A couple years ago, I wrote about the most unconventional thing we do in our track and field program here at Kalamazoo Central High School: the fly-by exchange in the 4×200 meter relay.

If you’ve ever seen this handoff in action, you know that it’s a bit…odd. The fly-by exchange inverts the traditional order of operations in which the outgoing runner takes off while the incoming runner chases him down to pass the stick, instead allowing the incoming runner to overtake his teammate. This places the onus to chase on the fresher, outgoing runner, who retrieves—rather than receives—the baton at full speed. It’s pretty slick—not only because it induces double-takes from those who haven’t seen it before, but also because it remedies several issues any 4×200 meter relay coach will be all too familiar with.

See, over the years, I’ve noticed that how a runner feels and looks at the end of a 200 can vary significantly from race to race. The most common symptom of this variability is that the outgoing runner, who is ready and raring to go, begins to run away from his tired teammate and then has to slow down in order to get the stick inside the zone. Other variations on this theme are that the outgoing runner, remembering having run away the last time, takes off turtle-slow from the jump; or that the incoming runner, being visited by the Ghost of Relays Past, has a vision of being left flailing, unable to catch his teammate, and panics, shouting “Slow! Slow,” destroying the relay time thusly.

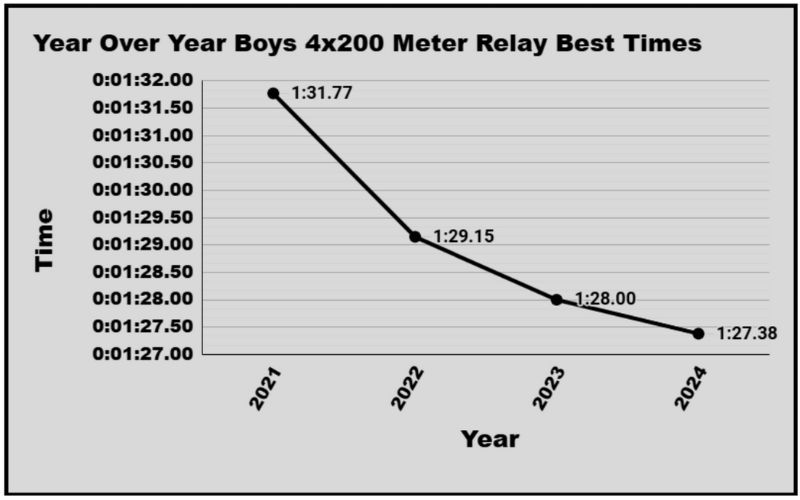

The fly-by exchange inverts the traditional order of operations in which the outgoing runner takes off while the incoming runner chases him down to pass the stick, instead allowing the incoming runner to overtake his teammate. Share on XWhen the incoming runner is allowed to overtake his teammate, he has only one job: keep running as hard as he possibly can. As a result, the outgoing runner has only one choice: sprint as fast as possible to catch him. The outcome is that both athletes are giving maximal effort at all times and the exchange doesn’t grind to a halt due to a missed connection. Anything we can do to minimize the deceleration of the baton through the zone will ultimately benefit the success of the relay. Since implementing this handoff with our boys’ team, our times have improved every year. This past season we broke a decade-old school record and finished fifth at the MHSAA State Finals.

For a more complete introduction to the fly-by exchange, feel free to check out my original article from 2022.

For the first three years of my tenure at Kalamazoo Central, we had an assistant coach overseeing the girls’ sprints, but due to staff turnover I started coaching our girls last season as well. In 2024, the first season implementing the fly-by exchange with our girls’ relay team, we ran almost a full second faster than the previous season, posting a best time of 1:46.99. We return several of our top sprinters to the team for 2025, and I anticipate an even better result this spring.

Before we go any further, now seems like a good time for some visuals, so you can see what this monstrosity looks like in action.

Video 1. The third and fourth leg of our 4×200 meter relay team practicing the fly-by exchange.

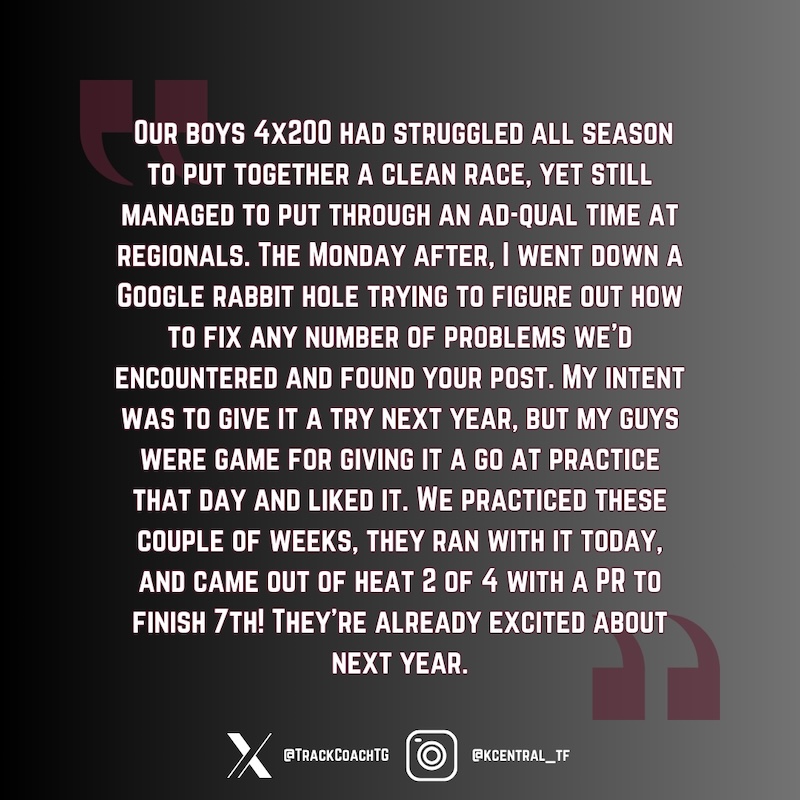

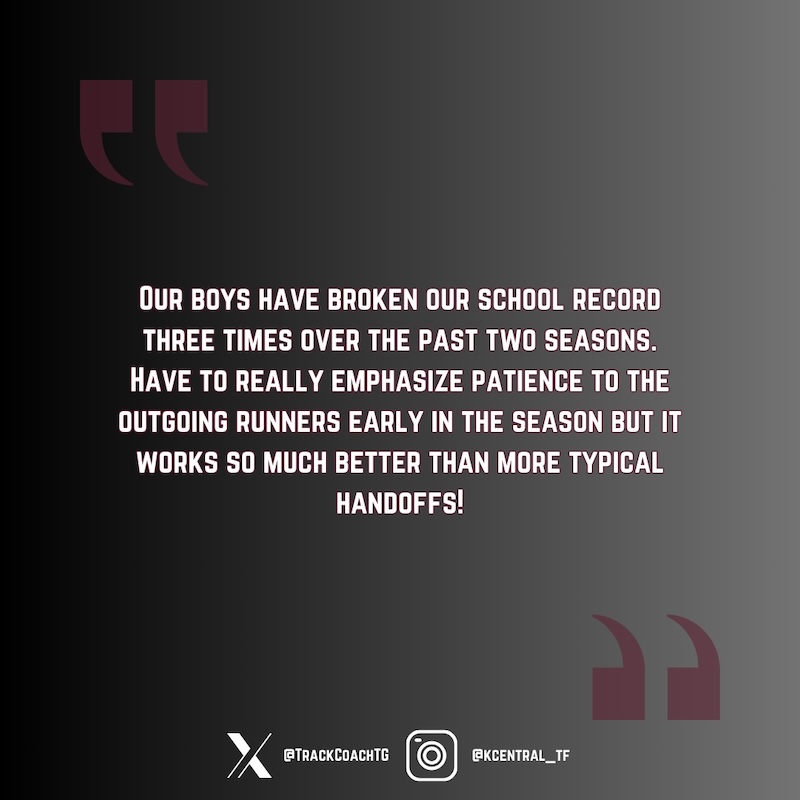

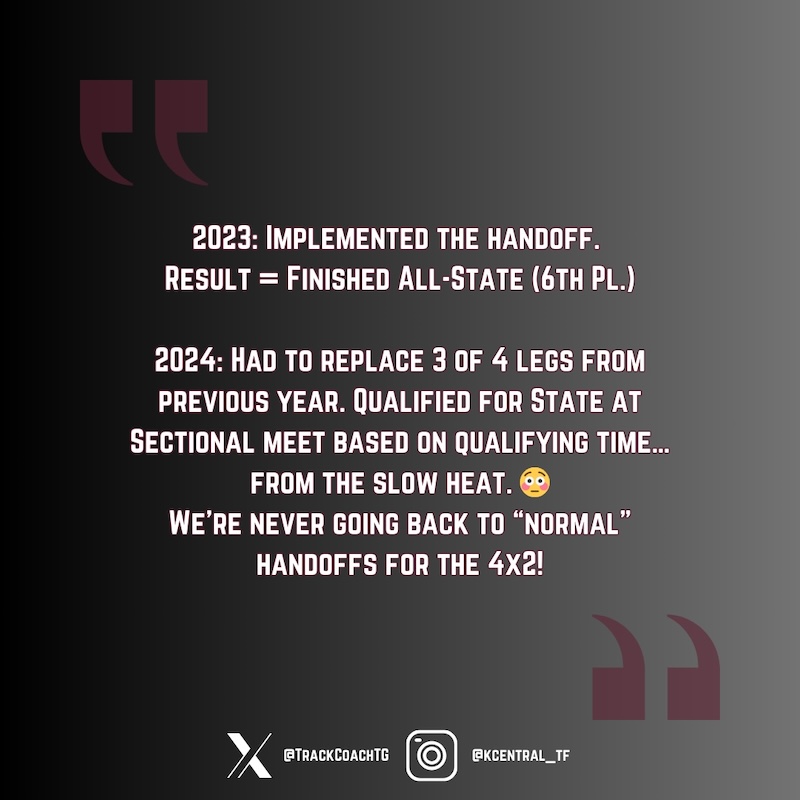

Since sharing my original article back in 2022, I’ve had countless conversations with other coaches about this method. Some are skeptical, most are curious, and more than a handful have begun to implement the fly-by exchange in their programs as well. Throughout the rest of this article, I’m going to sprinkle in some testimonials I’ve received from coaches who were brave enough to try the fly-by exchange, and kind enough to share their success with me. Across the board, those coaches who have adopted the handoff have been thrilled with the results.

Questions, of course, have come along with these success stories. And in addition to some of those questions others have asked, we’ve made some small modifications over the last couple of years to try to make this handoff as squeaky-clean as possible. The truth? Nothing is perfect. And as much as I would love to be able to tell you that this handoff is entirely foolproof, I just can’t do it. In fact, in 2023, we entered the state finals having run 1:28.00, which was the fastest time in Michigan up to that point in the season. On paper, we were favored to win…but as every coach knows, what it says on paper doesn’t always play out on the track.

We were sitting around third place heading into the final exchange, and we bobbled the handoff. Next thing I knew, the stick was rolling around on the track and the rest of the pack was headed into the homestretch while we could do nothing but watch the finish. We felt like we let one get away. It was a reminder that no matter what we do, the relays are volatile events and no matter what handoff method you employ, it always comes down to execution.

With that in mind, what comes next are some tips, cues, and considerations I hope will help to execute the fly-by handoff with as much consistency as possible and reduce the likelihood of heartache.

Video 2. Our 4×200 meter relay team at the 2024 MHSAA State Finals. We are in lane 4. Final time 1:27.38. As an additional viewing point, notice the team in lane 5 suffering the exact issue the fly-by exchange aims to address. Lane 8 also drops the stick due to an end-of-zone collision. No matter what we do, the relays are volatile events and no matter what handoff method you employ, it always comes down to execution, says @TrackCoachTG. Share on X

Coaching Cues for a Better Fly-By Exchange

In its simplest form, the fly-by exchange is fairly easy to coach: every athlete should be running as fast as they are able at all times. But, timing always matters for a good exchange—so, we really try to make sure the outgoing runner’s takeoff is on point.

One way we have done this is by creating a bigger visual target to use as a go-mark. In my original piece, I recommended starting with marks at five and seven feet before the start of the zone and adjusting from there, depending on your athletes. We have expanded the box on both ends, making marks at four and eight feet for most of our runners. In Michigan we are only allowed to mark with chalk , and this makes the box easier for our athletes to see.

In addition to expanding the box of our go-mark, we have placed additional emphasis on anticipating the moment at which the incoming runner hits the box, rather than reacting to it. Relays give us a unique opportunity to cheat acceleration by beginning with a knee bend into a forward lean, and then taking off with a rolling two-point start. This, plus the visual cue of an approaching teammate—rather than the auditory cue of a starter’s pistol—gives us an acceleratory advantage we want to maximize.

Therefore, I coach our outgoing athletes to prepare for takeoff while their teammate is around 20 meters away. This means they bend their knees and get into an athletic position. As the athlete gets closer to the go-mark, they start their forward lean, transferring weight to their front foot. They anticipate their teammate hitting the mark, just like a quarterback anticipates where his receiver will be by the time the ball arrives. If executed with perfection, when the incoming athlete’s foot hits the mark, the outgoing runner is already into his first stride. If this sounds familiar, it must mean that you’ve read this article about the Bang Step for the 4×100 meter relay. Our concept is very similar, and it’s easy to verify on video to show athletes whether they’ve left on time.

Another adjustment I’ve made is coaching how the incoming runner presents the stick to his teammate. For whatever reason, our guys were holding the stick at shoulder height. Probably my fault. If there’s any height discrepancy between the two runners, the outgoing runner sometimes looked like he was reaching up to grab the baton, which was pretty awkward. I now coach our athletes to hold the baton out in front at around belly-button height, so that no matter the size of the athletes, the stick is easier to grab.

A common question among coaches I’ve talked to is “are you sure there’s enough room for two athletes to be side-by-side in the lane?” In short, yes, I am. But, we still have to be intentional. One of the things we work on a lot is the concept of lane ownership. The incoming runner must stay to the inside half of the lane with the stick in his right hand. The outgoing runner must stay to the outside half of the lane, grab the stick with his left hand, and then transfer the stick to his right hand upon exiting the zone.

I’ve drawn a line with chalk to divide the lane in two in order to teach this concept, and it’s something we drill every time we practice the handoff. As you can see in the image below, both athletes are inside the lane even when side by side. We have never been disqualified for running out of the lane lines in four years of running this race with a fly-by exchange.

If you’re teaching this handoff for the first time and you need to convince your athletes there’s room for both of them, just have them stand next to each other inside of a lane. You will find, more often than not, that there’s enough space.

Of course, there are rare occasions where there may not be enough room for two very specific athletes. For example, what if you have a 6’3” linebacker handing off to a 5’9” running back and both of them are wide-shouldered athletes? We had this exact situation last year. The solution? We simply made sure that those two athletes were not on back-to-back legs. One of them ran first, the other ran third, and our two narrower athletes ran second and fourth. But in most situations with most athletes, with appropriate attention to lane ownership, it’s no problem. And with our female athletes, this is a complete non-issue.

Relay Order Considerations

The distance of legs of the 4×200 varies:

- The first leg will run up to 210 total meters, from starting block through the end of the first exchange.

- The second runner, who will run from the beginning of Zone One all the way to the end of Zone Two, will end up sprinting 230 meters.

- The same is true for your third runner.

- Your anchor leg will sprint 220 meters from the start of their exchange zone through the finish line.

My preference is to maximize my fastest athletes and those who may have a bit better speed endurance on the longer legs of the race, which means I’m not having those kids run first. So, who does run first? Remember all that stuff I said about outgoing runners anticipating their teammate’s arrival and leaving at the appropriate time? Whichever athlete is the worst at anticipating is probably your safest bet to lead off. Now, all he has to do is give the baton. But what if your fastest kid is also your worst anticipator? Look, there are a million variables. You are the expert on your own personnel.

For me, the things I’m most concerned with when it comes to relay order are the length of each leg, each athlete’s ability to anticipate their incoming teammate hitting the mark, each athlete’s 200 PR, their race-finishing abilities, and how much they hate to lose. Know your kids, experiment with your relay order, and decide what works best for you. We typically experiment until a week before our conference championship meet, then lock our relay order in for the rest of the season.

I can’t say for sure what this year’s relays will hold for us, but I will say this: if you see us at a meet, when the 4×200 relay comes around, keep your eye on Kalamazoo Central. We’ll be the ones doing the goofiest handoff you’ve ever seen, and if all goes according to plan, we’ll be celebrating in June. I hope you will, too, which is why I’m sharing the method behind my madness. Track is a beautiful sport: my team’s success does not depend on your team’s failure. When kids succeed, we all win. I’d encourage you to give this method a chance. After all, as numerous coaches have pointed out, it’s just crazy enough to work.