Are we strong? It’s hard to determine progress if you don’t have anything to compare to. We must define what it means to be strong if we’re going to say whether we are or not.

Differentiating between larger and smaller bodies is also valuable. If a 160-pound male and a 200-pound male can both bench press 225 pounds, are they equally strong? Per relative strength, the 160-pounder is much stronger with a relative strength ratio of 1.4x BW compared to the 200-pounder, who is actually pretty weak for his size with a relative strength ratio of about 1.12x BW. Judging an athlete solely by the weight on the bar is not a fair or accurate measurement, because it doesn’t tell the full story.

Also, at a certain point we become strong enough. This means that solely increasing 1RM strength will not lead to any further on-field improvement (training transfer). Once this happens, the emphasis of training must shift toward methods that will directly transfer.

We need to define what ‘strong enough’ is and measure how close we are to achieving it. Using this information to drive programming decisions is really what matters, says @pbasilstrength. Share on XAgain, we need to define what “strong enough” is and measure how close we are to achieving it. Using this information to drive programming decisions is really what matters. Continuing to progress maxes for a team that doesn’t need them is a waste of time and a huge opportunity lost.

Strength Standards Defined

These standards are benchmarks I use to determine an athlete’s relative strength, which is the load they can handle well compared to their body weight, or how strong they are in certain movements or lifts. Usually, this is measured as their one rep max in the lift divided by their body weight. For example:

- 300-pound bench press at 220-pound body weight

- 300/220 = 1.36

This athlete can bench press 1.36x their body weight, which is really good for a male and insane for a female.

For other lifts, I’ll determine relative strength by a weight they can handle for a common amount of reps. I use this method for lifts we don’t test maxes for, such as:

- Barbell RDLs

- Lunges

- Neck work

I usually program RDLs between five and 10 reps and most commonly from six to eight reps. So, our standard for barbell RDLs is the weight they use for eight reps with flawless form and technique. These I don’t compare to body weight; just the load itself is the benchmark.

For other lifts, I’ll just make a mental note of the weights used by most athletes in the group and do some quick math in my head. Reverse lunges are an example of this. If my average baseball player weighs 180 pounds and most of them use 185 pounds for reverse lunges for 6-8 reps, that’s pretty solid. This means most of the team can reverse lunge their body weight for at least 6-8 quality reps. If that same group is only using 95 pounds, we need to work on strength in that movement. That information drives programming decisions: In the second case, more focus on improving strength in the lunge is required.

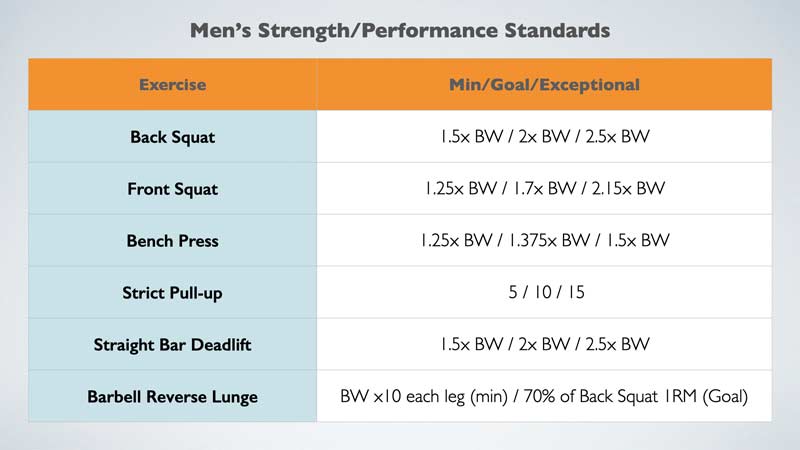

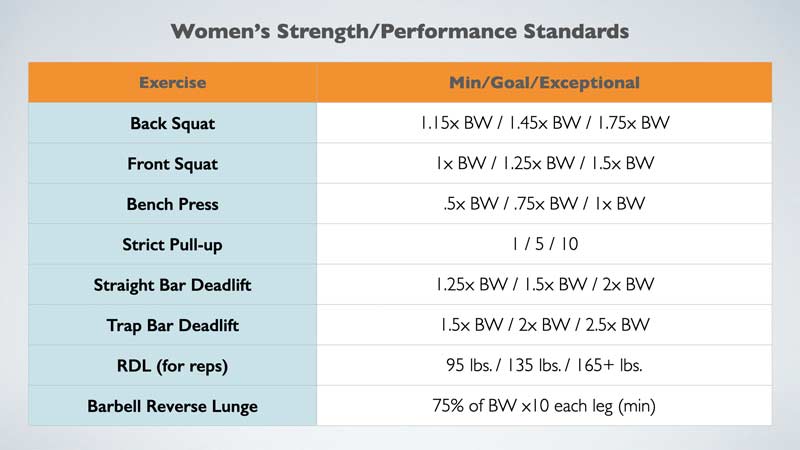

The strength standards I use for common main lifts are:

How Did I Come Up with These?

Some of these are accepted standards supported by evidence, some are long-held norms in the field, some I found in random articles, some we figured out just by watching what our beginner, intermediate, and advanced athletes do, and others are extrapolated by math.

The back squat standards are pretty common across the field. The front squat is about 80%-85% of the back squat, so the front squat standards are 20% less than the back squat standards. Understand they are benchmarks and measurements, not hard and fast gospel rules. Your experience may be different from mine.

How Do I Test Them?

We test major lifts throughout the off-season, usually at the end of the semester after we’ve been training the team or group consistently for 16 weeks. With some teams, we do work up to a true 1RM; for different groups we also use reps in reserve and estimate a max, and for others we just make a mental note of how much weight they use. RDLs, lunges, and the neck machine are all examples of this.

For testing, we work up to a true 1RM, use reps in reserve and estimate a max, or just make a mental note of how much weight they use, depending on the group, says @pbasilstrength. Share on XThis is actually becoming my preferred method of evaluating strength over set maxing and testing weeks. Yes, we do share these standards with them—our athletes are very driven by measurements (and grades), so they want to be able to hit each one and see how they stack up.

Using Standards to Dictate Training

What does the athlete or group need from their training? Are they strong enough, or do they just need to continue what they’re doing and get stronger? The team average in each movement allows you to determine that.

I often find groups are strong enough in certain lifts, but not others—male athletes tend to hit the trap bar and squat standards faster than the bench press standards. In this case, the training for lower-body movements may be shifted more toward dynamic effort and power emphasis, where upper body strength will continue to follow basic progressive overload and more repetition assistance work. You can be strong enough in one lift/movement but not another.

If you only have one team to train, you could also break them into different subgroups based on what they need. Large rosters, like football or swimming, will not all be at the same level. If it’s logistically possible, you could use these measurements to tailor training for different ability levels (see beginners, intermediates, and advanced athletes).

Beginners, Intermediates, and Advanced Trainees

Training age refers to how many years an individual has been training in a supervised setting, not their actual age. Training level or ability refers to the:

- Level of skill

- Movement quality in major movement patterns like the squat, hinge, and lunge

- Base level of strength demonstrated by athletes (usually compared to their body weight).

All athletes will fall into one of the three levels:

- Beginners (novices)

- Intermediates

- Advanced

Beginners

Beginners are exactly that. They have no real consistent experience training in a structured and supervised setting and do not possess any base level of strength, work capacity, or movement skill. Their training should reflect this.

Use the most basic variations of exercises that they can execute well with confidence. Apply minimal but consistent progressive overload and strive for continued quality movement. Strength, size, and power gains for this population will come simply by following that formula.

Beginners do not need advanced methods and likely will not be able to truly get the most out of more complex movements and methods anyway.

Intermediates

Intermediates are those with at least one to two years of direct and consistent training experience in a structured setting under a qualified coach. This population can execute basic variations of the major movement patterns well and can handle moderate training loads with consistent great technique and form, but they still have room to progress in gaining strength. They can hit the minimum strength standards but have not reached the point of diminishing returns for strength gains.

This population can begin to use heavier loads and more progressed exercise variations and learn more advanced methods. Training for this population should still be rooted in consistent movement quality, progressive overload, and simply continuing to get stronger and generally more explosive and powerful.

Advanced

Advanced groups are those athletes with at least three years of direct consistent experience under a qualified coach and who can move heavy training loads with flawless technique. This population can hit every strength standard goal and be considered “strong enough.” They have reached the point of diminishing returns to improving athletic performance solely by improving strength. Their training must be tailored toward increasing speed, power, and training transfer to the playing field for their sport. Individualization of the programming to improve weaknesses is also a great way to progress this population if it’s feasible with your logistics. I discuss training for advanced athletes like this further in my Advanced Training Manual.

Training for each level must be tailored accordingly (SAID principle). Beginners cannot execute to the same degree that advanced trainees do. Conversely, beginner training will not be a sufficient-enough stimulus for advanced populations. It’s your job as the coach to determine what level the group you are working with is currently at and tailor the training accordingly.

Beginners should be able to hit each movement’s ‘minimum.’ Intermediates should strive to hit each movement’s ‘goal.’ Once an athlete can hit the goal numbers, they’re considered to be strong enough. Share on XBeginners should be able to hit the “minimum” in each movement. Intermediates should strive to hit the “goal” for each movement. Once an athlete can hit the “goal” numbers, they’re considered to be strong enough.

Long-term training can really be simplified to this: Teach and develop movement mastery and quality, then work to reach the strength standards through progressive overload.

That will encompass anywhere from 90%-99% of the athletes you’ll work with. Strength is the lowest-hanging fruit in terms of improving performance and reducing injury risk; it’s also very easy to train. Follow that formula, and I truly believe you’ll cover about 90%-95% of all transfer from the weight room to the field. Once an athlete is “strong enough,” training becomes an ongoing pursuit of that last 5%-10% of improvement.

At this point, bridging the gap between developing strength and translating it to sporting action becomes the emphasis of training. Shifting emphasis in training from strength dominant to power and explosive strength dominant is one way to reach that last 5%-10%.

Considerations for Larger Bodies

There will always be outliers with measurements like this. Do I expect every 300-pound player to squat 600 pounds to hit 2x BW? That’s a tough ask, but 450 pounds to make 1.5x BW is certainly reasonable. If they’re more than 300 pounds, they’d better be strong. If you have a 280-pound lineman who can’t squat 225 pounds, put two and two together.

Tall athletes are the real outliers. Think 6’4” and up. It’s much more difficult for the 6’5” forwards to squat to depth than the 5’9” running backs. For very tall athletes, I compare them to similar-sized bodies. Though they should still be able to hit the strength minimums, just understand it’s a little more impressive for them. I’ve found that very long-limbed athletes need a much longer emphasis on just developing strength and movement quality than their shorter peers. Progressing them to the next step in training will take longer and is less of a priority.

Will These Standards Work with High School or Youth Athletes?

I developed these standards based on our college athlete population, but that’s not to say they won’t work at the high school level. I wouldn’t worry about measuring relative strength for that population until they have a full year of supervised training in your program. They will get stronger and improve just by training properly and consistently. This is really the case with untrained college freshmen, too.

That said, if you have high school upperclassmen who have been in your program for 2-3 years, they should at least be able to hit the minimum numbers. You probably have a few athletes in mind who can definitely hit these standards.

For youth athletes not yet in high school, I wouldn’t worry about testing at all. Just continue to improve movement quality and confidence and give them a great experience. If they enjoy training and do it consistently, the rest falls into place. That’s really the case at every level.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Coach Basil,

These are great and good job collecting some norms from the data. Where this falls short is RFD and the ability to produce the strength in a short amount of time. We are currently investigating this as part of our research in youth sports assessments. Too many are focusing on the 2.5xbw number. A slow grind 0.5m/s squat does not compare to a 1.2m/s squat and I can say from evidence, this number matters more. See recent studies by Danny Lum regrading this for evidence. The ability for an athlete to express their strength in a short amount of time carries over to the field much better than grinding out slow lifts. Great job getting to this point but there is a lot more to explore.

Great standards. So for males bench press, pull up (including bodyweight) and reverse lunge (barbell only or dumbell too?) should be roughly the same? Why Trap Bar Deadlift and RDL standards are only for females?