The 2021 track and field season was unlike any other, and because of the restrictions and restructuring caused by COVID-19, I felt like a first-year coach. As with any new situation, there were many circumstances to learn from. I tend to be my biggest critic at the end of the season, and it is hard for me to look outside of areas where I failed:

- I was unable to get our most talented jumper to the starting line.

- I was unable to get our most versatile jumper to the finish line.

- While we were able to get our most improved jumper to the finish line, it was with results that were lower than we had hoped for.

Fortunately, I work with a fantastic coaching staff who would remind me of the aspects that were going well. At the end of the season, our head coach told me he thought I did some of my best coaching ever, and he was probably correct. Of course, I will not forget the areas in which I failed (I carry a momento that I see every day as a reminder), but our delayed and shortened season posed new problems that required me to think differently. On the plus side, I was able to create some solutions to those problems, many of which will be part of what we do moving forward.

Technical Difficulties and Drills

While there is obviously a technical component to all track and field events, in my opinion, the hurdles, jumps, and throws involve another layer. With more than half of the 2020 season being cancelled and then the 2021 season being delayed and shortened, that additional layer became even more complicated. In many ways, track coaches around the country were coaching two classes of freshmen. I’m sure all event areas were feeling this too, but from a jumps coach perspective, it made practice difficult to manage. Our juniors and seniors were light years ahead of the freshman and sophomores, so there was often a canyon between their technical competencies.

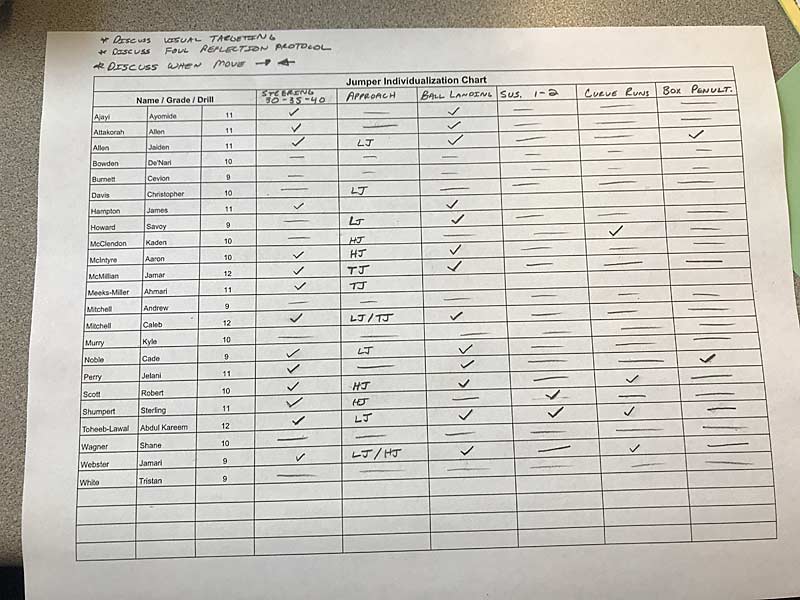

What would be the best way to maximize practice time to address each athlete’s individual needs? The answer—due to our COVID-altered school schedule—ended up being drill work during ‘pre-practice.’ Share on XSo, what would be the best way to maximize practice time to address each athlete’s individual needs? The answer ended up being drill work during “pre-practice.” Due to our COVID-19-altered school schedule, I was able to offer our jumpers opportunities to come to practice 15-30 minutes early, two to three times per week, in order to complete tasks specific to their needs.

Before I go any further, I think it is important to discuss what constitutes a drill. I do not have a formal definition, but what I will offer in this article are activities which:

- Train a physical demand of the event.

- Allow the athlete to feel a movement that is part of the event.

In general, I would say that I am not a “drill guy.” I think the most important technical coaching occurs when the athlete is rehearsing the event. In high jump practice, this would be short or full approach work. In long and triple jump practice, this would be short approach work (4-12 steps; triple may not include all three phases).

If an athlete can make changes in these sessions, I have found the transfer to competition to be more likely. The only drawback in making technical changes within these sessions is that they often take a lot of time, which was something we did not have due to the compressed season length. Complexity was further increased by having a higher percentage of athletes who were competing in the jumps for the first time.

The drills completed during pre-practice were my attempt at accelerating the learning curve of our jumpers. None of the drills used were new. In a normal year, they would have been sprinkled in as needed. With the implementation of pre-practice, the frequency of the drills increased significantly when compared to a normal season.

The drills completed during pre-practice were my attempt at accelerating the learning curve of our jumpers, says @HFJumps. Share on XMost importantly, the drills utilized were specific to each individual athlete. This was based on observing them sprint and jump multiple times prior to assigning the drills that would be their focus. This is probably the most critical part of drill assignment. For example, if an athlete has technical competency in the long jump landing, performing a drill targeting the long jump landing is nothing more than a waste of time and energy, which are our two most precious resources.

Repetition and Variation

When utilizing drills, I try to balance repetition and variation. There needs to be enough repetition so that transfer is made to the event. John Wooden’s Eight Laws of Learning support this: explanation, demonstration, imitation, repetition, repetition, repetition, repetition, repetition. A simple example is the swing leg extension that happens in galloping and run-run-jumps. This motor pattern should be replicated in all three jumps (long jump style dependent), but that does not happen for all athletes. Repping thousands of these during a season/career assists in the transfer of swing leg extension.

Coupled with repetition is variation. If an athlete goes through the motions, learning does not occur. Therefore, whenever a drill is being performed, it is important for an athlete to have one or more of the following:

- A specific movement they are trying to achieve.

- A specific action they are trying to feel.

- A handicap to elicit the desired objective.

- A challenge that makes the objective more difficult.

In the aforementioned run-run-jump example, if an athlete is having difficulty with a rolling penultimate foot contact, I may have them do it barefoot to enhance the sensory component of the drill. If that doesn’t work, I may have them place their hands on their hips to allow them to focus their attention on foot contact. If there is still difficulty, we will slow the drill down as much as possible and then build it back up.

Once they have the rolling penultimate down, I will challenge them to toggle a normal and rolling foot contact between reps or within a rep (within a rep is extremely challenging!). Toggling is helpful because it is required if the athlete does both long and triple jump or high and triple jump. Without further ado, let’s get to the drills that formed our 2021 pre-practice!

Infinity Locomotion

I first heard of the Infinity Walk through Coach Dan Fichter at a Track-Football Consortium. I refer to it as “infinity locomotion” because of the various movements I use (walking, skipping, crawling, etc.) It is a method created by Dr. Deborah Sunbeck, and she explains it in her book Infinity Walk, Book 1: The Physical Self. An introductory video for the method can be found here. I strongly advise watching this prior to reading and watching my example video below. Here are some of the reasons for using infinity locomotion:

- Complete Eye Movement – By completing infinity locomotion in both directions, while keeping focus on a stationary or moving target, the athlete is more likely to go through a full range of eye movement. What makes the figure eight path unique is its combination of movement in the sagittal and frontal planes. There would be less stimulus if only moving forward and backward or left and right because only one plane would be addressed at a time.

- Neural Priming – The figure eight pattern of infinity walking and the additional challenges that can be implemented provide “multiple sensory and motor sources of neural priming which are needed to learn.”1 In simple terms, the Infinity Walk wakes up the brain and gets it ready to learn. Seems like a no-brainer (pun intended) to use in any academic or athletic setting where skills will be taught!

- Vestibular Ocular Reflex (VOR) Stimulus – If you were to stare at an object and then move to the left while maintaining your gaze on the object, your eyes would move to the right. This is the VOR in action. The vestibular system is responsible for regulating eye, neck, spinal, and limb movements to maintain gaze.2

-

- I have seen Fichter speak many times, and one consistent message he has in his presentations is that the eyes are the most under-trained part of the body.

- is a topic I often discuss when it comes to the jump approaches, and it is often an issue with novice jumpers (particularly with those who had minimal exposure to ball sports growing up). Infinity locomotion checks a box for vision training.

- Vestibular Stimulus as a Global Extensor – “The vestibular system is a major source of excitatory influence to extensor or antigravity muscles, particularly in axial or proximal limb muscles, and of reciprocal inhibition to certain flexor muscles.”3 Once again, the figure 8 pattern and visual focus pose a challenge to the vestibular system, which will wake up the extensors, so the participant remains upright. In a normal school year, students sit at a desk for about six hours each day. Sitting has a strong bias for being in a state of flexion, as does “cell phone posture,” so it makes sense to excite those extensors prior to athletic activity!

Video 1. Here, two athletes perform an infinity skip. The water bag, bungee, and arm movements all challenge balance and coordination. The options for variation are only limited by a coach’s creativity. For additional information and examples, see Cal Dietz’s “The Goat Performance Drill” part 1 and part 2 on YouTube.

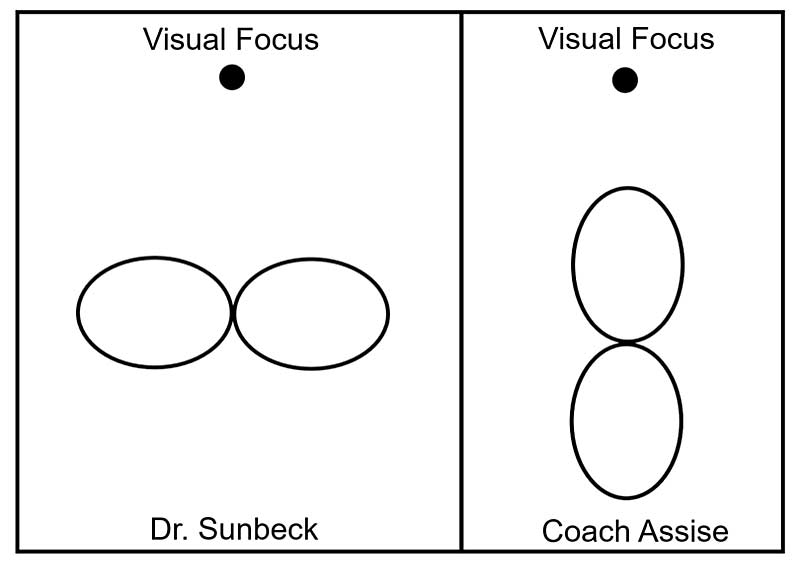

If you watch Dr. Sunbeck’s video, you will notice the figure 8 oriented more side-to-side versus the examples of Homewood-Flossmoor jumpers, whose figure 8 was biased forward and backward.

My reasoning behind altering the drill was that I found it to be more specific to the demands of the long jump and triple jump. By rotating the figure 8, the drill involved a higher degree of convergence and divergence for the eyes. Convergence is especially important in the horizontal jump approach because the target (the board) continually gets closer (until the jumper loses sight of it). Most of the time, I placed a small cone on the ground for the jumpers to focus on (this was the case in the video), doing so to be consistent with the jump board being located on the ground.

By rotating the figure 8, the infinity locomotion drill involved a higher degree of convergence and divergence for the eyes, says @HFJumps. Share on XAs athletes moved closer to the visual focal object, I encouraged them to keep their head level (neutral neck) and track their eyes down to the visual target. There were times we altered the visual focus point or even made it mobile. We also did Dr. Sunbeck’s variation periodically. (Upon reflection, high jumpers will probably do a 50/50 split in the future, due to the nature of the approach.)

It is important to note that I have no idea if my variation takes away from any of the aforementioned benefits of the traditional Infinity Walk. I felt my rationale was solid for the change, and athlete feedback was positive, so I went with it. This was the one drill completed by every jumper who was present for pre-practice.

Ball Landing

Sometimes the universe aligns itself and makes it possible for people like me to make some minor discoveries. At the start of our season, we were indoors due to weather conditions and had to find space to practice away from our indoor track. We ended up in what I think is our cheerleading room. In that room, there were at least 25 exercise balls. I just remember thinking “That’s a lot of balls.”

Fast forward two days. We were back outside, and I had athletes completing a variation of a chair landing drill on the high jump mat because our sandpit was water-logged. An athlete made the comment that he was not a fan of the drill on the high jump mat because it was possible for the chair to tip over and hit him in the head. A second athlete immediately commented “There has to be something else we could use.” I agreed and told them I would think about it.

Later that night, I fell asleep, and in my dream, I saw the exercise balls in the cheerleading room. The next morning, I ordered three exercise balls to be used for the drill. I did not notice any major difference in utilizing the ball versus the chair, and a perk of the ball was it “softened” the landing, which allowed us to be able to perform the drill on FieldTurf. This made it easier for me to keep an eye on all athletes during pre-practice because our horizontal jump area is located outside of our track stadium.

Video 2. The progression in the “chair landing drill” link above can be followed for this drill. The timing of flexing the knees when the feet hit the sand and having the butt replace the heels can only be replicated during a jump, but the movement itself can be rehearsed with this drill.

It is important to note that this drill IS NOT a cure-all for landing issues. Many athletes are not in position to execute a quality landing due to what has happened prior to landing time. Common issues are poor flight angle and over-rotation, which are products of poor hip displacement and poor posture at take-off, respectively. Posture and hip displacement are big rock issues, and if they are a limiting factor, coaches should be sure athlete’s training programs prioritize their improvement.

Run-Run-Jumps

I mentioned some of the variations and benefits of run-run-jumps (RRJs) earlier in the article, and if I had to pick a favorite jump drill, I would have to say RRJs take the prize. I love gallops, skips, and bounds, but RRJs are unique with the inclusion of a true penultimate step. The numerous combinations of foot contact and arm action create a substantial amount of variation, which is a fantastic coordination challenge. Normally, we reach a solid degree of competency over the course of the first two weeks of the season and include them in our warm-ups and workouts two to three times a week for the remainder of the year.

If I had to pick a favorite jump drill, run-run-jumps take the prize. I love gallops, skips, and bounds, but RRJs are unique with the inclusion of a true penultimate step, says @HFJumps. Share on XWith a compressed timeline, we had less time to spend on RRJs on the front end, and I had some athletes really struggling with the coordination and rhythm of the drill. Pre-practice reps were extremely helpful in getting them up to speed with the rest of the group, which enhanced their confidence.

Video 3. Here is a variation of run-run-jumps, which would be utilized for the horizontal jumps. Additional variations and explanations of RRJs, galloping, and skipping can be found via this resource.

Serpentine Runs

I have advocated for the use of curvilinear sprinting and running in many pieces (here, here, here, here, and here). Clearly, I think it is kind of a big deal for all—it simply creates athletes who are more robust. While most of the information I have put out has dealt with curvilinear sprinting, there is definitely a place for submaximal curvilinear work.

I do like curve runs (think of running around a soccer circle) because it allows athletes to feel outward foot pressure, a key in the high jump approach; however, I have begun to prefer runs that follow a serpentine path (also called wave runs or slaloms). The reason for this is it provides athletes with the opportunity to continually exit and enter the curve. This is important because it gives athletes the chance to practice getting into a full body lean (straight line from ankle to head). Too often, athletes feel they are leaning properly, but they are actually bent laterally at the waist and/or neck—not an ideal way to transmit force!

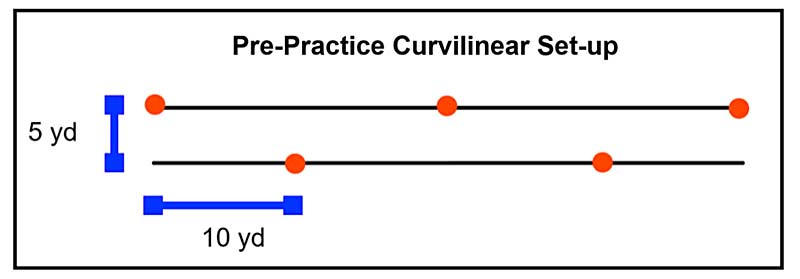

I have begun to prefer runs that follow a serpentine path (also called wave runs or slaloms) because they give athletes the opportunity to continually exit and enter the curve, says @HFJumps. Share on XThe amplitude and wavelength for the runs can be altered. Since this is a pre-practice activity, the intensity of the runs was relatively low, which can be controlled by a relatively large amplitude and wavelength. We tended to set the course with cones on our infield, with a “vertical” distance from crest to trough of 5 yards (amplitude 2.5 yards) and a “horizontal” distance of 10 yards (wavelength 20 yards).

Video 4. A simple submaximal serpentine run.

Besides looking for a full body lean, another factor I like to see is big ranges of motion with the arms and legs. (Note: This was addressed with the athlete in video 4.) I typically spend most of my time cueing athletes to drive their arms down to get the hands to clear their glutes (the hand movement should end behind the glute, creating a window of daylight between hand and glute).

This motion is admittedly biased toward high jumpers, as it will be present in their approach, but it allows for a more fluid run for all because small ranges of motion tend to create sharp corners instead of a rounded path. Yes, I think it is imperative for all jumpers to complete curvilinear work!

Antepenultimate Box

Over the years, I would say that I have had a higher percentage of jumpers who had too large of a takeoff angle during long jump than too low. It seems to be more common for many athletes to block at the board, achieving minimal hip displacement and leading to too high of an exit from the ground and too steep of an entrance back in during landing.

This may have been unique to the population I coach, but this past year I had the exact opposite: five long jumpers, four of whom were new to the event, were classic line-drive flight cases. Normally, I try to work through this during short approach work and full approach rehearsal, but once again, due to compressed time, I tried to speed up progression through the regular use of a drill. The antepenultimate (third-to-last step) box drill is one I have sprinkled in during past seasons for those with too low of a takeoff angle.

In order for a long jumper to attain proper jump height, they must decrease the height of their center of mass prior to takeoff. Usually, attaining a rolling or heel-toe contact during the penultimate step will lead to the required jump angle. Some jumpers, however, need an additional stimulus to get a feel for the center of mass lowering, and this drill gives that sensation.

Although it’s impossible to say, I feel as if the antepenultimate box drill may have led to the most notable changes in those long jumpers assigned to perform it, says @HFJumps. Share on XAlthough it is impossible to say, I feel as if this drill may have led to the most notable changes in those who were assigned to perform it. All five improved one meter or more from the season’s start to its finish, and their changes in flight pattern could have been identified by anyone who was paying minimal attention.

Video 5. While this jumper probably exaggerates the takeoff angle beyond what it needs to be during this drill, I was okay with it because it balanced out when we went to complete jumps on the runway. I suggest a box height between 2 and 4 inches.

Drills Discussed in Previous Pieces

There are additional drills that I have covered in previous pieces, so instead of going into detail on them again, they are linked here for your convenience.

- Curve Initiation and Curve Drills – All videos in the article except #4. These have a bias toward high jumpers, but there is certainly value in many of them for all.

- Low Lunge Walks – I love this drill because you can tell so much about an athlete’s gait without having them sprint.

- Suspended 1-2 – See video #4. This is mainly for triple jumpers, but the hip displacement piece and swing leg extension can be utilized for long jumpers as well.

Moving Forward

Our normal practice start time is 3:30 p.m. One item I am going to propose to our coaching staff is moving the start time back to 3:45, so all athletes (not just jumpers) can partake in their own pre-practice.

I think that our coaches giving our athletes specific items related to their needs (which we already do), with the addition of time to address them, has the potential to reap significant rewards. A second installment of this series will showcase our most improved long jumper and how we devised his specific pre-practice routine.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Sunbeck, D. Infinity Walk.

2. Keshner, E.A. and Peterson, B.W. “Mechanisms controlling human head stabilization. I. Head-neck dynamics during random rotations in the horizontal plane.” Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:2293-2301.

3. Markham, C.H. “Vestibular control of muscle tone and posture.” Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 1987;14:493-496.