In order to graduate with a degree in exercise science, The University of Scranton requires students to complete an internship in a desired career path. This requirement led me to research and apply for internships in both the collegiate strength and conditioning field and the private sector. After filling out questionnaires, shooting exercise demonstration videos, and interviewing over the phone, I was fortunate enough to be selected to spend this past summer as a strength and conditioning intern under Coach Sal Alosi of the University of Connecticut (UConn) Men’s Basketball Program.

Students and graduates typically undertake Internships to gain relevant skills and experience in a particular field. While these were influential in my choice to intern at UConn, my primary motivation was being able to study under and be mentored by Coach Alosi, who has coached at both the professional and collegiate levels, and who was spoken of very highly by a professor of mine at The University of Scranton.

While there are numerous experiences and lessons that I learned in those three months, I decided to highlight three that I believe will benefit other young coaches attempting to break into the strength and conditioning field.

Lesson 1: Experience Triumphs Over Knowledge

Like most 21-year-olds would, I entered this internship thinking I knew more than I did. Having completed three-quarters of my undergraduate degree in biochemistry and exercise science, I would say the amount of knowledge I had obtained was fair—I understood basic strength and conditioning concepts after having read a ton of Mike Boyle’s stuff, I’d watched a few of Glenn Pendlay’s videos, and I had over a 3.70 overall GPA to show for it (humble brag). My thoughts quickly changed during the first couple weeks of my internship, as it was the first time I was actually in a weight room and able to work with athletes as a “coach.”

I entered this internship thinking I knew more than I did. That quickly changed during the first two weeks when I was able to work with athletes as a “coach,” says @blakehammert. Share on XWords and pictures do not do UConn’s weight room justice—it is something iron enthusiasts need to see and experience for themselves. It is heaven: grey turf running down the center of the weight room with UCONN written in white and red letters, Eleiko barbells and bumper plates, Watson dumbbells ranging from five kilograms to 50 kilograms, glute ham raises, reverse hyperextensions, kettlebells, maces, clubs…you name it, this weight room has it. While I stood there in awe of the weight room, I was equally amazed by every athlete who walked into the weight room towering at least 6 inches above me.

I was not necessarily coaching every single athlete, but there were times when I instructed athletes in warm-ups and cooldowns and had to cue athletes on specific movements. It is one thing to know how a book describes and teaches the Romanian deadlift—“A hip-hinging pattern that emphasizes the hamstrings and glute maximus… set core, slight bend in the knee, push hips back, keep the bar close to your leg, go to mid-shin level, etc.”—just as it is one thing to be able to memorize concepts, such as that a 10-rep maximum is roughly 75% of your one rep maximum. It is a whole different ball game, however, when an athlete does not understand what you thought was such a basic task in asking them to perform a Romanian deadlift, and now you have to figure out additional cues to give him.

Using a cue like “It’s a hip-hinging pattern” or “Don’t bend your knee and turn the RDL into a squatting pattern” does not necessarily work well with an athlete who has spent limited time in a weight room. Rather, my choice to use the cue “Try to get your hips to touch the wall behind you” was easier for athletes to understand and did a better job.

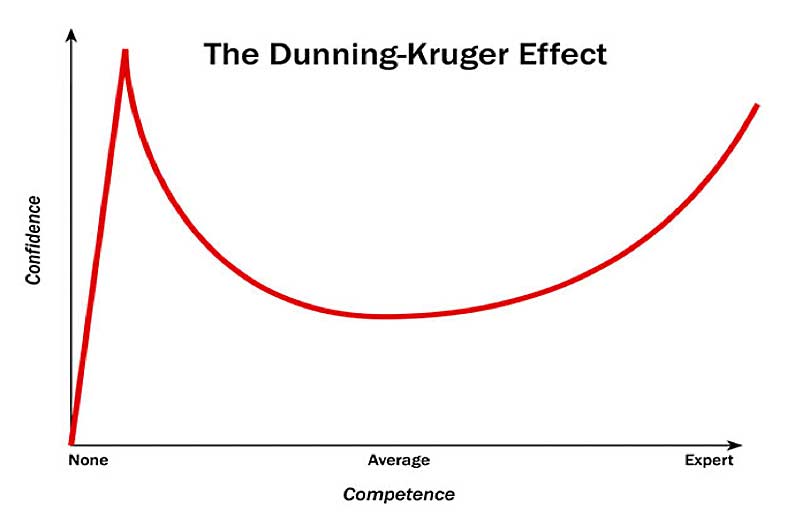

During this experience, if you are familiar with the Dunning-Kruger Effect, I was essentially a living version of it (see figure 1).

I would not consider myself to have gone through a full cycle of the Dunning-Kruger Effect over the duration of my internship—although I learned a great amount over the three months, I am still far from an “expert” and probably have an additional 15-20 years of coaching before I begin my second ascent. More or less, I learned to stay levelheaded. I am also not knocking getting education or self-educating yourself, as I believe investing in yourself over the long haul will prove to be beneficial. What I am saying, and what I wish someone had told me, is to go coach.

It does not have to be at a big Division I program; it can be with local high school athletes. Go somewhere based on the coach(es) there; where you can learn, gain experience, and be mentored. Sure, a Power Five school with a well-known logo looks great on a resumé, but if your main job is picking up weights, cones, and cleaning, how beneficial is it to you as a coach?

For your internship, go somewhere based on the coach(es) there; where you can learn, gain experience, and be mentored. Share on XKnowledge can be understood as guidelines. You should use the guidelines provided in textbooks just as they sound—as guides. A great coach takes these guidelines and can alter them based on an athlete’s needs, using the “eye of the coach.” The only way to develop an “eye” is to get experience coaching. Prior to this internship, I would have done everything by the guidelines and never strayed. Being able to attend weekly strength and conditioning staff meetings, ask questions regarding athlete’s programming, and be present in strength and conditioning sessions allowed me to gain both knowledge and experience as a coach.

At the end of the day, a coach who has a base of knowledge, can draw from multiple experiences, and has been mentored by a great coach will be more well-rounded than a coach who simply picked up equipment for three months.

Lesson 2: There’s More Than One Way to Skin a Cat

Go on Twitter or Instagram and you will see coaches pushing their philosophies and reasoning as to why their program is superior to other programs. A program can be rooted in (variations of) Olympic weightlifting, the Conjugate Method, or even jumps and medicine ball throws. While I would tend to say one is better than the other, that is not the point of this article, and I am sure if I looked hard enough, I could find teams that have won championships using all three of these methods.

Some coaches have athletes execute lateral box hops with the front foot performing the hop versus the back foot. Is one superior to the other? Tough to say—I would ask what the goal of the exercise is. If you are programming the exercise to develop lateral agility or lateral power using Chris Doyle’s PAL mechanics, you would program an athlete to jump off their back leg. “P” stands for “Push to move”—an athlete is stronger pushing (using their back leg) than they are pulling (using their front leg). A statement that came up in a strength and conditioning staff meeting is particularly relevant in this scenario: “The only exercise that is inherently bad is one programmed without a purpose.”

I entered my internship with the belief that all athletes should perform a bilateral squatting pattern of some sort, as they will have the ability to maximize the load used. But what happens if an athlete cannot necessarily squat bilaterally due to structural imbalances? Do you force them to squat bilaterally, increase their risk of injury, and ultimately not let them progress in the weight room? Or, do you alter their program slightly and have them perform unilateral squatting patterns?

This experience occurred with an athlete this past summer. The choice was simple: Rather than spend two to three of his four years trying to fix a structural imbalance that most likely will not be fixed, we could have him perform unilateral squatting patterns and let him progress on them and get stronger. That is not to say athletes did not squat bilaterally—all (but one) did, to proper depth, and extremely well. This was just one specific circumstance.

In the sport of basketball, an athlete may be big enough for their position. So, does the coach continue to program this athlete in a similar manner to the other athletes? Or does the coach alter this athlete’s program to increase other athletic qualities such as explosive strength, elastic/reactive strength, or speed? The choice should be, yet again, simple—do not use one program for every single athlete. It’s a disservice to the athlete. Look at their specific needs and training age and go from there.

All in all, there is no “one-size-fits-all” method for getting athletes stronger and increasing athletic performance. Nor is any program inherently bad. A program that is well-thought-out and created with a purpose, is adaptable to the needs of an athlete, and is coached with intent will provide athletes with far more benefits than a program that was blindly created for them.

Lesson 3: Read, Read, and Read

Prior to my internship, unless it was a textbook for school, I did not read. You can imagine my thoughts upon seeing an internship curriculum that required me to read and summarize eight books and eight articles, as well as numerous videos. Nonetheless, I got through them and am glad I did. I think a quote by Coach Johnny Parker sums this lesson up well—“Ordinary people have big TVs; extraordinary people have big libraries.”

To be extraordinary, you have to want to learn and grow. One simple method of doing so is through the self-education process of reading. The books do not necessarily have to be strength and conditioning based, they can be books about leadership, culture building, and even how to stop procrastinating. The more a person pushes themselves to grow, the more they will achieve. Essentially, being “forced” to read tested my work ethic and discipline, helping me grow as an individual and coach.

Essentially, being “forced” to read tested my work ethic and discipline, helping me grow as an individual and coach,” says @blakehammert. Share on XOne of the books I read over the summer that I highly recommend is Extreme Ownership: How U.S. Navy SEALs Lead and Win by Jocko Willink and Leif Babin. While this book is not necessarily strength and-conditioning based, it will both make you want to become a Navy SEAL and provide you with lessons that you can apply to the field of strength and conditioning.

One detail that I found very interesting regarding Extreme Ownership was the idea that leaders do not take credit for their team’s success. Rather, they give credit where it’s due—to the subordinates of the group. This can be exhibited in the strength and conditioning world very easily: A coach should not take credit for and/or brag about the success of their program; rather, they should give credit where it’s due, to the athletes who trust in the program and give 100% inside and outside of the weight room (including sleeping, eating, warm-up/cooldown, etc.). This is extremely important, as it can help develop a team’s culture at every level, creating a high-performance, winning team.

While it is important for leaders to give credit where it is due, in my opinion, it is equally, if not more important, for them to set the standards. A leader’s attitude will set the tone and either drive performance or make it crash. The key to “driving” (and not crashing) performance lies in what a leader tolerates. In essence, the only part of a “bad team” that is “bad” is its leader.

During the internship, an assistant coach’s remark to a player about wearing compression pants with holes one Saturday was, “How you do one thing is how you do everything.” While the coach was joking (I think), this quote hits the heart of what a leader’s attitude should be—one of intent. Do the small things right, and over time they will add up and lead to success.

If a coach stresses that athletes properly warm up, eat, hydrate, sleep, and perform every lift as if it is the most important rep of the block, they set a tone that will drive performance. Leaders need to push the standards and let others follow. Additionally, coaches must establish consequences in preparation for substandard performances; otherwise, these poor performances will become the new standard—the “norm.”

Leaders must believe in the mission, the bigger picture. By doing so, they do what is best for the team. Likewise, the subordinates must understand why the leader requires them to do this. Examples can be seen in athletes understanding why they perform Olympic Lifts (they are explosive, ground-based movements that require 100% motor unit recruitment and eccentric strength to finish) or why they are required to strength train (increase athletic performance/ decrease risk of injury). There should be a purpose behind everything a leader does. By telling subordinates (athletes) the why, leaders build their subordinates’ trust and belief.

My Three Internship Takeaways

In summary, from my internship with Coach Alosi, the three lessons I learned and benefited from the most were:

- Go get experience coaching by—you guessed it—coaching.

- Program with a purpose, coach to the best of your ability, and do not be close-minded to other programs.

- Read and never stop self-educating.

I was fortunate enough to be mentored by a coach who I believe is one of the best, not only in Division I basketball, but in collegiate athletics as a whole. Additionally, being able to work with and help a program with a top-notch work ethic and culture, even in very small ways, was an experience I will never forget. Furthermore, my desire to work in the collegiate strength and conditioning field has never been greater, and I look forward to applying these lessons I learned day-in and day-out wherever I find myself coaching in the future.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF