Picture this: You’re at a conference, and you know it’s an S&C seminar because there are a lot of oversized humans squeezed into khaki trousers they aren’t used to wearing. This might be one of the only times you see these people out of shorts. A speaker is presenting—a legend of the industry—but to be honest, their material isn’t that different from when you saw them speak a couple of years back.

Afterward, you go to sit at the table with the guys you know and enjoy their company, sharing the same stories you all told last year. You go to the bar to strike up a conversation with someone, but somehow, you’re once again agree-debating about which squat variation is best or why Olympic lifting is overrated. You go over the same arguments before turning in.

The next day, you tag some of the big names who were there on social media and enjoy the rest that the conference has to offer before heading back to your facility. On the journey home, you reflect on what you’ve learned, and you struggle to truly justify the weekend’s value to your director when you’re back. You came away stimulated, but a week later, not much has changed in your practice, and you settle back into doing the same things you’ve always done.

Sound familiar?

Dollar for dollar—or hour for hour—sometimes the whole conference CPD (continuing professional development) experience can leave you wanting for actionable, direct change and growth in your own practice. This isn’t to say that’s always the case; some conferences are fantastic learning and networking opportunities that further learning and broaden educational horizons. However, the passive conference experience—pay (lots of) money, get accreditation points, let everyone on social media know you were there, go home—likely doesn’t represent an efficient use of time or value for money when it comes to actually getting better.

When we program for our athletes, we’re deliberate and purposeful with what we do, so why shouldn’t our approach to furthering our own learning be the same, asks @peteburridge. Share on XWithout wanting to sound preachy, if a big conference once or twice a year is what you view as furthering your own knowledge, you probably aren’t thinking big enough when it comes to bettering yourself. When we program for our athletes, we are deliberate and purposeful with what we do, so why shouldn’t our approach to furthering our own learning be the same?

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9062]

How Can We Do That?

Well, first and foremost, you must truly own your own development. Take responsibility for “getting better at getting better.” We can bemoan a shallow conference experience or the sheer volume of information out there being paralyzing…or we can actually do something about it. This is the difference between being passive and being purposeful in furthering our own learning.

With so much information available and everyone so readily connected (if you can count someone you’ve never met on LinkedIn wishing you a happy birthday as a “connection”?!), it has become much easier to access expertise and engage in dialogue to grow our practices. However, with so much out there, sometimes it can be hard to filter the signal from the noise.

Dan Pfaff once said, “We are swimming in a sea of knowledge, without the life jacket of wisdom to keep us afloat.” This is exactly what it feels like sometimes when you go on Twitter! Having purposeful strategies to further your learning can make the process much more efficient and cost-effective.

Here are a few of the strategies that have helped me get better at getting better. Have a look and see if these can help you too so that when you look back, you can say that you have had over 10 years of experience rather than 10 one-year experiences!!

1. Adjust Your Attitude

The first step toward upgrading our practice is changing our attitude toward self-improvement. This usually starts with a strong dose of humble pie, admitting you have much to learn. Nothing is worse than being the guy high up on the Dunning-Kruger curve, thinking you know everything!

The Japanese have a concept of “Kaizen.” The word means continuous improvement—and it is a word incredibly relevant to coaching. Coaching is a never-ending process of evolution and refinement. Any time I ever think I’ve got it all figured out, I remember a quote I heard from one of the lockdown Zoom-athons (a time when everyone seemed more open to personal development, almost to the point of Zoom CPD call fatigue!). In it, Loren Landow spoke about the acronym “SAS,” which stood for “Still Ain’t Shit.” It means that it doesn’t matter what letters you have after your name or which teams you’ve worked for—the athlete doesn’t care; they just want the best you can give them.

To do that, you must continue to sharpen your own sword. For those who want to truly achieve this, it is imperative to accept the vulnerability of not knowing, be open to challenge, and, more than anything, be curious to know more about what we are lucky to do.

I once accessed help from a coach educator who made me analyze footage of myself coaching using a GoPro, tracking what I said and how I cued. It was excruciatingly awkward watching the footage, and I was a bit embarrassed watching it, frankly. But if we ask our athletes to be comfortable being uncomfortable, shouldn’t we do the same?

If we ask our athletes to be uncomfortable being uncomfortable, shouldn’t we do the same, asks @peteburridge. Share on XThis process made me realize I talked too much and didn’t give my athletes space to fail, as I was trying to be heard all the time, likely reducing the level of learning going on. I gained a better understanding of the language I used and am less likely to fall into the trap of over-coaching.

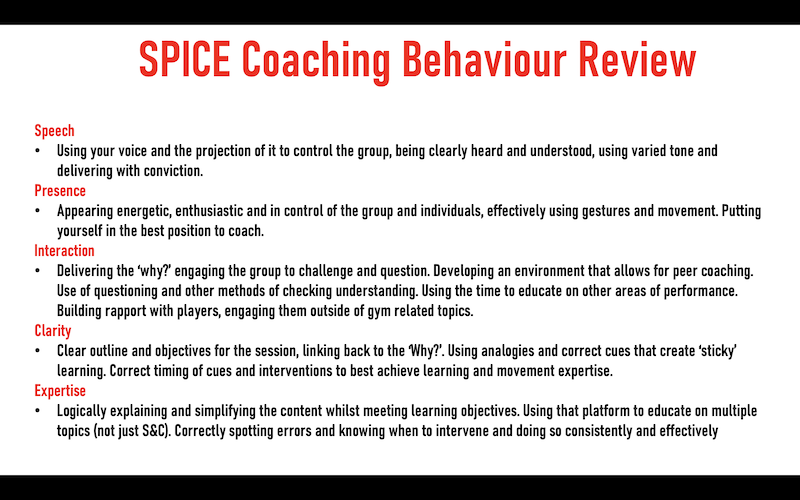

I now use a self-evaluation tool that I adapted from the world of teaching and melded into an S&C context to critically evaluate my sessions. This has led to me being a lot more deliberate with what I see, what I say, and how I say it.

I worked with a coach a few years ago who, in his first meeting with the playing group, said that the team wasn’t performing and may not be good enough right now—not the most positive of starts! However, after this somewhat somber opening, he accepted that this was where we were, but it was okay because the playing group was going to learn faster than anyone else, and it was more about what we were going to become. After a rough start, they won the league two years later.

On reflection, this approach of being brutally honest—admitting that some things aren’t good enough but that this is acceptable as long as you get up to speed quickly—can be comforting when you realize there are knowledge gaps in your own practice. Shaky on your ability to coach cleans? Don’t control large groups very well? Unsure of how to program conditioning sessions? Rather than being seen as an area of weakness, that attitude adjustment allows you to turn it into a fantastic opportunity to grow.

2. Hunt Down the Experts

Knowing what you don’t know is the first step, but action is required to determine how you can improve those knowledge or skill gaps in your practice. Everyone learns differently, and many mediums are available to capture some of that wisdom to keep yourself afloat.

One of the easiest ways to start is to ask: “Who in this area is good?” or “Who do I know who knows more about this than me?” From there, you can decide how to best access the learning you are about to embark upon. A few tools can help in this area: If you’re a bookworm, a quick search of available textbooks might help. If you’re more science-y, utilizing sites like Research Gate or Google Scholar to find journals is a good way to dive straight into the research. At the very least, you can find out who is studying/publishing within this area a lot.

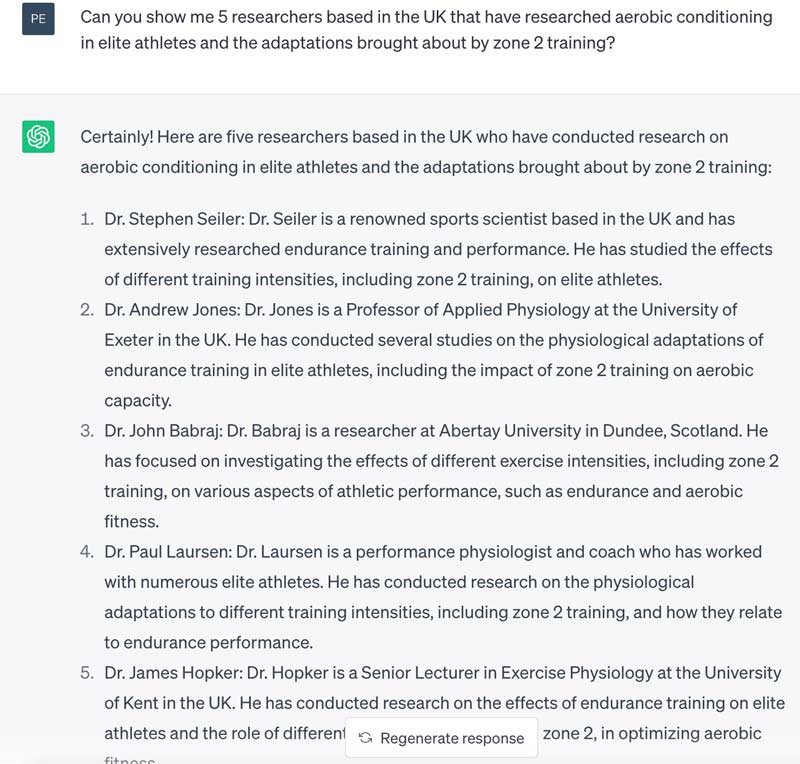

For a less academic entry point, finding those thought leaders on social media and following some of their work is an easy way to start filling that knowledge gap. Quite often, these people post helpful videos, presentations, or infographics. For example, Yann Le Meur has cornered the market on making infographics that sum up research papers. Jurdan Mendiguchia now takes his studies on changing sprint mechanics and uses short videos to get the main points across. For a more modern approach, you can use AI tools such as ChatGPT to guide you to expertise—you can even use it to geolocate the experts who are more local to you!

A recent example from my own learning was isometric training. I knew a bit about it, but I needed to know more before I had any chance of utilizing it effectively with my athletes. I started with an article by Alex Natera, then read a few chapters by Cal Dietz, before enrolling in an isometrics course that exposed me to other people who were already implementing it within their practice. I felt comfortable enough with the “why?” to experience more of the “how?” so I started adding run-specific isometrics to my training. Having stress tested it on myself (picking up cues, knowing the software, seeing the results, etc.), I was in a much better position to use it confidently with my athletes.

3. Set Up CPD Calls

If you are looking for a more interactive experience, direct CPD calls or chats can be a fantastic way to kick your learning into overdrive. Once you know which people have knowledge in an area, and you are curious to know more…reach out!! It continues to surprise me how much bespoke learning you can do by reaching out to experts and asking good questions. On numerous occasions, researchers have been more than happy to share their work and insight, and they quite often love hearing how it might be applicable at the pointy end of pro sport. It is relatively easy to set up once you know how, but the process I usually use is as follows:

- Find the person you want to talk to—read their research and understand their context, how they might have used this strategy or training tactic, and how this might be applicable in your environment.

- Find their contact details—Quite often, staff members’ emails are on team websites, researchers’ emails are on their papers, or they have active social media profiles to which you can send a direct message.

- Formulate good-quality questions—take your time and get a good understanding of what you want them to help you with and what you are curious to delve deeper into. You don’t want to waste their time, so ensure you’ve prepared beforehand. Sending a list of questions is advised, as it can help guide the conversation. Show that you are genuinely interested in their work and passionate about knowing more in this area.

From there, you might have a few questions that they can answer over email, often referring you to some of the key work done in that field. If they have piqued your interest, ask for a more in-depth call. Often this will be done on a professional basis, but I continue to be surprised by how some people are happy to chat for free if you ask good enough questions and offer insight from your viewpoint that might be useful to them.

I have too many examples to list, but what starts as a couple of emails can lead you to bespoke, usable insight into their areas of expertise. In the isometric example above, I ended up Zoom calling Paul Comfort, who provided great insight into the data hygiene aspect of tracking isometric training. When I was looking into F-V profiling, JB Morin was able to adapt one of the Excel resources from his website to fit how we captured our speed times.

With some practitioners, it has been mutually beneficial, to the point that I have been able to collaborate with them on projects in the applied setting at the elite level (which is rare for most sport science research). The scientists often want to hear our performance questions because that often helps guide their research, allowing them to go and hunt down the answers!

Make In-Person Visits

If you really want an immersive experience, an in-person visit is a great way to get a deeper understanding. It can take a bit of time to cultivate relationships, but they can be of great value. Seeing a conference presentation or following a few tweets is very different from seeing things up close in their proper context. Not only do you see the coaches in action, but you are afforded an opportunity to ask multiple threads of questions about what you saw on the day.

Seeing a conference presentation or following a few tweets is very different from seeing things up close in their proper context with an in-person visit, says @peteburridge. Share on XAn example I had recently was a visit to see Lassi Laakso at Lugano Ice Hockey Club in Switzerland. It came about from me reading a very good article of his on resisted speed. I reached out with a few questions, and then we had a few discussions over email and Zoom on how we both implemented resisted speed training. Fast forward a year, and I was in my off-season on holiday in Lake Como with my wife. Knowing that it wasn’t too far from there to get to Lugano, I managed to sort out a day to see Lassi coach and talk shop on all things athletic performance.

I went there with a specific interest in resisted speed, but going to an environment outside of rugby allowed me to see a coach looking at things through a different lens with different performance problems. Lassi was doing some things around groin injury prevention that I hadn’t really been exposed to much before within rugby because it is a less prevalent injury than it is in ice hockey. Implementing some of these strategies has helped me put together a much better program for our kickers, who sometimes suffer from overuse-related groin issues. The best bit was that I dragged my wife to Lugano for the CPD visit, but Lugano was such a hidden gem that we stayed for two more days, and it was the highlight of the trip!

Another example is my journey of improving my speed training knowledge. One of the key influencers of my practice is Jonas Dodoo. I first saw him speak at a few conferences and really liked his philosophies around training that he shared on social media.

I realized I needed to get a more in-depth insight into how he went about things, so I paid to go to one of his coach development days. The insights picked up from there were game-changing. We stayed in touch and have collaborated on a few projects since then. He remains a fantastic sounding board whenever I have speed-related problems. All of this came about from an in-person visit where I had the opportunity to ask a million and one questions!

Another great way to do in-person visits is to get someone to come into your environment. This could be paying for a relevant expert to provide in-house learning or an interested practitioner who wants to see and learn from you as much as the other way around! Either way, there is great potential for them to cast an eye on your program and provide good checks and challenges.

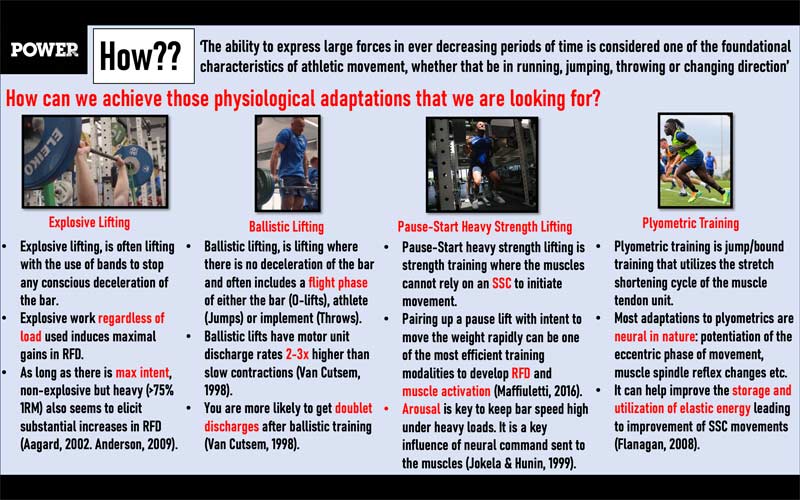

A “philosophy document” or a “performance strategy document” that sums up your approach to developing key physical capacities (speed, power, conditioning, etc.) is not only a great resource to possess on its own, but it can also be used to frame conversations with experts when you invite check and challenge of your processes. Similar to the SOPs (standard operating procedures) the military uses, it acts as a North Star to guide how you do things. You can then use relevant experts to check whether you’re on the right track or if you need to change some of your practices.

Some of the most memorable visits I’ve been a part of have been ones where we have almost deliberately brought someone in who tended to see things differently or even outright disagree with how we did things. Doing this stops you from getting caught in intellectual echo chambers and challenges you to justify why you do things at a deeper level. Sometimes these kinds of visits force you to change your stance on things, and other times they can actually strengthen your beliefs, even with dissenting voices!

In-person visits also allow multiple staff members to experience the CPD, increasing the number of perspectives. Sometimes the most valuable conversations are when the person visiting has left! This is because the most insightful discussions often occur afterward, once you’ve all had time to digest and debrief as a group. This is another strength of the in-house visit; the broader perspective allows you to summarize the key takeaways as a group much more clearly.

I have tried to build the space to allow for a debrief into more visits. I find reducing the intensity of what can sometimes be quite an arduous day—by either going for food or catching up in a more informal setting afterward—adds even more value. I have found that going to Five Guys at the end of the day gets people to reflect a little more honestly, unincumbered by social politeness or not wanting to offend anyone!

One of my fondest memories of this was my first year as an intern S&C coach. I was tasked with being the chaperone for a group of researchers attending one of our games after they presented to us the day before. I went into this thinking I’d get a few hours to ask more questions all by myself and really nail down some key takeaways I could help grow my practice with—unfortunately, the researchers had other ideas. They got blackout drunk so quickly that the only takeaways were cheap pizza and doner kebabs!!

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9049]

Putting It All Together

To sum up, all these strategies rely on you being able to plan and be purposeful with your learning. Much like how we periodize our players’ years, we should do the same with our own. An honest self-evaluation can help you “know what you don’t know” and provide a road map of how to best spend your time for CPD.

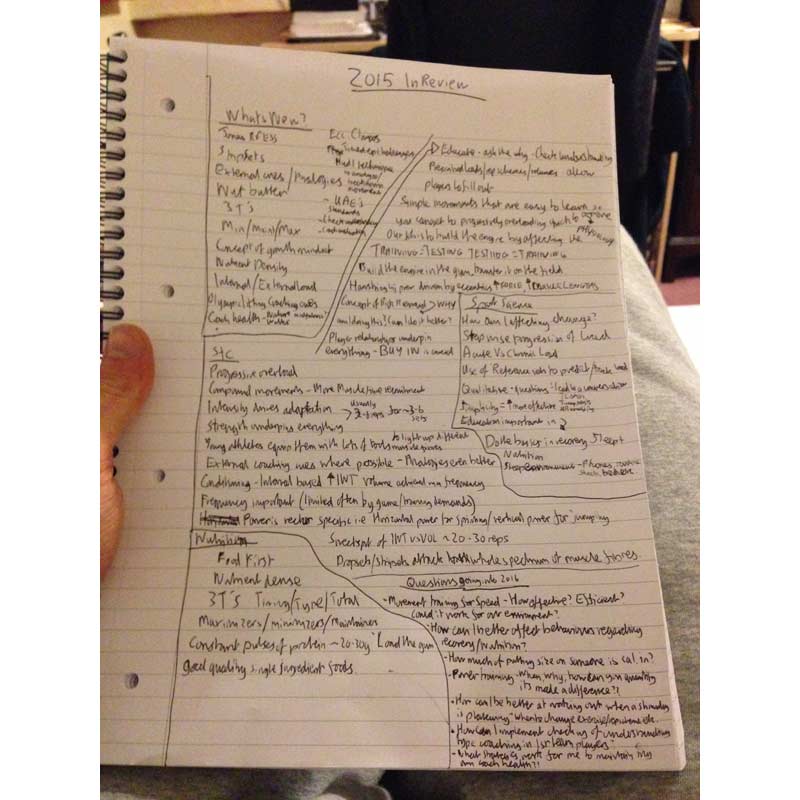

An end-of-year review summarizing the key things you’ve picked up during the year enables you to knot together all the different CPDs you may have done and see how it has changed your practice. Share on XOne of the things I do that has helped me is an end-of-year review summarizing the key things I’ve picked up during the year. This enables you to knit together all the different CPDs you may have done and see how it has truly changed your practice.

Finally, we need to understand that it is less about trying to be the finished product (no one truly is!) and more about the process of being curious to learn more and improve our own practice that counts. We challenge our players to be the best they can be; why shouldn’t we do the same with ourselves?! Having efficient processes for self-improvement is imperative in getting better at getting better.

Hopefully, some of the bits I’ve picked up on my journey can be useful to you on yours too. Failing that, I’m always available for a good burger and a chat about physical performance!!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF