MMA (mixed martial arts) is a sport that has grown exponentially across the globe. Organizations such as the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), Bellator Fighting Championship, and One Fighting Championship (ONE FC) organize events on an almost weekly basis, offering viewers battles between the most highly skilled MMA athletes in the world. The growth of combat sports has made athletes more competitive and skilled than ever—consequently, effective strength and conditioning tactics are an even more important piece of the puzzle for a successful outcome.

Fighters must develop a robust level of metabolic conditioning, strength, power, and speed to complement their skill, so that as time wears on, they can remain sharp and focused. Share on XThe fighter will always have two primary opponents upon entering the cage: the fighter standing across from them and their own preparedness. Fighters must develop a robust level of metabolic conditioning, strength, power, and speed to complement their skill, so that as time wears on, they can remain sharp and focused. Due to the complexity and many physical demands of MMA, as well as the challenges of organizing training, I have had to meticulously structure my programs to meet these various demands when training my combat sport athletes.

Energy Systems

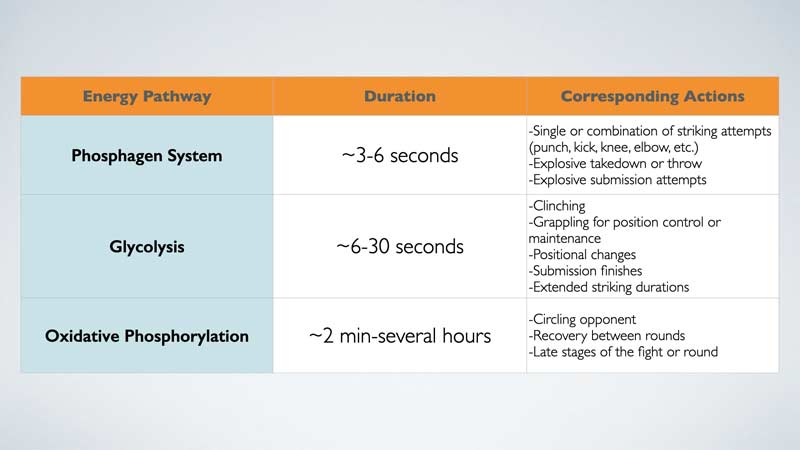

When analyzing the physical demands of MMA, it can be overwhelming to even begin thinking about developing a program. Athletes require high levels of metabolic conditioning, the ability to rapidly generate explosive knockout power, the strength to take down and control an opponent on the ground, and everything in between. Each of these skills relies heavily on different energy system pathways, some of which directly compete with one another in terms of training, which makes matters extremely complex. Figure 1 below demonstrates actions seen in a typical MMA bout, as well as the corresponding energy system they utilize.

The style, size, and matchup a fighter has will ultimately determine what blend of these movements takes place in a fight. Some fighters specialize in grappling-based arts (e.g., Brazilian jiu-jitsu, wrestling, Greco-Roman, etc.) or striking (e.g., boxing, Muay-Thai, taekwondo, etc.), while others possess a somewhat even blend of them all. According to the UFC, as of 2018, heavyweights had the highest occurrence of fights finished by knockout (KO/TKO) at 60.1%, whereas women’s strawweight contenders had both the highest percentage of submission finishes at 27.1% and the highest percentage of decision bouts at 65.9%. This only adds to the list of considerations we must contemplate when designing a program.

This is similar to a sport like American football, where coaches cannot simply train skill position athletes (wide receivers, running back, etc.) as they would an offensive or defensive lineman due to the discrepancy in the playing style. Even though it’s the same game—or in terms of fighting, the same sport—there are very different performance strategies.

Metabolic Conditioning

MMA bouts are formatted as either three five-minute rounds for a standard match or five five-minute rounds for championship and main event bouts. Fighters must possess enough stamina to recover quickly between rounds, as well as maintain a high level of intensity throughout each round to ensure the best possible chance of winning. As previously mentioned, some fights end in the very early stages of competition—whether it be by knockout, submission, or injury—but for those who go the entire distance, it is advantageous for a fighter to possess robust levels of metabolic conditioning.

For those who go the entire distance, it is advantageous for a fighter to possess robust levels of metabolic conditioning, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on XTraditionally, many coaches would prescribe long, slow, steady-state aerobic activity for their fighters to build aerobic endurance. These activities included things such as jogging, biking, and swimming for multiple hours a week at or near ~40%-70% max heart rate. This would build the foundation for the fighter, who would then build further from there and eventually train in a more specific manner as the fight neared.

While this method may still have merit in some instances, coaches have instead begun to introduce their fighters to high-intensity interval training (HIIT) to produce similar, and in some cases superior, results in a shorter period of time. This type of training involves brief bouts of intense exercise (approximately >90% VO2 peak) interspersed with often longer bouts of lower-intensity recovery. The major benefits of HIIT over low-intensity steady-state conditioning (LISS) appear to be that adaptations are achieved in a shorter amount of time, and negative interactions between strength and power development are less likely to happen when training concurrently.1,2

A HIIT session can be formatted in many ways, and it certainly cannot go without being said that fighters get a great deal of this conditioning in their skill sessions. Depending on how specific a coach would like to get, they may format a general HIIT session as something like 30 seconds of running on an incline treadmill followed by two minutes of walking and active recovery.

I may have the fighter do one minute of striking combinations, followed by one minute of takedown defense and sprawling, followed by 1-5 minutes of active or passive recovery.1 Another popular option is to set up a series of resistance exercises (also known as circuit training) and have a fighter execute each one back-to-back with little to no rest for upward of 2-3 minutes.1 The options are seemingly limitless, and it is in this area that art meets science, allowing coaches the artistic freedom to craft a session built uniquely for their fighter. Important considerations the coach can manipulate are:

- The rest period.

- Mode of exercise.

- Volume.

- Duration.

Strength and Power

Strength and power are critical components that contribute to the success of MMA fighters. Strength underpins power, and power is often associated with explosiveness, which is of utmost importance for throwing punches, kicks, elbows, knees, etc.1 Furthermore, the ability to sustain such power across a fight is critical—thus, training a fighter’s power endurance or ability to resist fatigue and sustain power output is of utmost importance.

The major issue that I run into when structuring a plan for combat sport athletes, particularly when seeking to increase power, is where, when, and how often to train for it, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on XThe major issue that I run into when structuring a plan for combat sport athletes, particularly when seeking to increase power, is where, when, and how often to train for it. It is commonly accepted that power will suffer at the expense of increasing cardiovascular endurance, but gains can still be made. Intelligent programming can help mitigate the negative consequences.

Research suggests that gains in power and maximum strength can be made using a daily undulating model similar to that of a classic strength-power periodization model (where multiple weeks are dedicated to strength endurance, and then power training, sequentially) which could allow for the development of multiple training aspects at once.1,3 It is possible that one day a week of power training could help to sustain or even build power for a fighter, while allowing for the training of many other physiological qualities simultaneously.

When designing a workout intended to increase power, emphasis must be placed on rapidly moving the weight through the concentric portion of the lift and keeping resistance between 40% and 80% of the athlete’s 1RM for each given exercise.1,4 Exercises may vary on their optimal load depending on whether they are upper body or lower body, pushing, pulling, hinging, jumping, or a host of other factors; therefore, coaches must do their own research to discover proper loading schemes for their athletes.

One last important consideration when seeking to improve strength and power in fighters is the specific development of isometric strength. Many of a fighter’s grappling and clinching scenarios involve gripping, squeezing, and holding their opponent in order to maintain or improve position, work through a takedown, or finish a submission. This is where coaches must again get creative in their training techniques by implementing exercises such as weighted carries, holding or squeezing medicine balls and sandbags, or even dead hangs from a bar, to name a few. Bounty et al.1 even suggest using towels for pull-ups, rows, and hangs to further tax the grip strength of fighters and provide a novel stimulus.

Speed

Speed is a critical component in MMA, as fighters must be able to rapidly generate strikes, evade their opponents, and close distances as quickly as possible. Speed is often trained and displayed in sparring and technical skill sessions, but trainers can also help to develop it through several other training methods. Plyometric training—specifically unloaded drop jumps and hurdle jumps—has been shown by Gomez et al.7 to increase kicking power in football players when combined with resistance training. One could extrapolate this information and potentially reproduce similar results with fighters whom they train and perhaps even build from it, using both upper and lower body plyometrics to increase kicking and punching power.

Ballistic methods such as weighted jump squats have also been shown to improve movement speed6 when loads were used at ~30% 1RM. As previously discussed in the power development section, selecting the proper load for executing these movements is of utmost importance to yield optimal results. Speed is a rather delicate physiological quality to train, particularly when looking at the fine motor skill involved in movements such as a punch, kick, knee, or elbow. Attempting to load these movements without a firm understanding of the cause-and-effect relationship should be avoided.

Putting It Together

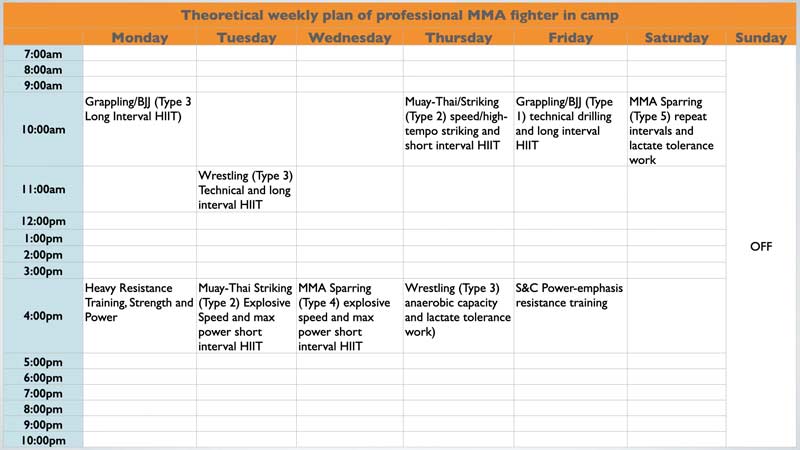

The most difficult part of training an MMA fighter is not the training itself, but rather the organization of all the training components combined. The best resource I have come across to help do so is the book Science and Application of High Intensity Interval Training, by Martin Buchheit and Paul Laursen,5 specifically the chapter that Dr. Duncan French contributes to discuss exactly how this can be done. Below is an adapted table from the book:

To better understand this outline, once must understand what each “type” of HIIT targets. As such, each is described below:

- Type 1: Aerobic Oxidative

- Type 2: Aerobic Oxidative + Neuromuscular

- Type 3: Aerobic Oxidative + Anaerobic Glycolytic

- Type 4: Aerobic Oxidative + Anaerobic Glycolytic + Neuromuscular

- Type 5: Anaerobic Glycolytic + Neuromuscular

Each of these training types are further detailed in the book, with information about work-to-rest ratios, volume, mode of exercise, and much more. As you can see, the skill sessions (e.g., wrestling, striking, etc.) provide the majority of what one may classically define as conditioning.

The most difficult part of training an MMA fighter is not the training itself, but rather the organization of all the training components combined, says @jimmypritchard_. Share on XThis type of programming requires sound communication between the strength and conditioning coach and specific skill coaches for each discipline, as they can work together to provide the targeted stimulus within each session. It is easy to see where a lack of communication can quickly result in overtraining, as a striking coach and grappling coach may cross over with back-to-back type 5 sessions on the same day (or something similar) and create unwanted, excessive fatigue in the fighter. Most high-level fighters now have a primary coach who helps to organize all of the training and communication between parties; therefore, it is important that a strength and conditioning coach plays a major role in the planning.

In order to successfully develop a plan for an MMA fighter, I always target each of the factors previously mentioned to some degree. Every aspect of the program will then be tailored to the fighter depending on their own individual strengths and weaknesses, as well as who their opponent is and how much time is available before competition. I view every program much like a stone that I must sculpt; who it is I am training will determine how it looks in the end.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Bounty P.L., Campbell, B.I. Galvan E., Cooke M., and Antonio J. “Strength and Conditioning Considerations for Mixed Martial Arts.” Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2011;33:56-67.

2. Gibala M.J. and McGee S.L. “Metabolic adaptations to short-term high-intensity interval training: a little pain for a lot of gain?” Exercise and Sports Sciences Review. 2008;36:58-63.

3. Hartmann H., Bob A., Wirth K., and Schmidtbleicher D. “Effects of different periodization models on rate of force development and power ability of the upper extremity.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2009;23:1921-1932.

4. Kilduff L.P., Bevan H., Owen N., et al. “Optimal loading for peak power output during the hang power clean in professional rugby players.” International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2007;2:260-269.

5. Laursen P. and Buchheit M (Eds). Science and Application of High-intensity Interval Training. Human Kinetics: 2019.

6. McBride J.M., Triplett-McBride T., Davie A., and Newton, R.U. “The effect of heavy- vs. light-load jump squats on the development of strength, power, and speed.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2002;16:75-82.

7. Perez-Gomez J., Olmedillas H., Delgado-Guerra S., et al. “Effects of weight lifting training combined with plyometric exercises on physical fitness, body composition, and knee extension velocity during kicking in football.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 2008;33:501-510.