When you are about to embark on a journey with a group of athletes, such as at the start of a season or with a new intake of school or college kids, what is the first thing you do? Most of you would probably answer that question with one word: plan. As suggested by the famous Abraham Lincoln quote about being tasked with chopping down a tree, it’s in our best interests to not jump straight into doing random training and instead spend a fair bit of time sharpening the axe.

Within the strength and conditioning field, planning is often synonymous with the term “periodization,” and with that comes a large body of research underpinning it, says @peteburridge. Share on XWithin the strength and conditioning field, planning is often synonymous with the term periodization—and with that comes a large body of research underpinning it. When devising my own training plan, I always have the endpoint in mind and need to ask what is the end goal? Then, I can best plan the route to take my athletes on and make sure I understand where any potential pitfalls may lie along the way. Working with academy rugby players, the best way of summing up my ultimate purpose is:

To build the general physical capacities, to give athletes the platform to express their rugby skills, and ultimately to progress through the pathway.

The outcome is obviously progression through the pathway, but it’s more about the process. I need to provide the guide rope and get them to the top of the mountain to “make it” as a rugby player. Obviously, rugby is king in this process, so it doesn’t matter if they squat 300 kgs and can finish the beep test—if they aren’t any good at rugby, then those physical qualities are useless.

First Step: Performing a Needs Analysis

For each athlete I work with, I have to ask the question: Where are the movement skill gaps? What deficiency in movement skill is going to limit their progression through the pathway? Then, how can I fill these gaps to help them climb up the mountain? For example, rather than looking at it just through the lens of an S&C coach—do more deadlifts or improve their clean numbers—I need to look at it with a top-down approach, putting rugby first.

For instance, it might be that a player can’t drop his body height to effectively tackle. Or, in football they may not possess the braking ability to handle the high number of intense decelerations to play the high pressing game that many modern top sides employ. The remedy may still be to improve their squat or deadlift, but I have to look at it from the movement skill first and then work backward from there rather than just chase ever-increasing squat numbers and hope it all just magically transfers to the field.

From there, I need to do my best psychic impression and a bit of “forecasting.” This is because rugby as a game is developing at a very fast rate: In only 10 years the game has changed tremendously, with the physical demands becoming much, much more substantial.1 In all sports, players are getting bigger, faster, and fitter, but in rugby it is exponentially so, in part because the game was amateur only 25 years ago.

You only have to look at clips from the All Blacks of yesteryear versus the All Blacks now to recognize we are dealing with very different animals! With that in mind, if I have a player come into our system at 16, in all likelihood he will be around 22 by the time he breaks into the first team. The game may be completely different in six years’ time, so I need to also think about what challenges and movement skill problems the player will face in the future game.

Finally, in this needs analysis I have to do some problem solving—Why does the player possess this movement skill gap? Is it that he can’t, he won’t, or he doesn’t know how? This then dictates our strategy and how we set up the long-term plan, as well as the medium- and short-term plans (macro, meso, and micro cycles, for all the periodization purists out there!).

Applying the Needs Analysis in Training

As a rugby example to explain this process, let’s use the skill of jackaling (which you can see on the pitch in this montage). This is where a player competes at the breakdown to steal the ball: It requires speed, decision-making, strength, mobility, and a mindset to get whacked by an opposing player while in a vulnerable position.

- It may be that a player can’t: He doesn’t have the hip mobility to get into that jackal position and maintain his balance, and so may need to work on his mobility to make improvements to his body height and body position.

- It could be that he won’t: Perhaps he has gotten injured in that position previously and there is some apprehension to get into that position again. (A quick YouTube search of “jackal injuries” brings up some quite gruesome highlights.) In this case, I may have to reduce the risk and slowly expose him to more “live” competitive situations to build confidence. Then, expose him to some outcome success (through constraining drills and training) to get him to be more willing to do it. Failing that, if it’s a deeper psychological issue, then I may have to enlist a sports psychologist to help him get over the mental block.

- It might be he doesn’t know how: He may not possess the decision-making skills to read the game to know when to go for the ball or not; he may not know how to put his body in a position to be successful and easily gets counter rucked off the ball. Enlisting the help of expert technical coaches is key to helping fill this gap.

Getting the player faster may give him more time to process the cues to make better decisions. Extra strength could also allow him to get away with poorer technique, similar to the old Russian weightlifter adage: Technique is for the weak. (That quote works better with an Ivan Drago accent!) Again, it still might lead to squatting and cleans (if that is your chosen tool to develop these general physical capacities), but at least you’ve arrived at that decision from a much more informed place to get them better at the key bit—rugby!

Once we understand what the movement skill gap is, we can then go about purposefully attacking it with our training. However, we must always be aware that making a change in the body always carries with it a cost, and we must take this into account when making programming decisions. When the player has progressed through the pathway into the first team, where fixtures are regular and freshness is key, doing a large amount of physical development work will steal from the player’s freshness for competition.

With this in mind, more costly exercises are better performed at the development stage where there is less game pressure. Meaning, it’s better to sacrifice a bit of freshness now at the developmental stage because winning isn’t the main goal. Often, this takes some education at first, but when they trust the process (#TTP!) they understand my mantra:

You’ll play at 95% today so that you can play at 110% in the future.

(What does our academy training look like? You can see our club’s performance environment in-depth in this longer video here.)

I’m going to take advantage of the window now when game pressure is lower by being more aggressive with players’ training and looking to (safely!) push the boundaries, so that when they do become a full-time professional, they don’t have to do as much work to maintain what they already have. At that point, as they get older, they can bias their training more toward freshness.

There is actually some cool science to support this: It takes around one-sixth of the work to maintain what you have once you’ve got it than what it takes to initially achieve it.2 What does this mean? It takes me far less time to stay squatting 150 kgs than it does to work up to getting there. Due to this phenomenon, when working with a younger athlete, if I can bias my training toward development over freshness it will pay off in the long run, as I won’t have to invest as much time to maintain strength levels.

Practical Periodization Strategies

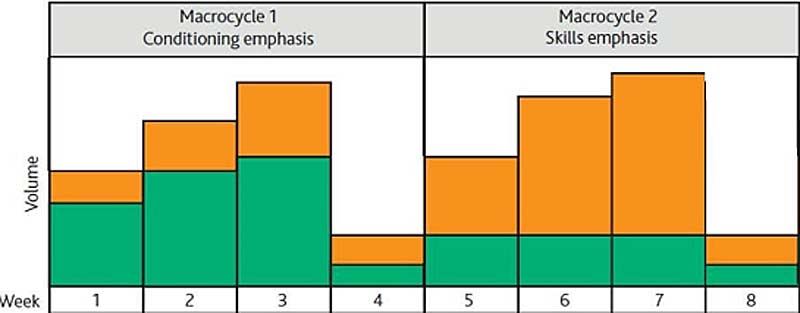

One of the best ways of managing the cost of training is with designated training windows where a real focus can be put on physical development. This has an added positive effect because restrictions to on-field training vastly reduces the players’ energy expenditure, providing a ripe environment for growth.

Let me ask you a question: As a coach, how often are you faced with the situation where you get access to an injured player for an extended period of time and they come back much stronger, having put on lots of size because of that extra development time? Why should we wait for a player to get injured to have this in their development plan? If physical capacity might be what stops them progressing through the pathway, why not combat it early when you can? The only way you can get that opportunity is if you have smart coaches who trust you and understand the overall holistic development of a player.

This thought process is what I imagine many of you already employ when working with your athletes. However, when you first learn about periodization, it can be very easy to be blinded by the long terms, fancy bar charts, and mystical Soviet methods.

In fact, early in my career I went on a CPD trip across Florida to many college programs and professional sports franchises for some further learning. When I got there, the first question often asked of me was: What system do you run? I was a bit baffled by the question, but I put on my polite British voice and tried to answer. When we got into further discussion, the coaches I spoke to basically wanted to know what periodization strategy I employed. Did I follow a conjugate method? Had I ever reverse-periodized? Did I set my program up to be high to low, or low to high? I took a stab at an answer that really meant uhhh…It depends.

Does it have to be that complicated though? All periodization means in my eyes is the systematic planning and sequencing of athletic training to maximize either performance or development. Why do I have to pick a side with something as simple as the planning and sequencing of my training? As long as I can justify why I am doing what I do, does it really matter if I’m #TeamUndulating or #TeamBlockPeriodization?

Obviously, this isn’t a swipe at many of the “Original Gangsters” of our field like Hans Selye, Leo Matveyev, and Tudor Bompa, who were the godfathers of the field when it came to periodization. Some of their work still informs a lot of what I do today, and Tudor Bompa’s textbook, Periodization, was actually the first book I ever took out of my student library at university. However, these “systems” were built upon the assumption that the body adapts to stress placed upon it in a fairly linear way, and working with young team sport athletes has shown me that at times this can be a little too rigid to follow my purpose stated above.

Having an understanding of the era that these models were born out of can provide a bit more context for why they may have built their “system” in the way they did. Grigory Rodchenkov (Russian anti-doping advisor and inadvertent star of the Netflix documentary Icarus) shed light on his use of different periodization models when he said: “Doping begins when harm from their heavy training workload becomes more dangerous than harm from using doping.”

Considering that much of the work on periodization came from this era, it has far-reaching consequences for you if you try to blindly follow these methods. Suddenly trying to get your athletes to “do Smolov” to get them strong or do “German volume training” to get them big may not be the best long-term way to set up someone’s training. This isn’t to tarnish some of the great work done by these coaches, but what’s best for a doped-up ’80s Eastern European shot putter might not be best for an 18-year-old rugby player!

Periodization Then & Now

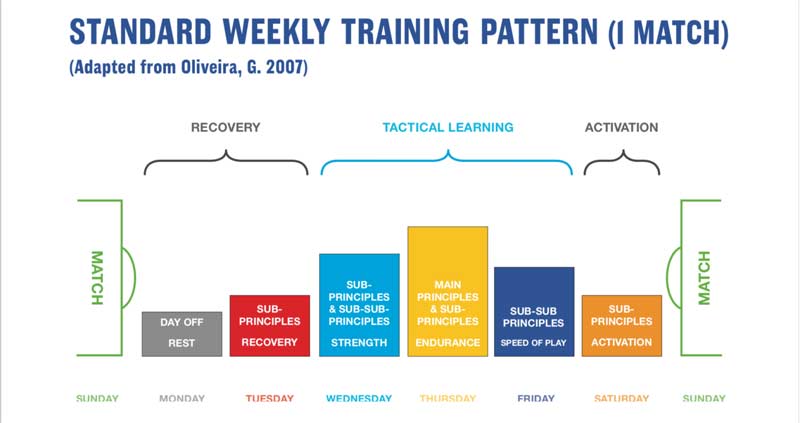

After initially starting out in the Eastern Bloc, in more recent times periodization research has been further developed in Western Europe by researchers from Portugal and Spain, such as Victor Frade and Alberto Mendez-Villanueva, who introduced the concept of “tactical periodization.” Whereas some of the classical Eastern methods often take a very physical-centric view of planning training, these methods aim to piece together the technical-tactical element alongside the physical one. This perhaps aligns better with the more holistic view of performance planning I mentioned above.

Tactical periodization is the zeitgeist of sport science at the moment, and has started to gain greater attention with coaches like Jose Mourinho (football) and Eddie Jones (rugby), who have implemented it with great success in their respective sports. However, much like if you were to put 10 S&C coaches in a room to decide whether conjugate or undulating methods are best, you would get just as much disagreement if you were to ask how to best implement tactical periodization.

When implemented well, at its best it encourages a joined-up, multidisciplinary approach to training planning linked heavily to the head coach’s game model/philosophy. This can lead to a top-down approach to training, where physios, strength and conditioning staff, and technical coaches no longer sit in silos operating as separate entities. Instead, the approach more readily encourages the multidisciplinary team to work together with an aligned vision.

At its best, tactical periodization encourages a joined-up, multidisciplinary approach to training planning linked heavily to the head coach’s game philosophy, says @peteburridge. Share on XHowever, sometimes tactical periodization gets held up as an argument (often in football) against any “true” physical-based training by sport coaches. This negative view of gym-based training has helped foster a culture of noncompliance in professional football to physical preparation occurring anywhere outside of the training pitch. This may be one of numerous reasons why hamstring injuries have, in fact, been increasing despite lots more research into preventative strategies.3

There is growing evidence, however, that periodization isn’t as big a deal as I was led to believe when I was a junior coach. For example, John Kiely argues that periodization in the classical textbooks takes too much of a biological view of the body and that, in fact, things like genetics, psycho-emotional state, cognitive state, and numerous environmental factors play just as much of a part in dictating the adaptation that we get from training.5

Furthermore, some studies have shown that there were no differences in strength or muscle mass following 16 weeks of periodized or non-periodized approaches to training.6 Norwegian researcher Thomas Haugen has shown that there are big differences in elite sprint coaches’ approaches to periodization, and argued more people in the sprint world are becoming skeptical of classical periodization models.7 Finally, some prominent track coaches have offered up some choice words on the topic, such as Jonathan J. Marcus: “All periodization models are wrong. They are too complex and don’t work.” In addition, Tony Holler has said: “Periodization is bullsh*t…we sprint always.”

Taking all of this contemporary research in, I think blindly following a classical method because it appears in a textbook may be an over-simplified approach. For starters, why in every traditional periodized plan is there a down week on the fourth week? (The cynic in me can think of one pharmaceutical reason!) What if my athlete is dominating his training in week 3, but I have to back off in week 4 because my “system” dictates he should have a down week? On the flip side, what if in week 2 he is already too fatigued from the training, but in week 3 I have an “overreaching week”? Am I meant to carry on driving the athlete into the ground, risking poor performance and injury because my “system” says I should?

For coaches who don’t work in Olympic sports, the likelihood of you running your program in sequential blocks building toward two or three competitions is very low. A much more likely scenario in team sports is a game every week. It gets even worse in sports like football or basketball, where you may have games every three or four days! How on earth are you meant to peak and taper on a macro level like that if you have big games week-in and week-out?

Key Considerations in Training Teen Rugby Athletes

On an individual level, biochemical factors linked to nutrition and sleep play a much larger role in an athlete’s ability to adapt to training than classic periodization models account for. For example, when working as a university S&C coach, I knew that the first two weeks of the year were “Freshers Week.” In England, this meant my athletes would be consuming copious amounts of alcohol, getting minimal sleep, and partying for at the very least 6 out of those 14 days. No matter how I’ve drawn up my blocks of training, this reality is going to affect the adaptations I can get from the training and I had to account for it.

Often, we overstate our impact as coaches and don’t give enough credit to the role of someone’s genetics in determining the adaptations we achieve. The systems of talent development now are designed to force the cream to rise to the top, and in team sports everyone at the top is a freak. It’s just the way it is.

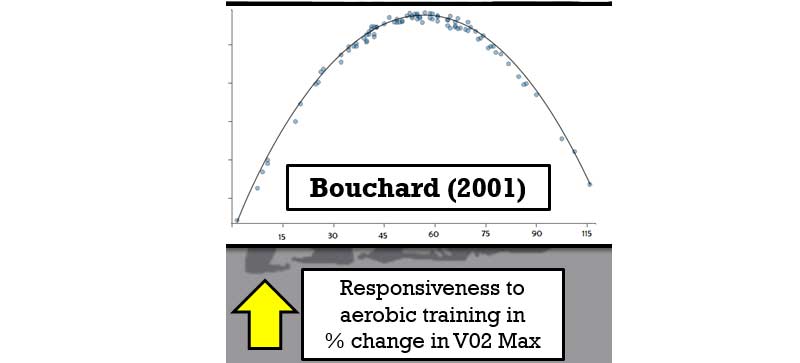

Often, we overstate our impact as coaches and don’t give enough credit to the role of someone’s genetics in determining the adaptations we achieve, says @peteburridge. Share on XOne glance at the NFL Combine numbers shows that to succeed in the NFL, you likely have to be a genetic beast. It’s not that they had a better periodized plan, it’s just that they had better parents!! There is a large body of research showing that responsiveness to training is largely dictated by genetics: For example, the HERITAGE study showed the level of responsiveness to the same aerobic training is drastically different when looking at the % improvements made in VO2 max.8

When working with academy players, I have the added element of academic stress that can affect someone’s responsiveness to training. To complicate things further, there are large individual differences within the group. For example, I might work with an athlete who is stressed out of his eyeballs as he tries to get the grades to go to Oxford or Cambridge. Equally, I will have athletes who subscribe more to the Cardale Jones philosophy of schoolwork—they don’t “come to play school!” With these guys, I might not need to change their training at all; however, with the future Cambridge student, I may need to reduce the volume of his training while he focuses on getting into medical school.

Working with adolescent boys, there is another key stressor outside of rugby and academics for me to contend with…girls! Both in a good and bad way. I’ve had spikes in life stress caused by athletes breaking up with their girlfriend, and as a coach I’ve had to play the role of counselor. Equally, I’ve had a few occasions where the wellness monitoring has shown up as sleep 2/10, but mood 10/10. I will let you work out the probable cause of that!

The lesson here is that when sitting down to plan out your training, can you really account for a player struggling with a breakup or something quite the opposite? Taking a more flexible, agile approach better allows you to navigate these scenarios. That way, you can ride those waves of emotion and better target the windows where your players are in a positive state to adapt to training.

Using monitoring tools can help this, whether RPEs, questionnaires, velocity-based training, sub max bikes, jumps, or the best monitoring tool going: talking to the player. These can all be keys to glean information to tweak and adjust your programming. Sometimes, the simple question how are you feeling today? can give you all the insight you need to effectively change your training plan. Often, far better than any wellness or RPE Z score ever could.

Hearing these criticisms, you are probably thinking that I don’t “do” periodization, and that I now have to be struck off the UKSCA and NSCA accreditation boards forever! The answer is that I just take a much more reactive approach. There is still a training plan, but it is way more fluid. You have to know your players and pinpoint times of the year where you think you know how they might respond, but build fail-safes into your program to allow flexibility. If I just hammer on with my periodized plan without factoring in all these things, I will run into issues that hamper my athletes’ development.

My Approach to Periodization

Where possible, you want to provide a high-potency/low-cost stimulus, so if you can pick up technical/tactical outcomes alongside a conditioning stimulus, you’ve saved some of your training budget to be spent elsewhere. This is the beauty of a tactically periodized approach with coaches who understand what you want as an S&C coach as much as what they want as a technical coach from a session. A secret of our academy is we do very minimal conditioning sessions. Why? Well, if your training on-field is at a good-enough intensity, then you won’t need to. Obviously, through the year you’ll have guys who need top-ups or individuals with a specific need, but whole team-based conditioning? If you can get it from rugby, why layer on more fatigue?

The number of other things you have a chance to develop doing it this way is huge for a developmental athlete. You can still introduce them to the #Grind™, but if they get a chance to work on their decision-making and tactical understanding too, surely that will lead to better outcomes? For example, you can have someone who can complete the beep test or knock out monstrous scores on the watt bike, but if they don’t do the “rugby” bit, it’s pointless! This is where small-sided games and utilizing constraints such as rules, dimensions, and tasks help promote both physiology and skill development.

This approach could be seen as a dangerous one to adopt in professional sport, especially with coaches and senior management challenging performance departments with “we aren’t fit enough” so regularly. I could write a 10,000-word essay deconstructing that entire comment, but often these comments are suspiciously linked to the win or loss column. Fitness obviously is a contributing factor to performance, but often rather than just doing mindless conditioning, the best kind of conditioning is being so good technically and tactically that you never waste energy making mistakes or being in the wrong position.

This leads to a mixed approach, where both S&C and technical coaches need to work together. If you look at some of the greatest in their sport, like Lebron James and Lionel Messi, they are expert walkers. They know how to conserve their energy for times when they really need it. Equally, because they so rarely give the ball away, they don’t actually have to work that hard in transition because the pass always hits the mark, or the shot always goes in!

The key message here is that the sport is king, and often being less-accomplished technically or tactically can be perceived as a “fitness” issue. I had one such experience working in football when a player was substituted in part because the coach wasn’t happy with his physical output. His GPS, however, showed he had done more high-speed running than any other player, by some margin. The problem was he kept giving the ball away and having to run the length of the field tracking back! Now, he’s shown me he was capable of a far greater physical output than anyone else, but the issue was he needed to do so much because he was so bad technically! Was this a fitness issue, or would he be better off working on his passing so that he didn’t have to keep physically covering for his technical errors?

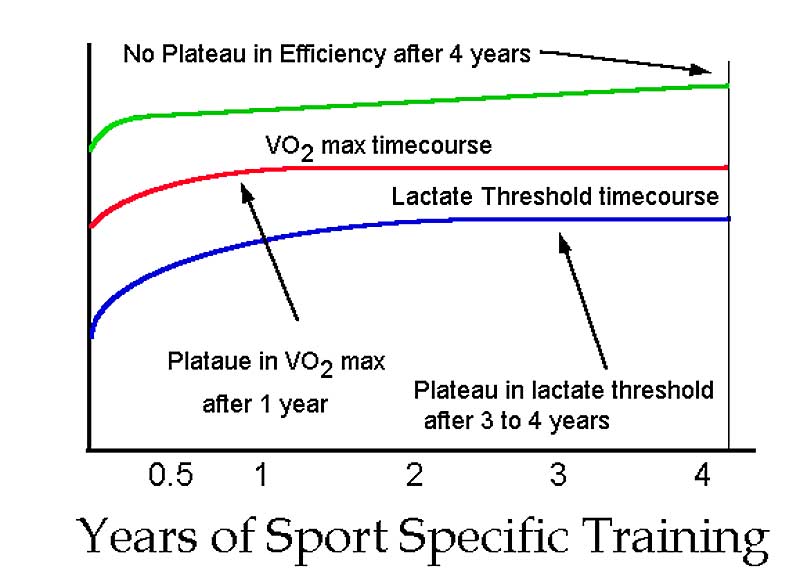

One of the other reasons that we do “less” conditioning at the younger ages is that the time for increases in VO2 max training is very short—a week even! But these athletes plateau after about six months. If the central adaptations (i.e., their VO2 max) isn’t quite fully developed but takes only six months to develop fully, I would rather that than them having a strength or hypertrophy “gap” that takes a much bigger training investment. It takes time to put on good-quality muscle mass, and this is time they probably don’t have at the first team end, where they need to be playing and contributing at their absolute best because winning matters more at that level. So, there is no better opportunity to push toward a strength-focused program than when athletes are young. When you get a window of opportunity, take it!

Despite the heavy investment, those strength improvements stick around longer. For example, once you’ve laid down satellite cells, they stay with you for at least 15 years, if not your lifetime.9 Due to strength underpinning so many athletic actions, if I can lay a good foundation early, I equip my athletes with the “master key” to unlock all movement skill doors. This then allows them to have the physical capacity to solve any movement problem that the sport throws at them. Not only that, it also equips them with a coat of armor to withstand the rigors of the sport, keeping them on the field and off the treatment table. This then gives them even more opportunity to hone their skills and develop on the field.

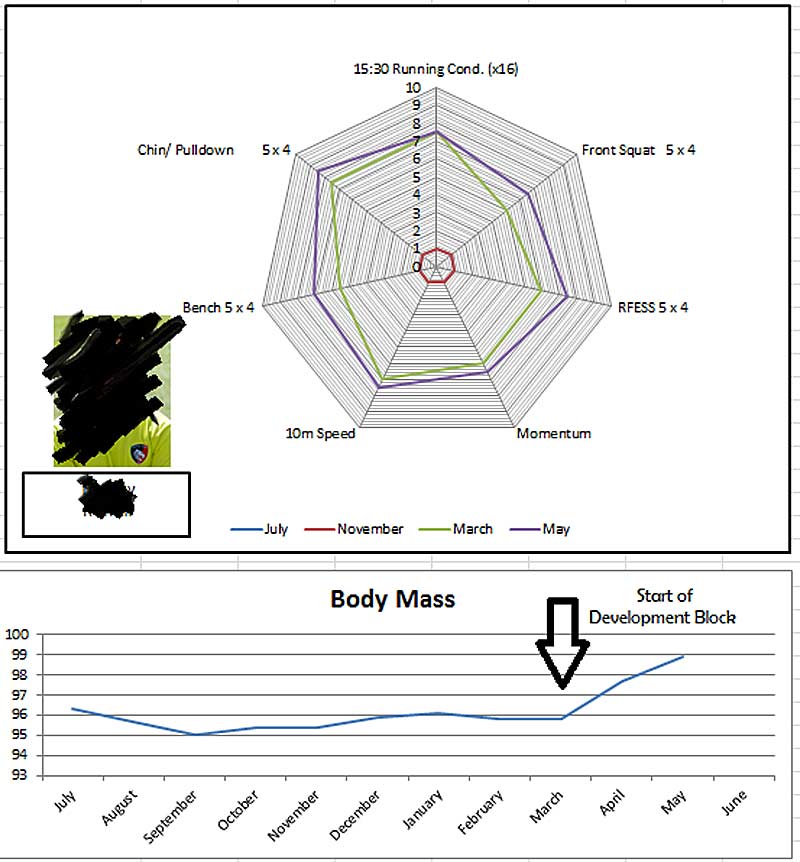

What It Looks Like

I view my training planning through three lenses:

- The satellite view

- The helicopter view

- The magnifying glass view

This allows me to stay flexible for all the bumps in the road with my programming, but it still gives me a rough idea of where I want to be in the end.

The ‘Satellite’ View

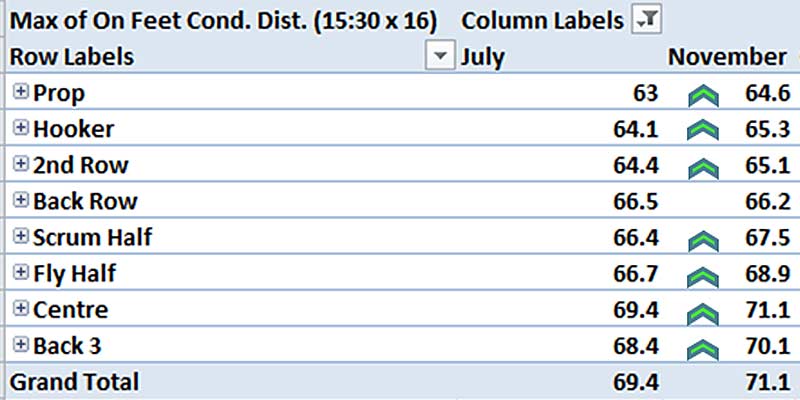

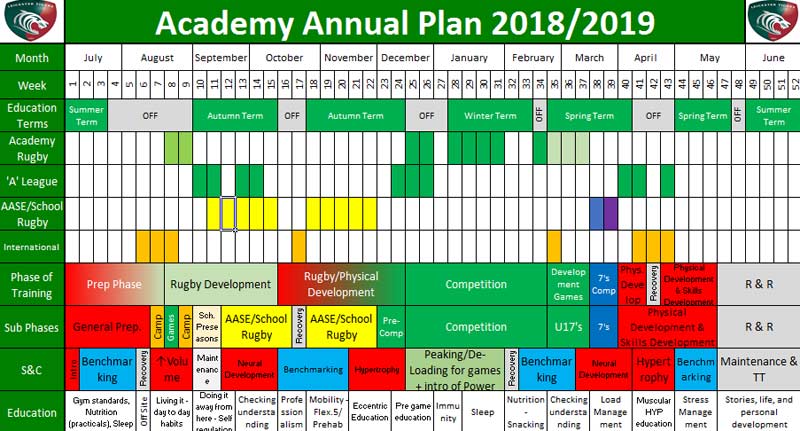

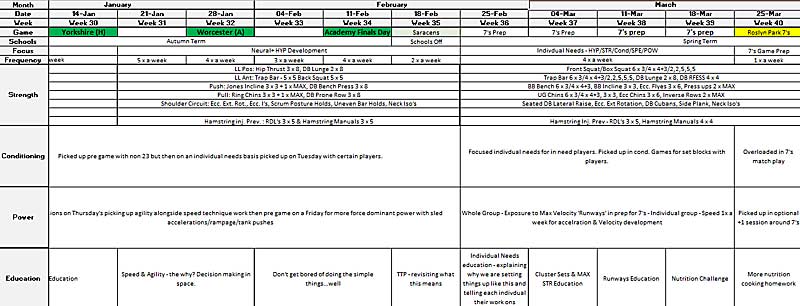

Figure 8 shows my annual plan. This plan might look nice with fancy colors, but in fact it changed multiple times through the course of the season. It gives me rough ideas of typical windows where I can be more aggressive and other red flag areas where I might need to reduce the athletes’ training load. Periodizing their education to align the pertinent messages is something I would recommend for all development-level coaches to add to their program so that players get a deeper understanding of how to behave like a professional.

The ‘Helicopter’ View

My monthly-based plan, as seen in figure 9, is a little bit more focused, as it shows more detail. This gives me a base idea of what I’d ideally like to do and what the focus of the block is, but this is where things change quite a bit. Often, I plan for, say, a four-week block, but it works so well that I may extend it to a five-, six-, or even seven-week block.

The ‘Magnifying Glass’ View

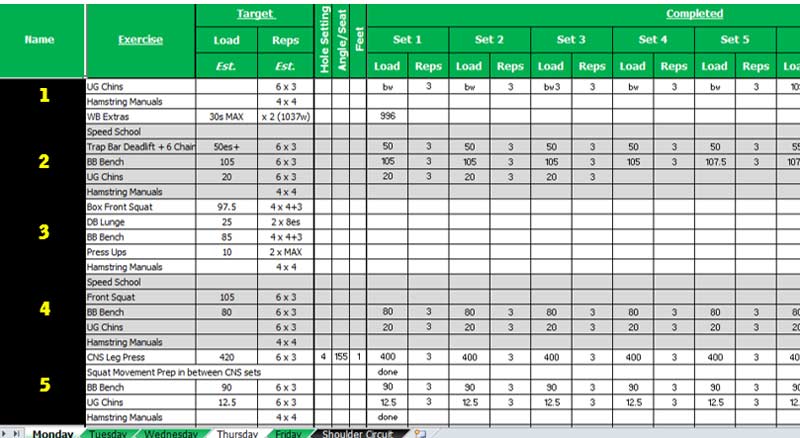

My weekly plan (figure 10) is what the athlete sees day-to-day. You’ll notice that different athletes do different lifts outside from a one-size-fits-all program and a few tweaks made in-session different from the daily plan. For example, if we look at Athlete #5, he didn’t meet the prescribed load for his lower limb exercise because he came in beat-up from the games, and we had to reduce the load lifted. This may not have fit my fancy periodized progression graphs, but it was the athlete I had to coach on the day so that’s what happened. Equally, Athlete #2 ended up outlifting his prescribed load because he was feeling good that day. Having an adaptable plan is key so I can constantly make adjustments on the fly.

All in all, periodization probably doesn’t need to be as complicated as some make it out to be, and “classical” periodization is probably too linear and too rigid for team sports. You absolutely need a plan, but you don’t want to be completely married to it. Finally, when looking at the year as a whole, you should consistently hunt for opportunities and threats to the plan and tweak it to meet the needs of each individual you work with.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Dubois R, Paillard T, Lyons M, McGrath D, Maurelli O., and Prioux J. “Running and metabolic demands of elite rugby union assessed using traditional, metabolic power, and heart rate monitoring methods.” Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 2017;16(1):84–92.

2. Bickel CS, Cross JM, and Bamman MM. “Exercise dosing to retain resistance training adaptations in young and older adults.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2011;43(7):1177–1187.

3. Ekstrand J, Waldén M, and Hägglund M. “Hamstring injuries have increased by 4% annually in men’s professional football, since 2001: A 13-year longitudinal analysis of the UEFA Elite Club injury study.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;50(12):731–7.

4. Oliveira JG. F.C. Porto: Nuestro microciclo semanal (morfociclo); VI clinic fútbol, base fundación osasuna. 2007.

5. Kiely J. “Periodization theory: Confronting an inconvenient truth.” Sports Medicine. 2018;48(4):753–764.

6. de Freitas MC, de Souza Pereira CG, Batista VC, et al. “Effects of linear versus nonperiodized resistance training on isometric force and skeletal muscle mass adaptations in sarcopenic older adults.” Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2019;15(1):148–154.

7. Haugen T, Seiler S, Sandbakk Ø, and Tønnessen E. “The training and development of elite sprint performance: An integration of scientific and best practice literature.” Sports Med Open. 2019;5(1):44. PubMed ID: 31754845 doi:10.1186/s40798-019-0221-0

8. Bouchard C and Rankinen T. “Individual differences in response to regular physical activity.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2001;33(6 suppl):S446–51;discussion S452–3.

9. Gundersen K. “Muscle memory and a new cellular model for muscle atrophy and hypertrophy.” The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2016;219(2):235–242.

What a cracking article Pete, even for us involved in clubs at the lowest tiers of the sport there’s a lot to be gleaned and very refreshing to hear that such a “common sense” approach with young academy players is working-reminds me of my time involved in Royal Navy Phase 1 (basic) training a few years back.

Wow!! What a brilliant read! Thank you!