Have you noticed that we see either the lowest introductory level jumping exercises or the holy grail of BIG BOX JUMPS? Do you ever wonder what happened to the medium intensity jumping sequences and where they fit into your program?

Let’s find a home for this stepchild of plyometric intensities—the middle-intensity jumps. WARNING: Your cool factor on social media might take a drastic hit because you’re not jumping onto a 50-inch stack of Olympic plates swaying back and forth as you go into your approach.

The Gap Between Beginner and Advanced Jumping Exercises

Recently I wrote a post on using very low boxes for training, 2-4 inches in height, to elicit a very reactive response to ground contacts. I shared how these lower level, yet extremely quick, actions could be used vertically, horizontally, and lateral specific. It was a pretty cool article if you want to check it out to gain perspective on low box training.

Although the strategies used in low box training stand on their own, they’re also great to use in the early stages of building a foundation of the foot, ankle, and lower leg strength, plus power and elasticity when preparing your athletes for higher-level plyometrics.

Logically, the next progression in the sequence of jumping is to add more intensity—let’s say more potential knee bending and a little less focus on elastic energy. To do so, we’re going to graduate our athletes up to more medium-height jumping, including medium-height boxes.

Keep in mind, as we go up in height, we slowly eliminate the lateral influence of change of direction type elastic work. But that’s perfectly fine. And it’s a good thing because the higher we go and the more intensity we drive, the less variability we want so we can safely produce force at appropriate angles—while protecting our joint systems.

Okay, what do I mean when I talk about medium jumping and medium boxes? Does this mean athletes are only using medium effort to execute all these medium jumps? Ah, no, not exactly. Let me talk about how high we jump and box height before I go into programming and various jumping strategies. Then I can draw some lines connecting the various jumping height strategies.

Before I go any further, this article is not about box heights. It’s about medium-level intensities of jumping or plyometric activities. I include boxes because it is a no-brainer strategy if they’re available. I want to make sure, though, that you don’t use the lack of boxes as an excuse to not participate in jumping and plyometric activities.

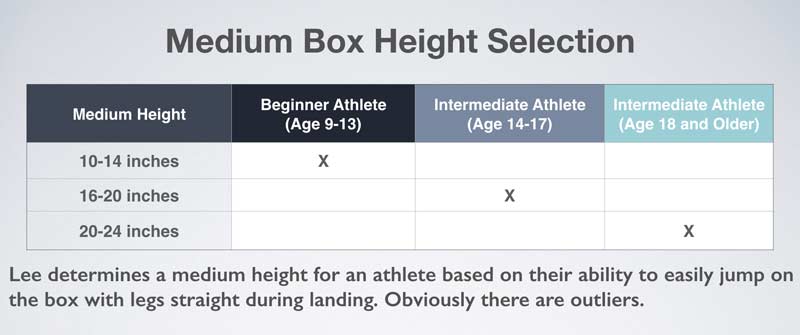

Take a look at the chart below. It outlines what a medium box means to different athletes. Please keep in mind that this is just a chart and not a commandment—it’s a starting point. You can adjust athletes to box height accordingly.

The heights outlined in the chart aren’t extremely high—hence the name medium box. A typical question people have is: How do we challenge our athletes enough to gain improvement if we are not jumping up to a maximum height box? The answer lies in the application of jumping strategies.

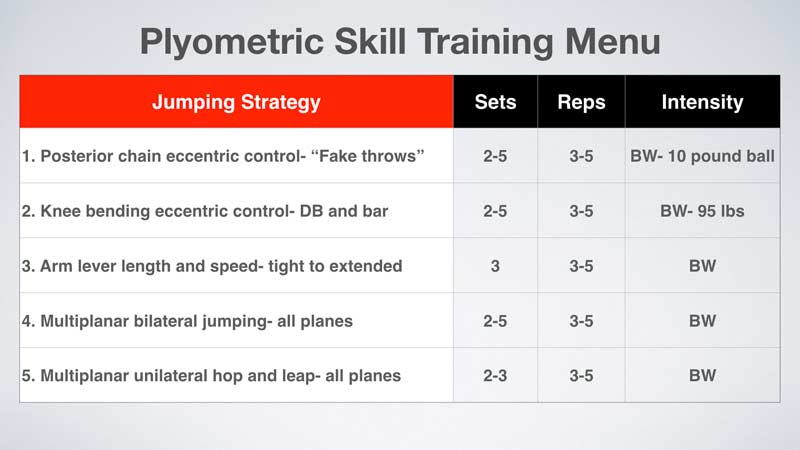

The strategies in the chart below are not just for jumping onto a medium box. They’re additional strategies to build eccentric capacities in the various areas of the body that contribute to jumping better, especially when referring to the reversibility of effort (when you must change the direction down to up quickly).

The chart above might seem elementary. You bet it is! Stop thinking that we have to create the next YouTube sensational drill series. Do things with great intent and purpose, keep them fundamental, add variation, and you’ll have one heck of a strategy to improve your athletes safely. And remember to live for another day and always come up and inch short versus a mile over. Your athletes will thank you.

In the next section, take a look at the video demonstrations of the five jumping strategies listed in the chart. Watching them will help drive home the message of why.

Building Eccentric Control with Fake Throws and Other Exercises

Posterior Chain Eccentric Control with Fake Throws

What are fake throws? They’re part of a strategy I developed decades ago to elicit a fast eccentric action through the kinetic chain. Basically, an athlete moves a light medicine ball very quickly as if throwing it, but suddenly stopping it to create immediate deceleration (you can use other weights as long as they are 4lb-10lbs).

When doing a fake throw, the muscles throughout the body quickly tense to stop all movements, from limbs to upper and lower body. This was my way of creating an innate stiffness in the body to control movement by building eccentric control. There are countless strategies to use the fake throw concept to increase eccentric control.

Video 1. I use a very basic landing skill with a high-to-low vertical fake throw to cause posterior loading overload.

Knee-Bending Eccentric Control with DB and Bar Loading

Athletes doing these exercises use DBs, a bar, or bodyweight to execute the movements. Knee-bending eccentrics are performed with the upper body simply dropping straight down with little to no hip flexion. The weight is delivered primarily to the knee and ankle joints as the primary spring loaders. These kinds of movements cause an important adaptation to higher speed loads. If the athlete quickly redirects the load back up, the movement aids the coordination of agonist and antagonist muscle functioning even though it’s highly focused on tendon resiliency when not going very deep.

Video 2. Knee-bending eccentric control using a dumbbell and a bar for loading.

Arm Lever Length and Speed from Tight to Extended

Arm action may be one of the most overlooked aspects of jumping. Depending on the type of jump, the arms can be kept closer to the body and never extend past 90 degrees at the elbow. Yet, in a sport like volleyball, outside hitters use a very long approach with relatively long ground contact time to execute a high vertical displacement. To achieve this, the athlete swings their arms much longer to coordinate the action of the approach jump footwork (the inside foot touches first followed by the outside foot).

Video 3. In some sports, the arms swing long to coordinate the approach jump footwork. In other sports, the arms stay close to the body to quicken the jump.

A middle blocker in volleyball will keep the arms close and vertical to the body, never getting too far out front until they reach the peak of the jump and attempt to block. This arm action lets them jump quicker to execute a block. A soccer goalie having to jump quickly to punch a ball coming high at the goal will also use a very tight quick arm action to get up quickly to time the speed of the ball.

Multiplanar Bilateral Jumping in All Planes

Video 4. Athletes learn to manage body control by performing jumps in various directions.

In this video, the jumps are performed in various directions. You can challenge an athlete with a lateral jump, a lateral jump with 90 degrees of rotation, a forward jump with transverse rotation at any degree, etc.

The athlete’s ability to effectively manage body control while performing multiplanar jumps is critical in overall athletic preparedness. In sport, athletes often land in awkward positions, and if they’ve never been challenged or experienced this before, their injury risk rises.

Multiplanar Unilateral Hops and Leaps in All Planes

Video 5. Medium intensity single-leg jumping exercises prepare athletes for sports often played on one leg.

Multiplanar hops and leaps follow the basic path as the multiplanar jumps. The obvious hurdle to overcome is making sure athletes are prepared to manage single-leg exercises with great control.

Performing medium intensity single-leg jumping exercises is valuable because sports are so often played on one leg, requiring an athlete to very quickly stabilize in the single-leg landing patterns.

It should be pretty clear that if you’re not addressing the “not so common” strategies to improve the jump, you’re leaving resources untapped.

Do not think I don’t know the fun stuff is what athletes keep coming back for. I totally agree you can have your cake and eat it too. What I mean is, if you want to make sure you do exercises that challenge the athletes and make it fun yet still focus on the appropriate intensities and safety parameters—as Sylvester Stallone says in Rocky, “GO-FOR-IT.”

Body-Only Exercises and Skills

I want to shift gears now to completely address jumping and plyometric type exercises with the use of ZERO equipment. Yep, just bodyweight strategies that can challenge the nervous system to elicit a coordinated response. These exercises bridge the gap between the reactive low box and low-level exercises and the monstrous big box and high hurdle training.

Bodyweight exercises bridge the gap between the reactive low box & low-level exercises and the monstrous big box & high hurdle training, says @leetaft. Share on XHey, wait! It’s a great time to define the difference between jumping and plyometrics. I know this is talked about to death, but I’d feel remiss if I don’t let you know what I think about these two strategies.

When I speak of jumping (leaping and hopping also fall into this category), I’m primarily concerned with the concentric effort of the jump. Meaning, the attention is on pushing through the floor to lift the body off the ground. My attention to how long it takes—I certainly don’t want it slow—isn’t as urgent as it is when focusing on plyometrics. Now, I do realize there will likely be an eccentric or loading phase to the jumping, leaping, or hopping, but the focus isn’t on that aspect of the movement—it’s on pushing up or concentrically driving the body up.

Plyometric exercises, on the other hand, are totally focused on the quick turnaround between landing and jumping. We call this the amortization phase, the loading phase—you know, the phase between going down and going up. We want it quick!

The difference between the jump and the plyo (plyometric) is that the jump relies a lot on the muscular system to provide the energy to jump. The plyo does need help from the muscle for sure, but it’s the tendon and its ability to store and release energy quickly that we want. Are we good?

Now I want to dig into some jumping and plyo strategies, using nothing but the ground and the weight of the body—gravity will jump in there too, so don’t even fight it.

Bodyweight Jump Strategies

To ensure my athletes have a great foundation of medium-intensity jumping, leaping, and hopping, I start with stationary exercises like those in the video below. The video also sets the standard of how to define jumps, leaps, and hops. Remember, these fall under jumps—not plyometrics—so there will be more emphasis on the concentric portion of the movement.

Video 6. To give athletes a great foundation of medium intensity jumps, leaps, and hops, start with these stationary exercises.

But what if I want to put a focus on more posterior dominant versus quad dominant exercises? What could I do? Of course, I’m going to allow the hips to flex forward much more. If my attention is on quad dominant, I won’t allow the hips to flex forward and will attempt to keep the upper body more upright. But this causes me to use more ankle dorsiflexion so I can downwardly load. Take a look at the video below showing examples of a posterior, or hip, dominant jump versus a quad, or knee, dominant jump.

Video 7. Example of a posterior-hip dominant jump vs. a quad-knee dominant jump.

One of the goals of a solid jumping program should be to challenge body and spatial awareness. Body awareness means where the limbs are in space during a movement. Basically, am I in control of hitting proper positions with arms, legs, and entire body? Spatial awareness lets us know where our bodies are in space. Meaning, am I tilting to the right, or leaning backward, or about to fall over? Kind of important to be good at if you want to be a successful jumper and mover.

Bodyweight Plyometric Strategies

In this section, I’ll pull your attention to using plyometric strategies to challenge athletes’ abilities to get off the ground much faster while still moving extremely efficiently—in other words, not sloppy while executing the exercises.

Earlier I discussed posterior versus quad dominant performances while jumping. It’s easy to focus on either/or when jumping. When performing medium-level plyometrics, we start leaning toward quad dominant and lower leg dominant emphasis.

Why? Well, if we’re not jumping from or at maximal heights and don’t need as much hip bending to help absorb forces, we typically can quickly return the energy using more tendinous structures and not require as much power from the muscles—as in a big hip flexion to load the posterior chain.

If my goal is to increase the speed I get back off the ground, I need to limit how low I go when I land. To do this, I rely on more ankle dorsiflexion and knee flexion and less hip flexion. But truthfully, I don’t want a ton of knee flexion either. If I have that, I end up losing the energy in the tendons in the form of heat. It comes down to landing and jumping back up as quickly as possible.

I didn’t mean to skate over an important aspect of stored energy in the tendon. Let me explain what I mean by the tendon losing heat. When an athlete lands and instantly goes back up, the energy built up in the tendon is used to “rebound” the tendon from its stretched state back to its shortened state very fast. This causes an elastic response, which is what makes athletes faster.

But if the athlete lands and pauses, the energy stored in the tendon during the stretch phase can’t hang around for very long. So, the tendon relaxes to the stretched state, and the energy that was built up gets released in the form of heat—meaning no more elastic response or fast movement. Kind of sucks when this happens. There’s more to it, but this gives a birds-eye view of what we want to accomplish with plyos.

Medium Intensity Lower Body Plyometric Exercises

When performing medium-level plyometrics, a coach must have a reason for going sub-maximal yet going higher than the reactive exercises performed with a low box or low-level reactive jumps. My answer to this falls in the realm of learning to manage more load than the very low-level exercises and before the high loads come with the maximal plyometric exercises, such as high load depth jumps.

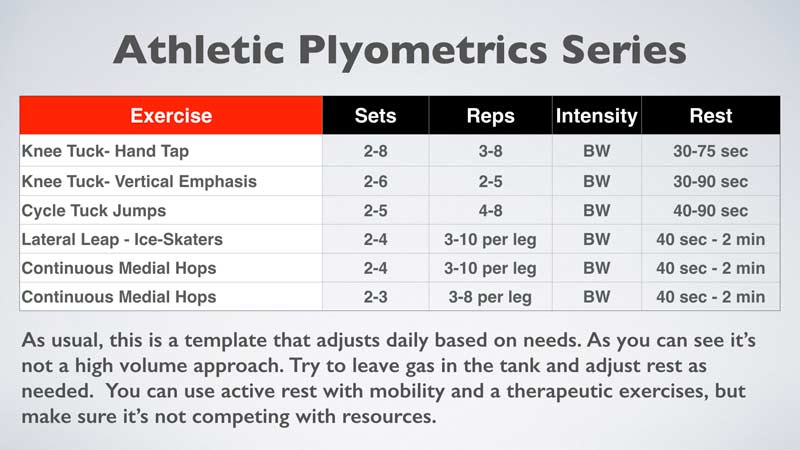

In this section, I want to outline several of my favorite exercises to challenge an athlete’s loading and exploding abilities as well as their coordination to manage variations in patterns.

Think about this for a second. If an athlete wants to move quickly off the ground, they must apply force into the ground much more quickly. They must not only apply force quicker but also redirect the force quicker to leave the ground quickly. Now, low-level plyos do allow quickness off the ground, but there’s not a lot of force applied into the ground—it’s merely elastic energy.

In the early to middle training phases, medium-level plyometrics are the best way to get speed off the ground & force into the ground, says @leetaft. Share on XOn the other hand, if they jump from a maximal height, they will greatly increase the force into the ground but might not be able to get off the ground very quickly, at least not in the early to middle phases of training when they’re not fully prepared. So, the best alternative to get both speed off the ground and force into the ground is medium-level plyometrics.

Here is a list of exercises I love to use. I’ve included videos so you can see the execution of the exercises.

The Knee Tuck Series

Tuck Jump with a Hand Tap on the knees to slightly control the height. To execute this plyo, the athlete must not put too much emphasis on jumping high but rather jumping quickly. You’ll notice the athlete’s head doesn’t go vertical very much, but the knees and hips flex quickly to bring the knees up to the outstretched arms and hands.

Video 8. Tuck jumps with a hand tap emphasize jumping quickly.

Vertical Tuck Jump. In this version of the tuck jump, the athlete attempts to bring the knees up above the waistline to challenge body awareness and to increase the intensity of the landing. In this exercise, you can see the athlete is trying to jump higher by watching the head travel vertically.

Cycle Tuck Jump. The level of body awareness goes way up as well as the intensity of the landing. The athlete is not jumping maximally, as these are medium-level exercises, but the force into the ground is increasing as it slowly goes toward more unilateral bias.

The Lateral Series

Lateral Leap. Also knowns as an ice-skater, the lateral leap challenges the athlete’s ability to use effective and efficient positions to quickly leap right to left while maintaining stability in supportive structures of the foot and ankle complex, knee, hip, and pelvis, and upper body influencers such as shoulder and head. The athlete must quickly redirect the force going angular into the ground and return in the direction they came.

Video 9. Lateral leaps require athletes to quickly redirect the angular force going into the ground and return in the direction they came.

Medial Continuous Hops. In this video, notice how the athlete performs on the same leg moving to the inside (for example, the right leg moving toward the left or vice versa). This exercise places the stressors on the medial structures of the body, such as the groin and adductors, quadratus lumborum and obliques, and structures of the foot, ankle, and lower leg such as posterior tibialis, peroneal, and gastroc-soleus. The hops also challenge the glute medius to support frontal plane pelvic positioning upon landing.

Lateral Continuous Hops. The stress to the body shifts on this exercise to the lateral structures such as glute medius and other supporting structures. I tend to migrate toward the continuous medial hops more than the continuous lateral hops for one primary reason. In court and field sport, athletes do so much cutting and hard change of direction that the IT-band is always under tension due to the hip structures (TFL and glutes) it attaches to. It’s not that I don’t train this exercise—I just monitor it with my athletes. My first priority as a strength coach is to do no harm.

The Bridge Between Beginner and Advanced Training

I don’t know, but I believe medium intensity plyometrics and jumping have their place. As a matter of fact, because I’m traditionally a very low-risk coach, I love medium intensity plyos. I like to find sound strategies where I can increase the variability, and therefore the feedback, the athletes get by training at sub-maximal levels.

I love medium intensity plyos. I can increase variability and get more feedback when athletes train at sub-maximal levels, says @leetaft. Share on XOne of the ways I attack jumping, especially plyos, is by enhancing the parts of the body above the hips to recoil and redirect energy quickly. This is where the fake throw methodologies come into play.

To enhance the performance and safety of all your athletes, you need to train at all levels and intensities with plyos. A medium level is simply a strategic tool that checks a lot of boxes, at least for me. I use them, I get results, and my athletes gain great foot and ankle resilience. Maybe most importantly, my athletes like them and feel great from doing them. And that’s good enough for me!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Lee:

Thank you! Great content as usual.

Best regards,

Brian Robinson

XL Training

http://www.XLTraining.Net