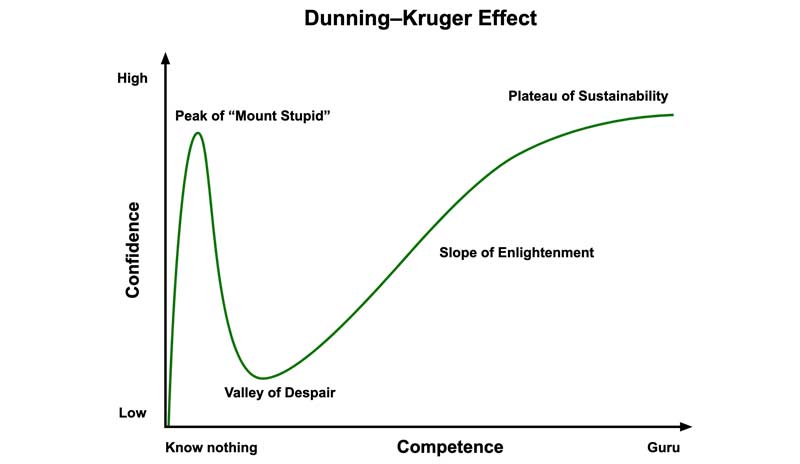

If I had to pick one concept from psychology to summarize coaching development, it would be the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Although that might come off as a little cliché, if you experience it firsthand, you will realize why it’s so commonly used. In popular terms, the concept traces a progression where:

- When you first learn about something, you’re excited and feel like you know everything because your knowledge on that topic just exponentially increased (the Peak of “Mount Stupid”).

- Then you become aware of the vastness and depth of that topic, which causes you to feel like you know nothing (Valley of Despair).

- You embark on a long, slow journey of increased knowledge (Slope of Enlightenment).

For me, year one of full-time coaching was definitely the Peak of “Mount Stupid,” with year two being the Valley of Despair and year three marking the ascent out of those depths and beginning up the Slope of Enlightenment. And what moved me forward through these peaks and valleys were the hours and hours and hours…and then even more hours, all just coaching—coaching kids as young as nine years old up to professional athletes and working with those whose goals range from becoming a pro athlete to making the high school team to just wanting fitness as part of their weekly routine. And doing so in settings ranging from a one-on-one with an athlete all the way to 100+ athletes I met just five minutes prior.

Starting my (hopefully) graceful rise after falling off the peak of Mount Stupid, I want to share the three biggest mistakes I’ve made and, consequently, what I’ve learned. Hopefully, I can expedite your learning process just a little bit as I start my long climb up the Slope of Enlightenment.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=14424]

Mistake #1: Thinking I Had Enough Stories from Just One Year of Coaching

The one story that marks the beginning of my descent from Mount Stupid—and that will forever make me cringe every time I think about it—comes from a phone call I had after only a few part-time summers and a graduate assistantship under my belt…

I connected with an extremely well-known coach in the speed development space, someone I followed for a while and who made a significant impact on my and my coworker’s training philosophies. We scheduled a phone call, and I was an eager combination of nervous and excited. That phone call finished in about 27 minutes but felt like an eternity…the conversation was stale; it was just me asking questions and interviewing them with no real back-and-forth. I felt like I completely blew my one opportunity, which caused me to lose more sleep that night than it probably should have.

As time heals all wounds, I reflected on that phone call and realized that at that point in my coaching career, I just didn’t have enough stories, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XAs time heals all wounds, I reflected on that phone call and realized that at that point in my coaching career, I just didn’t have enough stories. We could replace the word stories with experience, but you’ll see why stories makes more sense with my examples below. Stories allow you to do two main things:

Contribute to Conversation

I’ve connected with more coaches over the last three years—both intentionally and unintentionally networking—than most coaches probably will in their whole career. Many of those calls I planned to be 45 minutes long instead lasted three hours. This is because the other person had a background and interests similar to mine, the anecdotes we shared we both found interesting and fit well together, and so on. The conversation flowed, and I felt we connected more deeply than with the typical phone call.

On the flip side, I’ve also had phone calls I planned on lasting 45 minutes that ended up being barely 30 (like the one I shared above), and even those I initiated, I couldn’t wait just to finish. During those calls, the other coach and I didn’t really have anything in common, and I brought nothing to the table besides my questions from stalking them on the internet beforehand.

With that being said, I’m pleased to announce that the success rate of all my networking phone calls is dramatically higher in year three than in year one for one simple reason: I have more stories. I can contribute to the conversation by sharing interesting anecdotes, opinions, and insights to make it more of a back-and-forth than an interview. I can provide value to the other person with my unique experiences that can help them learn and grow instead of me just taking information from them.

Demonstrate Expertise

Although this story is from grad school, you’ll still learn from my embarrassment… It was the beginning of the second year of my master’s program, and because I knew graduation was inevitable, I started applying for jobs. Come October, I get a response from an application to schedule an interview with a professional baseball team. I learned who would be on the Zoom call, researched their backgrounds, and prepared notes for what I assumed they’d ask me relative to my experience and that role.

I had some experience, including a few part-time summers coaching and one semester of doing collegiate sports science, but that was pretty much it. My notes consisted of definitions of concepts from my textbooks and research studies I read in class. Once I finished my preparation, I had this feeling in my gut that it wouldn’t go well…and the interview turned out predictable and boring, like something was missing. And in retrospect, I know what it was: real-life stories.

Fast-forward 3 1/2 years, and I was interviewing again with a professional baseball team. The opening question of the interview was, “Tell me about a time you optimized the data reporting process.” I said, “I actually used to send Excel documents every day to the coaches with the athletes’ wellness data. Then I realized we only met weekly and made decisions based on the week, so why was I sending daily data? I changed to just having reports for the meetings but was ready to answer any questions they had between meetings. The coaches told me they felt less overwhelmed with one report per week instead of seven and were actually excited to see the data as it aligned more with their decision-making processes. As all sports science follows a data-discussion-decision flow, we needed to look at what decisions and at what frequency we wanted to make them, then work backward from there.” I received incredibly positive feedback about that answer, which definitely was not something I could’ve said 3 1/2 years earlier.

Everything in performance is a shade of gray, so when ‘it depends’ is the correct answer, you’ll have stories to turn that into ‘it depends, and here’s why,’ says @CoachBigToe. Share on XWithin stories is the opportunity to discuss nuance. Everything in performance is a shade of gray instead of black and white, so when “it depends” is the correct answer, you’ll have stories to turn that into “it depends, and here’s why (insert story).”

Lesson: Stories matter, and you need a lot of them.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9056]

Mistake #2: Believing What I Put on Paper Is What Causes Improvement

The first year of full-time coaching is a blur; everything’s new and exciting due to the exponential learning rate. And this story takes place during my second year, right when coaching started to slow down in my mind as I felt more comfortable and collected. I had both my largest group and longest-training group so far…

It was the fall, and I was training a group of 12 sophomore high school baseball players. They were all friends; they worked and competed hard; everyone involved enjoyed a great experience. The group doubled their initial six weeks and were with me for 12 total weeks. The fall then ended, and it was time for winter training to pick up in anticipation of tryouts, with much of the group being varsity hopefuls. However, three athletes of the group decided to continue training until tryouts for another six weeks.

Finally, tryouts came and passed, and the athletes/parents relayed the good news about making the team with very positive feedback about the training and the results it created. However, a theme appeared from those texts, with some being much more satisfied with the results than others…it wasn’t the ones who worked the hardest or the ones I wrote a special secret program for. It was the three athletes who continued training and were with me the longest.

Programming on paper feels great. It’s systematic, objective, and easy to say, “We did more than last time.” However, as you’ll learn with coaching more and more sessions, rarely does it go 100% as planned. Athletes come in a little beat up from practice, some miss sessions with outside injuries, and sometimes a long day of school completely destroys all their focus for the day. So being able to take a step back and ask, “What is the least I have to do today to cause improvement (minimal effective dose)?” and “How do I get my athletes to do that for as long as possible?” creates a long-term mindset that sets up both you and your athletes for the most success.

There are plenty of other examples I could share about athletes not setting PRs all summer, then they go on vacation for a week or two and finally PR because they’re actually recovered, or athletes leaving for 3–4 months then hitting PRs because puberty just gave them a little more size and strength…but I don’t want to run this point into the ground. Just understand that what you put on paper is the minimum for good training, so focus on the intangibles, like the environment you create and the relationships you develop to ensure that training becomes long-term.

What you put on paper is the minimum for good training, so focus on the intangibles, like the environment you create and the relationships you develop to ensure that training becomes long-term. Share on XLesson: What really causes change is good, fundamental training done over a long period.

Mistake #3: Believing My Athletes’ Expectations About Training Will Always Align with Mine

There was a high school athlete who had trained with me for well over a year, during which time I got to know him pretty well. His priority was definitely to enjoy himself but also to work hard when the time came. I was skeptical about his big plan and athletic goals, but hey, it’s his life to live and not mine.

His goals changed from making the high school baseball team to just wanting to work out consistently, and one day his energy was lower than usual, and he wasn’t talking as much. The workout had an incredibly slow pace, and I started to get paranoid that we wouldn’t get through the training, which would cause him and his parents to feel like they didn’t get their money’s worth.

Long story short, this athlete just went through a breakup, so we ended up sitting and talking for 30 minutes. I was still paranoid about our lack of work when my athlete said, “I’m really glad I can come to work out, and we can talk, and you’ll listen. I feel much better about everything.” I’ve been seeing that athlete ever since, and honestly, the quality of workouts has also improved.

I describe it like this: every session you coach, you typically have 2–3 expectations of what will happen, and your athlete also has a list of 2–3 expectations. Here’s a standard list of three for coaches:

- Your athletes will work hard.

- Your athletes will actively pursue their goals.

- Your athletes will have a great time doing so.

Those are definitely my top three as a coach for most of my sessions, and they probably cover a majority of the day-to-day coaching. But the thing is…your athlete’s list won’t always align with yours. This list could range from “I’m going to have a great time and hang out with my buddies,” to “This workout will get me out of the house and help me work toward my first fully healthy season,” to “I’ll become one step closer to earning a college scholarship.” Coaches run into issues when they automatically assume their athlete’s list does and should align 100% with theirs. And this is something I learned the hard way—it won’t.

You typically have 2–3 expectations of what will happen, and your athlete also has a list of 2–3 expectations. Your athlete’s list won’t always align with yours, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XGoing back to the story above, what would’ve happened if I only cared about the workout and projected my own expectations on him at that moment? Probably a lot of frustration for both of us, and who knows how long our time training together would’ve continued?

Now, let me address some concerns you might be having—this is not to say that you can’t hold athletes accountable or are not allowed to work hard. And this is not to say that your athletes will never have athletic goals that inspire you as a coach to do your best. But they won’t align 100% of the time. And sometimes, the solution is as simple as asking, which I have done before because it’s obviously not fair to expect the same list from a fifth-year bench warmer who just wants to be healthy compared to their teammate who’s a future draft pick.

Save yourself the headache and frustration: ask them what they want to get out of each training session and their goals, and ask yourself, “How do I give my athlete what they need today?” The great coaches understand that, almost always, the answer is more than just giving them a really good workout.

Lesson: Effective, long-term training relationships compromise between meeting your athlete where they are and creating a higher standard to help them achieve more than they thought they could.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9060]

There’s No Lesson Like Experience

Some of these lessons you may have nodded along with, and they made sense in theory, with the anecdotes helping drive the point across—but as much as I’d love to do the learning for you, you’ll need to experience these things yourself. Nothing would make me happier than if my crash and burn off Mount Stupid makes your fall a little easier. It’s a quick climb up and a quick fall down, but then a long trip ahead.

I’m very excited about all the smaller Mount Stupids I’ll climb along the way and the cool stories they’ll give me. Having an awareness of these lessons and how they can manifest in everyday training could make you better able to recognize them and adapt while on your own journey.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF