization phases of training, and training to failure and beyond.

- Ranges of motion and angles. If you want the athlete to keep adapting, you must continue enhancing or changing the stimulus. You enhance it with load and volume and change it with new ranges of motion and angles. I know; I know—a full range of motion is the way to go for many different reasons, including hypertrophy. I’m not suggesting half-squat PRs for Instagram. Think of a standing DB bicep curl, now seated on a bench with a 45-degree incline, now chest down on a bench with a 45-degree incline. All of these are bicep curls, and as long as the elbow extends at the bottom and fully flexes at the top, it is a full range of motion.

-

For all three exercise variations, the humerus is in a different position relative to the body, and the athlete would be in different degrees of shoulder flexion and extension. We all know that the biceps attach to the scapula; therefore, the more the humerus is behind the torso, the more the muscle is stretched, and the more the humerus is in front of the torso, the more the muscle is shortened. By altering the position, you change how stretched the muscle is throughout the range of motion of the biceps curl. This is a common way to change up the stimulus and increase the stress of the movement on specific muscle fibers.

-

I do not view these as progressions, as one is not inherently harder than another. I view them instead as variations—ways to stress the muscle in a novel way. This is not just biceps curls either: think of humerus positioning with different triceps extensions or stretch on the hamstring when doing back extensions, 45-degree back extensions, and RDLs.

- Mind-muscle connection. Those bro-science bodybuilders were right after all—it works. Science has caught up and found evidence that the mind-muscle connection is more effective for hypertrophy than not using it. Who would have guessed that when you involve the brain in being intentional with what you’re doing (feeling a muscle work), it enhances the effect? What a concept. (We will see more of this with building strength and power too.)

-

In all seriousness, getting the athlete to feel a muscle working, getting the brain to—dare I say it—activate the muscle better, will help stimulate growth in that muscle. This mind-muscle connection is best with isolation exercises, but it can be used with compound movements as well.

- Specialization phase. The specialization phase is something we first heard of from Dr. Mike Israetel. Let’s say your workout program has a total of 100 working sets per week (four days per week, five exercises per day, five sets of each, for this example). In the specialization phase, you will allocate more of those sets to the body part you want to grow in your athletes and take some sets away from a muscle group you are okay with maintaining.

-

If their bench press is strong and they have enough anterior chain upper body mass, but you have identified that they need more hamstring size, take a set or two from bench and put it toward RDLs—or even take away an upper body press from one of your workout days and allocate those five sets toward their current hamstring regimen. A muscle needs a lot less volume to maintain size compared to growing; simply maintain a muscle group that is at an optimal size and spend more time stressing a muscle group that needs more growth.

- To failure and beyond. Yes, I heard Buzz Lightyear’s voice when I typed this. We know for muscle growth that we need to be adequately close to failure. Newbies can have 3–4 reps left, intermediates can have 1–2 reps left, and for advanced trainees, we need to push them to failure more often. (Same caveats as always: be safe, not for every exercise, not for every set of every workout, etc.) If you want your athletes to continue growing muscle, you need to continue increasing their stress. Doing the last set of hamstring curls until they can no longer complete a full rep is a new and hard stress. As a coach, you can even push them beyond their limit with high-intensity techniques (a phrase stolen from John Meadows):

- Drop sets. They do as many hamstring curls as possible at full range of motion, then drop the weight by 20% and perform more.

- Partial reps. They do as many hamstring curls as possible at full range of motion, then continue doing repetitions at half reps.

- Rest pause. They do three sets of 10 on hamstring curls. On the third set, have them do eight reps, then rest for 20 seconds. They do eight more reps, pause for 20 seconds, and then complete eight final reps. This last set consists of 24 reps at the same weight they used for 10.

- Force reps. Have them do as many hamstring curls as possible at full range of motion, then assist them through a full range of motion for five more reps, giving as little help as possible to complete each rep.

- Mechanical drop set. This one is easier to think of with a DB incline bench. Doing three sets of 10 reps, on the last set, have the athlete do eight reps. Then move the bench to flat and complete eight more reps with the same weight. Next, prop the bench up on two bumper plates so it’s at a declined angle and complete eight more reps. With each set of this drop set, you move the athlete into a more mechanically advantaged position.

These are methods we have used with athletes of all age ranges and experience levels to help them continue to grow muscle over time. Some of these methods can be used sporadically just to provide a new stressor and keep training fun for the athletes. Give them a drop set of biceps curls or hip bridges for their last workout of the week, and see how much fun they have with that.

We are aware that we work with athletes, not bodybuilders. These are tools you can use to stimulate muscle growth through the training career of your athletes, says @steve20haggerty. Share on XWe work with athletes. We are aware that the goal is not to create bodybuilders. These are tools you can use as a coach to stimulate muscle growth through the training career of your athletes.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Alex Roberts is the Strength and Conditioning Coach at R. Nelson Snider High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this role, he’s responsible for the year-round athletic development of all student-athletes. Coach Roberts’ main responsibilities are teaching strength training classes during the school day, leading after-school training sessions, and running the summer strength and conditioning program. He holds a Master of Science in Kinesiology and is CSCS certified through the NSCA.

Alex Roberts is the Strength and Conditioning Coach at R. Nelson Snider High School in Fort Wayne, Indiana. In this role, he’s responsible for the year-round athletic development of all student-athletes. Coach Roberts’ main responsibilities are teaching strength training classes during the school day, leading after-school training sessions, and running the summer strength and conditioning program. He holds a Master of Science in Kinesiology and is CSCS certified through the NSCA.References

1. Krzysztofik M, Wilk M, Wojdała G, and Gołaś A. “Maximizing Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review of Advanced Resistance Training Techniques and Methods.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019 Dec 4;16(24):4897. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16244897. PMID: 31817252; PMCID: PMC6950543.

2. Schoenfeld BJ. “The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2010 Oct;24(10):2857–2872. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3. PMID: 20847704.

3. de Freitas MC, Gerosa-Neto J, Zanchi NE, Lira FS, and Rossi FE. “Role of metabolic stress for enhancing muscle adaptations: Practical applications.” World Journal of Methodology. 2017 Jun 26;7(2):46–54. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v7.i2.46. PMID: 28706859; PMCID: PMC5489423.

4. Calatayud J, Vinstrup J, Jakobsen MD, et al. “Importance of mind-muscle connection during progressive resistance training.” European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2016 Mar;116(3):527–533. doi: 10.1007/s00421-015-3305-7. Epub 2015 Dec 23. PMID: 26700744.

5. Wackerhage H, Schoenfeld BJ, Hamilton DL, Lehti M, and Hulmi JJ. “Stimuli and sensors that initiate skeletal muscle hypertrophy following resistance exercise.” Journal of Applied Physiology (1985). 2019 Jan 1;126(1):30–43. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00685.2018. Epub 2018 Oct 18. PMID: 30335577.

6. McLester JR Jr., Bishop E, and Guilliams ME. “Comparison of 1 Day and 3 Days Per Week of Equal-Volume Resistance Training in Experienced Subjects.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2000 Aug;14(3): 273–281.