This is the story of how I don’t actually remember asking my mentor to be my mentor. Here’s the scene: it’s the end of August before I head off to start graduate school and I’ve coached at the same facility the prior two summers. The Director of Coaching and I always have great conversations, he asks insightful questions, and I genuinely enjoy our interactions. He’s helped me learn and grow beyond just the regular coaching hours, giving advice and direction for my time spent outside the facility. And just like every other young professional, I’ve heard about the importance of having a mentor…except, at this point, no one ever elaborated much beyond that. I never heard about how to find a mentor, how to be a good mentee, or examples of what mentorships look like in real life.

But hey, in theory, it all made sense to me.

Going into grad school with a full ride to be a graduate assistant was simultaneously exciting and nerve-wracking—I’m viewing this as my first actual job in the field. In order to maximize those two years, I know I need help to be the best GA I can be. I need someone who has already done the things that I want to do and someone to provide an unbiased opinion as I accumulate all these first-time experiences. A few days before my departure, about to move over 1,000 miles away from home, I decide I’m going to ask the Director of Coaching to be my mentor. Already having game-planned and rehearsed what I wanted to say, I walked up to him, nervous, heart racing, and reminded myself not to talk too fast.

“I’ve really enjoyed our conversations these last few years and as I go off to graduate school, I’d love for you to be my mentor.”

“Sure, that sounds great. What’d you have in mind?”

“I don’t really know. I just know having a mentor is important.”

This, of course, is pieced together from the bits and pieces I do remember and him retelling me that conversation an entire year later.

Deciding to ask for a mentorship was one of the best things I did as a young professional. At first, our mentorship was nothing more than being email pen-pals and connecting every two or three weeks, but I had someone who “gets it” that was in my corner. The one story I vividly remember from our emails was me almost deciding to leave grad school after barely being there for 30 days.

Deciding to ask for a mentorship was one of the best things I did as a young professional, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XThat first month, I spent an overwhelming majority of my time reading research papers on bar speed, power, and cluster sets of training (and, mainly, squatting). In and of itself, there’s nothing wrong with that. But coming from a coaching/applied background and knowing what I wanted to do (coach), as well as how this role was described to me initially…it just didn’t line up.

My thoughts were, “How do I tell them I’m leaving?”, “What do I even say to justify leaving?”, and “What am I supposed to do when I get back home?” I was miserable, didn’t know what to do, and there was no light at the end of the tunnel—a calm panic would be an accurate way to describe what I felt. I communicated this all over a few emails with my mentor, hoping for an answer (and, honestly, his approval to quit and come back). In response, a simple phrase came across my screen: “The grass is always greener on the other side.” A few other insightful comments followed, along with advice to “Stick it out a little longer, because you never know what could happen.”

Fast forward two weeks—everything changed. I started working with a few sports teams, I wasn’t stuck in a lab all day, and it started feeling like why I wanted to go there in the first place. And that was the beginning of an amazing experience in graduate school. Who knows if I would’ve stayed if I didn’t have the opportunity to express myself, feel heard and understood, and receive advice from an experienced professional?

I’m fortunate enough that this person has continued to tolerate my persistent question-asking to this day and that I can still receive mentorship. Not to give myself too much credit, but beyond simply wanting and seeking advice, I’ve done a bunch throughout our time together to make the mentorship more of a two-way street to maximize it for both of us. In this article, I’m going to share the two action steps that I always made sure to complete that have greatly accelerated and improved the mentorship experience. Additionally, I’ll be sharing the two biggest reasons why this strategy is incredibly valuable for both you and your mentor.

Steps & Strategies

Although this was never an explicit conversation—nor something written out as a deal to officially be a mentee—I settled on two simple but effective action steps. As the mentorship went on, the cycle I found us in was:

- I had topics and ideas I wanted to talk about.

- I took the advice that was given to me and acted on it.

Doing steps one and two then gave me ideas for the next topic to talk about. Rinse and repeat. It was this feed-forward momentum of conversation, action, conversation, action that built on itself week after week.

Then, as I continued to grow as a professional and the topics of our discussions shifted towards leadership and mentorship, I received feedback about how powerful it was that I took action on almost everything we talked about. I had no master plan at the time—simply put, we had a conversation and the solution made sense, so I acted. But looking back, there would’ve been no growth for me or the mentorship if it ended when the conversation ended.

I received feedback about how powerful it was that I took action on almost everything we talked about, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XStep One: Be prepared

Odds are, if your mentor is someone you find valuable enough to have as a part of your journey, they already have a lot going on and their free time isn’t always the most abundant. It’s your responsibility to make your time together as valuable, efficient, and effective as possible.

1. Know what you want to talk about. This is not to say that every minute of your meetings needs to be planned out, but even just having a few topics ready beforehand is going to give so much more structure and better results. Something is better than nothing, the more specific the better, but set both yourself and your mentor up for success by coming prepared. The last thing you should ever do is meet simply because it’s your “usual time to chat,” come in unprepared, and assume you’ll both be satisfied by the end.

- There are two types of topics: theoretical and real life. Theoretical topics are general ones like “off-season periodization” or “managing different athlete personality types.” Which to the general mentee, might seem specific enough. But that’s similar to someone asking me as a Speed and Performance Coach “How do I get faster?” Yeah, that’s a topic, but where the heck am I supposed to start? You can have general topics, but you need specific contexts.

- For example, if I wanted to become a college strength and conditioning coach, here’s how I would present a topic with a specific context: “Let’s talk about off-season periodization in the college setting, and how about for a fall sport like football and spring sport like baseball.” Then, to take this to the next level and be even more prepared, I’d look up the football and baseball team’s schedules from Northwestern University (my local Power 5 school, for example) and use those dates. That meeting is going to be immensely efficient and also effective by the end.

- The second type of topic is real life. If you are in a mentorship, I’m assuming you have a job/assistantship/internship that you’re working each day. This should give you plenty of opportunities on a weekly basis, if not a daily basis, to come up with examples to discuss. Be conscious of topics arising from your daily life and write them down before you forget.

- For example, I was recently on a consulting call about speed training with the performance staff at a university. It went well enough: not awful, but not amazing, and in the end I wasn’t satisfied with the closing of it all. I brought that to our next meeting along with the notes I had taken, and shared the story from beginning to end. The entire next hour was a whiteboard talk clarifying where it went wrong and brainstorming ways to handle that situation in the future. I had closure on the topic and tools to help me navigate my next call like that. The lesson being: “How do I close the deal when consulting for universities?” paired with “Here’s this detailed and specific example that just happened to me, can we go through it, please?” will set both you and your mentor up for incredibly more successful conversations.

- Lastly on this topic, it’s important to note the theme that it all comes back to real life and it aligns with where you want to go. Theoretical examples are rooted in real life contexts, and pursuing your goals gives you real life examples.

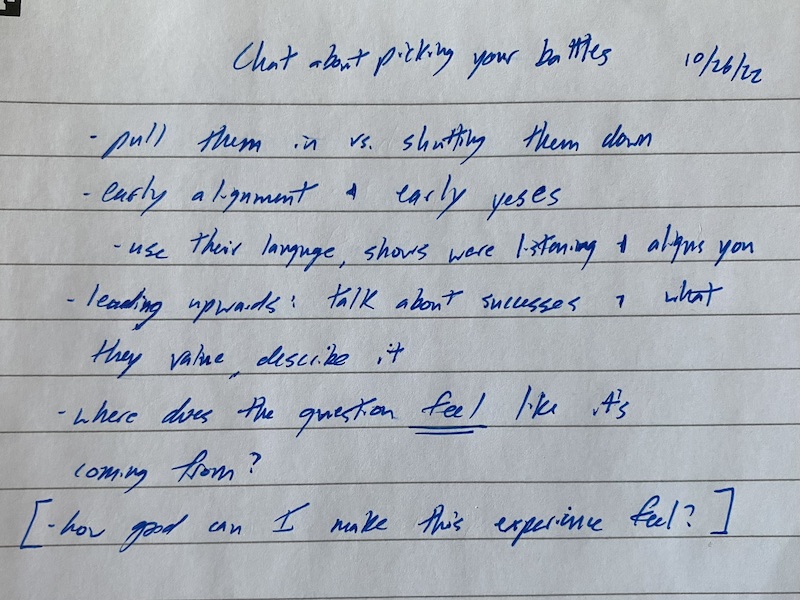

- Below is an example of notes I took after a conversation with my mentor. For the record, the legibility of my handwriting does not reflect my ability to write articles or coach athletes….

- Eight total bullet points took me five minutes, including some underlining and bracketing for what stuck out to me the most. If you’re actively listening (as you should be), you should be able to concisely summarize each chunk of conversation in a bullet point or two. It’s titled, dated, and concisely summarizes what we chatted about. My brain works by writing stuff down, but the more you do it you’ll learn what clicks for you.

Step Two: Act on the advice

This is the most important one. A good mentorship is a two-way street and this is your opportunity to hold up your half of the bargain. You are seeking advice because you want to improve—you receive the advice so you should act on it to bring it to life.

For example, I was chatting with my mentor about the value of the autonomy of coaching in the private sector and my facility at that time. As long as I know what direction I want to go as a professional and in my career, I can be as creative as I want to be with my athletes and fellow coaches to help me get there. Of my wanting to pursue sports science combined with speed development, he said, “As long as the athletes don’t get hurt, they do get faster, and they want to come back (which are all the basic tenants anyways) and whatever you want to do falls in the scope of our programming, go be a mad scientist. Every session you do can be an ‘experiment.’ Then document it and talk about it.”

My first “experiment” was “Are athletes faster when they race?” It was something we always said, but something I wanted to KNOW. Not to repeat the article I wrote detailing the process, but I slightly modified what we were already programming (which included racing), collected the numbers, and talked about what I found. In that moment it didn’t seem like much, but looking back, that’s what mentorship is and should be: an open conversation about wanting to achieve something more, a collaboration in brainstorming, and then action.

On the flip side, not acting on advice from a mentor is like not following a nutrition plan for weight loss that you paid for: you might feel good in the moment because you bought the plan, but at the end of the day and many weeks/months down the road, you’ll still be in the same spot you were when you started. Additionally, what kind of message is that sending to your mentor when you accumulate all this time together only to NOT act on the advice? Either that you don’t believe them or don’t actually want to improve. In either case, that mentorship probably won’t last long. When a conversation with your mentor is finished and you’ve both determined an action plan for the advice, do it.

When a conversation with your mentor is finished and you’ve both determined an action plan for the advice, do it, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XBeing prepared and taking action brings a pair of benefits:

Benefit #1: You are providing value back to your mentor.

As I mentioned, mentorship is a two-way street. People choose to help others because it makes them feel good, they’re “giving back” to young professionals, and it inspires them in return. But eventually, those feelings can fade. You can only take (their advice, their time, their knowledge) for so long until it becomes completely lopsided if they aren’t receiving any value in return.

Consequently, by acting on the advice of your mentors, you create stories for them as well. From mentoring you, they now have mini case studies where their advice is tested. They’ll learn what works, what doesn’t, and receive your feedback along the way. Then, when it’s the next time for you two to chat, you’re not only bringing engaging topics, but also anecdotes and feedback to elevate the conversation.

For example, my mentor and I were discussing how social media and building a personal brand are significant foundations for growing as a professional nowadays. My mentor always says that the positive results of consistently posting are unquantifiable. As you subtly become part of the social media algorithms and people see you consistently enough, they’ll reach out to you when something comes up. Then, from there, it snowballs and builds.

As you subtly become part of the social media algorithms and people see you consistently enough, they’ll reach out to you when something comes up, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XOur staff did a seven-day social media posting challenge. I was successful in my seven days and shortly after was asked by a follower to be on a podcast; then, shortly after that podcast was posted, a professional soccer team reached out about consulting. This is not only proof of concept, but also a powerful story that my mentor can now use for the power of his beliefs on social media.

