[mashshare]

Virtually everyone knows the importance of leg strength in pitchers. Training the lower half of the body usually focuses on the big movements like squats and deadlifts. They dominate the landscape for most athletes, and rightly so. When you look at a pitching motion, the majority of the actual motion from leg pickup to release is performed through an interplay of single leg motion. That interplay could fill a novel, but the main concept is that each leg individually plays an important role in pitching.

Before our athletes ever do a #deadlift, we teach and train the weighted barbell reverse lunge, says @ZachDechant. Share on XBuilding lower half strength with our younger athletes may deviate from the common thought. The reverse lunge is a staple in our program for incoming collegiate pitchers. Before our athletes ever dive into a deadlift, we teach and train the weighted barbell reverse lunge. Not only is it beneficial for creating strength in a split stance, but anecdotal and empirical research suggests it has a correlation to performance as well as injury prevention. For us, getting strong in a single leg movement outweighs the use of multiple double leg movements throughout a weekly mesocycle.

Performance and Lunge Strength Transfer

The first place to start with the lunge and its relationship to performance is to simply create more leg strength and motor control in the lower half. It has been well documented that leg strength can play a crucial factor in pitching velocity. The true transfer of a lunge movement to pitching is based upon several factors, with training age and the current level of the athlete potentially the most important. The lower the level of the athlete, the more transfer the lunge will have. As an athlete’s ability increases to a high or an elite level, you will find less transfer. Regardless, the lunge can be very beneficial along the path of development for many athletes.

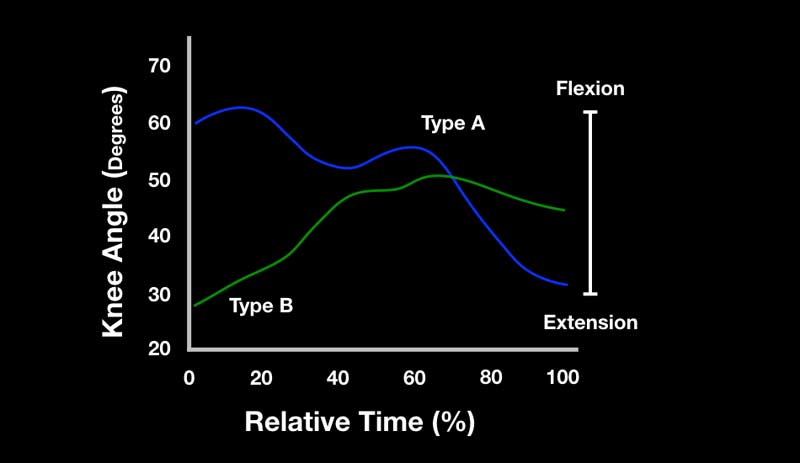

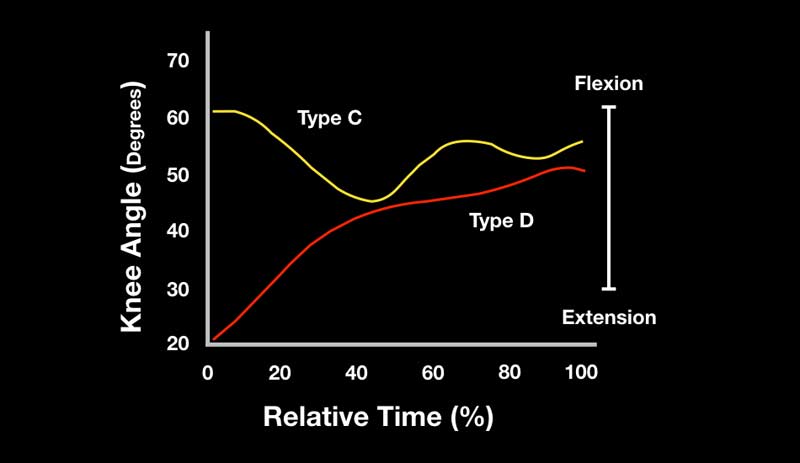

A study by Matsuo in 2001 documented four common patterns (A, B, C, D) in pitchers’ landing legs. Categorizing pitchers by either high velocity or low velocity, Matsuo found that the amount of flexion and/or extension of the front knee varied by how hard each group threw. He classified A and B patterns as more knee extension dominant, and C and D patterns as more flexion dominant.

Groups A and B landed flexed, but drove the knee back hard into extension at ball release. The C and D patterns essentially stayed flexed on the knee through ball release. The results showed that 83% of the high-velocity group displayed a front leg moving from flexion into extension over the course of front foot contact to ball release.

Another study done in 2015 by McNally showed that stride leg ground reaction forces were strongly correlated with ball velocity as well. While the study was done with 18 former competitive baseball players, the ability to decelerate on the front leg and apply force opposite the direction of the throw was significant.

Both studies illustrate the importance of the front leg and the ability to brace and apply force. Again, the athlete’s level matters here in terms of specificity, but building a large base of strength can clearly assist athletes.

Addressing Weaknesses

A new athlete entering a program cannot hide their weaknesses. One of the most common weaknesses that I find in incoming athletes is single leg strength. Many have rarely done anything in the realm of a single leg movement. If they have, it has often been solely with high-rep bodyweight lunges.

One of the most common weaknesses that I find in incoming athletes is single leg strength, says @ZachDechant. Share on XThere are many reasons that single leg work may be a weakness. One reason may simply be the time availability at the high school level. Many programs have limited time, and therefore coaches may choose to focus on large movements that athletes can do quickly. Single leg work may get lost in that mix or may not rank high enough on the scale of importance for the time available.

Athletes that do train in high school are often thrown into a one-size-fits-all basic program. Even if time is not an issue, programs are commonly built around the big basics such as squat and/or deadlift. Numbers are often important to coaches, and the reverse lunge isn’t a numbers lift. Therefore, it often gets looked over in the grand scheme of programming. Single leg movements aren’t sexy and don’t get the social media views that a big-time squat or deadlift does.

The Lumbar Spine

The prioritization of single leg movements over bilateral through our developmental phase is due to the large rise in back issues with incoming athletes. Pars fractures, and even disc injuries, dominate the landscape of high school/junior college baseball due to the high volume of skill work and low or nonexistent volume of training. Deficiencies in core strength and/or pelvic control, hip mobility issues, faulty movement patterns, and even the mechanics of how an athlete rotates all factor into the equation for a lumbar stress fracture.

Due to increased back issues w/ incoming athletes, we prioritize single leg movements over bilateral, says @ZachDechant. Share on XThe same muscles responsible for transferring rotational force through the body are also responsible for the deceleration of those same movements to protect the spine from injury. The spine undergoes large extension and rotation forces in any rotational movement. Athletes who cannot control end ranges of motion will end up ramming bony anatomy together while decelerating rotational movements. The result are stress fractures in the lumbar spine.

The first step is to eliminate movements that put large forces through the lumbar spine in the form of extension-based patterns. Squats, deadlifts, and RDLs are usually no-no’s for rehabilitating stress fractures. These bilateral movements often put athletes through large ranges of flexion and extension, and put huge forces through the vertebrae, causing once-dormant problems to again rear their head. Stress fractures that are asymptomatic will often stay hidden until they aren’t. If you want to find one, start putting athletes who are largely extended under load and see what happens.

Injury Prevention Benefits

The role of the kinetic chain in any rotational movement, especially that of pitching, cannot be overlooked. The legs, pelvis, and core all play fundamentally important roles in the buildup and transmission of energy. Weaknesses and/or breakdowns in the chain of a throwing athlete can transfer stress distally to the shoulder and elbow.

A 2013 study done by the Ben Hogan Sports Medicine clinic back found interesting results with UCL injuries and single leg testing. It looked at 60 baseball athletes, 30 healthy and 30 recently diagnosed with UCL tears. Players with UCL tears scored significantly lower on the Y Balance Test for both stance (P<.001) and lead (P<.001) lower extremities, compared to the non-injured athletes.

The Y Balance Test requires motor control of the lower half, transfer of body weight to each leg, core control, balance, and mobility to complete. The finished test looks for asymmetries. A deficiency in any of the above, or huge imbalances, could be a red flag for pitchers.

While you should view every study with a bit of skepticism, the findings of this data suggest there could be a potential association between impaired single leg ability and UCL tears in high school and collegiate baseball players.

Josh Heenan, strength coach, and president of Advanced Therapy and Performance in Omaha, Nebraska, has found similar results with the weighted reverse lunge. Based on data from more than 1,400 athletes, he and his colleagues view the reverse lunge as an important movement for pitchers for its correlation to velocity, as well as injury. They have created the “90mph formula” based on years of research with their athletes.

The formula is a roadmap, based on five training metrics, that they have found to be consistent with pitchers that can throw over 90 mph. Being strong in the reverse lunge is one metric in the formula. Those that do throw 90 mph or harder, yet can’t hit all the training metrics in the formula, are exponentially more prone to injury. While not published research yet, Josh and those at ATP have seen and shown the importance of the reverse lunge on lower body strength, and specifically on single leg strength in pitchers.

Progression to the Reverse Lunge

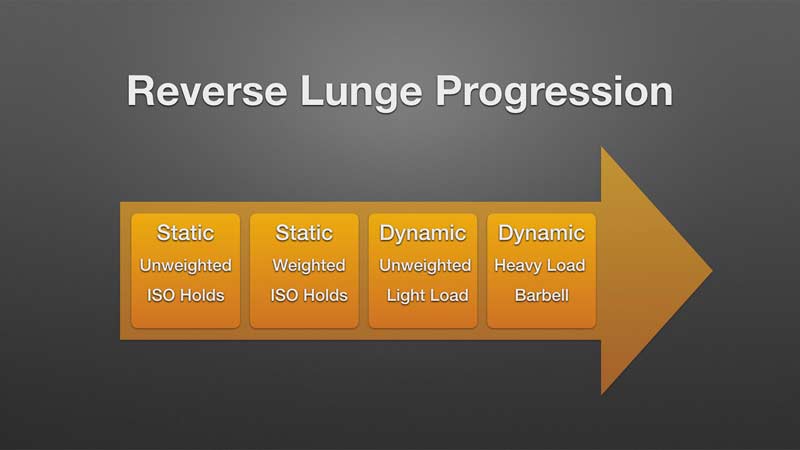

Progressing into the barbell reverse lunge often depends on the level of the athlete. The most common progression we take with our incoming athletes goes from static to dynamic. We work from unloaded to loaded through both those steps.

Static

- ISO Lunge – Unweighted

- The ISO lunge teaches body positioning and the creation of tension.

- Low-level athletes will start at 15 seconds each leg with a 10-second rest between legs. We add time over the course of the progression, up to 30 seconds.

- ISO Lunge – Weighted

- When the athlete can maintain 30 seconds, we add weight to the movement in the form of holding a plate in the front.

- Start back at 15 seconds each leg.

- Build to 30 seconds again.

- Note: You can use larger time frames here, but I find that 15- to 30-second sets fit well within the overall program as far as difficulty, ability to maintain posture, and training time are concerned.

- When the athlete can maintain 30 seconds, we add weight to the movement in the form of holding a plate in the front.

Dynamic

- Single Arm DB Reverse Lunge

- Athletes hold one DB in the hand opposite of their front leg.

- This achieves two things:

- Only holding one DB means a lighter overall load is used and movement efficacy can be prioritized.

- The single arm hold challenges the core musculature to a higher degree than holding two dumbbells does. It specifically emphasizes the all-important quadratus lumborum and obliques. Both are incredibly important muscles in back health and pelvic control.

- Reps are usually done in the 5-10 per leg range.

- Athletes perform all reps on one side before switching.

- Barbell Reverse Lunge

- We prefer the front squat variation.

- Athletes must be familiar with the front squat grip before undertaking this movement. The ability to hold the bar correctly sets up the rest of the entire movement.

- Athletes alternate lunges in this variation: Right leg then left leg until they complete all reps.

- Load the barbell up.

- Train this pattern to be strong.

- We prefer the front squat variation.

Just because athletes are performing a lunge movement doesn’t mean they can’t use low reps with high loads. Many coaches are nervous to train single leg patterns heavy with the barbell. In many cases they are right, as it is often difficult to maintain balance and/or dump a barbell if something goes wrong during the movement.

Just because athletes perform a #lunge movement doesn’t mean they can’t use low reps with high loads, says @ZachDechant. Share on XThat is one reason I prefer the front squat grip variation over the back squat. Holding and dumping the barbell becomes fairly easy and inconsequential when in front. The same can’t be said when the bar is on the back.

Parting Thoughts on Coaching the Reverse Lunge

Coaches also think of lunges as an assistance movement and pigeonhole it to be used only for higher reps and lighter weight. This couldn’t be further from the truth. The use of heavy loads has given us phenomenal gains in the past. Moving through the listed progressions wisely should set athletes up for success with the loaded barbell.

Athletes must show competence to use the weights early on. However, they will often shock you with how strong they really are in single leg patterns. It’s not uncommon for our pitchers, after a full training block, to reach upwards of 80-100% of their front squat max for heavy singles to triples on the reverse lunge.

Don’t be afraid to train with sets in the same zones as you would on other big compound movements, says @ZachDechant. Share on XDon’t be afraid to train with sets in the same zones as you would on other big compound movements. The use of one to five reps per side can be incredibly effective in building a big and strong lower half. Heavy reverse lunges can be an asset in any program.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Bohannon, Richard W., et al. “Relationship of Pelvic and Thigh Motions During Unilateral and Bilateral Hip Flexion.” Physical Therapy. 1985: 65(1); 1501–1504. doi:10.1093/ptj/65.10.1501

Garrison, J. Craig, et al. “Baseball Players Diagnosed with Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tears Demonstrate Decreased Balance Compared to Healthy Controls.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2013: 43(10); 752-758. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.4680

MacWilliams, Bruce A., et al. “Characteristic Ground-Reaction Forces in Baseball Pitching.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1998: 26(1); 66–71. doi:10.1177/03635465980260014101

Matsuo, T., et al. “Comparison of kinematic and temporal parameters between different pitch velocity groups.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 2001: 17(1); 1-13.

McNally, Michael P., et al. “Stride Leg Ground Reaction Forces Predict Throwing Velocity in Adult Recreational Baseball Pitchers.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2015: 29(10); 2708–2715. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000000937