I recently posted an article examining my reservations and growing reluctance on using static loading with my athletes, so naturally I wanted to follow that up with a practical and detailed look at how and why I utilize band loading. If you’ve followed me on social media the last few years, you know my affinity for bands is hardly a secret. Over time, what began out of honest demand (as well as the necessity to find ways to load my athletes while circumventing injuries), has evolved into more consistent applications, of which there are many. Through the years, I’ve found that, if nothing else, resistance bands are extremely versatile and can be tremendous resources in training, irrespective of the athlete’s health or abilities.

Despite the goofy stuff we see circulating on social media, I would encourage you to keep an open mind to the incredible versatility of resistance bands, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XThe propensity for global misuse and misappropriation of band training has, unfortunately, given the method a bad reputation, making it inadvertently perceived as something only for social media clout or attention grabbing. But despite the goofy stuff we see circulating on social media, I would encourage you to keep an open mind to the incredible versatility of resistance bands and see how some of these applications can be utilized for the athletes or individuals you work with. My hope in this article is:

- To provide comprehensive descriptions of how and why to use resistance bands in training.

- To include for what populations or situations their inclusion would be pragmatic.

Given this is a rather extensive list of applications, let’s save the small talk and dive right in.

(To see a playlist of exercises in each category, click the subhead title.)

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9181]

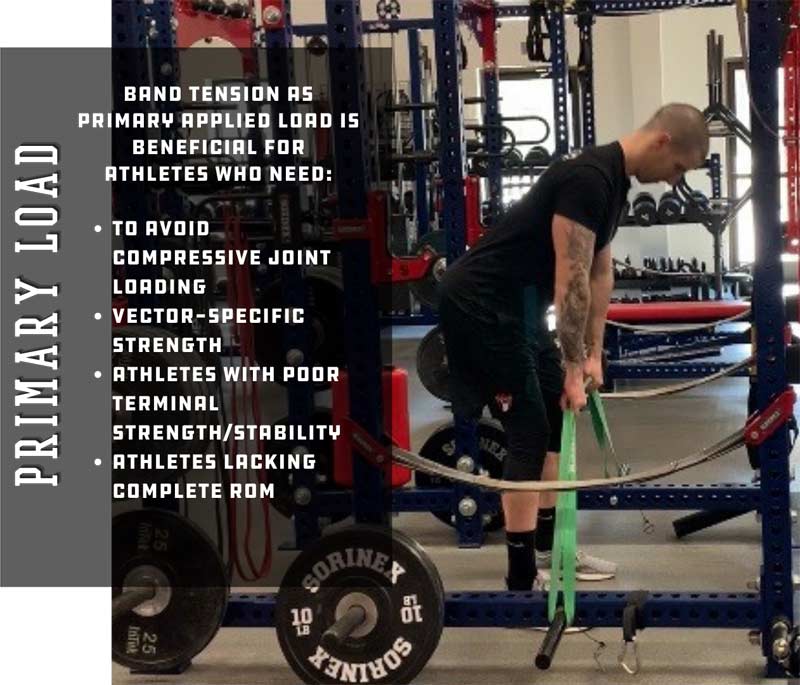

1. Applied (Primary Load)

When it’s the primary load, band tension provides an isoinertial resistance type, meaning the muscles are contracting against a constant resistance. This is the primary difference as compared to static load, in which muscular effort is variable throughout the range of motion (ROM) depending on joint position/angle (think about the top versus bottom portion of a dumbbell bicep curl).

Having the working muscle under tension throughout the entire ROM provides a greater total work output, increasing the workload efficiency. The load-length relationship is curvilinear, meaning the further the band is stretched, the greater the imposed resistance. As such, this provides an eccentric overload effect, placing an emphasis on terminal strength/stability. An important disclaimer here: Band tension is at its lightest resistance during the bottom ranges of motion (typically, deep flexion), so for this reason, it’s critical to recognize you still need to use static load to develop the complete ranges of motion.

Band loading offers the distinct advantage of loading multiple vectors or planes. Moreover, athletes can coordinate their most natural path of motion (POM) to achieve these certain movements. The precision and specificity of bands also make them great for confidence, which motivates the athlete to have more ownership over the movement. Being able to isolate and include very specific vectors is especially helpful for rehabbing injuries, but also for emphasizing positional/plane deficiencies or avoiding overstressing particular joints.

Band tension offers optimal muscular loading and tendon stretching while de-emphasizing compressive joint load. Because the moment arm is constantly changing throughout the POM, it prompts the athlete to position themselves for better mechanical leverage as they move. As shown by Jakobsen1, band tension may also produce greater muscle activation on certain exercises and at critical phases of these movements (e.g., tension increasing during a split squat at 10- to 30-degree knee extension).

Band loading offers the distinct advantage of loading multiple vectors or planes. Moreover, athletes can coordinate their most natural path of motion (POM) to achieve these certain movements. Share on XIt has also been shown there’s generally a greater proprioceptive demand when using bands. These subtle changes in how the movement is being executed challenge proprioception naturally and are a simple way to maximize your programming. In my opinion, this rep-to-rep variation provides a great stimulus that requires the athlete to remain alert throughout the entire set, as no two reps will be identical.

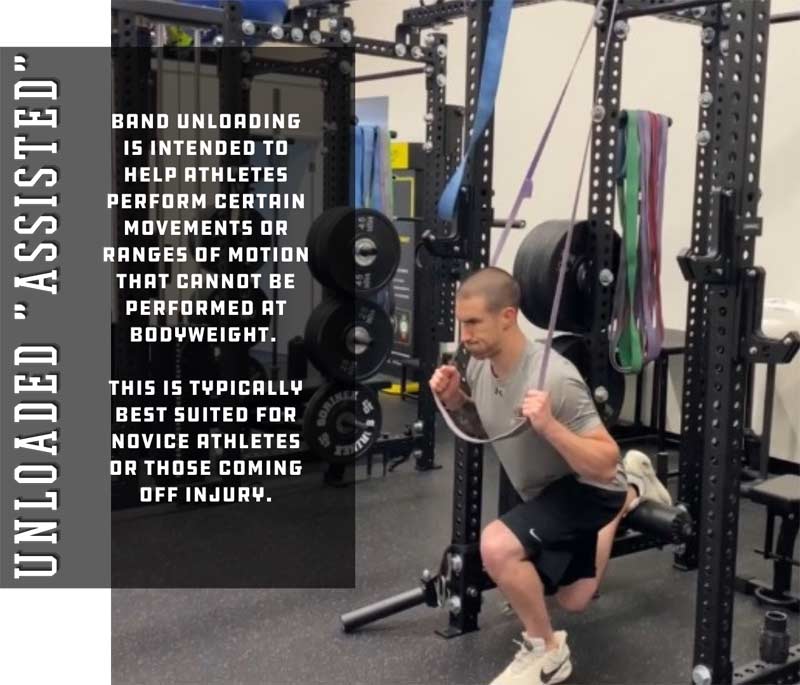

2. Unloading/Assisted

Band unloading is intended to help athletes perform certain movements or ROM that cannot be performed at bodyweight. This is typically best suited for novice athletes or those coming off injury.

This tactic has been particularly helpful for me when working with athletes battling chronic joint pain, recently coming off surgery, or who just have positional or localized weaknesses. Using band tension in this fashion creates an inverted length-tension relationship to the movement.

In other words, as the athlete moves into deeper ranges of motion (typically flexion), they are generally at their weakest point of the movement. Meanwhile, the band is being stretched to its greatest point, thus providing the most amount of assistance for the athlete. What this effectively does is reduce body mass proportionally to distance traveled and “unloads” the athlete in the bottom ROM. The band assistance can be progressively reduced and done so in a very incremental manner, providing a smooth and natural transition working back to bodyweight.

I also use this application for healthy athletes for a few reasons, though this is infrequent. The unloaded setup can be useful for athletes who need to monitor overstressing certain joints (e.g., tendonitis, arthritis) or just curbing stress accumulation altogether (e.g., in-season athlete, high-intensity training phases). A good example here is a band supported bent row for an athlete who battles mild low back pain but needs to strengthen their hinge position.

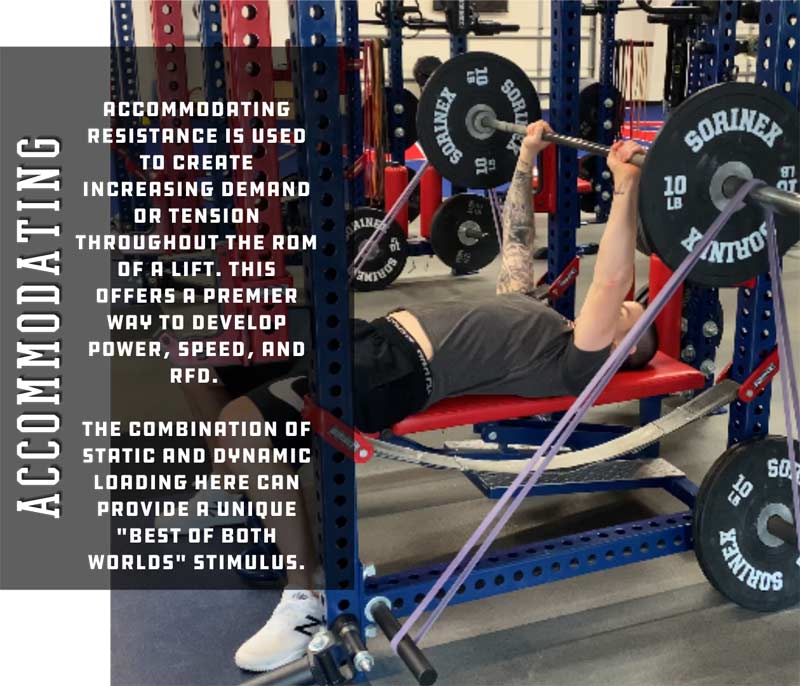

3. Accommodating (Static/Dynamic Hybrid)

Accommodating resistance—likely the most common band application—was popularized by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell in the early ’90s. As Louie has shown, this can be used for a litany of movements, but it is most commonly applied to compound primary lifts (i.e., bench/squat/dead) and common accessories such as RDLs, bent rows, and split squats. While Westside is obviously a powerlifting philosophy, there are several reasons to model these methods in the sport world—the foremost being that band tension is a great tool for developing speed and power. Accommodating resistance has been shown to be highly effective for optimizing power and rate of force output.2

Because of the increased resistance at terminal ROM, there is an increasing demand for acceleration as the athlete approaches end range. As such, they may offer an optimal application for the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC)3, as the tensile nature of the bands has shown to be beneficial for elastic strength properties such as tendon elasticity. Because band tension increases linearly with displacement, there is a greater demand for force output throughout the entire ROM as compared to the same load, but static.2 The force due to band tension in conjunction with forces due to gravity collectively challenges all structures and systems in a unique way, and when applied appropriately, can be highly effective throughout an athlete’s training cycle.

Athletes absolutely need both static and dynamic resistance types, and there are endless variables we could argue that will influence the rates, frequencies, and intensities at which each load type should be applied. All things being equal, however, I look at it like this: Develop functional strength through static load first and actualize the foundational strength through dynamic loading with more tenured athletes.

For young/novice athletes (less than 15 years old), static load is preferred due to its simplicity and general carryover. Similarly for developmental athletes (15-24 years old), static load is best for applying significant load and force, and dynamic loading can start to be introduced in a variety of situations. For this demographic, bands can start to have more practical inclusion and be sampled with big lifts. Dynamic load is best reserved for high-velocity/power loading, introducing new and multiple vectors, vector-specific loading, and general motor control/proprioception development.

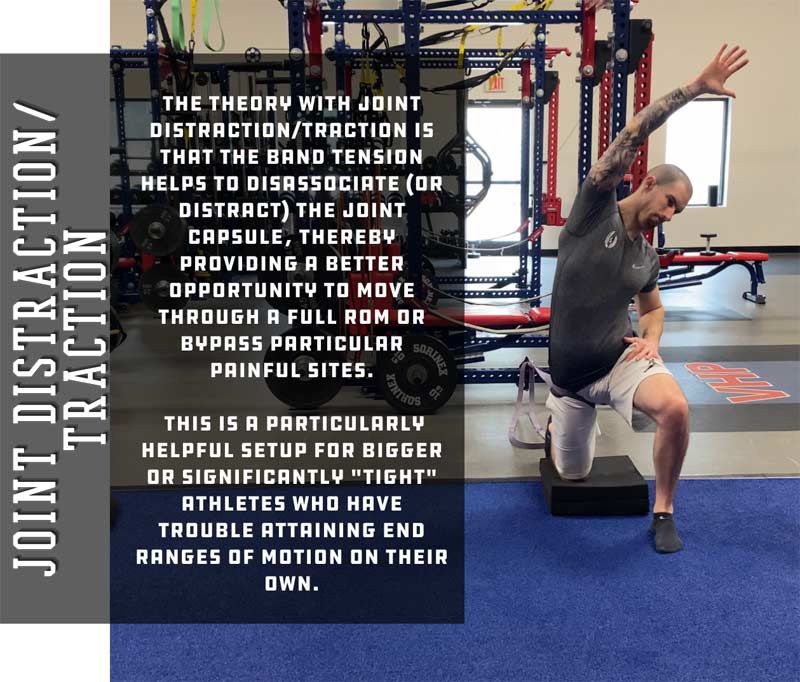

4. Joint Distraction/Traction</h2

Another method that has been increasingly adopted by coaches is joint traction, popularized by Kelly Starrett in his groundbreaking book Supple Leopard. The theory here is that the band tension helps to disassociate (or distract) the joint socket, thereby providing a better opportunity to move through a full ROM or bypass particular painful sites.

To my knowledge, there isn’t much (or any) formal research on the efficacy of joint traction. However, anecdotally, this method can help increase localized passive ROM, help with nerve/circulatory entrapment, and be an effective tool for improving joint capsule adhesion and immobility. Beyond the mobility component, I include this often just for the circulation effects. Even if it’s transient, increasing the localized presence of fluids such as synovial fluid, hyaluronic acid, and lymphatic fluid generally does more good than harm for the athlete.

5. Offset Loading

Offset loading is a much less common application, but one I’ve personally had a lot of success with. The thought process here is to use band tension as a means to load the frontal plane while performing a sagittal-based movement.

Video 1. Kettlebell Offset Band Split Squat.

This application can be simply and intuitively added to common movements (e.g., push-up/split squat/bridge), providing intermediate progressions. Say, for instance, a push-up progression is:

- Starting with bodyweight.

- Band offset.

- Plate loaded.

- Band resisted.

- Plyometric overspeed push-up.

In this fashion, offset resistance can be a foundational piece for developing robust rotational strength, as introducing a frontal plane tension specifically challenges trunk stability (anti-rotation/bending) and general proprioception. While the powerhouse rotational muscles include lats, obliques, the glutes, and adductors, smaller refined muscles such as QL, transverse abdominis, and erectors are also significant here. I believe offset resistance is an effective way to stress some of these smaller muscles that can be difficult to stress in conventional compound loading.

I believe offset resistance is an effective way to stress some of these smaller muscles that can be difficult to stress in conventional compound loading, says @danmode_vhp. Share on X6. Chaos Method

The chaos application has been scrutinized more than applauded, likely due to recent viral videos where it was shown in an imprudent fashion. I’ll say upfront this isn’t something that you should use often, and certainly not with athletes who lack foundational strength or stability. Nevertheless, when applied safely and correctly, this can be a great option to challenge motor control, muscular co-contraction, proprioception, and trunk stability.

I’ve also found this setup particularly useful for joint injuries—for my athletes with shoulder, wrist, or elbow pain/limitations, I use chaos push-up and inverted row variations in place of the traditional. This does two things:

- It removes the presence of compressive load (on the push-up), which reduces the magnitude of stress on the joint itself.

- The absence of external stability prompts greater demand on the joint receptors, along with promoting optimal co-contraction between muscle groups to create intrinsic stabilization.4

This can also be used as an advanced method—one that I was introduced to (extensively) by Cal Dietz. Using the heavy bands for movements like hamstring tantrums and cuff tantrums offers a unique way to create a massive overspeed effect, exposing the body to speeds it couldn’t reach normally. This application is believed to be effective for challenging autonomic (antagonist) inhibition, which would potentiate faster firing rates. The ballistic demand with this application makes it a great option during max speed/power phases, and it can be highly beneficial for the joint and soft tissue receptors.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11155]

7. Unloading (Supra Strength)

This form of band unloading is much less commonly practiced, but another one we can attribute to Louie Simmons and Westside Barbell. Also known as a “reverse band” setup, this application reduces the total mass of the barbell at the greatest point of strain. When using static load by itself, we are inherently limited by the concentric phase of the movement, as we are fundamentally much stronger eccentrically3. This means that when using static load, we are somewhat underloading the eccentric phase, and as we know, we are weaker in deep flexion.

So, with the unloading mechanism providing peak tension at the bottom portion of the movement, we get the most assistance when we need it most. I particularly like using this setup for bench press, rack pull, and overhead press, which are movements that typically have sharp sticking points.

Beyond using this to work supramaximal intensities, this approach can also be used for efficient volume accumulation. I add this into hypertrophy phases to perform “excess” volume without overtaxing the joints. An example, using the bench, would be:

- Finishing a primary block of 4×6 @ 80%.

- Then doing 4×6 @ 90% with band unloading as your secondary block.

While pure eccentric load is obviously needed, this can help pace the workload without having to get away from heavy loads entirely. This is another application that I’ve noticed older/veteran athletes tend to appreciate, and not even as supramaximal.

8. Unloading (Overspeed)

Finally, we have an overspeed application, which I was also introduced to via Cal Dietz. While this is similar to the supra strength application, here the bands unload body mass to allow athletes to move faster than they normally could. By doing so, it reduces the amortization phase of the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC), which promotes an accelerated contraction2. The overspeed method is another advanced tactic that shouldn’t really be utilized until foundational strength and speed have been well established. For advanced athletes, however, this is a fantastic programming tool that can help emphasize elastic/reflexive traits, speed, and proprioceptive response.

For advanced athletes, the overspeed method of unloading is a fantastic programming tool that can help emphasize elastic/reflexive traits, speed, and proprioceptive response, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XVideo 2. Band-overspeed depth jump to countermovement jump.

A few of my common go-to’s include pogo hops, RFE split jumps, and push-ups. And for advanced athletes, I like to use this setup for depth jumps as well (see above). It’s important these types of movements are coached clearly, and the movements must be executed with full intent. The purpose of reducing mass is to help move as fast as absolutely possible. A high intent and alertness are required to get the most of this type of application.

Bringing It All Together

As surprising as it may seem, there is still quite a bit unknown regarding resistance bands and their utilization or effectiveness in training. By far, the most important thing to recognize is intent is the key variable to it all. Whether using static or dynamic loading, the way in which that exercise is performed is often more significant than the exercise or load type.

Bands are extremely versatile, and while we’ve seen a few popularized applications over the years, I’d encourage you to examine some other ways to include bands (e.g., offset, unloading, vector-specific loading). Static loading is tried and true. When aiming for absolute force, the primary emphasis should be static loading. When emphasizing speed, power, motor control, or proprioception, dynamic resistance may be the better option.

Foundational speed/strength should be developed predominantly through static load before extensive band loading. Given the significantly increased demand for intrinsic stability with band loading, it may be imprudent for young and/or developmental athletes to prioritize dynamic loading. There is always a tradeoff between static and dynamic resistance. Understanding where your athletes are in their development and in their sport’s calendar are the critical variables to determine how much of each you should include.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Jakobsen, MD, Sundstrup, E, Andersen, CH, Aagaard, P, and Andersen, LL. “Muscle activity during leg strengthening exercise using free weights and elastic resistance.” Human Movement Science. 2012;32(1):65-78.

2. Walker, S, Blazevich, AJ, Haff, GG, Tufano, JJ, Newton, RU, and Hakkinen, K. “Greater strength gains after training with accentuated eccentric than traditional isoinertial loads in already strength-trained men.” Frontiers in Physiology. 2016;7:149.

3. Aboodarda, SJ, George, J, Mokhtar, AH, and Thompson, M. “Muscle strength and damage following two modes of variable resistance training.” Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2011;10(4):635-642.

4. Ebben, WP and Jensen, RL. “Electromyographic and kinetic analysis of traditional, chain, and elastic band squats.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2002;16(4):547-550.