Unlike many field and court sports, football, out of season, traditionally has less skill development—especially in the area of small-sided games (SSGs) and agility training methods. This lack of specificity leads to increased injury rates, specifically in training camp, which is the onset of high exposures to those missing training elements in the off-season.

To prevent this, small-sided games should be implemented in the lead-up to the competitive season. This ensures the first time there are bodies flying and ensuing chaos isn’t in the players’ first team practice but in the off-season in a controlled environment. In this segment of my series of SSG articles, I introduce the reason for creating specific mailboxes based on positions, reinforced by GPS data that aims at attacking the training void between general training and specific training as it pertains to American football.

The use of small-sided games ensures the first time there are bodies flying and ensuing chaos isn’t in the player’s first team practice but in the off-season in a controlled environment, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XAgility and small-sided games are two important components of sports training. Agility refers to the ability to change direction quickly and efficiently in response to the environment, while small-sided games are modified versions of traditional sports that involve fewer players and smaller playing areas. Incorporating both training concepts into an off-season program will decrease the shock that comes with the chaos of play and lessen the chance of injury. In the previous article, I discussed the elements of play and factors that go along with increasing training specificity as the competitive season approaches.

How many of these elements to incorporate—and how frequently—will be based on GPS data that allows us to create SSG templates that fit position mailboxes so that sessions can flow and be efficient while preparing the players for the specific demands of their position. While we must incorporate the general training elements of agility—deceleration, acceleration, top speed, change of direction, and reaction time—to ensure increases in game play occur, understanding through the data which element needs more time will be a priority, as we don’t want to reach a point of diminishing returns within that positional mailbox.

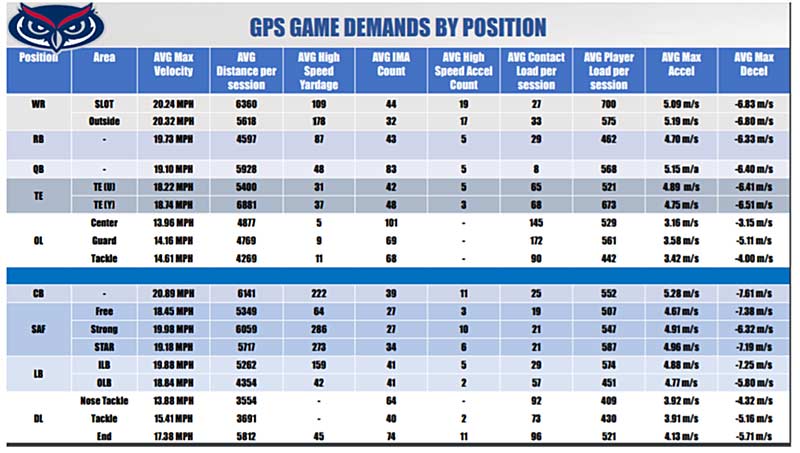

Corners don’t need three exposures to collision prep in a session, just as linemen don’t need 120+ yards of max speed distances. I have made the mistake of prescribing elements of training to populations that rarely encounter those elements in the game, which took away from some of the main training themes necessary for increased performance for that athlete at their position. GPS allows the prescription to be precise and takes the guesswork out of the application of SSGs.

Creating the Playing Field Based on GPS Values

In the world of strength and conditioning, the word “conditioning” seems to be associated with the ideology of long, boring, tedious, and plain running sessions. When defined, “conditioning” means “to train or accustom someone or something to a certain state.” So, conditioning can be any type of training and is not confined to just running extensive tempos.

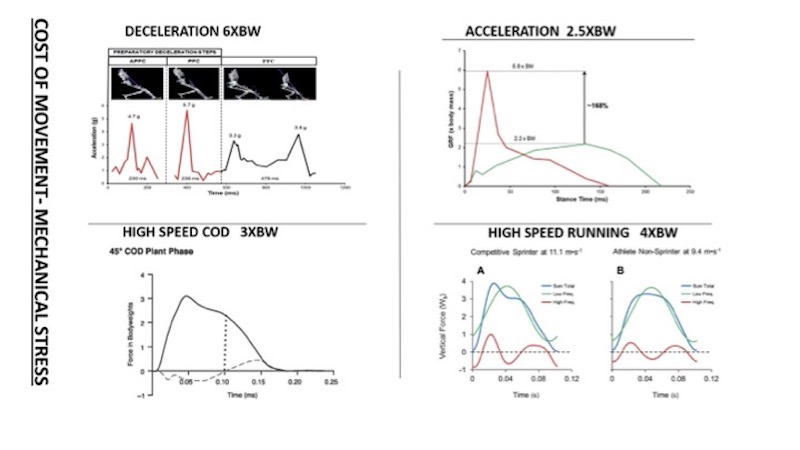

Throughout the evolution of the profession, conditioning became more synonymous with the cardiovascular adaptations of long-distance running and less synonymous with the physiological adaptations associated with exposure to the session’s mechanical stresses. Extensive and intensive tempos serve a purpose in times of general training but do not alone build the specific qualities to be prepared for in the chaotic and mechanically taxing demands of play.

Repeat sprint ability sessions are also valuable but, yet again, miss the agility and specificity of play. To go from such broad and general training to claiming players are “in shape” and “gameplay ready” is irresponsible. Small-sided games can move strength and conditioning coaches from very boring and general training sessions to enjoyable and specific sessions that actually prepare the players for game play. The metaphor “you have to walk before you run” holds true as we, as coaches, don’t want to go from these extremely rigid and structured running workouts to literally an entire unpredictable environment that involves car crashes on every play like football provides.

What is the purpose of conditioning? Conditioning is meant to prepare the athlete for the physiological and mechanical demands of their sport. Coaches check the box on the physiological side more times than not but miss epically on the mechanical side.

Tissue stress capacity is real, and the preseason epidemic of soft tissue injuries should drive home this point. Traditional models of conditioning lack the specificity and requirements SSGs provide to help zoom in on the mechanical and psychological factors of the game. Small-sided games are defined as a reduction in players or field size from regular game play, which American football uses in practice with inside run, 7-on-7, and even tackling drills. The use of SSG does not have to end once the season is over. In the off-season, it is critical to continue the skill development that results from exposure to SSG.

Using reduced field space in evasion/tracking drills allows players to focus on their position and gets them valuable reps in a scenario that occurs frequently in game play while increasing robustness to the mechanical stress associated with the cost of movement. In this article, we will piece together the why behind the design and volumes associated with off-season small-sided games. We will then look at the how when we explore the progressions of drills that climb the continuum from general to specific.

Big Rocks

Before going to the microscopic levels of stress that GPS shows, every coach should start with the needs analysis for football’s basic game characteristics when constructing the specificity of SSG in the off-season. Understand that practice duration and game duration are critical pieces of information that play an essential role in overall workload distribution.

After how long the game or practice is, the type of playing style is the next pertinent piece of information that must be discussed and understood. A hurry-up offense and a huddled offense are polar opposites from the standpoint of energy demands. This search for why by your coaching staff on principles of play will increase organizational communication and buy-in because, as the strength and conditioning coach, you’re trying to give the sport coach exactly what they want by optimizing your training to enhance their style of play.

Understanding the average time between plays can help piece together the physiological demands of play for your team. Knowing the average play count in a game and plays per series will help identify what level of reps are appropriate for off-season conditioning and practices.

You Wouldn’t Drive a Car Without a Dashboard

Technological advancements within the sports world have dramatically increased the precise explanation of game play and what players experience during every play and game. GPS is now to athletes what a dashboard is to a car. You wouldn’t go on a road trip without knowing your car’s oil level or how much gas is in the tank. The same goes for football players.

How do coaches plan practices without knowing how much volume players accumulate through total yardage, high-speed yardage, and acceleration load? The first time we used GPS at a practice, it was shocking to see how far we were off on the lower estimation of total yardage compared to what was really going on, and it was reflected in our planning in the off-season. Flat out, we underestimated and saw a huge workload spike going from the off-season to the in-season, which is not ideal.

Through data from GPS and research papers, any coach can now baseline practice averages for several metrics. There is no excuse for not knowing what is truly going on in the game at any given moment.

The GPS doesn’t only give the coach a detailed explanation of playing stress; for us, the data has really distinguished the different demands between positions. Understanding that football is a game of many games and positions with drastically different demands helps strength coaches create accurate conditioning sessions with merit and purpose behind their execution.

Zebras

When I speak about training and planning for football, I love to utilize the zebra metaphor. When a person looks at a pack of zebras, there are very noticeable similarities between them:

- They have black and white stripes.

- They look similar to a horse or donkey.

- They run with very similar gait patterns.

When you observe this pack of zebras more closely, however, many individual differences stand out, such as:

- Different stripe patterns.

- Different sizes.

- Different running patterns.

Like the zebras, football looks very similar from a distance in terms of running, collisions, and formations, but when observed through GPS, the game is very individualized to each unique position. When building out SSGs for the off-season, it’s extremely important to mailbox players into specific workload categories that will be comparable to the unique demands exhibited by their position.

As much as I would like to individualize every player’s conditioning plan, that is extremely impractical from a resource standpoint. Mailboxing positions by body type, movement signatures, and load enables the strength and conditioning coach to customize enough of the session to where there are noticeable differences in the session position-to-position. Without this data, it is very easy to make mistakes with intensities, modalities, and volumes when prescribing conditioning. There is no need for a 300-pound lineman to run over 3,500 yards in a conditioning session when the max amount they run in an average practice will be 2,800–3,200 yards. Giving the athlete what they need based on data and not just feel will provide you with a sniper’s view instead of a shotgun approach.

Four Subgroups

Based on similarities in game demands and anthropometric averages, we have created four subgroups that determine drill selection, distances, and overall total load when constructing our SSGs in the off-season. This mailboxing process allows us to check a lot of boxes from a mechanical and physiological standpoint while maintaining a competitive atmosphere, as the players in these subgroups tend to interact on the field frequently. Coaches utilizing these subgroups can control and customize each drill to fit the positions’ needs.

