[mashshare]

In the world of performance training, a needs analysis of the sport is mandatory—but this only represents the first step to a fully optimized training program. A coach must also look at the playing style of the individual athlete and the demands the athlete puts on their body to be successful on the court. Not all athletes of the same position will have the same playing style, and understanding this is important for designing and coaching a training program to optimize performance and injury mitigation.

This article features a case study on Darryl Wong to show the inner workings of a performance training program for a basketball athlete. Darryl (from Vancouver, BC, Canada) is a lifelong basketball player, former high school team coach, and current captain to two competitive amateur teams. He’s an athlete who continuously goes out of his way to improve, working with professional basketball coaches in Canada and overseas in Asia to sharpen his skills on the court. Off the court, I have been in charge of his physical preparation on and off for the last five years.

Despite working incredibly hard and developing a respectable shooting game in the last several months, Darryl is known in his leagues primarily as one of the best and most aggressive finishers in the paint—as can be seen in this video of his playing style. Darryl’s reliance on agility (change of direction ability plus reaction time and game IQ), power, and mid-air acrobatic moves tell me several important factors that will affect my training prescription for him:

- Single leg ground reaction forces are very high when he drives into the paint and tries to score.

- The core must be strong and possess reactive abilities to rebalance after making contact with a defender in the paint.

- Limb speed must match decision-making speeds mid-air (acrobatics).

- Landing mechanics, proprioception (ability to sense where the body is in space), lower leg strength, and resilience must be high to land safely after each play.

- Because of multiple previous ankle sprains, extra care must be taken to ensure re-injury does not occur.

These demands are specific to Darryl’s playing style preferences and injury history. For example, other players in the same guard position—even on the same team—may prefer a less contact-based style and favor a more catch-and-shoot approach, which comes with its own unique set of physical preparation demands.

How to Individualize Training Based on Position and Playing Style

Considering the factors identified in the needs analysis, what kind of training is the most suitable for Darryl? Let’s address each one of the five demands.

1. High single leg ground reaction forces while driving into the paint and trying to score

Simply put, Darryl must have adequate single leg strength and power to make this playing style successful. We develop this in our program through both bilateral and unilateral training at both low and high velocities.

Bilateral, low-velocity exercises include:

- Trap bar and conventional deadlifts

- Front and back squats

- Hip thrusts

Bilateral, high-velocity exercises include:

- Dumbbell and trap bar squat jumps

- Plyometric jumps (continuous jumps, depth jumps)

- Weighted countermovement jumps

- Multidirectional and rotational jumps

- Cleans and snatch variations

- Linear sprint drills

- Lateral and multidirectional cone agility drills

Unilateral, low-velocity exercises include:

- Multidirectional lunges

- Split squat variations (rear foot elevated, hand supported, dumbbells, barbells)

- Single leg deadlift variations

- Single leg hip thrusts

Unilateral, high-velocity exercises include:

- Single leg plyometric hops

- Single leg box jumps

- Single leg jumps (split squat jumps, staggered stance jumps)

- Explosive sprint starts in lunged, staggered stance position

- Lateral and multidirectional bounding

There’s a common misconception that, to achieve high single leg power, athletes must always—and only—train unilateral exercises at high velocities. While this satisfies the principle of specificity, performing a variety of bilateral and lower velocity work improves overall lower body strength (especially in the earlier stages of athletic development), allowing the athlete to fully reap the benefits of single leg power training.

All of the exercises listed above are included in the yearly training plan, while the intensity, volume, and emphasis of each category will vary depending on injuries, league season, and training phase.

For example, in the off- and pre-season (2-3 months before the season), we focus on building as much strength and power as we can with both bilateral and unilateral exercises. We also add sprints and drills to improve running and change of direction mechanics.

During the season, I generally take the number of exercises and the volume of training down a notch to keep recovery manageable. Our goal here is to maintain and possibly improve strength and power measures via low-volume means: high-quality weighted jumps, single leg plyometric jumps and hops, and high-velocity bilateral exercises like cleans and jerks.

Keeping the intensity high during the in-season is crucial to preserving the adaptations made in the off- and pre-seasons. I remove sprinting and agility drills because these movement qualities are already expressed and practiced during game competition; we can allocate the extra energy and training time more efficiently.

When I started training Darryl, he expressed that he wanted to become stronger on the court. His athletic profile reflected his assessment of his weaknesses: he had high reactive strength and performed very well in high-velocity situations and exercises but had relatively lower absolute strength. Our goal, then, was to improve his bottom line: low-velocity strength—essentially, build his overall strength base so he feels more resilient on the court and to supplement his power.

Specificity still wins, but not in the absence of building a foundational base. Share on XThe results were evident when both his vertical jumping ability and agility improved through strength work and minimal high-velocity power training. That was years ago. Currently, high-velocity power training is very much part of the program—specificity still wins, but not in the absence of building a foundational base.

2. Core strength and reactive ability

Core stability drills activate the nervous and musculoskeletal systems. We can’t sufficiently build stability and strength through low-intensity exercises like bird dogs and dead bugs, although I still include these in the program as a warm-up to the main work.

Our program develops general core strength through the main compound lifts like deadlifts, squats, pressing, bent rows, and Olympic lift variations. We supplement these with more specific exercises like offset loaded exercises, reactive Pallof presses, rotational medicine ball training, weighted isometrics, and loaded carry variations.

Regarding strength on the court, both core and lower body strength are critical. The ability to become an unstoppable attacker depends on the athlete’s ability to:

- Root their feet into the floor to push

- Possess a rigid core to prevent power leaks

- Push back on defenders

3. Limb speed must match decision-making speed in mid-air

Whether switching hands for the layup or faking a pass before the finish, mid-air acrobatics are part of Darryl’s game. In physical terms, he must have sufficient plyometric ability in his upper and lower limbs to change directions in mid-air.

Since Darryl already performed this at a relatively high level before I started working with him (through basketball training and his natural ability), my job was to supplement this talent. I used plyometric exercises like assisted clap push-ups, plyometric inverted rows (where the hands release at the top of the pull), continuous medicine ball slams, continuous plyometric box jumps, and plyometric medicine ball tosses. The overall goal is to develop his nervous system by making him think and move fast.

[vimeo 334165701 w=800]

Video 1. Plyometric exercise, such as the one demonstrated in the video, supplement Darryl’s natural mid-air acrobatic talent.

When I prescribe these exercises, I have a set x rep scheme in mind, but the one rule I follow is to stop when the quality of repetitions decreases significantly. Through practice and communication of expectations, Darryl has developed a high standard for quality reps. My philosophy here aligns with power endurance protocols: fast, high-quality reps achieved through short, numerous sets.

4. Landing mechanics, proprioception, lower leg strength, and resilience must be high to land after each play safely, and

5. Due to multiple previous ankle sprains, extra care must be taken to ensure re-injury does not occur

Producing large ground reaction forces play after play, game after game, and season after season results in wear and tear on the muscles and joints in the lower limbs. Injuries occur when the system’s capacity is not sufficient to deal with the demands placed on it. Unfortunately, Darryl sustained multiple ankle injuries back in his high school days that have impacted his ability to train and recover between games. A large part of our training has addressed this because I believe an athlete is at the mercy of their weakest link.

Ankle injuries, specifically, result from several factors separated into two categories:

- Contact injuries. Examples include bad landings resulting from stepping on another player’s foot or being pushed off balance mid-air (after driving in or after a jump shot).

- Non-contact injuries. These include injuries sustained from improper landing mechanics after jumping and poor proprioception and weak reactive strength in the foot and ankle complex during change of direction and landing.

Ankle injuries caused by interrupted landings occur from the recreational level to professional basketball. Contact injuries are largely unavoidable because they are out of the athlete’s control, although the player’s preferred playing style can reduce or increase their likelihood. Nevertheless, we can still take steps to cover our bases and mitigate injury risk (more on this in the examples later).

The good news is that the two variables related to non-contact injuries are highly trainable. With Darryl and the other basketball athletes I work with, we improve landing mechanics and foot and ankle complex strengthening through a variety of means. This begins with educating the athletes on the concepts behind eccentric force absorption and the role of foot strength in jumping, so they can not only internalize the training we perform together off the court but also apply these tools to their game on the court. We also perform specific exercises to help develop force absorption and lower leg resiliency.

- Eccentric force absorption. To train eccentric force absorption, we perform box step-off and jump-off landings and vertical jump and reach landings (mimicking a layup or rebound) and introduce the depth jump when the players are ready.

- Proprioception and reactive strength. To develop proprioception and reactive strength in the ankle and foot complex, I prescribe multidirectional single leg hops (jump and stick the landing drill).

[vimeo 334166122 w=800]

Video 2. This video shows a variation of a single leg hop focusing on lateral stability performed by Darryl’s teammate Charly.

Charly has also dealt with ankle injuries, both minor inversion and eversion ankle sprains. Adding this exercise to his training regimen as a warm-up has helped him tremendously.

Overall, these drills serve as a great way to warm up for the compound lifts and high-intensity jumps because they “wake” the athlete up without taking away from force production later in the session. I also have my athletes perform these without shoes—barefoot—to strengthen the intrinsic foot muscles.

Foot training has improved agility and plyometric ability for basketball players, martial artists, and racquet sport athletes. Share on XFascial training is not a big driver in my training prescription, but I do believe in the feet-glute fascial connection and having strong feet. I’ve seen positive results using foot training with basketball players, martial artists, and racquet sport athletes as it relates to agility and plyometric ability. However, I still preach that it’s merely a supplement to the meat and potatoes of any effective training program.

As I alluded to earlier, contact injuries are unavoidable, but we can still take steps to mitigate the risk. Two drills I want to highlight are the partner-directed single leg hops and reactive jump landings. In both drills, contact from the partner adds randomness to the training environment, forcing the athlete to adjust accordingly. By introducing an external stimulus, the athletes develop their ability to stabilize and absorb force reactively. While this doesn’t exactly mimic in-game conditions, it does train proprioception in a reactive, safe, and replicable manner.

[vimeo 334166485 w=800]

Video 3. The athlete hops on one leg while his partner controls his direction, adding randomness.

[vimeo 334166868 w=800]

Video 4. The athlete reacts to pushes by his partner while performing jump landings.

Case Study and Results—Darryl Wong (Before Sept 2018 Season)

In the pre-season leading up to Darryl and his team’s 2018 Fall season, I put many of these training principles and methods to the test. Since he had chronic ankle soreness from practices, our key goals in the pre-season were to improve:

- the health and strength of the ankle and foot complex

- key measures of agility using closed and reactive drills

- lower body strength

The eight-week training cycle consisted of two weight room sessions and one on-court session per week. Weight room sessions focused on building full body strength and power through compound lifts, plyometrics, and jumps training. The on-court sessions consisted of plyometric hops, reactive agility drills, short sprints, and basketball-specific conditioning training.

I created a pre- and post- training test to include a lower body strength test, an upper body endurance test, the pro-agility 5-10-5 test, and two tests included in the NBA combine: the lane agility test and ¾ court sprint test. These options reflected the demands of the athlete’s playing style, and improvements in these would give me a good indication that Darryl would be a better athlete on the court.

After eight weeks of training, we saw sizeable improvements across the board, both subjectively and objectively. Darryl reported feeling stronger and more resilient on the court during practice and scrimmages, reduced markers of ankle swelling and pain, and more responsive feet during a change of direction (crossovers, driving, etc.).

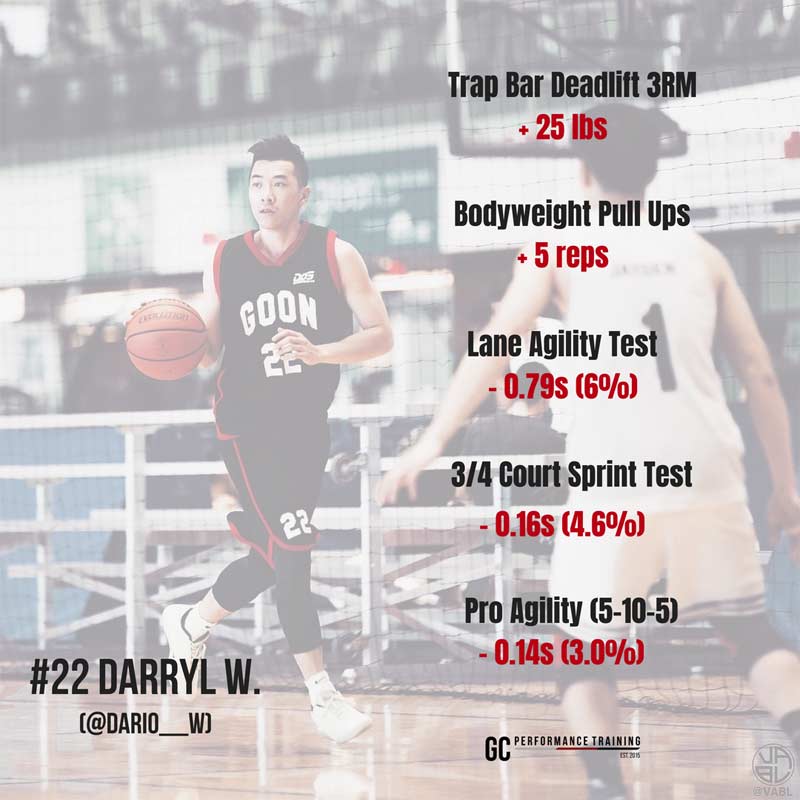

Objectively, his trap bar deadlift 3RM increased by 25lbs over the eight weeks, he added five reps to his bodyweight pull up, and improved his agility test scores 3-6%. Four other players on the team also saw improvements in all of the strength and agility tests.

Darryl and his team ended off the Fall 2018 season with only one loss and ended up clinching second place in the playoff finals. As of the time of this writing, Darryl and his team are headed into the Spring 2019 playoffs undefeated and as the number one seed.

Conclusion and Takeaways

The biggest takeaway from this article should be to dive deeper into the details of the athletes you’re coaching and training. Instead of only performing a needs analysis on a basketball player or position, understand the individual’s playing style and the associated demands and consequences that come along with that style.

Dive deeper than a needs analysis to understand an individual's playing style and the associated demands and consequences of that style. Share on XI also use many of the exercises and methods discussed above with other basketball players who each have different strengths, weaknesses, and playing styles. However, I mold the training program, exercises, drills, cues, and recovery modalities to the individual player. This is what true performance training optimization and injury mitigation are about.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]