Prepare for the worst and hope for the best. The concept of “worst-case scenario” is the brainchild of some of the most ingenious military experts, and with this idea, Confucius, Lao Tzu, Marcus Aurelius, and many other historical figures armed their troops. The “worst-case scenario” is one of the most commonly used alternative scenarios for performance coaches in rugby.

As a general rule, a worst-case scenario is decided upon by agreeing that a scenario is serious enough to assume the responsibility of representing the worst. However, it is important to recognize that no “worst-case scenario” is truly without the potential for further unpleasant surprises. In other words, a “worst-case scenario” is never guaranteed to be the “worst case,” because situations can arise that no planner can reasonably predict, and a given “worst-case scenario” may only consider the contingencies that may arise in relation to a particular disaster.

For instance, the “worst case” imagined by a seismologist could be a particularly severe earthquake, and the “worst case” imagined by a meteorologist could be a horrendous hurricane. Neither one of them is likely to design a scenario in which a particularly severe storm occurs at the same time as a particularly severe earthquake.

For most people, the worst case is the one that would result in their own death, and the way we define the “worst-case scenario” in sport is evolving. When I was 10 years old, during my endless weekend rugby tournaments, the “worst case” was the absence of sandwiches and steak fries at the refreshment area (a must-have dish for a player of my caliber). Today, as a sport scientist or high-performance practitioner in professional rugby, armed to the teeth with super-powerful technologies—and, more particularly, with GPS—we use data to define the contours of a “worst-case scenario.”

Applying GPS Data to Calculate Worst-Case Scenarios and Design Training

For a long time, GPS analysis of matches in rugby or football only reported average movement data (distance, m/min, high speed distance, etc.) for both halves and then the entire match. While such data is beneficial in profiling the overall requirements of a game, using averages is likely to underestimate peak demand (and therefore worst-case scenarios encountered in the match).

The change in mindset regarding GPS analysis revolves around the assumption that in order to optimally prepare athletes for the demands of competition, it is essential that they are trained to face the most intense periods of the game and not just the average demands. The ability to design training exercises that simultaneously develop physical qualities that meet or exceed the movement requirements of the match would represent an effective and stimulating training environment.

Several methods of calculating the “worst-case scenario” exist. Using smaller fixed periods (10 minutes, for example) provides additional insight into the most demanding passages of play. However, this method was found to be inferior compared to a moving average method for determining high-speed distance (HSD) values during football matches.

In a recent study, using five-minute periods of fixed time (e.g., 0-5 minutes, 5-10 minutes, etc.) and moving averages of the same duration in elite football matches, an overestimation of 31% of HSD distance in fixed time analysis was reported. Likewise, in rugby sevens, a two-minute moving average was used to assess the most demanding phases of the game in terms of relative distance traveled and metabolic power. Others have used relative distance, average number of accelerations/decelerations, and average metabolic power as measures to describe maximum running intensities (for moving average periods of 1 to 10 minutes) during international rugby union matches.

A simple method is:

- Select a period (one minute, two minutes, five minutes, etc.) and analyze the chosen GPS data.

- Focus on the moving average of that data, period after period.

- Apply this method of analysis to a random number of matches.

- Focus on one player at a time or on a group of positions (front rowers, for instance).

- Notice and write down for which period the values of the analyzed data are the highest for each player or group of positions.

Voila!—you now have a “worst-case scenario.” In fact, the above description reflects a simplistic version of the calculation of a “worst case” in rugby (each club has its own recipe, with more or fewer ingredients).

But the real problem is not there—not in the details of a calculation and not in the intricacies of statistical thinking.

The problem is in the very conception of the “worst-case scenario.” A scenario is, by definition, imagined. It represents anticipation. A scenario has alternatives; it is malleable and agile. Identifying the most intense game passages and using this data to guide training content to ensure that players are exposed to the maximum intensities of their sport has nothing in common with the idea of scenario. It is a work of analysis, requiring a certain scientific rigor, far from the fantasy and the cunning required to establish a scenario. Identifying and knowing how to wisely use data sets related to the most intense parts of a match is a prerequisite for programming a physical preparation plan, as is knowing the rules of the game, the calendar of competitions, etc. In short, this is to do your homework and know thy terrain.

Building a worst-case scenario involves looking for uncomfortable situations, pressing where it hurts, making the unthinkable painfully palpable. Share on XBuilding a worst-case scenario is quite another thing. It is looking for uncomfortable situations, pressing where it hurts, making the unthinkable painfully palpable. Go flirting with something new, almost inconceivable—this is not an attempt to copy/paste a pre-defined data set to a game situation.

Thinking that a worst-case scenario is the equivalent of a reproduction of data associated with passages of game action identified as “the most intense” should be called into question.

First, there are so many parameters to take into account when we want to define and measure what is the most extreme physiological and psychological demand placed on an athlete in the context of their sport. How can coaches be absolutely certain that what we consider to be the most intense parts of the game are really the most intense parts of the game? Frequently, the yardage per minute is used to define a “worst case.” The latter is, however, a simple density marker that some people take for an intensity marker.

A Ferrari and a Renault Clio can both be flashed at 150 km/hour. This does not mean that they are of equal power, nor that they consume the same amount of fuel. Observing that a player travels at 150 meters/minute over a period of two minutes does not provide any information on the energetic, mechanical, and psychological cost of those two minutes for the player in question.

Another favorite marker—high-speed distance—comes up against a problem of dependence on the maximum speed of the individual. Recording a value of 201 meters above 5 m/s (20 km/h) for player A over a period of two minutes does not provide any information on the intensity of this passage of play, except if related to the percentage of maximum speed that 5 m/s represents for that player, and if we consider the real speed variation during this period.

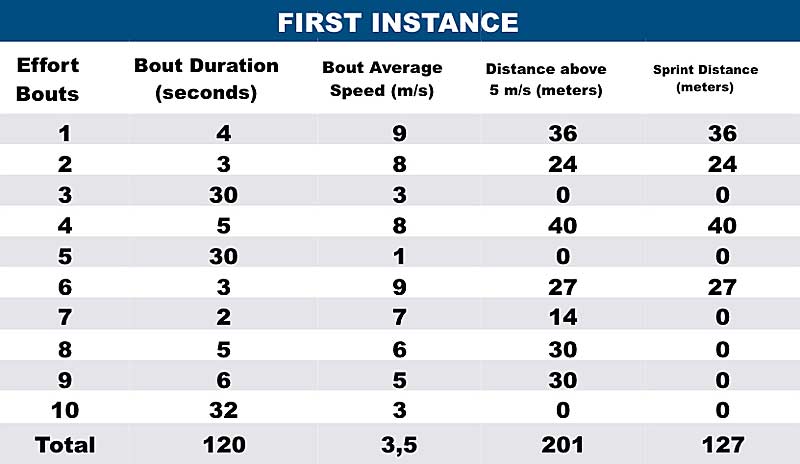

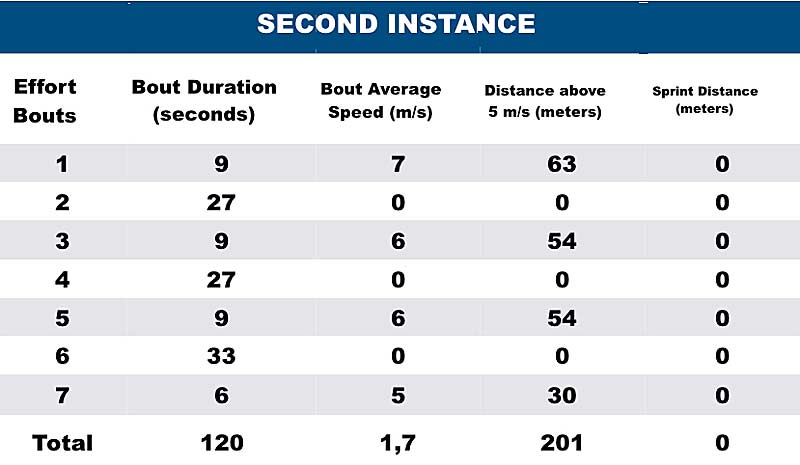

Let’s consider the following situation: Simon is one of your players. His max speed is estimated at just above 9 m/s. Twice this year you recorded passages of plays where he realized a high of 201 meters of high-speed running distance (above 5 m/s) over a two-minute period (as part of your rolling average analysis). Now, if you were to look into those two-minute periods with a microscope and look at each change of speed as a new bout, this is what you may find:

In the first instance, the 201 meters above 5 m/s over a period of two minutes comes with nearly 20% of the time spent at over 90% of maximum speed, as well as a sprint distance of 127 meters. The recorded activity would therefore correspond to three substantial sprints interspersed with periods of lower activity.

In the second instance, the 201 meters above 5 m/s over a period of two minutes are characterized by 0% of the time spent above 90% of the maximum speed and no sprinting, but almost 25% time spent at 70% of maximum speed and 75% of time spent at a standstill. The above activity would be categorized as intermittent.

No strength and conditioning coaches would argue that these two activities have the same physiological and psychological impact.

Dynamic Feedback, Nonlinear Amplification, and Turbulence

Defining the most intense game passages requires an individualized approach. For each individual athlete, a number of factors should be combined to determine the characteristics of an intense passage of play:

- Specific position requirements.

- Innate preferences and acquired skill.

- Archetype and psychological profile.

If there are 15 players on the field (in your team) and as many different profiles, it is possible—but difficult—to define the spectrum of the most intense passages of play. On the other hand, it is almost impossible for your 15 players to experience their individual version of an intense passage of play simultaneously over a period of one, two, or even five minutes. Using this data to inform a suitable training program is consistent, but using it in an attempt to construct a common “worst-case scenario” is illusory.

Confusing the identification of the most intense passage of plays of a game and the “worst-case scenario” in rugby or other team sports testifies to an altered conception of the laws governing this type of activity.

A rugby match is a confrontation of two complex systems (two teams), characterized by the successive alternation of order and disorder, stability and instability, uniformity and variety. A rugby match is nonlinear, unpredictable. In chaos, prediction is not possible because nothing obeys a set of predefined rules. Can we define what will be the worst part of an event that we cannot predict with precision?

In chaos, prediction is not possible because nothing obeys a set of predefined rules. Can we define what will be the worst part of an event that we cannot predict with precision? Share on XLike the radar flashing for just an instant on the long road traveled by the driver, isolating a row of data over a predefined period gives a frozen image. A decontextualized and cold understanding. Extrapolating a concept of “worst-case scenario” from a data extract makes no sense. It’s all about the dynamic aspect, the sequencing, the accumulation. The physiological and psychological states of the player at the instant of the passage of play identified as “worst case” are only transient, and only exist because they are caught in a chain of events and reactions.

A rugby match is governed by certain principles and building a “worst-case scenario” must obey these principles.

- Dynamic feedback. From the kick-off, every action, every pass, every tackle, and every point scored affects the next action as well as the behavior of teams and individual players. When it is isolated, a relatively simple action—such as a penalty in front of the posts—is technically the same in appearance, whether it takes place at the start or at the end of the match. But, depending on the score and the time remaining, it is perceived as having a different importance. The goal scorer’s heart rate and players’ cortisol levels will be different.

- Let’s say, then, the “worst-case scenario” for this team is estimated using the number of accelerations over a two-minute period as a marker. If these two intense minutes are produced during the last two minutes of a game, where the gap on the scoreboard is one point, or somewhere in the first quarter of an hour of the game, is the real physiological and psychological cost the same? For a certain amount of measured locomotor activity, the associated physiological demand is not a fixed reality. The context in which this activity is carried out greatly impacts its “cost” for the system.

- Nonlinear amplification. Situated in Australia, the team I worked for lost in the NRL semifinals when they were hot favorites. A few minutes after the kick-off, a player from my team, one of the best wingers in the competition, sent a pass straight into the arms of an opponent 20 meters from our in-goal. The latter spun laughing between the posts and opened the scoring.

- The negative psychological impact on our team and the galvanizing effect on the opposing team were considerable. Six points is an easily surmountable deficit in rugby league, but falling from favorite to amateur status in the space of a second—and because of an unimaginable blunder—was fatal. Regardless of the intensity of the races or our domination in the collisions, the loss of confidence from the start of the match got the better of physical capacity and technical quality when it came to defeating a “worst-case scenario.”

- Turbulence. In a game, as in life, there is an interconnection between different events that act on each other. Two events, hypothetically impacted by the same conditions and occurring at the same time, may have a completely different course and end due to the turbulence of another. In a rugby match, if a team loses its best player through injury and concedes a try in the process, it can become a major obstacle. Taken in isolation, each of these events is surmountable—the whole team is prepared to face this type of adversity. In contrast, the cumulative effect makes these games’ moments much more critical.

- The same is true when studying GPS data used to define a “worst-case scenario.” It’s simple to prepare players to sustain a given yardage per minute or number of accelerations for a preset amount of time. But what if we add collisions to that? And if any rugby player is able to move at a high pace while suffering collisions, what if you add harsh weather conditions? A succession of questionable arbitration decisions? A period outnumbered? Exposing players to a particular difficulty such as playing at a certain yardage per minute, or wetting the balloons to make them slippery, does not guarantee an improvement in performance when faced with an accumulation of difficulties.

A combination of events also has an impact on the energy level. When identifying an “intense passage of plays,” it is necessary to place it in a dynamic context. Players never participate in these most intense passages of plays free of any energetic and psychological baggage—the physiological and psychological states of the player at the time they experience this most intense phase of plays is a determining factor in their ability to produce the expected performance and the impact of this physical demand on their attitude during the minutes that will follow.

High-Intensity Game Moments ≠ The Worst Case

When discussing worst-case scenarios for the purposes of training, many actually describe “the most intense part of the game—or passage of plays.” The difference, however, is notable. The latter is a capture, a temperature measurement, a clue. It is quantifiable, reproducible. It is based on a common language: data.

Once the most intense passage of plays has been identified, the data values characterizing them can be used for training programming. Not to be foolishly reproduced identically at all costs, but to inform training loads and delimit what are the requirements for each position to target during specific physical work. The true worst-case scenario, on the other hand, is an emotion, a chaotic spectacle, a surprise. It is constantly varied, subjective. It is based on individual feeling. A “worst-case scenario” is a micro-dose of concentrated adrenaline given to a team when it needs to be tightened. When it needs to evolve.

Confusing these two tools gives rise to popular nonsense today. Obsessed with this little bit of a match that they wrongly call “worst-case scenario,” a fashionable performance coach can produce—without realizing it—aberrant training strategies.

For example, armed with data they believe defines a worst-case scenario, they impose game sequences of a predetermined duration. They assure everyone who listens that it is essential to work on the “worst-case scenario” with the ball, as in a match! But the outcome of the period of plays they impose does not matter to them. That the ball is on the ground, that the technical and tactical aspects of the game are suddenly seen as secondary, this does not disturb them. In order to stage their “worst-case scenario,” they also define an effort: a recovery ratio that they reproduce many times to achieve the desired amount of “worst-case scenario.” However, they are well aware that the sport for which they prepare their players in no way obeys a constant effort:rest ratio.

In any team sport, even to some extent American football, periods of continuous plays alternate with breaks of unpredictable, constantly changing durations entirely determined by the evolving context of the game. By standardizing an effort:recovery ratio, the strength and conditioning coach deprives the worst-case scenario of an essential energetic aspect: metabolic flexibility.

More than ever in control of their ship, the physical trainer who confuses GPS data and an actual worst-case scenario is ready to make many sacrifices to reproduce their expectations. Having become biased, they allow the type of data recorded to influence the way in which the game is played in the context of their “worst-case scenario.” So, while they’re looking for high meters per minute values, they limit the confrontation that hinders the multiplication of player movements.

If, on the other hand, it is the number of collisions that interests them, they offer a reduced field of play. In the name of their worst-case scenario, they defy the rules of the sport and are prepared to compromise the only constant guarantees beyond which the match is never played (proportion of playing field, number of players). They come to feel a certain disdain for the identity of their team, for the strategy advocated by the head coach, and even for the strengths on which the success of the collective rests.

For a rugby team, if the strength and conditioning coach aspires to build up high-intensity distance in their worst-case scenario exercise, they will encourage airy play, space-seeking, support runs. They will take turns throwing balloons into the deep field if necessary. And yet, many times this type of work will be present within teams that, at the weekend, will pride themselves on being present in the physical challenge and will focus their game strategy around their forwards and conquest, far from all the crazy races and open space plays that populated the so-called “worst-case scenario” of midweek training.

Basic Elements of a True Worst-Case Scenario

Creating a worst-case scenario is possible. It is available to any strength and conditioning professional who knows the activity for which they are preparing players. There are only three simple rules that frame the principle of worst-case scenario:

- It must contain an element of surprise. A situation experienced many times before can no longer be the worst possible situation—when the player knows every detail of the scenario that awaits them, they adapt. They use strategy. They repeat the movements and becomes more efficient. With each new exposure to this situation, the difficulty is reduced. It becomes more and more common and consequently less and less extreme.

- To face a worst-case scenario is to respond to an extreme and new situation, which requires that we find exceptional physical and mental resources and mobilize them at the appropriate moment. When this scenario is routine, when it loses its unpredictability, it no longer allows one to search deep within oneself for as-yet-unexplored capacities.

- It only exists within a defined framework. It must respect a certain level of specificity and be contained within the range of possibilities of the activity practiced. For a firefighter, a “worst case” cannot be a rescue in the depths of the ocean. This is just not their area of practice. And although such an experience can be of great benefit to their psychological resilience, in the course of their career they will never face an adversity requiring the mobilization of physical and mental resources similar to those of a diver-rescuer in deep water.

- In sports, the fundamental rules and conditions for the practice of the game itself must be observed. For rugby players, for example, asking them to run a marathon does not confront them with the “worst” of their activity. Distorting the activity practiced in order to make it artificially more demanding in terms of the expression of a particular physical quality does not serve the objective of a “worst-case scenario.”

Producing an unusual physiological and psychological demand through a modification or omission of a fundamental rule certainly has its place in physical preparation, but it does not constitute a “worst-case scenario.” Making a “touch” instead of a tackle in rugby practice—thereby limiting collisions—is a simple and effective way to generate increased running demand. While perfect for aerobic development, if your players start touching opponents instead of tackling them on match day, you won’t be so proud.

For a 100m runner, a “worst-case scenario” is not a 200m or a 400m: it’s a 100m against the wind, with a shoe that breaks. For a rugby player, a “worst-case scenario” is not an Australian football game nor touch rugby. It’s a rugby match with a hostile crowd, a numerical inferiority, a technically catastrophic start to the match.

- The worst-case scenario must respect the principles mentioned earlier that are verifiable in all team sports and are the guarantors of suspense: the dynamics of interactions between teams and the physical and psychological difficulty of a match. In a situation of setting up a worst-case scenario, the principle of dynamic feedback requires special attention. Players don’t like running in vain, let alone when it’s supposedly “integrated physical preparation.” As competitors, they are used to influencing the course of action through their initiative and decision-making.

- A “worst-case scenario” in rugby where the strength and conditioning coach is concerned solely with the amount of movement, and swings balls in all directions as soon as the game is slowed down, goes against this principle. In this example, the player has no way of responding to the situation using dynamic feedback. If they decide to press defensively and dominates their opponent in the collision, play may stop, and a ball may be given to the opposing team in the deep field. If they miss a tackle and the opponent spins alone toward the try line, play may stop, and they may be offered a ball. As the current scenario is in no way influenced by the individual and collective choices of the players, it will not be associated with the match experience of the latter.

A judicious worst-case scenario addresses the principle of nonlinear amplification. It presses where it hurts. A simple example? In the weekly training opposition, take one or two clear starters and get them out of the match group. Give their bibs to two players who have rarely been to first team games.

A judicious worst-case scenario addresses the principle of nonlinear amplification. It presses where it hurts. Share on XDo not tell any player your reasons. Watch the panic in the looks players silently throw at each other. Communication becomes difficult, unusual mistakes multiply. Doubt appears in their minds. Change some players’ positions, move training to a hostile and unfamiliar place, change the schedule and call the team very early in the morning or late at night…there are many options to test the ability to adapt to the unexpected and create an exacerbated experience of the principle of nonlinear amplification.

Turbulence (A Slight Return)

What about the principle of turbulence? Don’t let it escape your “worst-case scenario” situation! Go get that straw that might break the camel’s back: an opposition to training, where the physical trainer becomes a more-than-biased referee, awarding penalty after penalty to one team, and litigiously condemning the other. If, in addition, the victim of this manipulation is outnumbered, or if players are forced to wear two jerseys one on top of the other when their opponents are lounging in the comfort of their training t-shirts, then the accumulation of adversity will reveal the character of this group of players.

The vast majority of strength and conditioning coaches understand the relationship among training load, fatigue, and coping. However, under the influence of pseudo-scientific papers and a fear of appearing incompetent in the eyes of their colleagues, many persist in accommodating several sequences of “the most intense passage of plays” (or “worst-case scenarios”) in a session, always the same and week after week. The same conscientious professionals who study in great detail how to solicit the lower limbs in bodybuilding without creating significant residual fatigue punish their troops with long minutes of so-called “worst-case scenario” on a weekly basis.

Each team is at its own stage of development, and physical preparation needs vary. Working out at near maximum intensity in small doses during a typical week of training is usually a strategy that pays off in the long run. Using a “worst-case scenario” here and there during a season is the key to maintaining a competitive and resilient team. However, in sports where games take place every weekend, once the competition phase has started, the relevance of a weekly physical and psychological stress such as the one imposed by a “most intense passage of plays sequence” or “worst case-scenario” is questionable.

Using a ‘worst-case scenario’ here and there during a season is key to maintaining a competitive and resilient team. Share on XThere is no such thing as an easy match, and each week the previous meeting leaves traces that are still noticeable when the next opponents knock at the door. Players, like any other individuals, do not have endless resources. At any time in a week of classic preparation, technical, strategic, and physical needs compete for the players’ physiological, emotional, and psychological resources. Deciding to tap into their reserves by exposing them to the physically exhausting “worst-case scenario” has an irrevocable impact on the ability to assimilate the strategic directives given by coaches and improve technical skills. Spending time and energy each week to accustom players to the physical demands of “the most intense parts of the game” is a high-risk and low-return sort of investment.

The (Best-Case) Alternative

Week after week, the “most intense passage of plays” or “worst-case scenario” work sacrifices an opportunity to devote more resources to technical and strategic development. To think, for a single second, that inferiority or superiority in the area of physical ability when exposed to a stint of ultra-intense plays is synonymous with defeat or victory is indicative of a misunderstanding of cause-effect relationships. Recent studies in NRL show that the best teams have a lower physical work output than the worst teams…Yet, when only the GPS data is taken into account, the teams with the highest numbers are also the lowest ranked.

By putting things in context, it becomes evident that a huge energy expenditure is often the mark of teams that lack control. High-intensity distance is easy to accumulate when chasing opponents who seem intractable. The meters per minute skyrocket when spending your time defending.

What strikes me today is that no one seems comparably interested in the idea of best-case scenario. Yet anyone who did their homework in cognitive theory knows that the acquisition and development of motor skills is compromised the moment fatigue sets in. If you spend the majority of your time training your players at very high intensity, you will inexorably compromise their motor control and the quality of their technical skills.

After running a 400m as if it was an Olympic final, who will score the most penalties in football—an experienced player or a novice? Easy. Now, if the experienced player exhausts themselves at top speed over 400 meters right before their attempts (and does this daily), while the novice perfects their ball hitting with freshness, the gap will quickly narrow.

Contrary to what seems to be the dominant theory—that getting used to extreme conditions is the key to being successful when these conditions arise—I am among those who believe that it’s the level of mastery of the technical gesture and motor skill that determines performance when conditions are extreme. If your mastery of the pass in rugby is excellent, for example, increased variability of your motor pattern induced by fatigue resulting from a “most intense passage of plays” will not diminish the quality of your gesture so much as to put your team at risk.

I am among those who believe that it’s the level of mastery of the technical gesture and motor skill that determines performance when conditions are extreme. Share on XOn the other hand, if you do not fully master this technical gesture, if your attempts are generally variable, then the effect of fatigue will be catastrophic on the achievement of this motor skill. And, as mentioned, we do not develop perfect control of an action if we practice it mostly in a state of fatigue, with disturbed motor control and memory thwarted by too pronounced of a sympathetic activation.

The “worst-case scenario” and the “most intense passage of plays” are the domain of the weekend: the match itself. The unpredictable; the inevitable. Players will respond to it in empirical, surprising, sometimes exciting, and sometimes disappointing ways, guided by experience and instinct. The truth of the matter is that you only learn from what you have suffered. Sometimes it’s true, you have to bring these approaches into training to get over it, but it’s still an extra.

The “best-case scenario”—the “normal passage of plays”—is the permanent domain of training. Practice with awareness, do things well, adapt, and don’t react. Weightlifters have been saying it for a long time: “Slow is smooth and smooth is fast.” In other words, practicing perfection allows for self-realization, and self-realization generates intensity.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Whitehead, S., Till, K., Weaving, D., and Jones, B. “The Use of Microtechnology to Quantify the Peak Match Demands of the Football Codes: A Systematic Review.” Sports Medicine. 2018;48:2549-2575.

Woods, C.T., Sinclair, W., and Robertson, S. “Explaining match outcome and ladder position in the National Rugby League using team performance indicators.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2017;20(12):1107-1111.

Game Changer. F. Connolly, 2017.