Let’s face it—the world of electromyography (EMG) can be intimidating. But if you’re serious about sports performance or rehabilitation, understanding muscle recruitment dynamics isn’t just nice to have—it’s becoming essential.

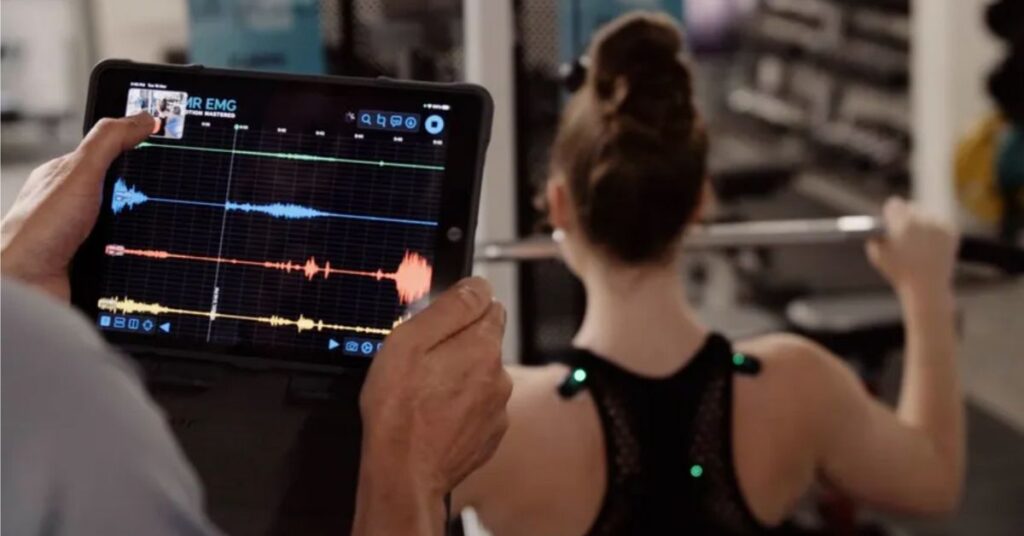

I think the reason why there’s an intimidation factor is because this is a rare instance of injecting medical-grade technology involving a decent amount of data into the weight room. But it doesn’t have to be intimidating, and the data can be reasonably straightforward while leading coaches to actionable insights. Whether you’re a strength coach looking to optimize an athlete’s performance or a physical therapist guiding someone through recovery, EMG technology offers incredible insights that were once only available in research labs.

Whether you're a strength coach looking to optimize an athlete's performance or a physical therapist guiding someone through recovery, EMG technology offers incredible insights that were once only available in research labs. Share on XWhat’s EMG Anyway and Why Should You Care?

EMG, short for electromyography, captures electrical activity from your muscles—either directly from the muscle itself or from electrodes placed on your skin. Think of it as eavesdropping on the electrical conversations your muscles are having when they work.

The applications? They’re pretty exciting:

- Researchers use EMG to uncover relationships between muscle firing patterns and movement.

- Therapists use it for biofeedback, helping patients to reestablish neuromuscular dialogue—assessing efficient communication between brain and body (or software and hardware, as it were).

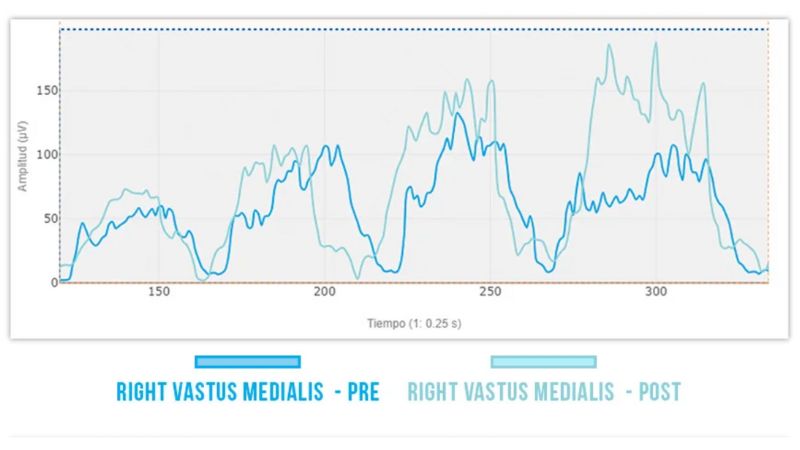

- Performance coaches can use EMG to pinpoint inefficiencies in an athlete’s movement and potentially identify neuromuscular deficits and/or asymmetries.

The coolest part? What was once bulky and financially-out-of-reach research equipment is now available in smart textiles and wearable tech, making EMG accessible for everyday training and rehab scenarios. Practitioners can use EMG insights in order to provide a type of biofeedback in order to enhance “mind-muscle” connection. It’s also possible to get clinical-grade insights into strengthened (post-training intervention) or weakened (early-stage rehab scenarios) neuromuscular dialogue as well as identify key asymmetries.

What was once bulky and financially-out-of-reach research equipment is now available in smart textiles and wearable tech, making EMG accessible for everyday training and rehab scenarios, says @RewireHP. Share on X

Is EMG Right for Your Setting?

Let’s be honest—EMG isn’t for everyone. Applying the technology requires knowledge, some experience, time, and the right corresponding workflow (process) to be truly effective.

For EMG to really work in your program, you’ll need:

- Actual time to collect, analyze, and act on the data (no, it’s not a “set it and forget it” tool that athletes can self-apply).

- Manageable group sizes—you can’t effectively monitor 30 athletes simultaneously, making the tech instead ideal for one-to-one or ultra-private settings.

- Buy-in from your athletes—they need to be engaged in the process. Don’t invest in EMG as a perceived value-add if you’re not really engaged in using it to guide your correctives/training process on the whole.

Feeling overwhelmed already? Don’t be. While adding another technology might seem daunting when you’re already time-starved, the right EMG setup can actually prevent bigger problems down the road. It’s especially valuable in return-to-play scenarios, where athletes often wonder “Is my muscle actually firing in the right patterns with as high a level of signal activity as it was pre-injury?” That peace of mind alone can be worth the investment, because it provides a form of objective feedback so clients can see their progression.

While adding another technology might seem daunting when you're already time-starved, the right EMG setup can actually prevent bigger problems down the road, says @RewireHP. Share on XThe Nitty-Gritty: How EMG Collection Actually Works

There’s no way around it—proper EMG requires some setup. For larger, prime mover muscles (think quads or hamstrings), skin electrodes work well. Smaller muscle groups might require fine wire methods (yes, that means what you think it means).

Before testing, you’ll need to:

- Shave and clean the skin where electrodes will be placed.

- Establish baseline measurements through isometric/contraction testing.

- Understand how to clean up signals and interpret the data.

The good news? Modern software handles much of the heavy lifting with data processing. The challenge is contextualizing that data to make it meaningful for your specific athlete and situation.

Your EMG Options: From Research-Grade to Wearables

The EMG market has evolved dramatically. Today, you have two main paths:

Research-Grade Systems: These offer precise targeting of specific muscles (remember, “hamstring” isn’t one muscle but three: semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris). These systems deliver wireless connectivity and real-time feedback with high accuracy. That said, if you’re a coach or rehab specialist reading this—the more advanced systems probably aren’t practical or necessary.

Garment-Based Systems: These smart textiles provide general insights about muscle activation areas rather than pinpointing specific muscles. They’re more convenient, but less precise. They can potentially be effective for getting more global, workable insights that can inform training decisions.

Buyer’s bottom line? If you need publication-quality data, stick with higher end, research-grade equipment. If you’re looking for practical feedback to guide training or rehab, basic systems or garment options might suffice—especially for easy-to-measure tissue sets like the glutes.

My take from a coach’s perspective is that EMG is a worthwhile investment IF you are involved in rehabilitation and/or performance rehab. I don’t feel some practitioners in the space—even if they see the value in EMG—will ultimately need it for their day-to-day training. A speed coach, for example, isn’t going to see this as a worthwhile investment. That said, many movement-based coaches who work with athletes that are in some level of pain or are having some level of dysfunction can find a ton of value in using it as an assessment tool and progress tracker. EMG will also provide objective data for clients, which enables more buy-in at the end of the day.

If you need publication-quality data, stick with higher end, research-grade equipment. If you're looking for practical feedback to guide training or rehab, basic EMG systems or garment options might suffice. Share on XThe Technical Stuff Made Simple

Every EMG system has three key components:

- Electrodes: These capture the electrical signal from your muscles.

- Signal relay: This transmits the muscle information to a receiver.

- Receiver: Usually connected to a computer that processes the data.

Raw EMG data looks like squiggly lines that won’t mean much to most people. That’s where filtering comes in—cleaning up the signal to extract meaningful information. Good software will handle this and present the data in ways coaches and therapists can actually use.

Top EMG Systems in the Market

Research-Grade Systems

Delsys – The research powerhouse founded by EMG pioneer Carlo De Luca. If universities and hospitals trust Delsys for clinical-grade insights, you know it’s serious business. Their wireless systems offer real-time biofeedback and exceptional signal quality.

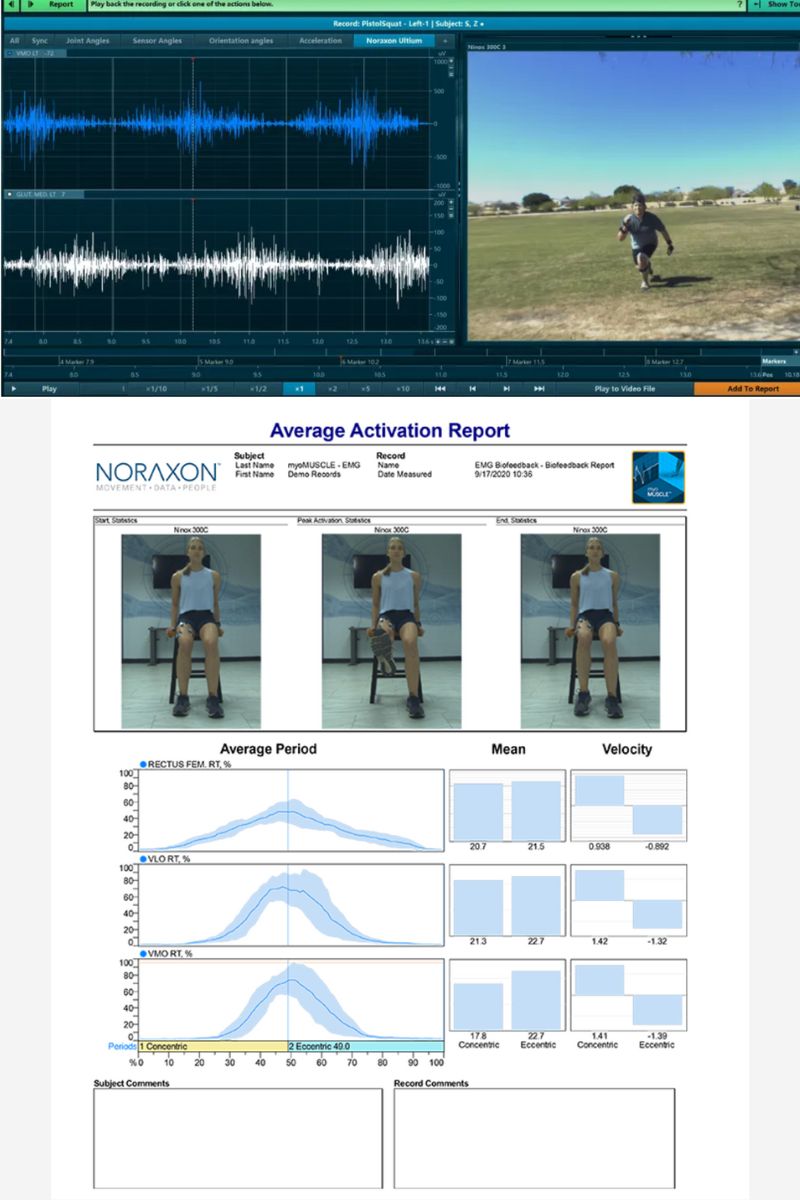

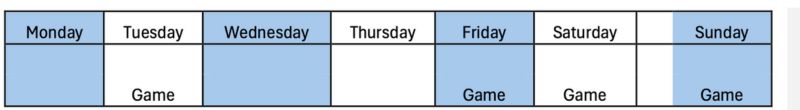

Noraxon – The Swiss Army knife of biometric data. Their user-friendly software can integrate data from multiple sources, making them popular in clinical settings, universities, and pro teams. Their reporting features are particularly impressive. Depending on setup and budget, Noraxon are a company that has been able to find success both with options in research settings as well as in the private sector. They also feature such a wide-array of diagnostics that practitioners have the option to fold in EMG into the greater context with a battery of other tests (e.g., pressure mapping, force plate data, and much more).

BTS Bioengineering – This Italian company brings both style and substance to EMG research. Their design-focused approach makes their systems both powerful and aesthetically pleasing.

CONTEMPLAS – This German company integrates EMG with force analysis and video capture. Their all-in-one software approach makes them popular with running stores and bike fitting specialists.

MuscleLab – A pioneer in sports science tech, this Norwegian company seamlessly integrates EMG with force, motion, speed, and contact measurements. Their tablet compatibility makes MuscleLab great for field testing. This is ideal for coaches looking for an approachable, portable option as opposed to some of the comparatively more involved, research-grade options.

Cometa – This Italian company has carved out a niche with waterproof EMG for aquatic movement assessment. They’re particularly visible in sport applications across Europe. What’s interesting is that pool training (or aquakinetics, as we’ve written about before) is actually an ideal pair with EMG—they involve similar assessments and corrective exercise, as it offers an ability to load the body in entire patterns as opposed to “isolated” muscle actions.

BIOPAC – A staple in academic research, BIOPAC offers reliable EMG as part of their broader biosignal equipment lineup. They’re primarily focused on research applications.

Shimmer – This Irish company provides biosignal solutions beyond just EMG. They’re expanding globally with offices in Asia and North America, focusing on both clinical and research applications.

Cadwell – Specializing in electrodiagnostic equipment, Cadwell combines EMG with electrical muscle stimulation. Their systems are particularly valuable for nerve testing and function assessments.

Convenient Wearable Systems

Somaxis – Their inexpensive biosignal system connects directly to smart devices via Bluetooth and captures not just muscle activity, but also heart and brain electrical signals. A great entry point into EMG.

Myontec – The pioneer of EMG shorts, this Finnish company offers garments that measure muscles below the hip, with options to include glute measurement. They’re making inroads with teams worldwide.

Athos –This California startup offers full-body monitoring with garments for both upper and lower body. Their cloud-based platform and web portal make them popular for team environments and return-to-play scenarios.

Additional Systems Worth Considering

Myon – Swiss precision meets EMG. Their systems offer exceptionally low latency and high sampling rates, making them ideal for synchronizing with motion capture systems. Myon is particularly popular in research involving rapid movements—making them potentially attractive for sport with this ability to examine movement at velocity.

TMSi – This Dutch company specializes in ultra-low noise amplification, making their systems excellent for detecting subtle muscle activations. Their Mobi system offers clinical-grade EMG in a portable package.

Trigno™ by Delsys – Their specialized sensors combine EMG with accelerometry, allowing simultaneous measurement of muscle activity and movement. The latest versions include additional physiological sensors for comprehensive monitoring.

XsensDot with EMG module – Combines inertial measurement with muscle activity monitoring, allowing for detailed movement analysis alongside EMG data. Their fusion algorithms help correlate motion patterns with muscle firing.

Plux Biosignals – Their modular approach allows you to build custom EMG setups based on your specific needs. Popular in both research and clinical applications where flexibility is valued.

GripAble Pro – Specialized for hand and forearm rehabilitation, this system combines EMG with grip strength measurement and gamified exercises. Particularly useful for stroke recovery and hand injury rehabilitation.

mDurance – This company has been making waves in Spanish-speaking markets and offers a highly reliable, robust system with easy-to-interpret data for practitioners.

MR EMG – Another company to watch, they have silently been building a strong reputation for delivering accurate data that’s reliable for coaches to integrate into their training process to monitor before and after results of training interventions.

References

“Electromyographic Asymmetries During Fatiguing Exercise: Influence of Lateral Dominance and Fatigue.”Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 2014. DOI: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2013.12.004

“Comparison of Muscle Activation Patterns Using Surface and Intramuscular EMG during Dynamic Movements.” Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 2012. DOI: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2012.04.002

“The Use of Electromyography to Measure Muscle Contraction Velocity and Its Correlation with Force Production in Resistance Exercise.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, 2011. DOI: 10.1007/s00421-010-1864-1

“Use of EMG to Quantify Muscle Fatigue during Static and Dynamic Muscle Contractions.”

Journal of Applied Physiology, 2006. DOI: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00464.2005

“EMG Signal Changes as Indicators of Muscle Fatigue during a High-Intensity Resistance Exercise Protocol.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2013. DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828c2d01

“Asymmetry of Muscular Activation During Functional Movement Tasks in Athletes.” Sports Medicine, 2017. DOI: 10.1007/s40279-017-0740-7

“EMG and the Timing of Muscle Activation during Rapid and Slow Movements.” NeuroReport, 2015. DOI: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000406

“Real-Time EMG Monitoring to Detect Fatigue in Skeletal Muscles during Continuous Exercise.”

Clinical Neurophysiology, 2010. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.09.004

“Effect of Muscle Fatigue on the EMG Signal: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 2017. DOI: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2017.06.005

“Asymmetry of Electromyographic Activity and Its Correlation to Performance in Healthy and Injured Athletes.” Sports Biomechanics, 2016. DOI: 10.1080/14763141.2016.1153447

![The graph illustrates two sinusoidal waveforms akin to resisted sprints: a black line with increasing amplitude and a magenta line with higher peaks. The x-axis reads Position [n] while the y-axis is marked as Power [W].](https://simplifaster.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Screenshot-2025-03-23-at-2.00.16 PM.png)