When thinking about sports-related injuries, many of us would first envision the violent contact injuries we see in American football. We’d think about the brutality and consequences of head injuries or the inevitable non-contact injuries we witness on Saturdays and Sundays while huddled around the TV screen.

Basketball has not conventionally been perceived as a high-risk sport or one that comes with significant injury risk considerations. Although basketball injuries are typically more discrete, we should not overlook the rigorous demands of basketball, as these athletes experience tremendous physical stressors in their own regard. In this article, I’ll cover the primary injuries for basketball athletes and discuss how we can take a preventative approach to mitigating their onset.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=14417]

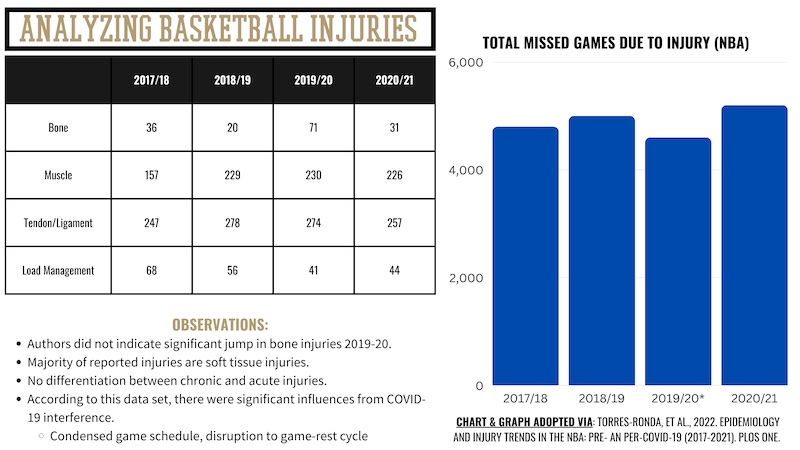

Basketball Injuries by the Numbers

Injury trendlines across all major sports have risen over the last decade, at least at the professional levels, and basketball is no exception. With the influence of early specialization, AAU leagues, and expanded practice and training demands, basketball athletes can become uniquely prone to injuries driven by accumulative repetitive stress. The compounding stress of a persistent high volume of court time can predispose athletes to chronic ailments such as tendonitis, muscle strains, and ligament strains.1

Additionally, taking into consideration the idiosyncrasies of basketball athletes—abnormal physical frame, high on-court volume model, and lack of variation in training—basketball can become a battle of attrition more than anything else. This may especially be the case at the professional level, which has a grueling 82-game regular season along with a demanding travel schedule.

As evidenced by the chart shown above,2 injuries in the NBA have been persistent, if not rising slightly, over the last five years. Also outlined above, NBA injuries are predominantly tendinous/ligamentous (soft tissue) injuries, followed by muscular injuries such as strains and microtears. While it was not explicitly stated whether these injuries were chronic- or acute-based, it is fair to speculate that given the constructs of the sport, basketball players are probably more susceptible to chronic injury types such as tendonitis, fasciitis, and compressive fractures.

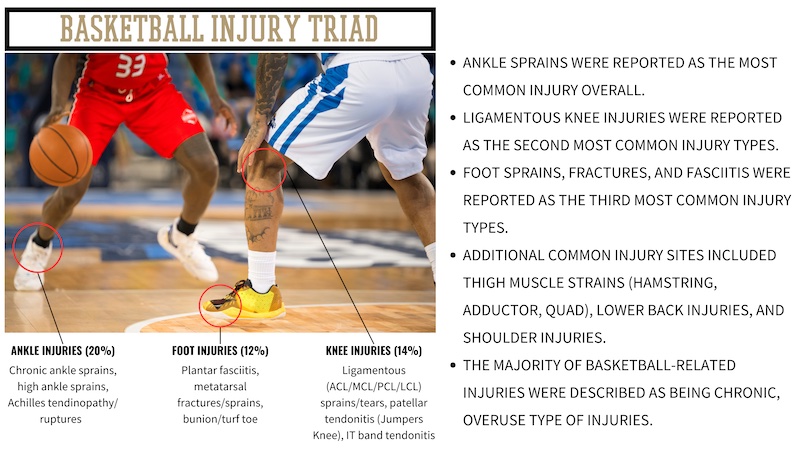

There is also a clear priority for injuries based on location, and likely to nobody’s surprise, that priority is from the knee down. According to data provided by Torres-Ronda,3 the most commonly injured site is the ankle (20%), followed by knee injuries (14%), and then foot injuries (12%). Collectively, injuries from the knee down account for nearly 50% of all injuries experienced by NBA players. Although hip (groin) and lower back injuries are somewhat common in basketball, the ankle, knee, and feet represent the triad of basketball injuries.

Preventative Strategies for Hoopers

As shown through the work of Torres-Ronda3 and others, the primary consideration with preventative strategies for basketball players is managing the work-rest ratios—specifically, the rate of change in physical demands. It has been well established that substantial changes in playing or practice time, along with rapid fluctuations in player demands, have shown to be the strongest factor in injury occurrence. Despite this being largely out of the control of the strength coach, it should be monitored closely. And although beyond the focus of this article, there are also the extraneous factors of sleep quality/quantity, nutrition, hydration profiles, and psychoemotional stressors that need to be accounted for when discussing injuries.

But from a mechanical perspective, several strategies can be applied to mitigate the onset of injuries. The predominant focal point for strength coaches, physical therapists, and athletic trainers working with basketball players is emphasizing qualities from the knee down. Additionally, analyzing the individual proportionalities of strength and mobility rather than the empirical, isolated outputs is another essential component for basketball players. While these athletes aren’t typically required to exert maximal force, there are a lot of nuances to how strength is expressed in basketball. This speaks to why we should look for more of an integrative rather than an overloaded foundation for programming.

Analyzing the individual proportionalities of strength and mobility rather than the empirical, isolated outputs is another essential component for injury prevention in basketball players. Share on X1. Improve Foot and Lower Leg Strength

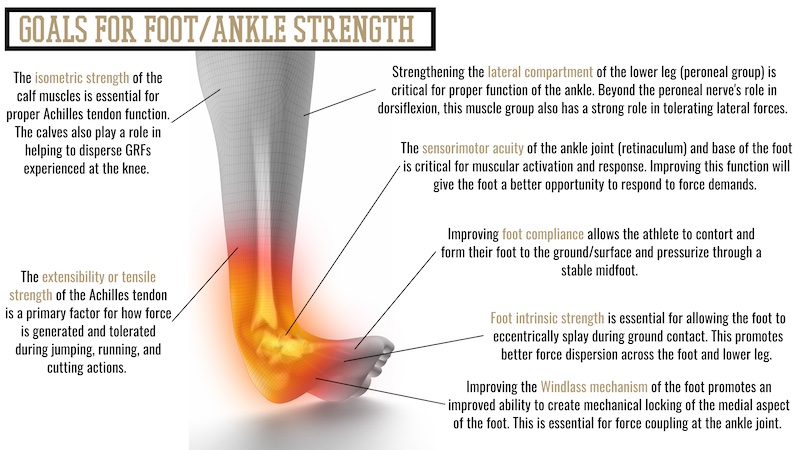

Considering the significant rates of lower extremity injuries, indirect applications simply do not suffice to meet the demands of these athletes. Deliberate work targeting the feet, ankles, and knees should be a foundational component of any basketball program. A simplified approach for strengthening the feet, ankles, and lower legs can be executed from four primary pillars:

- Strengthening intrinsic foot muscles.

- Developing foot compliance.

- Improving proprioceptive acuity.

- Improving the force coupling of the ankle joint (Windlass mechanism).

Improving strength and function in the feet and lower legs is relatively simple, requires no additional time or resources, and represents what I believe to be the lowest-hanging fruit available for most athletes. The added bonus to this is that by improving foot strength, sensorimotor acuity, and force coupling of the ankle, we also directly provide a better foundation for knee health. Given the knee joint’s simplistic nature and limited degrees of freedom, only so many things can be done directly to improve knee health. As such, improving the foundation for the knees (foot and ankle function) provides a better opportunity to preserve stress experienced at the knees.

Video 1. Foot Compliance for Knee Health

The bulk of my foot and ankle work falls at the top and bottom of programming—in other words, prioritizing feet and ankles during the warm-up/movement prep periods and finding ways to integrate these concepts into the accessory blocks. The simplest adjustment coaches can make is having athletes perform a portion of their training out of their shoes, which, again, for me, tends to fall in the movement prep and accessory periods. Having athletes perform a variety of isolated drills barefoot—such as a spring ankle series and rudimentary plyos—is a simple adjustment that provides a high return on investment.

Most of my foot and ankle work falls at the top & bottom of programming—prioritizing feet & ankles during the warm-up/movement prep periods & integrating these concepts into the accessory blocks. Share on XAdditionally, having athletes remove their shoes for standard accessory movements like single-leg RDLs, step-ups, and lunge patterns can provide great opportunities to get some barefoot work in. Beyond that, a lot of the mundane restorative work for feet and ankles can be prescribed as “homework” for the athletes so that it doesn’t take away from limited training time.

Video 2. Spring Ankle Series

Considering the amount of time basketball players spend with their heels off the ground, the demand for force coupling at the ankle joint is very high for these athletes. Improvement of force coupling at the ankle is rooted in the ability to create mechanical tensioning through the medial plantar arch, along with the ability to pressurize across multiple points of the forefoot (compliance). This is another thing that can be accomplished in training by slightly modifying how movements are performed. A primary application I use for developing the Windlass mechanism is a floating heel technique, where we have the athlete perform conventional movements like a front foot elevated split squat with only their forefoot on the box.

2. Close the Gap on Contractile vs. Connective Tissues

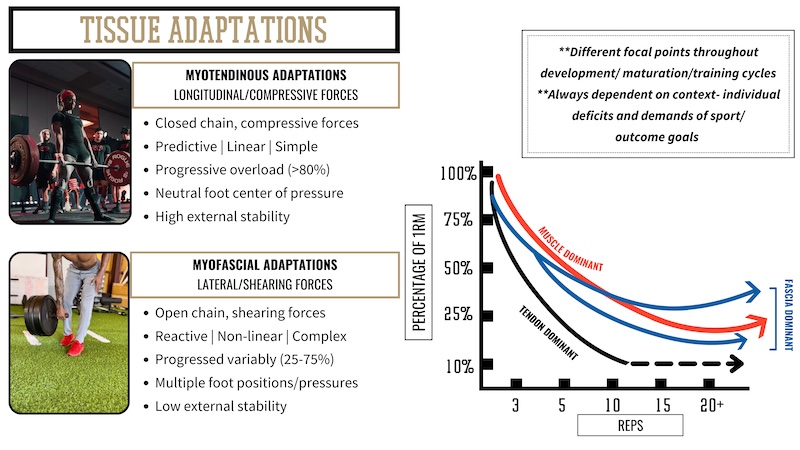

The majority of basketball injuries are classified as connective tissue injuries, which should prompt coaches to consider how their training parameters influence different tissue types in the body. Force profiling provides a convenient and objective way to discern significant differences between muscular capacity and soft tissue resiliency. This can be observed in a number of ways, for instance, with force plate analysis, which is becoming more widely accessible and practiced. Simple diagnostics to determine muscular versus connective tissue contributions and capacities include having athletes perform a multitude of jump types, such as static versus countermovement jumps, and analyzing traits like time on the ground versus flight time.

We can best decide between emphasizing contractile and connective tissue in training by analyzing the parameters in which exercises are prescribed and performed. For instance, where myotendinous adaptations occur at higher intensities (>80%) with a longer time under tension, myofascial adaptations are more aligned to submaximal intensities (60%–80%) and performed with higher velocity. We can also consider the type of load utilized or applied, as this can be a significant factor in determining which tissue type is being prioritized.

Most basketball injuries are classified as connective tissue injuries, which should prompt coaches to consider how their training parameters influence different tissue types in the body. Share on XIn addition to the intensity ranges, static load is preferable for emphasizing muscular and myotendinous developments. In contrast, isokinetic options like cable, Keiser, or band loading are generally ideal for emphasizing connective and myofascial tissues.

There are a few important distinctions to this part of the conversation, and the first is that these tissues are inextricable, and purely isolating a single tissue type is an impossible feat. Nevertheless, we can be selective to tissue type and preferential with adaptations when training parameters are applied in a specific way.

The second consideration is that one is not inherently superior to the other. The priority should be on the proportions between contractile and connective tissue and then considered based on the athlete’s morphology and play style.

If you have an athlete who is more muscularly driven, the solution in training isn’t to focus purely on developing the connective tissue but rather to seek better compatibility between the tissue types and work to close any substantial margins of deficit. Despite this being anecdotal, I feel strongly that a significant difference between contractile and connective tissue presents a major culprit for injury potential. The mistake several coaches have made is committing themselves to the blind pursuit of maximizing force while neglecting how that force expression is being elucidated.

3. Emphasize Integration, Not Overload

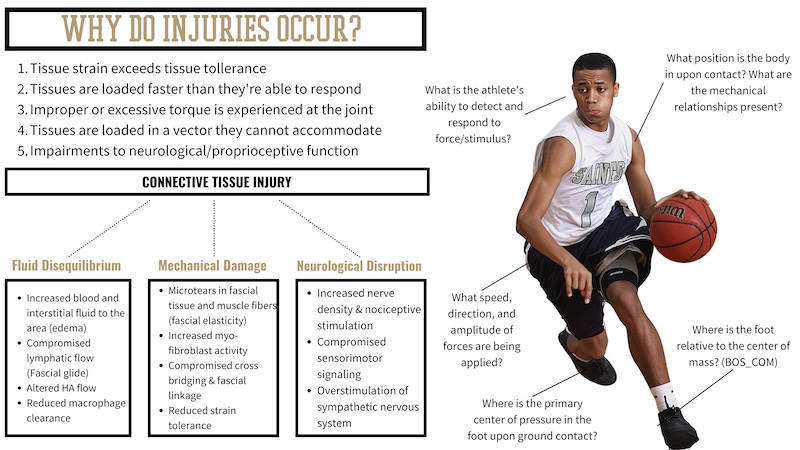

The primary factor in the occurrence of soft tissue injuries is tissues being loaded faster than they’re able to respond or in a vector (applying torque) they cannot tolerate. What’s important to recognize, though, is that injuries do not occur because of the failure of one specific tissue but rather are a consequence of supporting systems failing the tissue. Nothing about our anatomy functions independently; it is always a tandem of systems, tissues, fluids, and signals that occur in a dynamical, complex harmony. As this relates to training, having a detailed and precise strategy for emphasizing the relationships of these systems is critical.

What’s important to recognize is that injuries don’t occur because of the failure of one specific tissue, but rather are a consequence of supporting systems failing the tissue, says @danny_ruderock. Share on X

Emphasizing integration rather than pure overload is a training principle that I have almost inherently become ascribed to, especially in the case of injury. Utilizing an integrative approach does not mean that we become averse to high force loading; it does imply, however, that overload is a byproduct rather than a training priority. Additionally, I put an emphasis on utilizing movements that demand kinetic integration or sequencing. The time and place for pure isolated exercises is slim, and, for my sake, they’re not performed often. My focus is more aligned with how the athlete connects or performs movement and then looking to challenge these movements through a variety of progressions or “layers.”

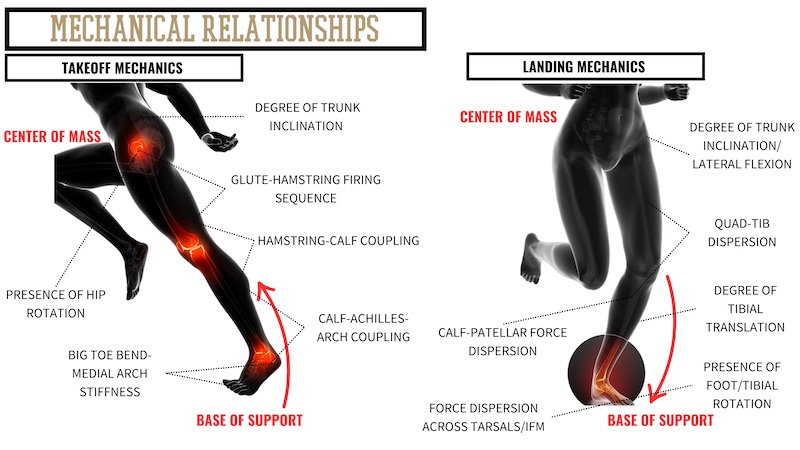

A priority for integrative training is to emphasize the mechanical relationships of movement. For the sake of foot, ankle, and knee health, there are several marquee relationships we can look to.

The first is the relationship, or interface, with the ground upon contact. Where the center of pressure is across the foot in relation to the direction of movement is a critical factor in the way the body will experience force. In addition to the position of the foot, the amplitude, rate, and direction of force are all also determining factors. From there, the ability of the foot to load eccentrically (splay) and the relationship between the base of support and center of mass will strongly influence the firing sequence of the associating muscle groups.

When athletes cannot create adequate force coupling around the ankle, knee, and hip joints, the joints become vulnerable to experiencing undue stress. There is also a significant influence from the presence of rotation: for instance, whether the foot is more supinated/inverted or pronated/everted. This changes the kinematic relationships of the lower leg muscles, which will then likely influence the bigger muscle groups of the thigh.

Similarly, the position and angulation of the trunk during dynamic actions will have a strong influence on the firing sequence of the leg muscles. This relates back to the relationship between the center of mass (COM) and base of support (BOS), where the greater the distance between the two, the greater the amount of torque experienced at the associated joints, namely the knee joint. For instance, when excessive degrees of ipsilateral trunk flexion are present during a single-leg landing, ACL injury risk increases due to the consequential dynamic valgus torque placed on the knee.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11142]

Key Takeaways

Basketball players have unique frames; beyond the overall height of these athletes, the limb length ratios are generally more of a factor in training than for athletes of other sports. In conjunction with the high-volume on-court time, this extreme length can make training challenging for these athletes and likely plays a significant role in injury manifestation.

Considering the high rate of lower-extremity injuries, prioritizing the feet and lower legs should be a staple of training basketball athletes, says @danny_ruderock. Share on XAlthough injuries are never entirely preventable, some strategies and modifications can provide a lot of value for preserving the health of basketball players. Considering the high rate of lower-extremity injuries, prioritizing the feet and lower legs should be a staple of training basketball athletes. Additionally, with the elevated possibility of connective tissue injuries, training adjustments should be made to account for the disparities between contractile tissue capacity and connective tissue resiliency.

By utilizing an integrative approach that is individualized to the athletes, we provide the athletes with a better opportunity to stay healthy and durable for the long term without compromising their performance in the short term.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Korkmaz MF, Cetin A, and Bozduman O. (2020). “Anthropometric evaluation of ratio between extremity length and body length in basketball player adolescents.” Pedagogy of Physical Culture and Sport. 2020;24(3):125–128.

2. Escamilla V, “Epidemiology and injury trends in the NBA,” Thermohuman.com, 2/22/22.

3. Torres-Ronda L, Gámez I, Robertson S, and Fernández J. “Epidemiology and injury trends in the National Basketball Association: Pre- and per-COVID (2017-2021).” PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2): e0263354.