One of my favorite things about this field is when really good coaches can boil down big, complex topics into simple, digestible phrases. For me, Eric Cressey’s summary of shoulder care was a lightbulb moment: shoulder care is about “keeping the ball on the socket.”

At the end of the day, the ball of the humerus has to stay on the socket of the scapula, making the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint. With all the stresses we put on the shoulder in overhead sports, how do we prepare the shoulder joint to maintain its integrity (ball on socket) as best as possible for as long as possible?

“Overhead athletes” as a category includes baseball, softball, volleyball, and tennis players, football quarterbacks, and swimmers, to name just a few. Since most of my experience has been with baseball athletes, that’s the lens I’ll use to frame this article. Still, it’s 100% worth mentioning that I’ve applied all of these concepts to my swimmers and believe that effort positively affected their shoulder health.

With this simple yet universal idea of “keeping the ball on the socket,” we must understand the throwing motion and all the demands it puts on the shoulder joint that threaten joint integrity. The two most demanding actions are layback (max external rotation) and ball release (shoulder protraction and upward rotation), where the most eccentric stress happens. That just means when the arm switches muscle actions quickly, first going from cocking the arm to accelerating the baseball forward, and second from baseball release to decelerating the arm. (This can also apply to hitting a volleyball or serving a tennis ball.) These forces make the arm want to fly off the shoulder, and we need to prepare the muscles not to let that happen, or “keep the ball on the socket.”

However, it’s important to keep in mind that throwing is a total-body motion and involves the kinetic chain, with ground reaction forces going up the leg, to the hips, through the torso, to the ball, and finishing through the arm. Additionally, the scapula (half of the shoulder joint) will largely dictate what the arm (humerus) is able to do.

Let’s view this ‘shoulder care’ topic as a total body puzzle that requires good scapular movement and strength of the rotator cuff through both specific and large ranges of motion, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XUltimately, throwing uses the entire kinetic chain—so whatever certain joints can’t do that is required to throw, different areas of the body will compensate to figure it out/make it happen. And likewise, whatever the scapulae can’t do, the humerus will try to figure out on its own. So, let’s view this “shoulder care” topic as a total body puzzle that requires good scapular movement and strength of the rotator cuff (four muscles largely involved with ball-on-socket stability) through both specific and large ranges of motion.

In this article, I’ll take you through my framework of organizing and programming shoulder care exercises. Before moving on, I want to give a huge shoutout to Eric Cressey for everything he has done for this field. Personally, I’ve slowly accumulated the majority of my knowledge on this topic through being a fan and consumer of his content over the last 7+ years. Although this is my interpretation and application of his information, it wouldn’t be possible without a solid foundation first.

Video 1. This will help illustrate the concepts below, including almost all of the specific exercises. This is a very visual topic in nature, so please reference the video as needed to understand the content fully.

Exercise Categories

(at 0:18 in video, with video examples at 2:52)

Not all shoulder care drills are created equal. Some require external load, some use partner resistance, some are held for a long period, some are perturbations to build proprioception, some are meant for off-season development, and some are better suited for in-season training.

Although the concepts below are universal, not every type of exercise listed below will 100% cover all the possible exercises you can do. This is just a place to start building your exercise library and understanding the variables that underpin exercise progression, as these categories are listed in mostly progression order.

End-Range-of-Motion Isometric Holds

Although we live most of our lives in the middle of most joints’ range of motion, injuries often happen when we take those joints to the extreme ranges of motion where they’re weakest. Athletes are sometimes required to be in these end ranges of motion, which often include a lot of force and a time constraint (e.g., acting fast to complete a play). So, the joint has to be strong in a weak position and still have time to stabilize or perform the action.

End-range-of-motion isometric holds are great for building some time under tension in those relatively weak positions, as well as improving the range of motion in that joint. This type of drill makes sense in the early off-season to start building capacity and strength in those joints. Progressions include longer holds or adding a weight.

Controlled Articular Rotations

Building on the end-range-of-motion isometric holds above, controlled articular rotations apply the same logic but are for the entire joint, not just a singular joint action. This mostly applies to joints with the largest range of motion: the hips, shoulders, and the scapulothoracic joint. In a slow and measured manner, controlled articular rotations take that joint through the largest range of motion possible, really using the muscles to find the extreme ranges of motion.

CARS make the most sense in the early off-season to build capacity and strength in those joints and a greater range of motion. Additionally, you can apply these drills in any warm-up (in a lower rep fashion) to thoroughly warm up the joint or as an active recovery workout to restore potentially lost range of motion in that joint. Progressions can be adding a weight or simply just achieving a large range of motion.

Concentric Raises

This is probably what most people think of when they think of a rep of an exercise: an entire rep of both the up and down, controlled the whole time but not focusing on a specific phase. What most people don’t understand is that concentric muscle action is the weakest part of the muscle action compared to eccentric and isometric muscle actions. Raises work well as a simple way to groove that movement pattern through a full range of motion and for a moderate to large number of reps.

What most people don’t understand is that concentric muscle action is the weakest part of the muscle action compared to eccentric and isometric muscle actions, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XRhythmic Stabilizations

There’s a much-repeated quote from Bruce Lee I’ll use to illustrate the challenge of training for sport: “I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.” Well, that’s not exactly how sport is played. I’m not one to critique a legend, but it’s an interesting concept to play off. In sport, there’s a lot of unpredictability within practicing and performing relatively the same movements.

Video 1. A snippet of two rhythmic stabilization shoulder care drills where the partner taps the athlete’s arm while they try to resist the motion.

Pitching would be a “closed chain” movement where the athlete initiates the movement on their own and doesn’t have to react, allowing them to practice the same throw 10,000 times. However, pitchers have multiple pitches; they must react and throw while playing defense, their rhythm and timing can get messed up when they’re paying attention to runners on base, and so on. Therefore, they need their throwing muscles, the entire kinetic chain, to be strong and safe in a variety of positions.

Hitting and defense would be an “open chain” movement where the athlete has to react to the pitch, the batted ball, etc.—basically, no swing or defensive movement is exactly the same. So, the entire kinetic chain for both rotation in swinging and running on defense has to be strong and safe in a variety of positions.

Moral of the story: as a performance coach, I’m here to make athletes and not “baseball players.” I need to prepare my athletes for all of the unpredictable elements of sport, including all the joints (shoulder, hips, scapulothoracic, etc.) and muscle actions required to be ready and durable to handle that.

Rhythmic stabilizations are unpredictable, partner-administered perturbations to a joint in a specific position. In other words, the partner applies taps in a random pattern of both timing and force to try to move the body part/joint out of position while the athlete tries to stay still, fighting the taps.

Rhythmic stabilizations are great for developing the proprioception of muscles to react to the unpredictable movement demands placed on them in sports, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XThis type of drill is great for developing the proprioception of muscles to react to the unpredictable movement demands placed on them in sports. The athlete needs to be strong and stable within all the various positions in the moment from the partner perturbations. These drills make the most sense in active recovery and in the middle of the off-season as a progression of isometric holds.

Eccentrics – Both Submaximal and Supramaximal (Partner-Assisted)

Eccentric muscle actions occur when the muscles actively lengthen and the joint angle of the muscles involved increases. Think about lowering the weight during a bicep curl or controlling the descent on a squat. This type of muscle action is used in every throw, every swing, and every stride in sprinting, most often when deceleration happens in that movement.

Also, eccentric muscle actions are when muscles can produce the most force and, consequently, develop the most strength. It’s a great challenge to maintain posture and joint positioning while controlling eccentric muscle action, especially with maximal intent. Within eccentrics, there are two main types:

- Yielding eccentrics are at submaximal intensity; think about yielding like a squat you can control on the way down for a specific duration (like four seconds), then squat it back up.

- Supramaximal eccentrics are with forces above an athlete’s muscles’ capabilities to isometrically or concentrically resist the force; think about supramaximal like a squat heavier than a one-rep max that you can only control going down but can’t hold at the bottom or squat back up.

Submaximal eccentrics make sense in the middle of a training program to progress from isometric holds, and supramaximal eccentrics make sense at the end of a program as the most forceful and challenging type of drill your athletes can do.

I listed these exercise categories from simple to complex and in an order pretty similar to how I’d progress them in a program. As I get into the shoulder-specific categories below, try to envision how the categories above apply to create a structured and logical progression of exercises.

Shoulder Care Categories

(at 1:40 in the video, with considerations at 9:05)

External Rotation

As mentioned earlier, max external rotation is very demanding on the shoulder joint. This happens as the torso and shoulder start to rotate forward while the arm and hand move backward, creating a lot of eccentric stress and whip-reversing the momentum of the baseball/arm.

Also, a big lightbulb for me from Eric Cressey is that during external rotation of the shoulder joint, the ball of the humerus wants to also glide forward (which can cause irritation in the front of the shoulder). So, the primary purpose of external rotation drills is to strengthen the rotator cuff in positions of shoulder abduction and external rotation (elbow up at 90 degrees at the side of the body).

Drills and Examples

- Prone external rotation lift-offs.

- Chest-supported external rotations.

- TRX external rotation holds.

- Banded external rotation walk-outs.

- Half-kneeling ER banded press and raises.

- Half-kneeling shoulder external rotation partner stabilizations.

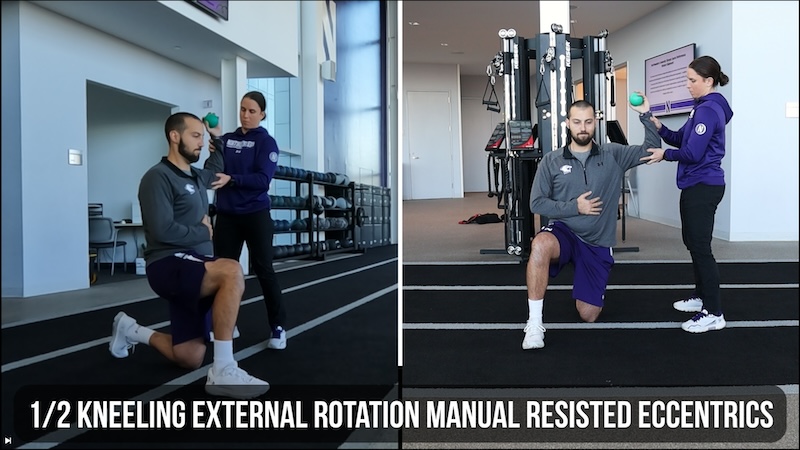

- Half-kneeling shoulder external rotation manual eccentrics.

Video 2: A snippet of some considerations to keep in mind when programming your shoulder external rotation drills to make sure you’re working the correct muscles and the exercises make sense in the big picture of the training week.

Considerations

I like to save my external rotation exercises for the last day of the training week. It makes sense to me that the rotator cuff is extremely important to keep the shoulder joint stable during throwing, so I need it as fresh as possible during the week. Then, on the training week’s last day, I can really fatigue those muscles of my athletes with upcoming rest the next few days.

Additionally, it is important to avoid “forward dumping” of the ball of the shoulder, which can cause pinching in the front of the shoulder. Be conscious of keeping the ball of the shoulder square in the middle of the shoulder joint.

Posterior Tilt

The posterior tilt is probably one of the most underappreciated movements that the scapulothoracic joint (scapulae on the rib cage) needs to do well. Think about this in a classic shoulder “Y” position: for the arms to go both above and behind the athlete’s head, the top of the scapulae needs to move backward while the bottom stays still. Good posterior tilt will help the athlete achieve better external rotation at layback. One of the main muscles helping to perform this action is the lower trapezius, so what I call a “Y raise” others may call a “low trap raise.”

The posterior tilt is probably one of the most underappreciated movements that the scapulothoracic joint (scapulae on the rib cage) needs to do well, says @CoachBigToe. Share on X

Drills and Examples

- Chest-supported Y raises.

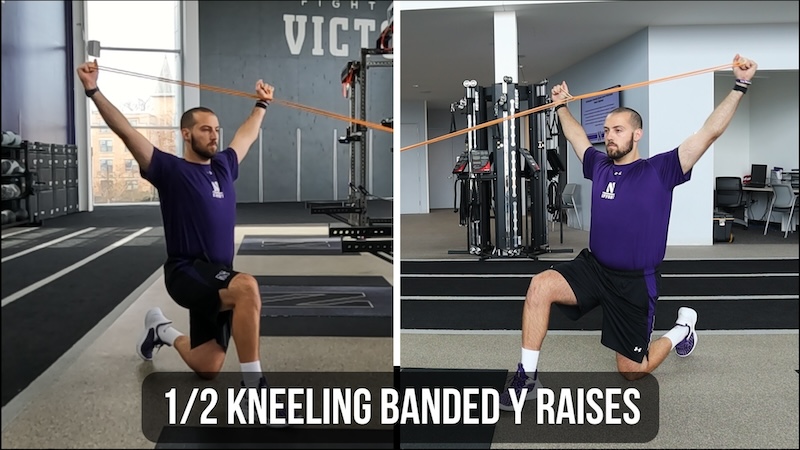

- Banded half-kneeling Y raises.

- Banded Y walk-outs.

- TRX Y holds.

- TRX Y eccentrics.

- Chest-supported shoulder Y stabilizations.

Considerations

There are many muscles that work on the shoulder and scapulothoracic joint, but we need to keep the main ones doing their job when working on specific movements. There’s a lot of overlap in muscle attachments and functions; with 17 muscles that attach to the scapulae for eight main movements, understanding what muscles we don’t want working is just as valuable as understanding which ones we do.

The upper trapezius (probably what most people think of as the “trap” muscle) also helps elevate the shoulder blade, but we need that muscle to stay off during our Y exercises. On the flip side, the lats helps bring the shoulder blade down so that muscle needs to relax to let the arm go overhead.

Protraction/Upward Rotation

I understand the concern about not wanting to overdo overhead exercises because the athletes are in that position so much during sport, but I’d argue that completely ignoring these exercises for that reason does more harm than good. It’s important to expose them to overhead positions and challenge their ability to be strong and stable in them, developing the muscles they’ll use when they go overhead in sports. Remember, it’s not the poison itself that’ll get you (the exercise); it’s the dose (how much).

Remember, it’s not the poison itself that’ll get you (the exercise); it’s the dose (how much), says @CoachBigToe. Share on XAs mentioned earlier, the scapulae function will dictate the arm’s ability to go overhead in a healthy and sustainable way. Again, from Eric Cressey, we need the scapulae to be able to “reach, round, and rotate” about the rib cage; round means protraction (the opposite of pinching your shoulder blades, so it looks like rounding your back), and rotate means upward rotation. The main muscle for this movement will be the serratus anterior, helping bring the shoulder blades from behind the body to in front around the rib cage.

Drills and Examples

- Banded cat-cow.

- Banded cat-cow walk-outs.

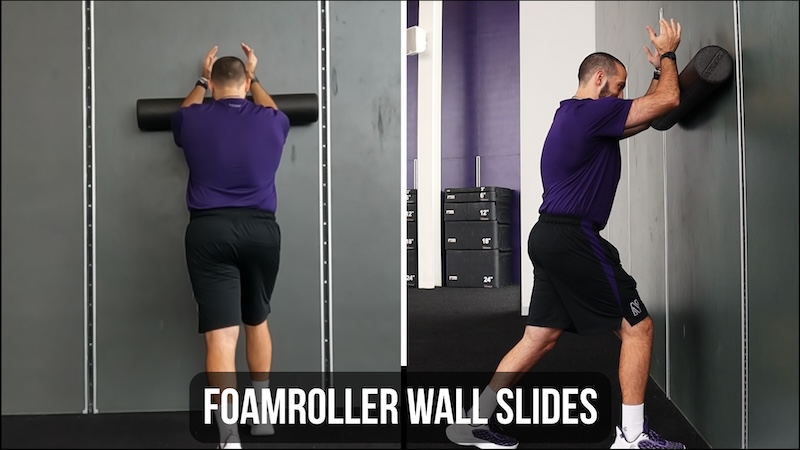

- Foam roller wall slides.

- Pike position holds.

- Push-up position to opposite toe touch.

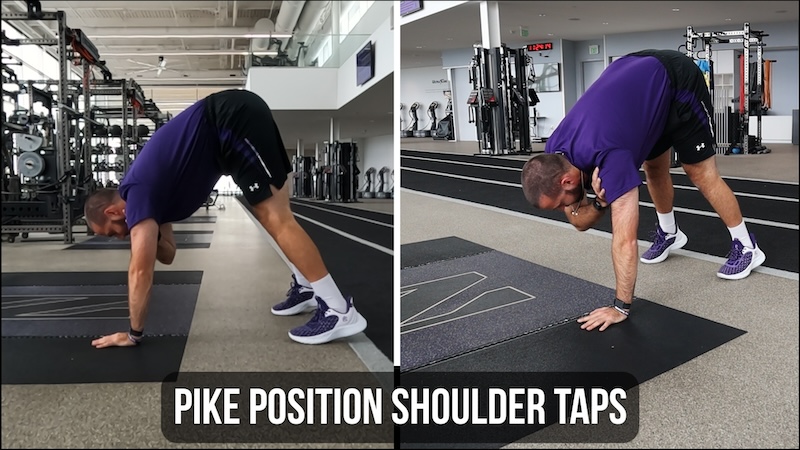

- Pike position shoulder taps.

- Pike position inchworms.

- Backward pike position walking.

Considerations

As listed above for our posterior tilt exercises, we need the right muscles to do the right job. Keeping big muscles like the upper trap and lats off allows smaller muscles like the serratus anterior to function correctly. This, in turn, creates good movement habits, which increases the longevity of athletes going overhead.

Thoracic Spine (T-Spine)

The first of the two categories that doesn’t (directly) involve the shoulder is the thoracic spine. As stated above, the thoracic spine is extremely important to help the scapulae work as effectively as possible (scapulothoracic joint); this, in turn, will help the arm move more efficiently. The thoracic spine—or the middle 12 vertebrae of the spine, each of which has ribs attached—needs to flex/extend and rotate.

Being able to extend the thoracic spine will help with getting the shoulder into external rotation at layback and flexion, which helps get the arm in front of the body for ball release. Lastly, rotation of the thoracic spine helps with hip-shoulder separation, which is imperative for an effective kinetic chain when throwing.

Drills and Examples

- Side-lying t-spine windmills.

- Quadruped t-spine openers.

- Seated twist-bend-breathes (which I shamelessly stole from the Titleist Performance Institute).

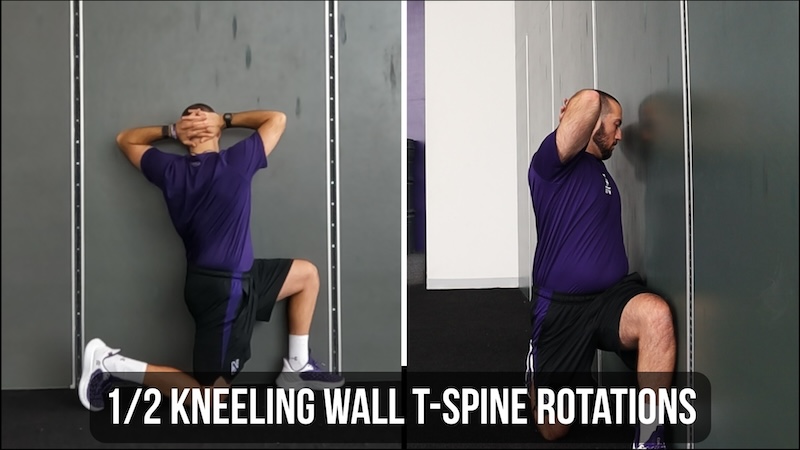

- Half-kneeling wall rotations.

Considerations

The t-spine has to function in a variety of different pressures, if you will. The athlete has to stay smooth and fluid, getting into a good attacking position (like before spiking a volleyball or layback in a baseball throw). But then the athlete needs to switch into propulsion by creating pressure and accelerating the arm/ball forward. The breath will be very important—exhaling to be relaxed to allow new ranges of motion and also inhaling to force the ribs to expand in that new range of motion. I coach my athletes to breathe out while getting into the end range of motion and to breathe in to create a new range of motion.

Additionally, the exercises mentioned above are mainly for t-spine rotation, while mobile and adequate flexion and extension are also required of the t-spine for overhead athletes. However, many protraction/upward rotation exercises also work on the flexion/extension of the t-spine.

Hips

The second category that doesn’t involve the shoulder is the hips. The case for this category is extremely similar to the thoracic spine; working up the kinetic chain, the hips need to internally rotate, externally rotate, and extend for effective rotation to get up the rest of the body.

What the hips can’t do will either lead to decreased rotation effectiveness (less velocity) or cause other joints up the kinetic chain to compensate and do things they weren’t made to do. Share on XWhat the hips can’t do will either lead to decreased rotation effectiveness (less velocity) or cause other joints up the kinetic chain to compensate and do things they weren’t made to do. What the hips can’t do will also lead to the lumbar spine compensating, then the thoracic spine, then the scapulae, then the shoulder joint, and so on.

Drills and Examples

- Hip 90/90 internal and external rotation lift-offs.

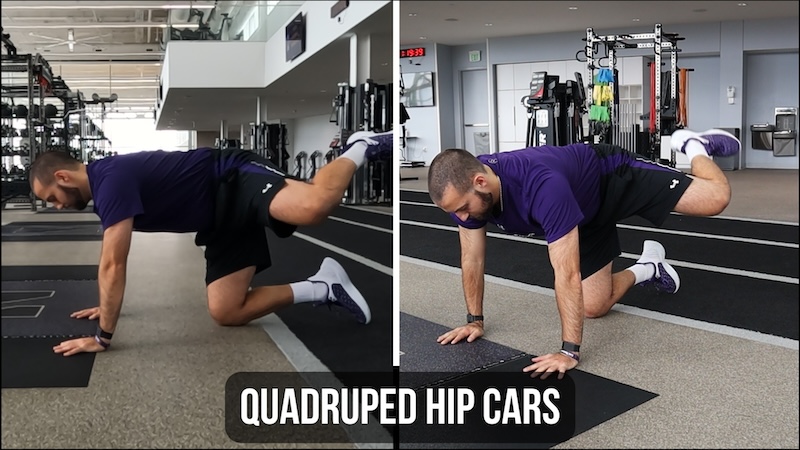

- Quadruped hip CARS.

- Rack-supported standing hip CARS.

- Hip 90/90 heel taps.

- Hip 90/90 switches (no hands).

Considerations

When working on very specific movements and joint actions, it’s very easy for compensations and other muscles to take over. It’s important not to rush through these exercises and to be conscious of minimizing movement of the rest of the body.

Other

Not every shoulder care category and drill will fit cleanly in an exercise category. Here are two drills I like, both controlled articular rotations, that don’t have a clear shoulder care category.

Programming Shoulder Care Exercises

From all the information above, the real challenge remains: how do we organize these exercises within a week to develop those muscles in training without increasing the risk of injury or taking away from the ability to play the sport itself at a high level due to excessive fatigue? These muscles are used for multiple hours a day in practice with every throw and swing, so we must be conscious about not overdoing it.

With that being said, there’s truly no right or wrong when programming these exercises as long as you have logic and justification for making the choices you make.

I recommend supersetting these exercises with non-competing muscle groups/exercises. As weird as it might sound, shoulder care exercises work great to program on lower-body days. For example, after hitting a heavy set of squats, would pairing hip-controlled articular rotations help or hurt the next set of squats? I’d argue that it would hurt, as those hip muscles need as much recovery as possible to keep the main thing the main thing (squatting heavy). Pairing a squat with a shoulder external rotation or protraction exercise would make more sense, as those muscles aren’t used during a squat.

Additionally, if your programs are already tight on time and maximized for efficiency of more primary exercise selection, you can easily add these exercises into a warm-up or cool-down as a not-very-time-intensive way to build frequency and exposure to these exercises. These can also be added to active recovery/mobility circuits on off-days.

As there’s no perfect program, I believe it’s also valuable to discuss when not to perform these exercises. I am a believer in following a high-low training model, basically trying to consolidate your stress to make your hard days hard and light days light.

With this in mind, I would consider a big pitching outing—for example, more than 100 pitches—a very stressful event for the arm and body. Consequently, post-game probably should not include these exercises. But on the flip side, a medium-sized outing—like 40 pitches—might warrant performing some of the more stressful exercises if the coach says the athlete won’t pitch the next day. These exercises are used to turn a “medium” intensity day into a “high” intensity day, setting them up for a nice recovery day the next day. Additionally, exercises like controlled articular rotations would fit very well in an active recovery mobility circuit, aiming to regain lost range of motion the day after pitching.

Is this to say this article includes every exercise, variation, type, and category of shoulder care?

Absolutely not. Will every drill fit cleanly into one of these categories? Nope. Are there exercises I’m learning and experimenting with that will grow my arsenal every week? Absolutely.

What I outlined here is what works for me with my athletes, both efficiently and effectively for my coaching/programming style and having 35+ athletes in the facility I train at. But what I hope for you is that this article gives you a framework and starting point to organize your thoughts and help you write your programs more efficiently. These principles and concepts are universal in training and programming, but seeing some of the structure and thought processes behind them might just be what you need to take your shoulder care to the next level.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF