This article is designed to be a one-stop shop for coaching the 4x200m relay. We will not delve into energy systems or specific training strategies for the 200m dash but will instead focus on the unique aspects of the 4x200m relay (especially practicing the handoffs). Hopefully, there is enough here for the beginning coach to get a grasp on the event while also introducing some new elements to help experienced coaches.

I. Why Is the 4x200m Relay Unique?

Let us be brutally honest here: the 4x200m relay is often seen as a B-team relay, especially until the championship season begins. The 4x100m, 4x400m, and 4x800m relays get significantly more glory across most of the year. This is partially because many states did not even compete a 4x200m relay at their championship series until this millennium. Some still don’t compete a 4x200m at State.

Another reason the 4x200m relay is an afterthought is because it is crammed right in the middle of the meet. In Illinois, the 4x800m and 4x100m relays are the first two running events, and the 4x400m relay, of course, ends each meet. The 4x200m relay is stuck right in the middle, with the 400m dash and 300m hurdles coming right after it. That pulls out a lot of people who would potentially be running on a team’s A 4x200m relay.

Illinois allows athletes to compete in four running events, which means you will often see athletes competing in the 4x100m, 100m, 4x200m, and 200m. But in some states (like Wisconsin), athletes are limited to just three running events. That pulls a lot of athletes out of the 4x200m relay, especially when you factor in athletes running the 300m hurdles, 400m dash, and 4x400m relay. Additionally, coaches are becoming more aware of not overloading athletes before the championship meets, which means limiting events. The 4x200m relay is often the first event dropped from a top athlete’s docket.

Despite all the problems with the 4x200m relay being difficult to load during the season, one fact remains: the 4x200m still counts for the same number of points as the 4x100m, 4x400m, and 4x800m.

Video 1: If you have never seen a 4x200m relay before, it is quite a spectacle. Since the race is run in lanes the entire time, the opening stagger is huge. There are a variety of handoff techniques, lineup decisions, and race strategies to consider.

II. What’s Great About the 4x200m Relay?

One great benefit of the 4x200m relay early in the season is providing those “B-team” athletes with a chance to get varsity experience. In 2016, we had a great sprint crew and did not fully load our A 4x200m relay until the Sectional Championships. We had nine athletes win outdoor invitationals for us in the 4x200m relay that year.

As a coach, in order for you to make this relay an important breeding ground for success during the season, you have to treat the 4x200m like an A relay. Attitudes are contagious, so even though I have spent the majority of this article so far telling you why the 4x200m relay does not get respect, you need to make sure you emphasize and prioritize it.

III. Picking a Lineup

The 4x200m relay is not quite as complicated as the 4x100m relay, and your four best available 200m runners will almost always end up on your 4x200m relay A team. Unlike the 4x100m relay, where you ideally want to stick with the same four athletes all year, switching up the 4x200m relay is much easier.

This is a unique sprint relay in the sense that every athlete runs almost the same leg. In a 4x100m relay, some athletes run curves while others run straightaways, and some athletes run with the baton in their left hand and others in their right hand. In the 4x400m relay, the leadoff is in lanes the whole time, the second leg has to cut in, and the third and fourth legs must worry about catching a baton in traffic. But in the 4x200m relay, every athlete runs a corner and a straightaway in their lane the whole time.

There are some unique aspects to the 4x200m that make choosing a lineup very important. The most obvious is that the leadoff athlete comes out of blocks, so you should aim to put a good starter on that leg. However, I believe this is the relay where getting a lead early is least important.

I believe the 4x200m relay is the relay where getting a lead early is least important, says @LFHStrack. Share on XIn the 4x100m relay, the stagger is so small that athletes can gauge their position early on, so having a lead gives a psychological advantage. In the 4x400m and 4x800m relays, getting a lead early is very important to make the handoffs easier. But in the 4x200m relay, the race is run in lanes with such a huge stagger, and the handoff zone is so large (30 meters) that most athletes cannot tell where their position is early in the race. The psychological advantage is much lower. Ideally, you would have your leadoff get you in first place, but that’s not as essential as it is in the other relays.

The main difference in the leadoff leg is the large, somewhat ridiculous stagger. When you run a 200m, you expect to have about 100 meters on a curve and then 100 meters on a straightaway. However, the leadoff runners in the outside lanes can end up running about 35 meters on a curve, 100 meters on a straightaway, and then another 65 meters on the curve. This makes the race difficult to approach strategically. The later you get in the legs, the more the ratio “evens out” and the more similar to a regular 200m race you get. If you have an athlete who has trouble with race modeling, for whatever reason, put them on the later legs.

If you choose not to switch hands with the baton, you will have to consider which hand the athletes are comfortable carrying the baton in. The standard is that the leadoff and third runners carry the baton in their right hand, the second leg carries it in their left, and the anchor leg catches it left and can choose whether or not to switch it to their right hand. However, because all the athletes will run a corner and a straightaway, you can be much more flexible.

For example, your leadoff can run with the baton in the left hand without any issue. You can even have some athletes switch hands and others not. But whatever you choose to do, the athletes must be completely aware during practice and certainly before the race begins.

IV. Handoffs

Without question, the 4x200m relay handoffs are the most complicated. With the exception of the baton position, 4x100m relay handoffs are pretty standardized and relatively easy to practice. Handoffs for the 4x400m and 4x800m relays are open and relatively easy to practice and execute. However, there are many options for 4x200m relay handoffs, and many of them are extremely difficult to practice (due to factors we will discuss). First, let’s talk about the givens.

Lane Discipline

At all times and in all races, lane discipline must be maintained. Simply put, the athletes need to leave enough space in the lane so they don’t tangle up their legs with one another. The general rule is that the baton always stays in the middle of the lane. So, if the incoming runner has the baton in their right hand, they will be on the inside of the lane; this means the outgoing runner will receive the baton in their left hand and be on the outside of the lane. Regardless of the style of handoffs you perform, you need to follow lane discipline.

Handing Off in the Zone

The new 30-meter exchange zone simplifies handoffs because athletes no longer need to worry about handing off too early. The expanded exchange zone also adds the possibility of extending certain legs. Theoretically, the middle runners (second and third legs) could run a 230-meter leg if they caught the baton at the very beginning of the zone and handed it off at the very end.

Handing off at the very end is risky, of course, and nobody catches it at the very beginning unless there is a problem. However, a crafty coach could definitely manipulate the zones a bit to get the fastest athletes the baton for longer while minimizing the baton time of the slower athletes. In a race often won by hundredths of a second, this could be the difference between winning and losing.

At the 2022 Sectional Championships, our 4x200m relay team had two athletes who were a step above our other two. We put one of the studs on the second leg and our fastest athlete on the anchor leg. Those two athletes started at the very back of the zone, while our third leg started about 15 steps ahead. This extended the distance our two studs had to race with the baton and, therefore, shortened the distance of our other two athletes. The strategy worked as we beat the qualifying time by just 0.19 seconds.

Note also that the athletes must start inside the zone. They cannot have any part of their body make contact with the track outside the beginning of the zone. For a legal handoff, the baton must be passed within the zone. This means that it is possible that the outgoing runner’s feet will be outside the zone, but the baton is passed within the zone, and the handoff is legal. The baton is what counts, not the runner.

Now let’s get into some of the options you have when practicing and completing 4x200m relay handoffs, in order.

Stance

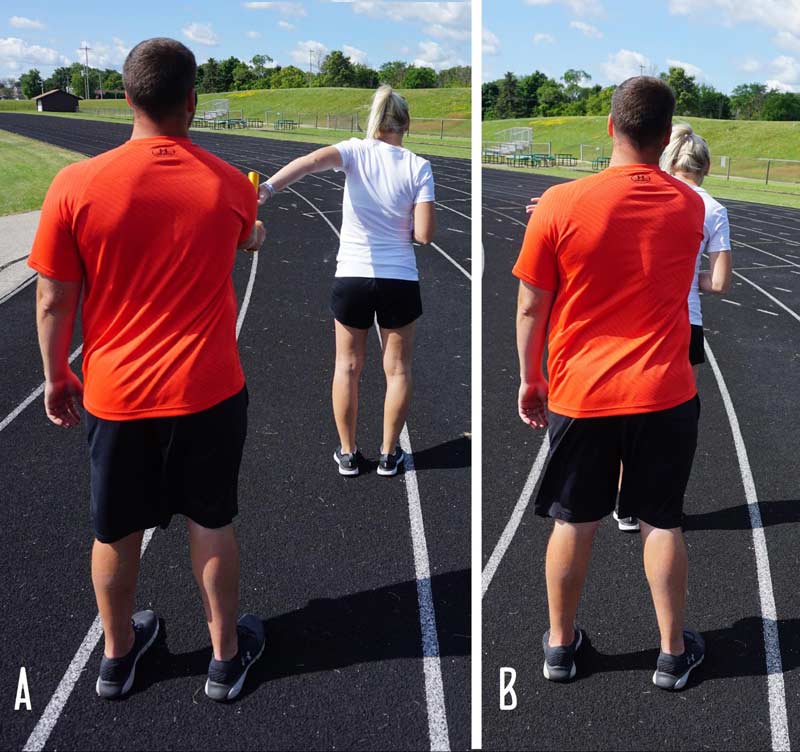

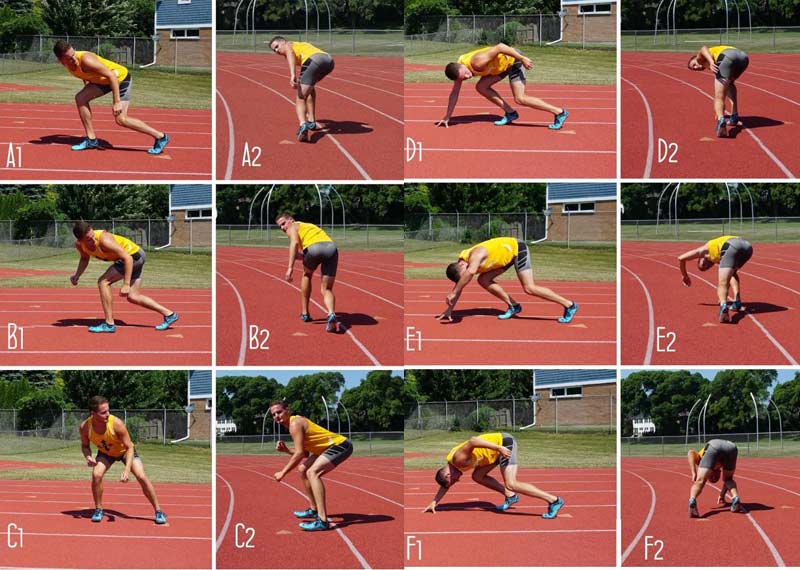

When choosing a stance, the outgoing athlete needs to be in a position to sprint and see the incoming runner. All the stances shown in image 3 accomplish that task; however, I must advise against choosing stance C due to butt interference. Please, please, please do not teach your athletes this stance. In fact, actively encourage your athletes to avoid it.

Firm ground contact will not only allow the athlete to be faster out of the stance but also will increase consistency, says @LFHStrack. Share on XFor high school athletes, I recommend stance A. It is versatile, simple, and appropriate for the speed of high school athletes. Regardless of the stance you choose, a great piece of advice for the athletes is to make firm contact with the track with both feet as they get into their stance. Some athletes are jittery and bounce around a bit; others are more timid and will only have soft contact with the track as the incoming runner approaches. The ground contact needs to be firm, just as if the athlete was putting pressure on the starting blocks. Firm contact will not only allow the athlete to be faster out of the stance but also will increase consistency.

“Go” Marks

Since the timing of the 4x200m relay handoff is critical, using a “go” mark is essential. The mark offers a visual cue for the outgoing runners to start their acceleration. You can either have the outgoing runner anticipate when the incoming runner will hit the mark, or you can have the outgoing runner begin acceleration when they see the incoming runner hit the mark.

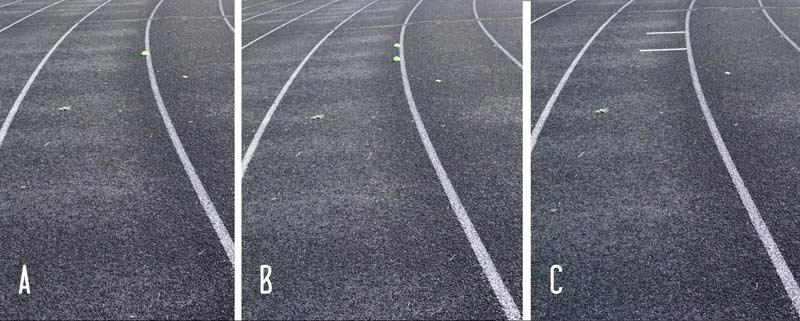

Though there are many items you can use as a go mark (in a pinch, I’ve seen athletes use dandelions or even their own spit), the standard items are a tennis ball cut in half or a piece of athletic tape. Certain tracks and competitions have rules for what is allowed, so be sure you know going into a meet what marks are available. Most high school meets allow tennis balls or chalk marks, while most college meets allow tape. Image 4 shows what some of these marks look like from the outgoing runner’s point of view.

One decision you have to make as a coach is whether to use one mark or two. When using two marks, the athletes look at a zone versus a single mark. Generally, this zone is 3–5 steps long. When using a zone, the outgoing runner goes when the incoming runner steps into the zone.

As a coach, I have my athletes use one mark because that gives the outgoing athletes only one object to focus on instead of two.

One decision you have to make as a coach is whether to use one ‘go’ mark or two. When using two marks, the athletes look at a zone versus a single mark, says @LFHStrack. Share on XIf you choose to use tennis balls for your go marks, always keep plenty on hand. I suggest going to the tennis coach and asking for all the old tennis balls they are done using. Cut them in half, draw your team logo on them with a marker, and keep at least two dozen on hand at practice. Give one to the athletes who consistently need them at meets, and keep plenty in your coaching bag. An athlete scampering around before a race trying to find a tennis ball is not in the state of mind you want heading into an important race.

Another option is to use the exchange zone itself as your go mark. Due to the large zone (30 meters), you might not want every athlete starting at the very beginning of the zone. So you can have your athletes use the mark for the exchange zone itself as their go mark. See video 2 for an example of how to use the zone or an object as your go mark.

Video 2: Using the exchange zone as your go mark versus using an object as your go mark. Notice also that the athletes must start inside the zone. In both examples, you will notice he uses 15 steps.

Steps

Once you have figured out where to start and what to use as your go mark, you must figure out how many steps to put between the two. These steps are usually measured by having the athletes mark them off heel-to-toe (see video 2). In general, the faster the incoming athlete, the more steps you need to take. We usually start the season with everyone using 13 steps and adjust from there. By the end of the season, most of our varsity athletes are using 15–16 steps.

While the number of steps largely depends on the speed of the incoming runner, there are a few other factors in play. One is the speed of takeoff (which I’ll cover in the next section), and another is how you choose to use the go mark. If you choose to have your outgoing runners anticipate the incoming runner hitting the go mark, then they will use a relatively low number of steps (12–16); if you choose to have your outgoing runners start acceleration as soon as they see the incoming runner hit the go mark, they will use a relatively high number of steps (16–20).

Speed of Takeoff

One of the most difficult decisions you need to make is how fast the outgoing runner needs to start off. The general principle is to match the speed of the incoming runner. This is fairly easy in the 4x400m and 4x800m relays and also relatively easy in the 4x100m relay because virtually every outgoing runner starts off at 100%. There is some subtlety to the speed of takeoff in the 4x200m relay, with little margin for error, which makes it an extremely important skill.

One option is to start as fast as possible, just like in the 4x100m relay. However, there are two potential downsides to this strategy:

- Sprinting at top speed makes it very easy to run away from the incoming runner, who is fatigued and losing speed.

- The steps will need to be shortened due to the increased speed of takeoff, which means the incoming runner will be quite close to the outgoing runner as the outgoing runner takes off. This naturally triggers a “defense mechanism” whereby the incoming runner slows down for fear of running into the outgoing runner.

Due to the problematic nature of this strategy, I do not recommend the outgoing runner starting off at 100% in the 4x200m relay. Instead, I recommend the runners start off around 80%–90% of their top speed. This is not a fool-proof strategy, however. High school athletes notoriously struggle with estimating their perceived speed. Tell them to run a 32-second 200m rep; some will run 26 seconds while others will run 38 seconds.

If you tell your athletes to go out at 85%, they will likely perform well in practice where there is minimal pressure. However, when the pressure is on in a meet, those same athletes might fall back on one extreme or another. Just about every coach has stories of athletes who either start way too fast or way too slow when the pressure is on.

This is why practice makes perfect. The more practice the athletes get with the proper takeoff speed, the more prepared they will be in meet situations.

Another way to reinforce this delicate takeoff speed is to implement it in practice situations outside of specific handoff work. For example, if you do submaximal repeats, you can instruct your athletes to start at the same speed (85%) on every rep. That way, when you describe what you look for in the 4x200m relay takeoff speed, you can say it is the same takeoff speed as your submaximal reps.

Commands

If you do blind handoffs for the 4x200m relay, you must set up commands. For a verbal command, the incoming runners will yell out Stick! when they are ready to hand off the baton. Your athletes can yell out whatever they want, but Stick! seems to be the consensus.

The timing of this command is critical, as many beginners yell too late when a little anticipation is needed. Correct your athletes in practice if they yell the command too soon or too late. I ask my athletes to yell the command when they feel they are two arm lengths away from their teammate.

The timing of the handoff command is critical. I ask my athletes to yell the command when they feel they are two arm lengths away from their teammate, says @LFHStrack. Share on XAn important phrase to remember with blind handoffs is Command-Hand-Reach. This is the order of execution for the incoming runner:

- Yell the command.

- See the target hand.

- Reach with the baton.

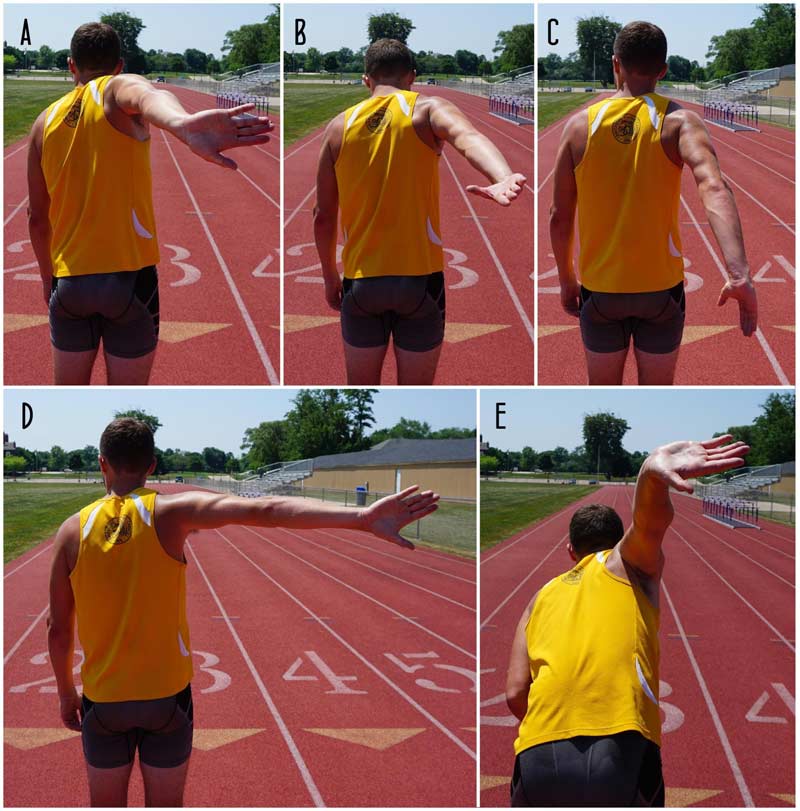

Too often, incoming runners reach before they see the target hand and sometimes before they even yell the command. It is so important for the incoming runner to see the target before reaching for it with the baton. For one, most runners naturally start slowing down a bit when they reach out with the baton. Keep the arms pumping to keep your speed up. Look at image 5 to see the incoming runner’s arms still pumping as the outgoing runner gives the target.

Reaching too soon increases the chance that the outgoing runner will knock the baton out of the incoming runner’s hand. So remember: Command-Hand-Reach!

Another option is silent exchanges. A common strategy is to have the outgoing runners take six steps and then throw their hands back.

There are positives and negatives to both the verbal and silent exchanges. Many coaches who swear by the silent exchanges tell me they are worried their outgoing runners will have to pick their teammate’s voice out of a crowd of eight athletes yelling Stick! at the same time. That may be a valid point, but in my 20 years of coaching track, I have never once had a kid tell me, “I couldn’t hear him say Stick!” If that ever did happen, maybe I would change my strategy, but for now, my athletes use verbal commands on blind handoffs.

It is also important to note the commands required if the outgoing runner takes off too early. You need these commands whether you are executing a verbal or silent exchange. Incoming runners who believe they will not catch their teammates should yell Slow! which, of course, means the outgoing runner should keep running but slow down. If the outgoing runner goes out way too early or the outgoing runner is almost at the end of the zone, the incoming runner should yell Stop!

Some coaches teach their outgoing runners to peek over their shoulder if they hear the command to slow or stop so they can gauge where their teammate is and execute a better exchange. While this certainly helps in many situations, one main problem is that athletes who peek over their shoulders will almost certainly move their target hand.

If you use open handoffs, you do not need to worry about commands. One benefit of open handoffs is that they limit the risk inherent in blind handoffs. Open handoffs are generally seen as slower than blind handoffs, but if you practice them consistently, the benefits can outweigh the negatives. Starting off too early or too fast can be death with blind handoffs but only requires a minor adjustment with open handoffs.

Video 3. Blind handoffs vs. open handoffs: The first handoff also shows a great example of Command-Hand-Reach.

Hand Placement

You can have the fastest athletes who follow lane discipline and take off at the right time, but that could all be for naught without proper hand placement. Regardless of which hand placement you pick, the main priority is to keep a steady target. A moving target is much harder to hit than a stationary target, so you want your outgoing runner to give a target that is steady and easy to see. Image 6 shows a variety of different hand placements.

The stop sign method (A) is the most desirable because of the large target it presents. Many athletes with lower joint flexibility may need to flex their elbows more than the athlete in image 6. Variations of the stop sign include D and E. Some coaches choose D because it is a more natural position—you can see the athlete is not as crunched up in his shoulders. However, I have found that because the shoulder in position D is not in a natural running position, the first few arm swings after the athlete receives the baton are less than ideal.

For position E, the athlete leans forward, which has two benefits: 1) many athletes are still accelerating at this point, which means they’re already leaning forward, and 2) the lean helps get the hand higher in the air, thus giving a better target.

Position B shows a flat hand, which feels more natural to most athletes than the stop sign. I have found that in the heat of the moment, many athletes forget about the stop sign and revert to the flat hand. Honestly, most athletes I have coached are most comfortable with the flat-hand method, and if it works, I don’t change it.

Position C shows underhand or upsweep passing. The benefit is that it most closely mimics proper sprint form. One negative is that the handoff is given lower, so you lose a few feet of space on each handoff because the athletes must be closer to each other to make a proper exchange. The second negative is that the runners gradually run out of room with their hands on the baton.

Of course, another option is to complete open handoffs, like a sped-up version of a 4x400m relay handoff.

Reach

The last aspect of the handoff is the act of the incoming runner placing the baton into the outgoing runner’s hand. While this may seem—and should be—incredibly simple, a great many botched handoffs occur exactly at this point.

Video 4. Brad Fortney and Carly Fehler demonstrate different reach techniques for the sprint relays, including the “push,” “flat,” “above,” and “swing” techniques. With very few exceptions, athletes should use the “push” technique (also called “candlestick”). In no instances should any athlete use the “above” or “swing” technique.

As mentioned in the Commands section, the incoming runner needs to follow Command-Hand-Reach. Give the command, see the target hand, then reach with the baton. Be sure to instruct your incoming runners to keep running at top speed until they have handed off the baton!

Perhaps the most important part of the reach is that the incoming runners must continue running at top speed until they have handed off the baton, says @LFHStrack. Share on XToo many runners consider their leg of the relay finished once they give the command, so they slow down when the baton is still in their hand. This can be disastrous, so you must constantly reinforce your athletes to run through the zone. This is explained more in Section VI: Run Through the Zone.

V. Practicing Handoffs

In my opinion, 4x200m relay handoffs are the hardest to practice. The 4x400m and 4x800m exchanges are slower and less technical and include exclusively open handoffs. The 4x100m is faster, but there is less of a fatigue factor, so as long as you are fresh while practicing them, race conditions are relatively easy to replicate. But with the 4x200m relay, it is very difficult to replicate in practice how fast an athlete will finish in a race.

There are two main issues we see in performing 4x200m relay handoffs in practice:

- The incoming runner will speed up if the outgoing runner is getting away from them.

- The incoming runner has trouble gauging their appropriate finishing race speed.

Let us tackle #1 first. Often, coaches instruct their incoming runners in practice to run in at 85% to simulate the fatigue at the end of a 200m race. So, the runner does as asked and runs it at a submaximal speed, but then the outgoing runner takes off a bit too soon and looks like they’re going to get away.

In this scenario, most of the incoming runners will then speed up to catch the outgoing runner. They are able to speed up because they are not running at full speed, but in an actual race, they will not be able to speed up! If athletes practice this way, they will not have successful handoffs in the race. If you practice handoffs by having the incoming runner going 85%, you must instruct that incoming runner to keep a consistent speed.

Regarding #2, many athletes seem to believe they will be running full speed at the end of a 200m race, so they run full speed in practice. Obviously, athletes are battling fatigue at the end of a 200m race and are not near their top speed. So, a solution for many coaches is to have the athletes simulate their finishing 200m speed by running submaximally at something like 85%. This is hard to estimate and can lead to the issue we discussed in the previous paragraph.

So, how do we fix these problems? How do we get our athletes to simulate their 200m finishing speed without actually having them run a full 200m in practice?

Burpees.

Yes, I know that burpees are the bane of many fitness experts. Hear me out. We need to simulate the finishing speed of a 200m in practice without actually cashing the athletes to that extent. I have found that having the athletes perform 6–10 burpees and then pick up the baton and sprint all out does a great job of simulating the correct speed.

I have found that having the athletes perform 6–10 burpees and then pick up the baton and sprint all out does a great job of simulating the correct speed, says @LFHStrack. Share on X

Video 4. The incoming runners perform eight burpees before attempting the handoff at top speed. This is a great low-cost way to simulate the approximate finishing speed of a 200m race.

The burpees appropriately fatigue the athletes in the short term without causing any lingering fatigue in the long term. This has the added benefit of putting pressure on the athletes to get it right since they certainly do not want to continue doing more burpees if they mess up the handoff.

Another strategy is to run a continuous relay, which can double as a submaximal workout. An example of this would be to set up the athletes in practice as if they are running an actual 4x200m relay. The athletes would then run the first 50 and last 50 meters of their leg at 100% while “floating” the middle 100 meters. This would appropriately fatigue the athletes for a handoff without having them go through the tax of an all-out 200-meter rep.

There are two strategies to ensure the athletes run the correct portions at top speed. One is to set out cones or markers for when each athlete needs to switch gears, and another is to have the coach blow their whistle when the gears need to be switched.

VI. Run Through the Zone

While running through the zone is incredibly important in every relay, it is perhaps most important in the 4x200m relay. This is due to two factors:

- The incoming runner is dealing with fatigue near the end of the race.

- The outgoing runner is catching a blind handoff.

While outgoing runners in the 4x400m and 4x800m relays look over their shoulder at the incoming runners and can, therefore, adjust their speed to compensate, the blind handoffs in the 4x200m make this difficult.

The cardinal sin of relay running is slowing down while still holding the baton. I preach this to my athletes dozens and dozens of times, yet I still see it quite a bit, often when athletes slow down after giving the Stick! command. The main issue is that the outgoing runner rapidly picks up speed at this point, so any slowing down by the incoming runner will almost certainly jeopardize the exchange. You have undoubtedly seen this with your athletes in the 4x100m, 4x200m, 4x400m, and even 4x800m.

The cardinal sin of relay running is slowing down while still holding the baton. I preach this to my athletes dozens and dozens of times, says @LFHStrack. Share on XYou need to emphasize this with your athletes every single day that you practice handoffs! Even if the handoff is successful, remind your athletes not to slow down in the zone.

A great way to emphasize running through the zone in practice is to have the incoming runners continue running at top speed even after they have handed off the baton. If you have multiple athletes doing handoffs at the same time, start the incoming runners all at the same mark at the same time (the hurdle marks work great). Let them know two races are going on: 1) the outgoing runner crossing the end of the exchange zone with the baton, and 2) the incoming runner crossing the end of the exchange zone. If you work on this early in the season, you should not have a problem with athletes failing to run through the zone in meets.

The two things I tell every member of my 4x200m relay team before every race are, “Leave on time and run through the zone.” If they all do that, we should be good.

A potential solution to this problem is to implement open handoffs, as covered several times in this article. Our 2022 4x200m relay at Lake Forest High School used open handoffs and qualified for the IHSA State Championships. We again implemented them in 2023, but the athletes talked me into switching back to blind handoffs for the Conference and Sectional meets. Everything went well at Conference, but we were disqualified for running out of the zone at Sectionals, which would have been unlikely with open handoffs.

VII. Indoor 4x200m

Call it a guilty pleasure, but I love the indoor 4x200m relay. What I mostly love is the chaos and the strategy. Indoor competitions are mostly about fun, and the indoor 4x200m relay is a lot of fun.

The key to winning the indoor 4x200m relay is getting the lead on the first leg. Passing on tight indoor tracks is very difficult, so your position after the cut-in will determine your position at the finish line over half the time. The team in fourth place has to hand off in lane four, which adds meters and confusion to the race.

Put your fastest guy on leadoff. If you know your fastest guy will only get you in about fourth place in the fast heat, seed yourself slow to get in a slower heat. Get the lead in that heat, and your time should be a lot faster than if you were in fourth place in the fast heat. This is gamesmanship, sure, but indoor meets are for fun. Gamesmanship is expected.

My second-best recommendation for the indoor 4x200m relay is to use open handoffs instead of blind handoffs. This is especially important on the third and fourth legs when athletes are not confined to their own lane. Despite the best intentions of the officials, many athletes line up in the wrong order.

The order for handoffs is determined as the athletes are on the backstretch, so the team in first place has their next athlete line up in lane 1, the team in second place lines up in lane 2, etc. However, many high school athletes just wander out there and stand wherever they feel like. Even if the athletes do line up correctly, the orders can change when runners pass each other. (This is difficult, but it happens.) In virtually every indoor 4x200m relay, you will have an athlete who lines up in the wrong place. This means at least one other team has to adjust. You need responsible, experienced athletes who can quickly adapt to the situation.

Before you get to the meet, find out if the race will use a two-turn, three-turn, or four-turn stagger (some even use an eight-turn stagger; lanes all the way!). In a two-turn or four-turn stagger, the athletes cut in on a curve. In a three-turn stagger, the athletes cut in on a straightaway. There is no standard, so contact the meet host ahead of time to find out and prepare your athletes.

VII. Conclusion

The 4x200m relay might not be one of the most glamorous events in track & field, but it counts for just as many points as every other relay, says @LFHStrack. Share on XThe 4x200m relay might not be one of the most glamorous events in track & field, but it counts for just as many points as every other relay. Treat it as an important event, work on the handoffs, run through the zone, and have fun!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF