Picture this: You are coming off a great winter track season. You’re getting ready for spring and about to have a preseason meeting. There are several upperclassmen on your team, and now you must decide who will be captain. You give it a lot of thought and decide on a junior because he has great leadership skills and is an outstanding overall team player—at the preseason meeting, you announce the decision.

Later that night, when you are home, you get a phone call from a disgruntled parent who TELLS you his son should be captain and that he is the fastest athlete on the team.

What do you say?

For me, the answer was: “I don’t choose my captain based on how fast an athlete can run, and although your son is a talented athlete, he isn’t the fastest. Your son has many positive attributes but is not quite ready to be in that position right now.” Over the years, I’ve found the best way to handle situations like this is to listen to what the parent has to say and then respond in as nonconfrontational a manner as possible (and if a situation does get escalated, then I would talk to my AD).

These lessons have helped me turn situations with teenage athletes and their parents into productive rather than destructive experiences. Share on XIf you’ve experienced similar situations dealing with teenage athletes and their parents, you’re not alone. I’m here to share five recommendations that I’ve picked up through 15 years of coaching that have allowed me to turn this scenario—and others like it—into productive rather than destructive experiences.

- Learn how to deal with teenagers.

- Know their why.

- Understand how each athlete learns.

- Accept that parents won’t always agree with you.

- Be okay with breaking your own rules.

1. Learn How to Deal with Teenagers

Understanding the physical and psychological development of high school athletes will ultimately benefit both the coach and the athlete. If you haven’t spent time with teenagers lately…this could be difficult. In my case, I have five kids of my own and have lived through the ups and downs of raising adolescents. In addition, my kids were very involved in organized sports (bringing with them a house full of their friends who were also teenage athletes). Having exposure to my own kids and their friends gave me an edge at understanding and working with this age group.

What can you do if you don’t have your own kids?

Interact with relatives around this age or friends who have teenage kids: spend some time with them and have conversations with them. Observe how they think and recognize what is important to them. Talk to them about their experiences with sports, but mostly listen and learn.

You will be spending lots of time with your athletes, and it’s a good idea to have some idea about how they operate. Coaching high school kids is an adolescent roller-coaster ride, and you just bought a ticket as they mature from insecure freshmen to confident seniors, with plenty of growing pains in between. I have learned that coaches become significant fixtures athletes depend on, so if you “get” them, they appreciate it, and things will go more smoothly.

Beyond that, take the time to learn to understand what motivates teenagers from an athletic standpoint. When it comes to figuring out what makes each athlete tick, late quarterback coach Tom Martinez describes it this way in the book Outliers: “Every kid’s life is a mix of shit and ice cream. If the kid has had too much shit, I mix in some ice cream. If he has had too much ice cream, I mix in some shit.”

Understand that these are kids, and sometimes it’s not their fault that they’ve been fed ice cream all the time and treated like everything they do is great. As coaches, we need to figure out strategies for dealing fairly with each of these extremes, as well as everyone and everything in-between.

Kids act a certain way for a reason. There may be pressures at home, school, or with peers that are having a significant impact on their behavior. Be aware of withdrawn, depressed, or concerning behavior—if you think there is an issue, don’t ignore it. All teens handle pressure differently.

If I suspect an athlete is acting differently, I ask how they’re doing I in a way that they won’t feel judged. The important thing is to listen. Share on XIn my experience, if I suspect an athlete is acting differently, I ask how they are doing in a way that they won’t feel judged. Kids have opened up to me about all kinds of things: bullying, depression, anxiety, and family issues. The important thing is to listen, and if you feel it’s something that needs to be further addressed, speak to the school counselor or parent.

2. Know Their “Why”

Why did this athlete come out for the team? What is their motivation for being there? You may think you know, but don’t be so sure—remember, your mind works very differently than a teenager’s.

With my athletes, during the first week of the season I started simply asking the question and having them write their answer down on an index card. Some of the responses I have gotten are:

- To get faster for a different sport.

- To keep in shape.

- To make friends.

If athletes come out for the team for non-competitive reasons—for example, just to make friends—I don’t care, because if they are a contributing factor and work hard, it’s all good. In some cases, they end up really enjoying the sport and flourish! If an athlete says they want to compete in college, then you can have the realistic conversation of what it takes and the standards they must hit. From there, you can be on the same page, and they know it will take hard work.

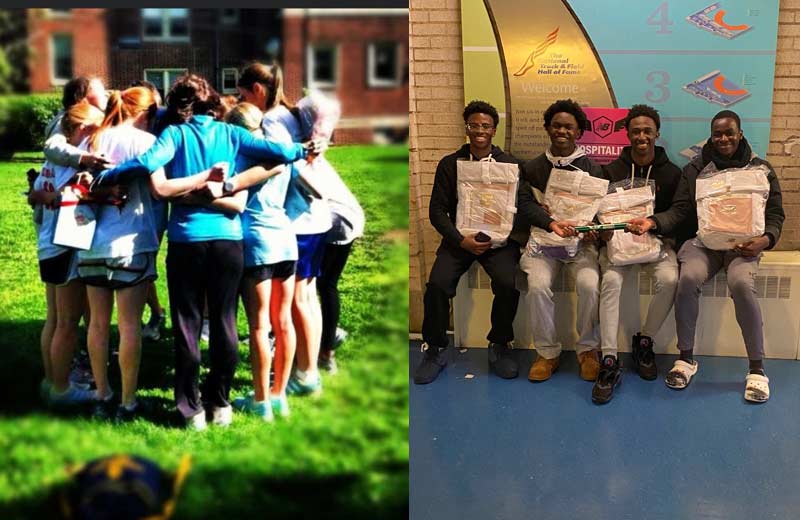

Some athletes need relationships before competition, others need competition before relationships. I believe this is where boys and girls differ—after spending my first seven years coaching in an all-girls school, then moving on to a coed high school, I have experienced a difference. Girls often value the relationship before competition, and boys the competition before the relationship.

Some athletes need relationships before competition, others need competition before relationships. I believe this is where boys and girls differ. Share on XTo help fill that social bucket, I have the athletes take an unstructured lap before we start practice. They can do it in groups or with one of their close friends, and it gives them a few minutes to unwind from their school day and socialize before we get started.

3. Understand How Each Athlete Learns

Aside from the psychological aspect of coaching, it is important to consider how each individual athlete learns. You can explain something to two equally talented sprinters, and one will get it right away and the other may need a physical demonstration. Some athletes are visual, some are auditory, and some need both. Add to this mix differences in chronological age, training age, social age, and personality, and you have a million different possibilities.

As an example, I will use two different long jumpers: one male, one female, both talented. Both juniors (and also talented sprinters), the male was jumping mid-22 feet and the female high-17 feet. When going over the penultimate step with both, the male became fixated on it and continued to overthink it, while the female just ran and jumped. This was how they approached school: one was an overthinker, and one was not. Make sure to adjust your coaching style to meet the needs of the athlete.

In the case of the two jumpers, what I found successful was to give much less technical information to the male jumper and work on only one cue at a time. For example, one cue I gave him was to focus on a tree visible in the sightline beyond the pit so he wouldn’t look at the board. This simple cue kept him in an erect upright position. As far as the female jumper…if it’s not broke, don’t fix it. If I showed her a video, she could adjust without too much of an explanation: less was more with her.

As coaches, it is our responsibility to get the best out of our athletes—to do this, you must realize no two are the same. Share on XAs coaches, it is our responsibility to get the best out of our athletes—to do this, you must realize no two are the same. Mike Boyle summed this up, saying: “Don’t strive to show how smart you are. Instead, strive to show what a great teacher you are. I believe the key to Keep It Short and Simple (KISS) is to strive to Make it Simple and Short (MISS).”

4. Accept That Parents Won’t Always Agree with You (and Five Keys to Building Successful Relationships)

When you have been coaching for years in high school, you end up dealing with hundreds of parents, and you can count on some of them not agreeing with you. I have had my issues in the past—and some of the parents have been difficult—but for the most part, the majority have been very pleasant.

Five keys I’ve learned over the years to establish successful relationships with parents are:

- Establish your expectations. Hold a preseason parent-athlete meeting, which can be over Zoom or in person. Discuss practice expectations for parents and athletes, uniforms and practice wear, competitions…anything you as a coach find important to running a successful team. You will find that some of these items stay constant over the years and some change. As we all know, this last year was very different and, as a result, so was the information we covered.

- Review your school’s athletic department policy. Get to know your Athletic Director and their school-wide policies—every school is different. Help them understand your coaching style and what your goals are. You want to make sure your AD has your back as a coach and will stand up for you when needed. I have had outstanding ADs who were always willing to help and do what was best for the athlete, coach, and program.

- Write and distribute your own rules and expectations. When things are in writing and everyone is on the same page, it prevents future problems.

- Review your team goals, priorities, and philosophy. These are some of the first things covered in the beginning of the season. Also added to this list are personal goals athletes have for themselves and upperclassmen’s desire to play at the next level. (That’s a discussion for another article.)

- Encourage athletes to speak with you before bringing a parent into the conversation. When students start high school, I encourage them to learn to advocate for themselves. If they have a problem, they should speak to the coach first instead of having their parent call. I also encourage them to speak to the captain if it is something they think is appropriate. This allows captains to become leaders and problem-solvers. If the captain thinks it is something that needs to be discussed with the coach, they will direct it that way. I have found this a great way to teach many different lessons to athletes.

5. Be Okay with Breaking Your Own Rules

Rules are essential for any successful team, BUT it’s also important to know there are exceptions to the rules. You’re the coach—when you feel you need to break them, it’s okay; you just need a valid reason.

For example, one of my rules for practice over break was that you had to make at least four of the practices during the week to compete. One athlete was not showing up to most of the practices. When I asked him about it, he told me he lived with his mom, and she had to work—and that it took him two hours to get to practice with public transportation. That would be four hours a day to get back and forth to practice. In my book, this is a valid reason for me to break the rules.

A Coach Is Always Needed

In Martin Rooney’s book High Ten, I found the quote “Because everyone always needs a coach, a coach is always needed.” This is a sentiment many of us feel and the reason why we should evaluate and reflect on lessons we have learned from year to year. Every year I learn something new, whether it is how to better train my athletes, communicate with them, or create a better team culture. These are the things that keep us doing what we love and motivate us to move forward.

This past year was very difficult for athletes and coaches because of the pandemic. When I reflect, I think about how happy I was, first just to get to coach at all, and then with the performances: a freshman male breaking 11 seconds in the 100m and freshman female hitting a 12.2. Those are the things that get me excited, but I also think about how disjointed the team felt.

This is when I must think about the team culture and what it was lacking. We had kids missing numerous practices, relays that weren’t cohesive, and athletes not reaching their potential. I just figured it was a pandemic and need to ease up on them, but I was wrong, and I learned some new lessons that will help me.

How do I move forward and improve my team? I take my notebook and write down what kind of team culture I want to create. Our motto will be #trusttheprocess, and I will get wristbands to remind them.

How do I start to create team culture? It starts with the coach motivating them to believe in themselves and the team—behaviors reinforce our beliefs and that will lead us to where I think we should be as a team.

After 15 years of coaching high school track and field, I know I LOVE it and NEED to do it, but I also need to learn from my own lessons. I hope that my years of experience will get you thinking and sharing with other coaches—at the end of the day, as one of my ADs said to me, “you are changing lives, one at a time.”

If you’re a coach starting out, there will be days you go home and feel like hanging up the stopwatch and clipboard. DON’T! It will get better. Share on XIf you’re a coach starting out, there will be days you go home and feel like hanging up the stopwatch and clipboard. DON’T! Trust me, I have been there, and I still have my moments, but it will get better. Taking the coaching roller-coaster ride with your athletes over their high school career is something you don’t want to give up on. The enormous sense of pride and satisfaction far outweighs the frustration you may feel from time to time.

Look at your coaching journey as an education: the lessons you learn from one season will benefit you in the next. The first year you coach you are like a freshman; four years later you are a senior. One day you will turn around and 15 years will have passed, and you will realize how many young athletes you have helped—and that’s worth it because if you are a coach, you NEED to help people.

I hope my lessons will help you. Hold on tight and enjoy the ride!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF