Kris Robertson is an S&C coach with Rugby Canada. He leads the Senior Women’s National XV’s and the Women’s Rugby Canada Academy training program from a physical development standpoint. He believes in supporting athletes through structured and sound programming, application, and meaningful relationships.

Freelap USA: Periodization is often seen as dead in some circles, but some coaches feel it’s doing just fine. How do you see planning now with athletic development when the desire for competition is so prevalent? What should coaches do now?

Kris Robertson: The concept of periodization is only seen as dead in some circles because the definition, in my opinion, has changed from the seminal texts of Matveyev. I find when talking to coaches that the definitions of periodization and planning seem to get intertwined. The more experience you get as a coach, the more you realize how much your initial plan gets altered throughout the training process. From the time we write it down on our nice Excel sheet to the time we actually administer the training, so much has changed, and this sequence of events can lead coaches to say periodization doesn’t work, or it’s dead.

When you dig into the seminal texts, the definition of periodization is “the logical and systematic sequencing of training factors in an integrative fashion in order to optimize specific training outcomes at pre-determined time points.”1 Now planning, on the other hand, is the organization and arrangement of training structures into phases in order to achieve targeted goals.1 Periodization is simply the 10,000-foot view of the entire training structure, and everyone does this in some form or fashion.

With that being said, I don’t feel it can be “dead,” as some may allude to. When you work with a team, athlete, or client, the first thing you do is build out a map. Whether it is all pretty on Excel or in your head, you have an idea of the sequence of training phases you want to do. That is periodization in a nutshell.

With this understanding, coaches should just work backward from the competitive event. You will map out individual sports such as track and field or swimming, which have one or two peak events, accordingly, while team sports—where you need to string together multiple weeks that are all important—require different periodization strategies. With my rugby academy athletes, we go through periods where they have multiple competitions, and I was inspired by Vince Kelly. He and his colleague wrote a great paper on how to manage loads during the season based on a few variables: quality of opposition, number of days between games, and match location.2 This is something I use with a couple of different variables that fit my environment.

Periodization is simply the global view of your training program, says @CoachKStrength. Share on XPeriodization is simply the global view of your training program. There a few periods of time where you know the training adaptations you are looking to elicit, and these periods are about the only aspect of your plan that are certain. Having this understanding becomes important for working with your athletes to achieve peak performance when it counts most: game day!

Freelap USA: You work in both team and private sector environments, so you experience the challenge of inheriting both well and poorly coached athletes. How do you see your role as a private coach when helping athletes now?

Kris Robertson: I was always taught to “control the controllable.” Have I worked with an athlete who wasn’t coached to an adequate standard? Yes. But if we, as coaches, let that stop us, the state of strength and conditioning would be the Wild West. With that being said, I feel the best thing you can do is educate your athletes. Education is something I pride myself on, and I do my best to make sure my athletes leave each session with one or two new things learned.

I like to describe my teaching via durable versus transient qualities. Durable qualities are behavior-based—these are qualities that will last a lifetime and transfer outside of the DTE. Durable qualities are simple things such as: Can your athlete read a program? Can your athlete detect when something is off with their technique? Can your athlete correct other athletes on their technique?

These become very important because your athletes won’t always be with you. As a coach, your goal should be that your athletes are coached up to the point that they don’t need you. Whenever I start working with new athletes, I always give a speech about how my job is to make sure they don’t need me.

Transient qualities are the qualities that come and go—these qualities are the sweet stuff everyone goes crazy over. Transient qualities are usually based around performance goals such as speed and power outputs. As coaches, we know these qualities aren’t always going to be their best all year round. Once you teach the durable qualities, athletes will then be able to understand that they will go through periods where performance will be dampened.

All in all, education is the key to growing our profession. I get it—in the private space, chasing the transient qualities is how you keep your lights on—but you know how you can walk and chew gum at the same time? In my experience, the good athletes will do anything to get better. Sometimes slowing things down and coaching them up will springboard them to a whole new level.

Think of it in weightlifting terms: We have all seen the strong athlete with poor technique. When we see that, we drop weight and coach them up, and then they go on to break their PR’s. That is essentially how athletes want to be taught. I slow them down and educate them on their weak links. Once they are educated, they then go on to reach new heights.

Freelap USA: Programming or writing workouts is a real responsibility. Describe your process and how it’s evolved over the years. Do you plan more than you did in the past or keep things more agile?

Kris Robertson: When I first got into my role at Rugby Canada, I made it a goal of mine to figure out how to write a program. In the past, I went off what I did when I was an athlete. While it worked for me in the past, I knew there were other ways, so I began exploring. The first book I came across was The Coach’s Strength Training Playbook by Joe Kenn. I have so much respect for him and this book, as it really helped me grow as a coach. Although I do not use his system the way he does it, I have remixed his ideas to the point I have created my own system. Thank you, Joe.

After three years, I now have three total body templates I use for my athletes and two upper/lower split templates. These templates all serve me well, and I can adapt them to almost any environment or situation. My process starts out with a simple needs analysis of the athlete and then the sport. What is the athlete’s training age? What are the biomotor abilities of the sport? What is the biodynamics of the sport, and what bioenergetic abilities are needed for the sport?

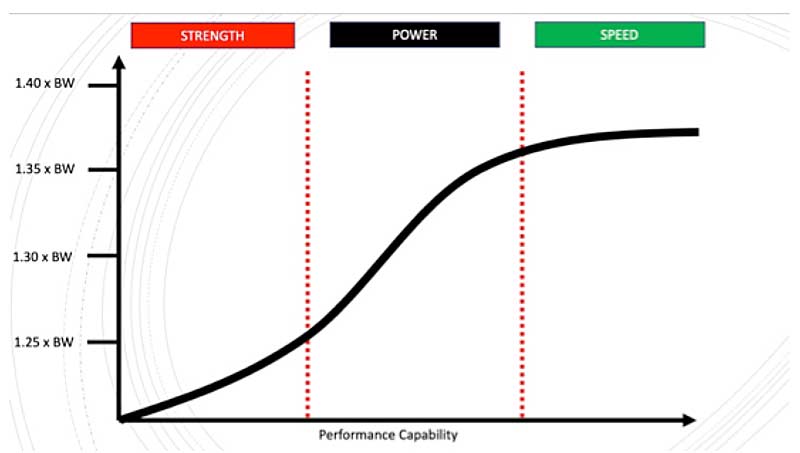

Speed is the underlying biomotor ability I am trying to improve, as this is a major KPI for rugby 7’s. With speed in mind, I put athletes into three buckets: strength, power, or speed (Figure 1). Once athletes are put into buckets, programming becomes easy because I know the prescription for the athlete.

Going back to what I said earlier with regard to periodization and planning, I develop a really simple YTP to give me some direction, and then I plan block to block based on what I see from my athletes. I am a firm believer that exercise selection does not matter in the general preparation phase. I like to chase the adaptations, and the results always follow. As we get more specific, I have identified a few key exercises that I like to use to improve key movements in the sport.

Now that I’ve set up my training to always have exercises being tested against strength and power metrics, I’m able to constantly analyze my training, says @CoachKStrength. Share on XOne thing that I picked up in the last 18 months was analyzing my training. Now that I have set up my training to always have exercises being tested against strength and power metrics, I am able to constantly analyze my training. We have been working with our staff to triangulate methods to improve acute game day performance. We are constantly asking how we can get better and how we can get our athletes better. Intertwining the four coactives becomes a very complex puzzle that we are always trying to solve.

Freelap USA: Collision sports like football and rugby are similar but have unique differences. Can you expand on how each sport has helped you become better at helping the counterpart athlete? What can football learn from rugby and what can rugby learn from football?

Kris Robertson: Rugby and football are such unique sports—for the duration of the game, you are trying to displace another human being by using force, speed, or misdirection. Football was one of my first loves and where I learned what “TEAM” really meant. Football brought me places around the world I would never have visited and allowed me to meet people I would never have dreamed of meeting.

Rugby, although I never played it outside of two years in high school, taught me to think differently. Differently from a sports science perspective: the way coaches, managers, and players understand and accept science is different than anything I have ever seen in football. I have found rugby always changes with the times, whereas football is more a “do what we have always done” sport. Over the past 2-3 years, I have slowly started to see that change, as strength and conditioning coaches in director positions have degrees and not an “I played football, so I know how to train a football player” degree.

One aspect I love about rugby is the continuous nature of the game. I have taken this aspect and now implement conditioning games for my football athletes. We play games such as European handball or rugby for a 3-4 minutes at a time. I have found this a great way to get the athletes to do some fun conditioning games that work on multiple aspects of the game (open agility drills, hand-eye coordination, metabolic conditioning, etc.). From football, I get my rugby athletes to run the wide receiver route tree—catching is a big part of rugby, so I found it is a fun way to switch up the stimulus for my athletes. Throwing back shoulder fades and getting them to cover each other one-on-one helps with overall coordination.

Both sports have their differences, but each sport requires different types of coordination. As coaches, we encourage kids to play multiple sports, then we start to specialize as we get older. Over the last decade, that process has changed due to the professionalization of youth sports. What both sports can learn from each other is the fact that the other sport does exist, and you can use another sport to do general conditioning. Playing other sports in general training will not take away from your sporting skill; it will only enhance it.

Playing other sports in general training will not take away from your sporting skill; it will only enhance it, says @CoachKStrength. Share on XWith our academy athletes, we play basketball, soccer, football, dodgeball, just to name a few. It gets athletes out their groove and requires them to add new tools to their toolbox. Finally, although I stated this already, is what each sport can learn from the other, and every sport can take this lesson and apply it.

Freelap USA: Neck training seems to be stagnating again after concussion prevention has taken a back seat to COVID-19 safety. How do you prepare the neck or plan to change neck training in the future?

Kris Robertson: Neck training is important for both rugby and football, but with my athletes I only implement it in the specific preparation phase. My reasoning for this is due to how quickly I have seen necks become strong; it doesn’t require training it all year-round.

Once we get into the specific prep, I have a continuum I go through with the help of Chris Perry, a physiotherapist I work with on Canada’s Women’s National XV team. Chris has helped me formulate my thoughts around neck training. We go through this continuum with our girls:

-

-

- Yielding isometrics.

-

- Overcoming isometrics.

-

- Sport-specific isometrics (scrum & tackle positions).

- Shock loading (Video 1 below).

Video 1. I implement neck training in the specific preparation phase of training for my athletes. This shock loading exercise acts as a tester—when athletes can do this, their necks are strong and ready.Two to three weeks in each phase seems to be sufficient to help strengthen their neck. The shock loading above is what I use as my tester: When athletes can do this exercise, I feel that their necks are ready. (This is qualitative; I do not have a way of quantifying this.) With COVID-19 and social distancing, shock loading will definitely be off the continuum. But, again, if I continue to do the other stages, I know 2-3 weeks of shock loading will have them ready. All in all, neck training is not a major portion of my training program, but it is there, and I have it at specific times during the training year.

Click here for access to my lection on periodization for my rugby 7’s athletes and to get on the mailing list for other digital courses coming soon.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SFReferences

1. Bompa, T.O. and Haff, G.G. Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training (5th edition). Human Kinetics: Champaign, Illinois. 2009.

2. Kelly, V.G. and Coutts, A.J. “Planning and monitoring loads during the competition phase in team sports.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2007;29(4):32.

-