The four subgroups are:

- Tanks/Bigs: Interior Defensive Line/Offensive Line

- Pickup Trucks/Big Mids: Tight Ends/Outside Linebackers/Defensive Ends

- Hellcats/Speed Mids: Running Backs/Boundary Safety/Quarterback/Inside Backer

- Motor Bikes/Skill: Defensive Backs/Wide Receivers

Tanks: Interior Defensive Line and Offensive Line

In any given game or practice, the big guys up front go through 40–60 car crashes. We label them “tanks” because of the similarities in their need to handle body damage, their maneuverability, and the power of their offensive strike. It is in these big guys’ job description to “kidnap” people, meaning they have to take another player and move them against their will.

These big boys play in a 5-yard box and rarely go over 3,500 total yards in a game or practice. Their total yardage will be around the 13,000-yard mark for an average game week. The position does require extreme quickness, strength, and agility because of the lack of space and inability to fix a mistake due to the minimal time and limited space.

These tanks have extremely high acceleration loads because of the rapid decels and changes of direction that occur on each play. Their acceleration loads rival skill players due to the movements’ frequency, not necessarily their intensity. Wide receivers stop at -7 m/s but only do it 13–20 times in a practice, while these tanks will stop at -3 m/s but do it 100 times in a practice.

The top speed of these tanks in game play is around 13–16 mph. They rarely accumulate high-speed yardage over 16 mph, so their main stressors come from short quick accels, decels, and collisions. Their average peak acceleration is around 4 m/s, and average peak deceleration is around -5 m/s.

Pickup Trucks: Defensive Ends, Tight Ends, and Outside Linebackers

This group commonly gets the wrong prescription of conditioning volume, both below average and above average. Because of their versatility, these “pickups” cover a large amount of ground in games and practices, which is reflected in total yardage and high-speed yardage. They fit the pickup analogy well, as they have to travel great distances but also have to be tough enough to handle the violent nature of game play in the trenches.

On average, this group covers between 5,000 and 7,000 total yards in a practice and game. This stems from running routes, pursuit, and special teams. They play in a 20-yard box. Their total yardage in a week reaches over 28,000 yards.

Even though there is a high running volume, pickups also experience roughly two-thirds of the total collisions of the tanks. They also get high-speed running between 50 and 80 yards per practice/game. Acceleration loads are usually higher than the team average due to the impacts and high movement volume. Peak speeds sit around the 19 mph range, with peak accelerations around 5 m/s. They sit in that 11–16 mph zone for the majority of game play. Deceleration loads are less than that of tanks but more intense, with peak decels coming in at -6 m/s.

Hellcats: Inside Backers, Running Backs, Down Safety, QB

This group of players fits the hellcat analogy because they must be extremely agile and fast. They play in a 20-yard box dominated by short, violent accels, decels, and changes of direction. They experience one-third of the collisions that the tanks get, so training to have body armor is still necessary, but much of their gameplay stress comes from the mechanical stress associated with agility.

On average, this group covers between 5,000 and 7,000 total yards in a practice and game. This stems from running routes, running plays, pursuit, and special teams, which are similar to the pickup trucks. Their total yardage in a week reaches over 28,000 yards. Hellcats’ acceleration loads sit in the middle of the pack in terms of total volume. Peak speeds sit around the 19 mph range but creep up into the 20 mph at times, with peak accelerations around 6 m/s. They sit within that 13–18 mph zone for the majority of game play. Deceleration loads are less than that of tanks but more intense, with peak decels coming in at -6.5 m/s.

Motor Bikes: Wide Receivers and Defensive Backs

These players have to be the fastest and most agile things on the field. They play in open space a majority of the time and experience the highest intensities of deceleration and acceleration. We have recorded peak decels at over -7.5 m/s and accelerations at 6 m/s. Their movement stress is the highest, their total movement volume is also the highest, and their collision volume is the lowest by a lot.

Our WR, on average, covers over 7,000 yards a game, with their acceleration loads topping the charts well above all other position groups. Game play is from 15–19 mph. Peak speeds exceed 21 mph. This group has to be able to tolerate high weekly running loads that reach well beyond 32,000 yards.

Drilling Down

The purpose of this article was to give the specifics of why I program and progress the drills I will outline in the next article. GPS has illuminated the fact that football is a game of many games. Even though game play falls under the same sport, the stress isn’t even close when looking at mechanical outputs. Having the data supports the mailbox approach outlined above to provide the players with what they need to be ready for actual game play.

GPS has illuminated the fact that football is a game of many games. Even though game play falls under the same sport, the stress isn’t even close when looking at mechanical outputs, says @CoachJoeyG. Share on XThis supports the application of SSGs over general and traditional conditioning methods closer to the competitive season. The next article will be the how, outlining how to model and progress from general to specific based on the GPS data provided here.

Lead Photo by Jason Mowry/Icon Sportswire.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF