At bigger schools with large staffs, the strength coach with only two or three teams is available to attend staff meetings and work practices and competitions. And they can usually find time to meet regularly with coaches and athletic trainers without much trouble. But how can strength coaches at smaller schools with smaller staffs provide similar high performance value? When three of your teams are practicing at the same time that you’re lifting another group, it can be tough to stay on top of the daily goings-on for any given program.

Here at Lee University, my assistant and I work with about 300 kids. Between team lifts and open-hours sessions where we roll kids through seven half-racks (not to mention typical administrative work), unfortunately, we don’t have the ability to regularly attend as many practices or sports staff meetings as we’d like. To approximate a high-performance model in our context, we use technology to track some key performance indicators to create athlete data profiles that give actionable information to sports coaches, athletic trainers, and the strength staff.

This past fall, I used women’s volleyball as the guinea pig for our new Vitruve VBT units since it was the team whose practices I could attend the most. (The first few weeks were busy, as I was elevated to the head role just prior to school starting. I tried to average about one practice a week during the back half of the semester.) Being able to watch your team practice is such a benefit for the strength coach. You learn:

- What positions do they regularly find themselves moving into and out of?

- Can I learn some of the lingo to link our training with the language of their sport?

- What is the practice tempo—sure, reverse-engineering the work:rest ratios of competition is important, but they have to get through practice to make it to game day.

During breaks, I ask our coaches and athletic trainer how the girls have been looking, and it’s a good chance to quickly discuss how training has recently translated to the court. Luckily, with this team, our coaching staff is at every single lift. Some strength coaches may be wary of that, but I truly appreciate it—their presence shows that the weight room is important and keeps us connected as a staff since I can’t be at every practice. Regardless, a little face time at practice (and games, especially) goes a long way—you can pretend to care, but you can’t pretend to be there.

The kids and coaches eat it up when you can link your training exercises to a drill from practice or a sport-specific scenario, says wla_21. Share on XAs much as possible, maintaining a presence outside the weight room walls is also one of the easiest ways to get buy-in from administrators, coaches, and athletes. The kids and coaches eat it up when you can link your training exercises to a drill from practice or a sport-specific scenario. And the relationship factor obviously gets them to trust you quicker and more deeply. Often, the most effective staff meetings can occur in informal situations, like during practice breaks or passing by each other in the dining hall.

Technology Used

We use Google Sheets, TeamBuildr, the Just Jump mat, and the Vitruve VBT unit as our main pieces of technology.

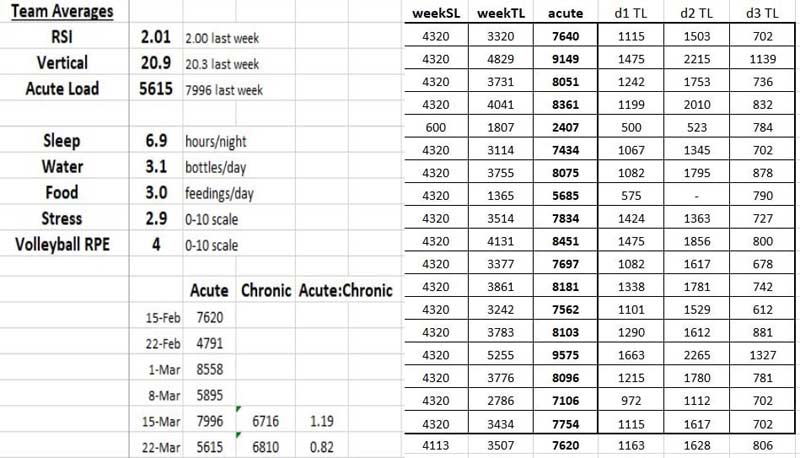

To begin each session, the girls enter their body weight into TeamBuildr, and early into the lift, we get a four-jump RSI score and a vertical jump as a readiness method, both of which they enter into Google Sheets on one of our two laptops. A short questionnaire in TeamBuildr on stress, sleep, and nutrition reminds athletes of their ownership in “the other 20 hours” and can paint a picture for S&C and athletic training as the stresses of the in-season phase pile up. Fortunately, the Vitruve app is synced with TeamBuildr to automatically record tonnage, velocity, and power for selected lifts.

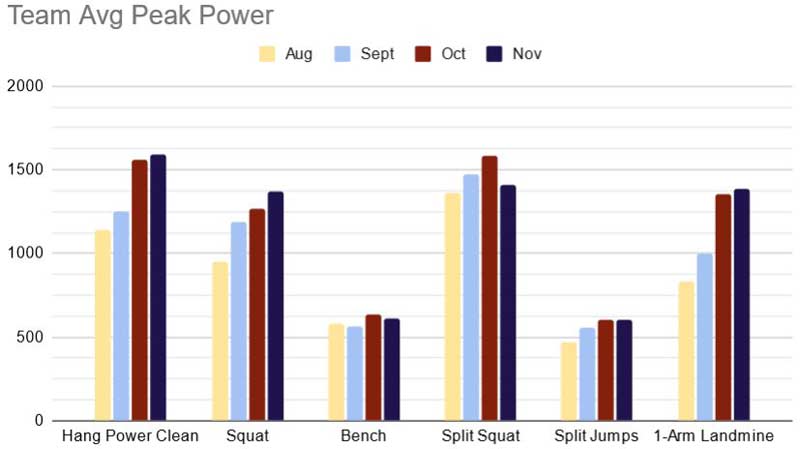

Peak power is the primary key performance metric we track for our weight work in-season—obviously, you have to move yourself with some suddenness to meet and contact the ball out on the court effectively. Grinding heavy weight for the sake of heavy weight doesn’t make much sense when factoring in mid-week games, travel, school stressors, etc. If a player’s power is slipping over the course of the semester, you need to manipulate your tonnage schemes, as power loss will show during competition.

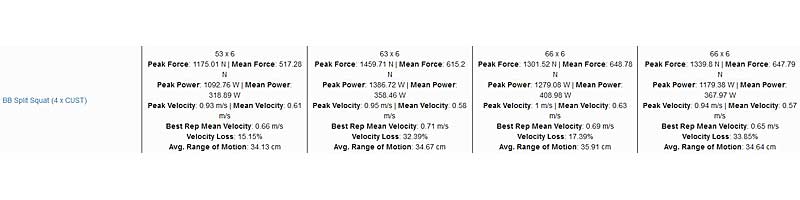

There’s a balance: last year, our single leg power dropped a bit despite our other lower body metrics improving. I may have gone a little light in our weight selection there, although we only had one session for that lift in November, so the data is limited compared to the other months.

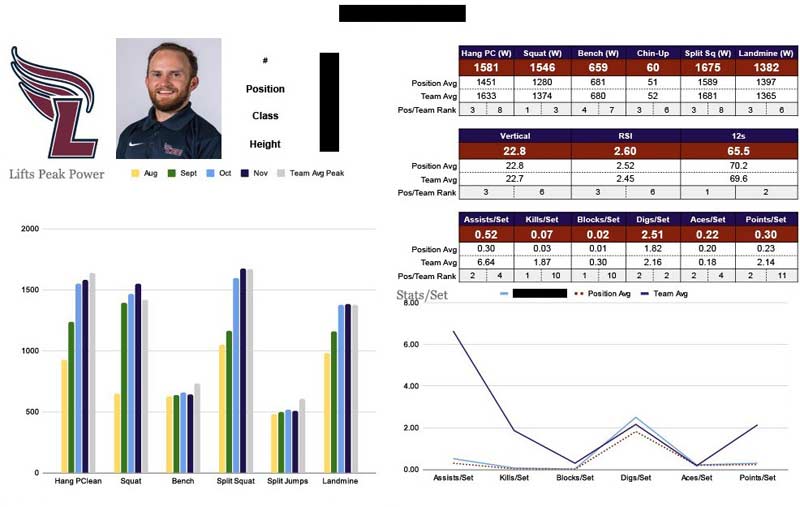

The athletes’ lift numbers are tracked each session, so we can compare them across time to their position group and team. Again, peak power is the figure I’m most interested in, and you can also prescribe lifts within velocity ranges if you’re so inclined.

In Google Sheets, the data validation function allows you to select an athlete from a drop-down menu, enabling us to rotate through each player’s profile quickly; all the numbers are copied from TeamBuildr into a separate “Roster” sheet that is referenced within the data profile sheet formulas. That “Roster” sheet also tracks changes over time for the assessments, while the data profile serves as a snapshot of a given testing week. In the future, we’ll be able to compare any given point of the season to the same point in time from previous years. Likewise, we can see the typical peak power for a particular position. With Vitruve and TeamBuildr’s combined tracking, I can get an idea of how set, rep, and tonnage variables affect power on both the micro and macro scales.

With Vitruve and TeamBuildr’s combined tracking, I can get an idea of how set, rep, and tonnage variables affect power on both the micro and macro scales, says wla_21. Share on X

By the end of the semester, I logged all their peak power numbers that Vitruve and TeamBuildr saved—I chose to track hang power cleans, squat, a split squat, bench press, a 1-arm landmine press, and split jumps. This range of exercises shows a total body, lower body, and upper body effort, as well as unilateral lower and upper body efforts. This weight room data is referenced in the master “Roster” sheet, which is then referenced to build their player profile. Color-coded charts show their (hopeful) growth as the semester progresses.

Varying your exercise selection allows you to improve the athletes’ KPIs with more specified lifts (e.g., moving from full to half to quarter squats, a strict landmine press to a push press to a jerk, etc.) without the training growing stale and progress stalling as you build a tolerance to exercises that don’t change. Did I try to cheat the system with my exercise selection choices to make our power trend upward as the season progressed? Absolutely—that is the entire point of periodization and hoping to achieve something of a peak in the team sport setting.

For example, the coaching staff felt that blocking was the skill that improved the most through the season; the vertical jump average increased 1.3 inches for our frontline rotation girls from August to November. The coaches and girls all felt that they were also striking the ball harder as the season progressed.

Integrating with Coaching Staff and Athletic Trainers

Comparing key sports statistics alongside the weight room numbers can provide good talking points with your coaching staff. Do a player’s stats match up with their athleticism? That question can start a conversation on the Four Coactive performance model (physical, tactical, technical, and psychological factors).

Might an explosive player be too slow reacting to visual patterns on the court? Are there any limiting factors keeping a girl with a high volleyball IQ from expressing it on the court?

Assessment lets us know exactly how each player compares to their teammates physically and in competition. If any area needs addressing, we know what we can work on. Particularly in team sports—where it can be tough to empirically quantify the effect size of drills/exercises/etc.—why guess in the few instances where you do have the ability to assess some factors?

Particularly in team sports—where it can be tough to empirically quantify the effect size of drills/exercises/etc.—why guess in the few instances where you do have the ability to assess some factors? Share on XAnd we can’t forget our athletic trainers! Since we track their athleticism numbers, ATs can have a baseline for return-to-play protocols. We might not have GPS/heart rate monitors or force plates lying around, but knowing an RSI jump or a 5-10-5 time gives us a reference for criterion-based reconditioning when making sure kids are ready to return to full-intensity drills. If a cluster of injuries pops up randomly, the acute:chronic ratio could be a good place to check.

In the past, we’ve done some questionnaires and monitored acute:chronic ratios by combining practice duration and RPE with tonnages in the weight room, but we’re gotten away from these more subjective measures in favor of tracking power throughout. Accounting for the systemic load of accessory movements can be challenging, and starting every session on the jump mat serves as a quick readiness test, anyway. It can be interesting to compare the kids’ practice RPE to a coach’s RPE, though—if the range is always wide, that can lead to some questions.

Obviously, a coach may think that a given practice should feel easy, but players could feel otherwise if it involves a lot of time on their feet or lots of landing at the wrong time of the year. Much like we periodize our workouts, coaches can mix factors like time, intensity, skill drills versus scrimmaging, etc., to keep practices productive and efficient.

At the start of every practice, the girls mark on a whiteboard how they’re feeling physically and mentally; this is an excellent way for our coaches to holistically see how both the team and individuals are doing daily. There’s a trust factor required on both ends. For the players—do I believe I won’t get punished if I say I don’t feel so great today? For me—can I trust what my team wrote on the board? If they say they’re fresh, then we can practice as scheduled.

Smaller schools, or those with smaller budgets, may have to get creative to implement a high-performance model, but it can be done. If our job is to support our coaches and athletes, we need to use everything at our disposal to make a positive impact, no matter our budget.

If our job is to support our coaches and athletes, we need to use everything at our disposal to make a positive impact, no matter our budget, says @wla_21. Share on XChoosing to train during the competitive period only makes sense if we’re increasing KPIs and giving the players a better capacity to express their sports skills. Tracking our power and trying to manipulate it upward through the season is a good way to feel confident that our training positively impacts performance. Technology can be a great supplement to the power of the conversations and the coach’s eye in a high-performance model.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF