During full range of motion (ROM) bilateral lifting exercises such as squats and deadlifts, a neutral spine posture—defined as an individual’s relaxed standing posture where the stress on the spinal column and muscular effort required to maintain this alignment is minimal26—is commonly included as part of the technical model. However, lumbar spine flexion away from the neutral posture is unavoidable during these exercises.23 During heavy squatting and deadlifting performed through a full ROM, the lumbar spine will typically flex between 50% and 80% of maximum flexion.15 In fact, even when people are coached to maintain a lordotic posture during lifting, flexion relative to a standing posture still occurs.14,22

As spine injuries are common in sports where heavy lifting exercises are performed, avoiding end range flexion could be an important strategy to reduce lifting-related injuries. Share on XAlthough spine flexion during lifting exercises is commonly thought to increase injury risk, submaximal amounts of lumbar flexion may improve lifting performance and possibly lower injury risk through the following mechanisms:

- Decreasing the external moment arm of the barbell relative to the lumbosacral and hip joints, allowing more load to be lifted.18

- Maximizing the hip extensor internal muscles moment arm9 by decreasing the amount of hip joint flexion required to lower the center of mass a given distance28.

- Lengthening the erector spinae muscles, resulting in greater torque generation capability.27

- Potentially facilitating the contribution of the lumbodorsal fascia in providing an internal extensor moment, enhancing metabolic efficiency.14

- Optimizing load sharing by reducing the compressive loading on spinal structures such as the facet joints and the posterior annulus of the disc.2

While it is important to acknowledge the advantages of lifting with moderate amounts of lumbar spine flexion, it should also be recognized that maximally flexing the spine under the extremely high compressive loads seen in the weight room may increase injury risk. As spine injuries are common in sports where heavy lifting exercises are performed (e.g., weightlifting and powerlifting1), avoiding end range flexion could be an important strategy to reduce lifting-related injuries. This article will present evidence for the potential risk associated with lifting in a maximally flexed posture and provide tools that coaches can use to help athletes avoid end range flexion during bilateral lifting exercises.

How Does Maximal Spinal Flexion During Lifting Increase Injury Risk?

During heavy lifting exercises (“heavy” is defined in this article as loads exceeding 10RM), the compressive forces are incredibly high13, surpassing the ultimate strength of the spine reported in cadaver studies29. This disparity can be explained by the osteoligamentous structure’s capacity to remodel following exercise, over time building the spine’s tolerance for the compressive loads experienced during lifting.18 While it is important to appreciate the adaptive capacity of the body, it should not be regarded as infinite. Therefore, lifting technique should complement good programming to help mitigate injury risk and develop robustness.

The primary concern with maximally flexing the trunk during heavy lifting exercises is the tolerance of the spine to compressive forces. When fully flexed, the compressive strength of the passive spine has been shown to decrease by approximately 23%-47% in cadaver models compared to an alignment where the end plates are positioned parallel to each other (which represents a slightly flexed position).19

The primary concern with maximally flexing the trunk during heavy lifting exercises is the tolerance of the spine to compressive forces, says @LouisHowe_SandC. Share on XOne reason for this is that as the posterior ligaments are recruited with full spine flexion, they increase the intradiscal pressures, resulting in a diminished capacity for loading.7 This occurs as the posterior ligaments of the neural arch provide an internal extensor moment to counteract the flexion moment that occurs with lifting. However, the posterior ligaments possess a shorter moment arm relative to the extensor muscles and, consequently, a very high compressive penalty.12

Importantly, this only occurs as we get closer to end range flexion. At 50% and 75% of maximal lumbar spine flexion, ligaments are less strained, resulting in only marginal increases in intradiscal pressures relative to a position of 0% flexion.7 This is one reason why no difference exists in the ultimate compressive strength of the lumbar spine when comparing postures of 0% and 75% of maximal flexion.7

Stress concentrations may also increase on specific spinal structures with a maximally flexed posture. When the lumbar spine is moderately flexed, the superior and inferior endplates are parallel to each other, resulting in an even distribution of load across the disc.5 However, when the spine is maximally flexed, stress concentrations occur at the anterior aspect of the interbody joint, further diminishing the compressive strength of the lumbar spine.

Adams and Hutton4 found end range flexion at a spinal segment increased compression on the anterior annulus by approximately 30%, while stretching the posterior annulus of the intervertebral disc by 50%. This is one reason high compressive forces can cause wedge fractures of the anterior vertebral body when motion segments are fully flexed18, and why full flexion combined with compression can cause posterior disc herniation3.

Another consideration is the anterior shear loading imposed by the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments when recruited with full lumbar spine flexion. Relative to compression, the lumbar spine has a low tolerance threshold for anterior shear forces (approximately 2,000-3,000 N)17 that may be approached with heavy lifting.16 The interspinous and supraspinous ligaments are oriented such that when the lumbar spine is fully flexed, these ligaments pull the superior vertebra forward relative to the vertebra below.21 Consequently, full spine flexion will increase the anterior joint shear forces, increasing the loading on the structures of the neural arch.17

This may explain the findings of Potvin et al.30, where anterior joint shear loads were greater when the lumbar spine was fully flexed compared to a less flexed posture. Lumbar flexion does have advantages when considering shear loading, as it reduces the anterior shear forces imposed by gravity.8 However, there may be a compromise for managing these loads, where joint shear forces can be reduced by allowing moderate flexion to decrease the loading caused by gravity, while avoiding maximal recruitment of the ligaments.

Lastly, when hyperflexion occurs as it can during heavy lifting12, the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments may be the first structures to be damaged6. This risk can be attenuated by avoiding end range flexion at each motion segment by just a few degrees.12

How Can We Coach Athletes to Avoid Full Spine Flexion?

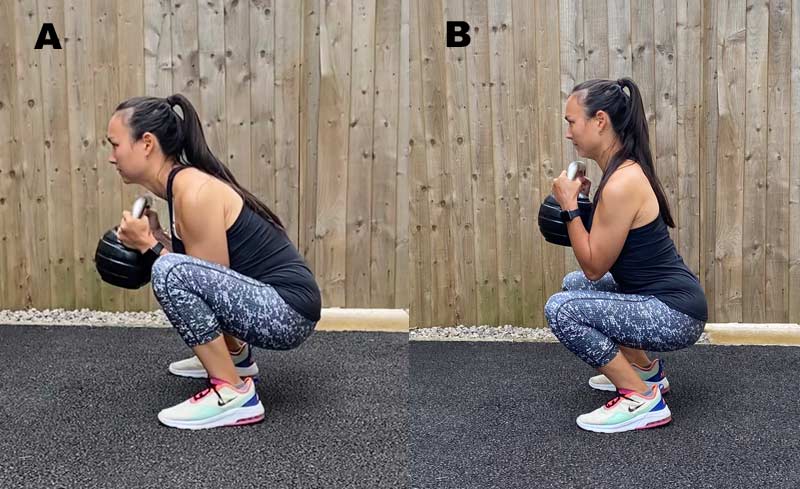

While avoiding maximal spine flexion has the potential to reduce injury risk, moderate flexion (60%-80% of maximum flexion) can improve lifting performance while encouraging optimal load sharing at the spine.2 Consequently, coaches should encourage athletes to maintain a spine alignment that resides within the physiological limits of their ROM during heavy lifting. Generally, allowing the lumbar spine to flex to the point it flattens enables moderate flexion to occur, while avoiding a kyphotic posture of the lumbar spine will help prevent reaching end ROM.2

Coaches should encourage athletes to maintain a spine alignment that resides within the physiological limits of their ROM during heavy lifting, says @LouisHowe_SandC. Share on XBelow is a range of approaches that coaches can incorporate into their practice to help athletes develop coordination strategies that may reduce their injury risk when learning lifting exercises. Importantly, these strategies should be considered in the context of a sensible lifting program that incorporates progressive overload to drive structural adaptations.

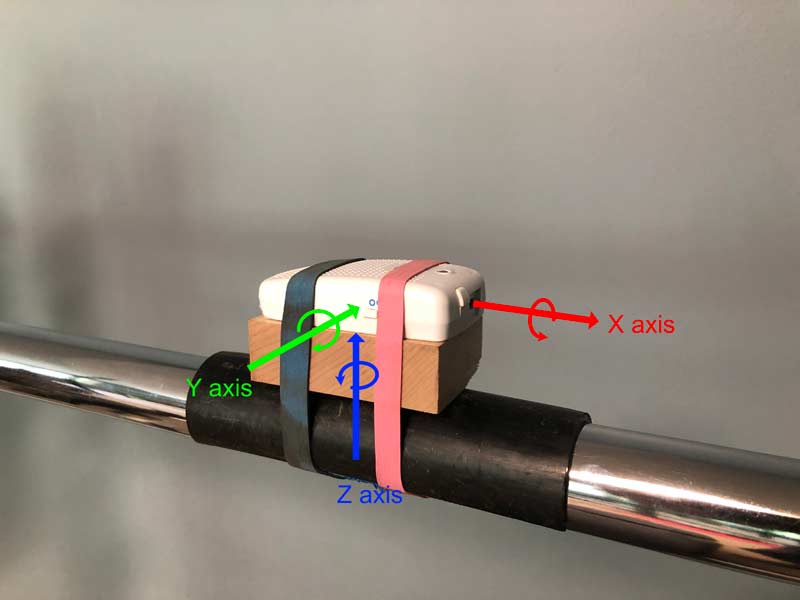

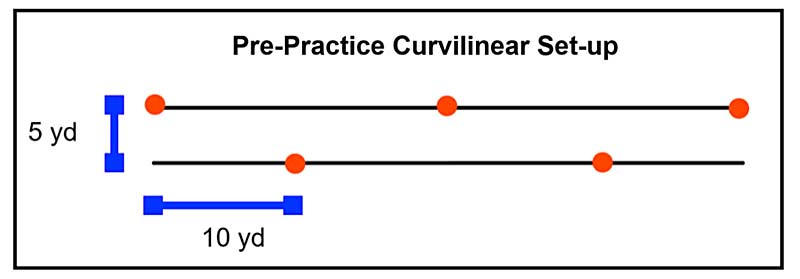

I will also present evidence to support each approach. To accomplish this, I’ve provided images and data taken from a single athlete to demonstrate the effectiveness of each coaching tool. To record lumbar spine posture, peak flexion angles for each movement were calculated using two inertial measurement units (IMUs) positioned at L1 and S2. All values were normalized to the athlete’s standing neutral posture and the maximum flexion angle achieved during the standing flexion test.12

1. Cueing

While obvious, cueing spine posture is well-supported by the literature as a strategy to avoid end range spine flexion. For example, asking athletes to lift “without rounding the lower back” and “maintaining the arch of the spine” has been shown to reduce lumbar spine flexion when lifting a 7.3-kilogram box from the floor.10 While this evidence doesn’t directly relate to heavy deadlifting or squatting, it does provide proof of concept—lumbar spine flexion during lifting can be decreased with appropriate cueing. Depending on the lifting exercise and the athlete’s interpretation, cues that prevent spine motion and/or facilitate lower extremity contribution to lowering the center of mass should be used help each athlete identify movement strategies that avoid end range spine flexion.

2. Develop Awareness for Spine Position

While cueing lumbar spine posture will help most athletes avoid full spine flexion, tactile feedback can also be used to develop the proprioceptive awareness needed to prevent end ROM flexion from occurring during lifting exercises. Example strategies include placing a PVC pipe longitudinally along the spine or applying tape to the spine in order to provide feedback on when the athlete is approaching end ROM flexion during hinging and squatting exercises.

Like cueing, taping the lumbar spine (as shown in figure 2) has been shown to significantly reduce lumbar spine flexion while increasing hip and knee joint flexion during a lifting task.28 Technology like IMUs has also been used to provide real-time feedback to help individuals develop lifting strategies that avoid maximal spine flexion.11 These strategies should be used as a teaching tool, and in most cases, only 1-2 sessions are required to have lasting effects. Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate how tape can be applied to the lumbar spine to help athletes develop an awareness for when their posture approaches end range flexion.

Coaches can apply tape to the lumbar spine to help athletes develop an awareness for when their posture approaches end range flexion, says @LouisHowe_SandC. Share on X

3. Tailor Exercise Selection to the Athlete

Exercise selection will have a large influence on spine posture when lifting for individuals with limited mobility relative to the exercise. For example, a snatch-grip deadlift demands large amounts of hip flexion that, if lacking, will drive compensations at neighboring joint segments. For this exercise, lumbar spine flexion is a common strategy for lowering the hands to the barbell when hip mobility is restricted.

4. Customize ROM

This builds on the previous point and is a similar strategy that you can use to control for spine flexion. There is no rulebook saying that athletes should perform all deadlifts from the floor with 17.7-inch plates. For hypomobile or tall athletes, pulling from blocks or squatting to parallel may be needed to help avoid end range spine flexion.

Coaches should consider an athlete’s capacity to avoid a kyphotic spine posture when deciding on the end ROM of the exercise, says @LouisHowe_SandC. Share on XAs spine flexion gradually increases when lifting,10 reducing the ROM of the lifting exercise will decrease the amount of spine flexion.31 Therefore, coaches should consider an athlete’s capacity to avoid a kyphotic spine posture when deciding on the end ROM of the exercise. Figure 4 demonstrates the effects of lifting ROM on spine posture by comparing lumbar flexion during trap bar deadlifts performed on the ground and from a 4-inch platform.

5. If Needed, Develop an Athlete’s Ankle and Hip Mobility

Having sufficient ankle and hip mobility is crucial for avoiding end range spine flexion when performing full ROM lifting exercises. For example, when ankle dorsiflexion ROM is restricted, it limits the forward displacement of the knees, causing the pelvis to move further back relative to the base of support. To maintain balance, excessive forward lean of the trunk is required, which may result in end range spine flexion.24 Similarly, when hip mobility is limited, early posterior tilt of the pelvis can occur during squatting, increasing spine flexion.25

Movement to Protect the Spine

The spine is incredibly robust and can bear extremely high loads in a range of different postures. During full ROM lifting exercises, lumbar spine flexion is unavoidable and has the potential to improve lifting performance. However, athletes who lift heavy with a maximally flexed lumbar spine posture may have a greater risk of injury, as the compressive strength of the spine is compromised, and the intervertebral discs and posterior ligaments are stressed/strained.

Avoiding end range lumbar flexion can be achieved by developing movement skill through coaching coordination patterns that optimize load sharing at the spine and selecting lifting exercises that account for the athlete’s physical attributes. This can be supplemented, where appropriate, with mobility exercises to help athletes access greater lower-extremity contribution to lowering the center of mass during lifting exercises.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Aasa U, Svartholm I, Andersson F, and Berglund L. “Injuries among weightlifters and powerlifters: a systematic review.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017; 51:211-219.

2. Adams MA and Dolan P. “How to use the spine, pelvis, and legs effectively in lifting.” In: Movement, Stability and Lumbopelvic Pain. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, pp. 167-183, 2007.

3. Adams MA and Hutton WC. “The effect of posture on the strength of the lumbar spine.” Engineering in Medicine. 1981;10:199-202.

4. Adams MA and Hutton WC. “Prolapsed intervertebral disc: a hyperflexion injury.” Spine. 1982;7:184-191.

5. Adams MA and Hutton WC. “The effect of posture on the lumbar spine.” The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, British volume. 1985;67:625-629.

6. Adams MA, Hutton WC, and Stott JR. “The resistance to flexion of the lumbar intervertebral joint.” Spine. 1980;5:245-253.

7. Adams MA, McNally DS, Chinn H, and Dolan P. “The clinical biomechanics award paper 1993 posture and the compressive strength of the lumbar spine.” Clinical Biomechanics. 1994;9:5-14.

8. Arjmand N and Shirazi-Adl A. “Biomechanics of changes in lumbar posture in static lifting.” Spine. 2005;30:2637-2648.

9. Arnold AS, Salinas S, Hakawa DJ, and Delp SL. “Accuracy of muscle moment arms estimated from MRI-based musculoskeletal models of the lower extremity.” Computer Aided Surgery. 2000;5:108-119.

10. Beach TA, Stankovic T, Carnegie DR, Micay R, and Frost DM. “Using verbal instructions to influence lifting mechanics–Does the directive ‘lift with your legs, not your back’ attenuate spinal flexion?.” Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2018;38:1-6.

11. Boocock M, Naude Y, Taylor S, Kilby J, and Mawston G. “Influencing lumbar posture through real-time biofeedback and its effects on the kinematics and kinetics of a repetitive lifting task.” Gait & Posture. 2019;73:93-100.

12. Cholewicki J and McGill SM. “Lumbar posterior ligament involvement during extremely heavy lifts estimated from fluoroscopic measurements.” Journal of Biomechanics. 1992;25:17-28.

13. Cholewicki J, McGill SM, and Norman RW. “Lumbar spine loads during the lifting of extremely heavy weights.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1991;23:1179-1186.

14. Dolan P, Mannion AF, and Adams MA. “Passive tissues help the back muscles to generate extensor moments during lifting.” Journal of Biomechanics. 1994;27:1077-1085.

15. Edington C. “Lumbar spine kinematics and kinetics during heavy barbell squat and deadlift variations” (Doctoral dissertation), University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon; 2017.

16. Edington C, Greening C, Kmet N, et al. “The effect of set up position on EMG amplitude, lumbar spine kinetics, and total force output during maximal isometric conventional-stance deadlifts.” Sports. 2018;6:90.

17. Gallagher S and Marras WS. “Tolerance of the lumbar spine to shear: a review and recommended exposure limits.” Clinical Biomechanics. 2012;27:973-978.

18. Granhed H, Jonson R, and Hansson T. “The loads on the lumbar spine during extreme weight lifting.” Spine. 1987;12:146-149.

19. Gunning JL, Callaghan JP, and McGill SM. “Spinal posture and prior loading history modulate compressive strength and type of failure in the spine: a biomechanical study using a porcine cervical spine model.” Clinical Biomechanics. 2001;16:471-480.

20. Hales ME. “Improving the deadlift: Understanding biomechanical constraints and physiological adaptations to resistance exercise.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2010;32:44-51.

21. Heylings DJ. “Supraspinous and interspinous ligaments of the human lumbar spine.” Journal of Anatomy. 1978;125:127-131.

22. Holder L. “The effect of lumbar posture and pelvis fixation on back extensor torque and paravertebral muscle activation” (Doctoral dissertation), Auckland University of Technology; 2013.

23. Howe L and Lehman G. “Getting out of neutral: the risks and rewards of lumbar spine flexion during lifting exercises.” Strength and Conditioning. 2021;60:19-31.

24. List R, Gülay T, Stoop M, and Lorenzetti S. “Kinematics of the trunk and the lower extremities during restricted and unrestricted squats.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2013;27:1529-1538.

25. Mata AJ, Hayashi H, Moreno PA, Dudley RI, and Sorenson EA. “Hip flexion angles during supine range of motion and bodyweight squats.” International Journal of Exercise Science. 2021;14:912-918.

26. Panjabi MM. “The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and instability hypothesis.” The Journal of Spinal Disorders. 1992;5:390-397.

27. Parnianpour M, Li F, Nordin M, and Kahanovitz N. “A database of isoinertial trunk strength tests against three resistance levels in sagittal, frontal, and transverse planes in normal male subjects.” Spine. 1989;14:409-411.

28. Pinto BL, Beaudette SM, and Brown SH. “Tactile cues can change movement: An example using tape to redistribute flexion from the lumbar spine to the hips and knees during lifting.” Human Movement Science. 2018;60:32-39.

29. Porter RW, Adams MA, and Hutton WC. “Physical activity and the strength of the lumbar spine.” Spine. 1989;14:201-203.

30. Potvin JR, McGill SM, and Norman RW. “Trunk muscle and lumbar ligament contributions to dynamic lifts with varying degrees of trunk flexion.” Spine. 1991;16:1099-1107.

31. Yanagisawa O, Oshikawa T, Adachi G, Matsunaga N, and Kaneoka K. “Acute effects of varying squat depths on lumbar intervertebral disks during high‐load barbell back squat exercise.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2021;31:350-357.