The Fibonacci sequence is named after mathematician Leonardo of Pisa, known commonly as Fibonacci, and is a series of numbers where the next number in the sequence is the sum of the previous two: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, etc. In nature, the Fibonacci sequence looks like this:

Early in the sequence, the step-by-step changes are fairly linear, but as the sequence develops there are larger transitions in place and the amount of change needed to grow increases. Athlete development demonstrates this same relationship. The time between each victory and real performance change increases substantially. If you only look at the process as a series of outcomes, then the opposite is true, i.e., large changes followed by progressively smaller and smaller alterations. But if we evaluate the process by the amount of growth that occurs then the parallels displayed are fully revealed.

In this article, I will dissect the training process in order to detail and show the type of growth that must occur to achieve high performance, the interdependence of the micro and macro relationship, and the keys to effective planning and action.

Mastery vs. Complexity

In the book, “The 5 Elements of Effective Thinking,” a story is told about a music teacher having his students attempt a more complex piece of music [1]. The students struggle, so the teacher brings them back to a simpler piece of music. They perform it better, but there is still something missing. The teacher then plays the simpler piece, and the nuance of it is fully expressed in his mastery of his instrument. This leaves the students with an understanding of “do less, better” [2]. Dan Pfaff puts this well when he embraces a willingness to reject unnecessary complexity based on current needs, and to simplify tasks, thus allowing for more mastery to occur [3].

The table above compares Edward Sarul, the 1983 World Champion in the shot put, to nine competitors who have all also thrown over 21 meters [4]. While Sarul was slightly stronger in his relative squat, bench press, and power clean strength, the true differentiator was his lifting velocity and the resultant “power” expressed at higher percentages of load. This demonstrates a level of mastery in strength-power expression that could not be matched, even by competitors who achieved >97% of Sarul’s competitive shot put performance.

This level of expertise was not developed by an exposure to maximal loads, but through an improved understanding of the intent to be strong and explosive across the entire developmental sequence. There is a wonderful visual of this in the Werner Gunthor training videos as well. These performances show that it is not a race to maximum weights. Performance is like an orchestra where the key players will vary in their contribution based on a necessary sequence and timing. Showing this commitment to the physical preparation process allows for a fluidity to be achieved where there is no distinction between strength, power, or endurance. There is no difference between warm-up weights and maximum efforts; there is only excellence in the task at hand.

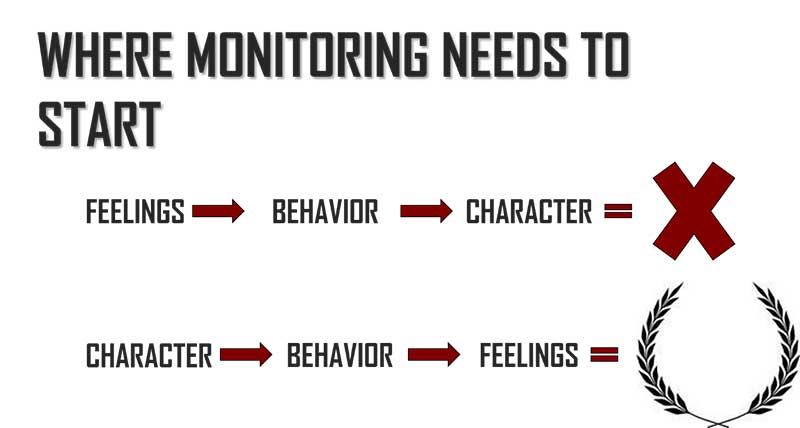

In training environments that emphasize high performance, embedding good process within the culture is critical, especially if that environment is interdisciplinary. A quality process trumps analysis by a factor of six [5]. As such, the clarity of the signal received from the training process in athlete evaluation and monitoring is of the utmost importance. First, leaders need to establish standards and expectations that create an appropriate environment for teams and athletes so they may flourish. This training culture is to talent what soil is to a garden. Second, athletes need to restructure how they view the monitoring process.

It is critical to embed good process within training cultures that emphasize high performance. Share on XMany athletes begin each session evaluating how they feel. This guides their behavior, and ultimately forms their character as an athlete. They need to reverse this strategy and begin with who they want to be as an athlete—this guides their Attitude and Behaviors as the No. 1 thing they can Control (A+B = C), and there is a power developed in the feelings they then have [6].

Training Process and Workload Distribution

The O-O-D-A loop—short for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act—is a decision-making framework that can guide the development of such a training environment. This approach focuses on agility over raw horsepower [7]. The OODA loop allows practitioners to know what matters, through athlete observation and monitoring; to measure what matters, through needs analysis and testing; and to change what matters, through the impending decisions and action taken [8]. Each phase of the OODA loop also allows for alternative pathways to be used to re-orient the process when necessary. The OODA loop optimizes process and knowledge of results, and performance can be evaluated immediately, leading to the next logical iteration.

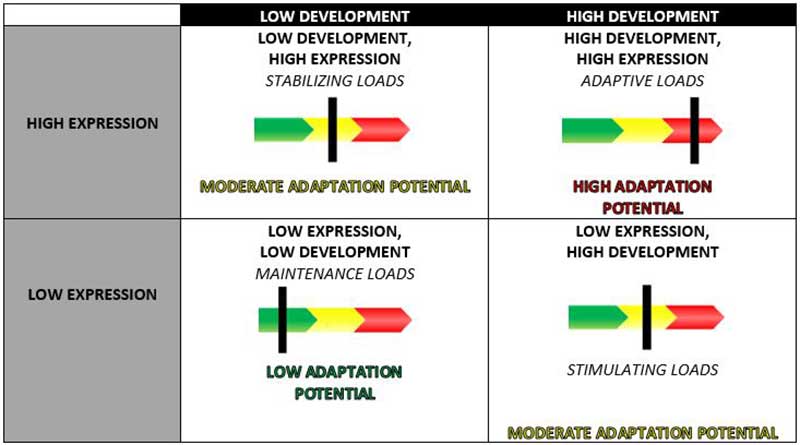

In applied environments, the challenge is generating the right training stress, at the right time, in a way that allows for the appropriate qualities to be developed and expressed specific to current needs, but done so that we are also working toward a team and athlete’s ultimate potential. Whether training loads focus on developing or expressing a current power or capacity indicates the kind of adaptive potential those specific loads have.

Maintenance loads seek to neither develop nor express a high percentage of current power or capacity. They function to remove fatigue so adaptation reserves can be concentrated elsewhere or so the athlete can make a more fluid transition towards another season or training phase while minimizing losses of fitness [3].

Stimulating loads concentrate on either an acute or chronic potentiation of training to develop greater power or capacity.

Stabilizing loads focus on spending more time with a recently developed power or capacity so that quality can be expressed with greater consistency. It is important to note that expressing that quality with such consistency does, in fact, lead to the development of a general, special, or specific work capacity. This occurs within a narrower window of adaptation and, as this commonly occurs in performance, represents a gray area in development.

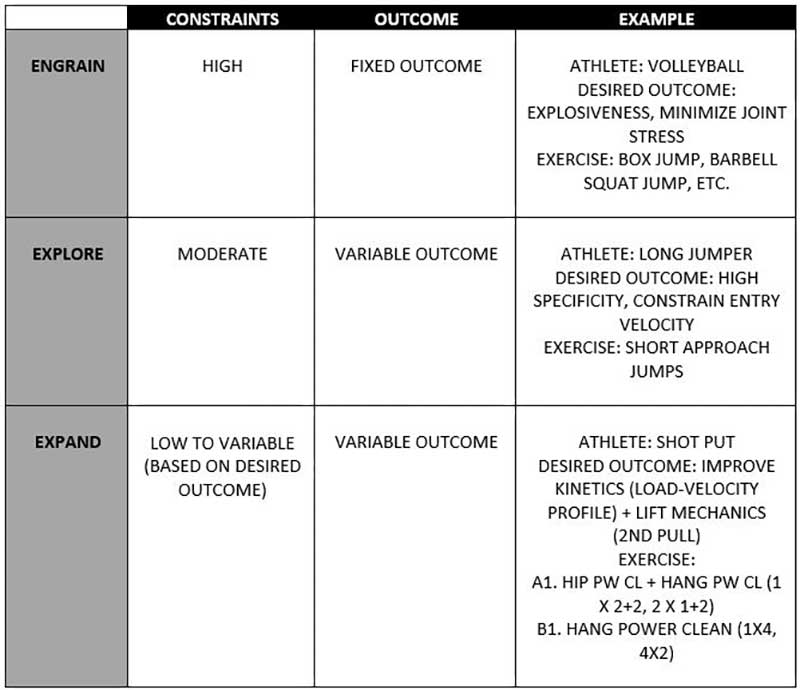

Adaptive loads take athletes to the absolute edge of their ability. As such, athletes must be observed and monitored closely, and such loads should be reserved for those who have technique that is well-engrained [9] (Table 3). These loads have the potential to help athletes to greatly explore and expand their current power and capacity capabilities, and should therefore be aligned with current development or expression needs.

This process basically represents redlining, and the time spent pushing the envelope in such a way is dependent on previously demonstrated resiliency and an athlete’s current form. At the high-performance level, this intensity is not an option, but it has to be intelligently planned and performed. This type of intelligent action can be demonstrated through a backbone of sport science: When you are attempting to push limits in this way, why guess what an athlete is capable of when you can know for sure?

Periodization that can coordinate athlete monitoring, the potentiation of our current training phase by the last phase, and the optimization of preparedness towards a targeted physical performance can be defined as fluid periodization [10]. This fluidity is adaptive readiness personified. It represents the willingness to embrace the knowledge of the athlete’s ultimate goal and their current capabilities, and then align training so they can give their absolute best to today’s loads based on planning and our ability to execute that plan.

Today, this intent is represented with what is commonly accepted as best practice, where monitoring directly influences the day-to-day training performed, based on specific “windows of adaptation.” However, athlete observation and monitoring has always been important to good coaches and this has been reflected in how they have approached microcycle construction (e.g. high-low models, vertical integration, etc.).

A good planning and training process anticipates the need for alterations in day-to-day training in advance, and considers issues of compatibility and complementarity in design, in line with the slogan of the Israeli Defense Forces, “Plans are merely a platform for change.” [11] Do not let language that sounds new and different allow you to forget what you already know.

Program Structure and the Contingency-Necessity Model

The question must then be asked, “What does this actually look like?” Reconciling the differences between research settings, where clarity and constraints are high, and applied environments is a huge leap. Resources are often limited and this negatively influences process and a training program’s capabilities. In the field, predicting training responses is far less certain. Insights from research must be tempered against that which you are more certain of.

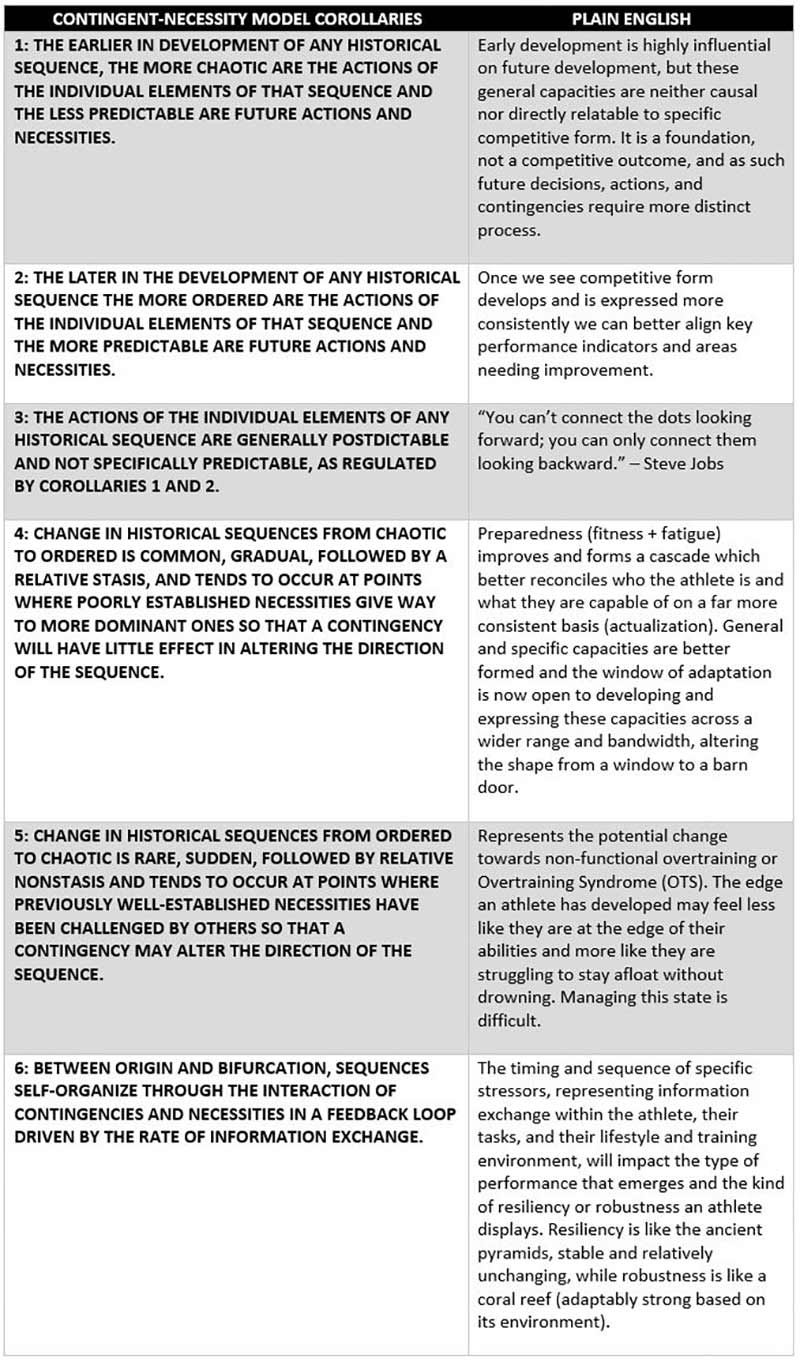

A challenge exists in weighing sport science and research insights against training performance. Share on XA challenge exists in weighing sport science and research insights against performance in day-to-day training environments. This is where the contingent-necessity model can help practitioners achieve greater clarity (Table 4) [12]. The contingent-necessity model lays out a rationale that shows why contingencies, i.e. future events and circumstances, may interfere with good process through things that are outside of our control as practitioners. But, more importantly, the contingent-necessity model also includes necessity, or constraints, as those things that can work for and with us to better control and direct development in the short-term, notably the laws and theories of physics, biology, and pedagogy.

No one knows what results an athlete will ultimately achieve or the failures they will endure. But we can use current sport science knowledge to establish the environment, standards, and expectations, so we are best prepared for contingencies. We can then integrate science with the art of coaching to create a shared consciousness that gives the training urgency and an initial momentum.

We use necessity and constraints to:

- Test and monitor changes, weighed against standards and expectations in the short and long-term; and

- To allow for the maximum development and expression of specific qualities, but done so implicitly so we can focus much of our language on team, communication, and successful collaboration.

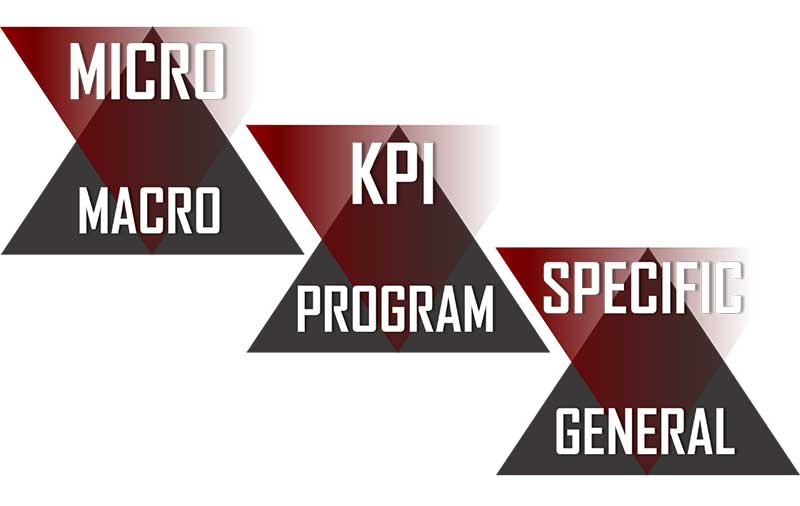

Collaboration is about developing trust, affirming a joint purpose, and demonstrating excellence in the work together. This approach overcomes the cynicism many coaches have for sport science with a pragmatism applied in the day-to-day work performed. This is how the micro dictates the macro, how the key performance indicator (KPI) eventually outweighs the program, and how the specific complements the general (Figure 3).

Long-term development is as much a function of enhanced training quality and the clarity of the signal generated, where micro dictates macro, as it is dependent upon minimizing or reducing the impact of problems and interference (contingency-necessity). In the early stages, the program takes precedence over KPIs, but this should quickly change as we achieve more meaningful insight into an athlete’s adaptation process through the coordination of training, testing, and the athlete monitoring process. As we move closer to key competitions, specificity increases and general loads now function as an “anti-virus,” like software in a computer functioning to keep things operating efficiently [13].

How these loads are vertically integrated and horizontally summated is like the ripple effect of a stone thrown into a body of water. This, again, is how the micro dictates the macro, and shows us that, in the moment of victory, having paid the price of what it takes to win is all worth it when the work you have put into the process generates a clear and successful outcome.

References

- Burger, EB and Starbird, Michael (2012). The 5 Elements of Effective Thinking. Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey.

- McKeown, Greg (2014). Essentialism. Crown Publishing Group: New York, New York.

- Pfaff, Dan (2006). “Training Theory” and “Chronic Loading” Lectures. The Canadian Athletics Coaching Center.

- Cronin, J. and Sleivert, G. “Challenges in Understanding the Influence of Maximal Power Training on Improving Athletic Performance.” Sports Med 2005; 35(3); 213-234.

- Lovallo, Dan and Sibony, Olivier. “The Case for Behavioral Strategy.” McKinsey Quarterly 2: 30-45 (March 2010)

- Greitens, Eric (2015). Resilience: Hard-Won Wisdom for Living a Better Life. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA.

- Coram, Robert (2002). BOYD: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War. Back Bay Books: New York, New York.

- Jordan, Matt (2016). “Functional Asymmetry and Eccentric Deceleration” Webinar. Jordan Strength.

- French, Duncan (2015). “Advanced Power Techniques” Lecture. NSCA Coaches Conferences: Louisville, Kentucky.

- Martinez, DB (2016). “The Use of Reactive Strength Index, Reactive Strength Index Modified, and Flight Time: Contraction Time as Monitoring Tools.” J Aus Str & Cond 24(5): 37-41, 2016.

- Sands, WA, Apostolopoulos, N, Kavanaugh, AA and Stone, MH. (2016). “Recovery-Adaptation.” NSCA SCJ 38(6): 10-26.

- Sands, WA and McNeal, JR. “Predicting Athlete Preparation and Performance: A Theoretical Perspective.” J Sport Behav 23: 1–22, 2000.

- Evely, Derek. Modern Trends in Periodization. HMMR Media: Feb 2016.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Prof Prem raj Pushpakaran writes — let us celebrate 23rd November as Fibonacci Day!!!