Saying this isn’t intended to take away from the authenticity of a mentorship; not all motives and interactions are transactional, this all happens subconsciously. But the value the mentor receives in return changes over time: they go from feeling good for giving back to receiving actionable intel. Make your mentorship as much of a learning opportunity for them as it is for you.

Benefit #2: You start to create and accumulate your own stories.

How engaging would it be to listen to a podcast if the guest just recited their notes from Strength and Conditioning Theory 101 or Advanced Exercise Physiology? Probably not very engaging…but what if the guest shared their personal stories about applying that training theory to different age groups or how they applied that exercise physiology knowledge but had developed their own more practical version from doing it with a bunch of athletes? Probably much more engaging. The point is we all have the same information, but what makes someone interesting and intelligent is their lens and twist on that information based on their personal experiences.

I think one of the hardest parts about starting as a young professional, whether it be interviewing, trying to network with other professionals, or even mentoring coaches younger than yourself, is not having your own stories. You can really only speak on theory, what you’ve read in a textbook, and what the standard coaching answer would be. You don’t have enough experiences (aka stories) and anecdotes to share your own perspective. So, when it comes time to answer a tough interview question or share about your current situation when connecting with others, you need your own perspective, beliefs, and relatable stories to stand out and show that you actually know what you’re doing.

A former intern from my current facility is now a full-time strength and conditioning coach at the college level. He reached out wanting to discuss programming for top speed training. He came with specific examples of what he was doing and his first round of potential solutions. We discussed how many sprints per session depending on the time of year (pre-season, in-season, off-season), days of the week, and how to evaluate the data.

But the tone of the conversation flipped when I asked, “At how many flying 10-yard sprints do you start to hold your breath and get a little nervous that it’s too many reps?” He said, “I don’t know, 6 or 7. How about you?” This is when it switched from textbook talk to sharing my own experiences. We talked about my successes and findings from being creative with our top speed training, what I seem to always come back to despite all the variations, and what I’ve found from the data of my own athletes.

My advice resonated more with him because it wasn’t a one-and-done statement, it was advice followed by “and here’s why: (insert real life experience).” Although that anecdote might or might not be a direct result of me being mentored, it’s an awesome example of patience (something my mentor reiterates often, and I’m rolling my eyes just thinking about trying to be patient), knowing that I wouldn’t have been able to have that conversation and give that advice without all the stories I accumulated while coaching.

My advice resonated more with him because it wasn’t a one-and-done statement, it was advice followed by ‘and here’s why: (insert real life experience),’ says @CoachBigToe. Share on XTakeaways

Mentorship is a two-way street and just showing up to your meetings and saying you want to get better isn’t enough. That’s not going to maximize your time together, nor set you or your mentor up for as much success as you could. Instead, be prepared and take action. You must come prepared with questions and topics and take notes along the way. Then, your homework is to act on the advice and find out for yourself the truth of the advice in real life. Finally, come prepared to your next chat by bringing those results so they can learn too.

One of the stories my mentor references the most—and one of the stories I’m most proud of—goes like this:

On a random November evening, I’m outside doing yardwork and come back inside to find a voicemail on my phone. The message is from a very well-known coach in the field—in fact I own his book—and at first I almost don’t believe it. Once the shock fades, I pause and think to myself, “Wait, how the heck did they get my number?” Then I listen to the voicemail and hear that they’re calling about a job opening and want to gauge my interest.

But that’s not the crazy part…the crazy part is how they got my number. A technology company recommended me for the job…but not just any technology company. This company I had worked with on a variety of projects and whose products I had created content about for my own brand. This all combined as a demonstration that my knowledge, expertise, and professionalism were deemed worthy enough to recommend me to the coach. Not to go into the specifics, but this is a perfect example of connecting with and working hard for the right people, making good content geared towards where you want to go, and being patient (insert eye roll if you must). Those three things are some of the biggest themes of our mentorship together.

I know that my mentor uses me, the advice he has given me, and the stories I’ve created from our time together when it comes time for him to share his own experiences and anecdotes on leadership. And that’s how it should be. So not every session has to be ground-breaking and change the coaching world, but ask yourself every few meetings or after a big project, Would my mentor be excited to share this story with others? And if so, you’re on the right track.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF