Picture this. You’ve created the perfect program down to every rep. For the next few weeks, you know exactly what your athletes will do to succeed. There are even some colorful graphs that show the max recoverable volume for each week—something you’re extremely proud of. You gaze over the spreadsheet as if it were your firstborn child. Nothing can bring you down from the high of this moment—except for 32 kids dragging themselves into your weight room after a punishment conditioning session for penalties the week before.

Cue glass shattering sounds. One by one, your athletes fail this “perfect” program.

This is a real scenario I remember going through as a young coach in college. My program bit the dust, and we adjusted on the fly to squeeze out a worthless training session. I wish I could say this only happened once, but that would make me a liar.

I know that I’m not the only strength coach who has experienced this exact scenario. Maybe it wasn’t conditioning that got athletes; perhaps it was a lack of sleep, not eating enough, a heavy class load, extracurriculars, a crazy fad diet, their significant other dumped them, their dog died, etc. Whatever it is, you don’t always get 100% from your athletes—shoot, sometimes you barely get 50%.

This poses a very important question: In a setting with dozens of kids, how can we create a program to maximize each athlete’s session no matter the circumstance? There are many ways to do this, but a strategy that I have been using for years is autoregulation.

What Is Autoregulation?

Autoregulation is a training method that adjusts each session based on the ability of each individual that day or moment. This is affected by both their perceived capability and their actual ability. The problem with this strategy is that it is harder to periodize since each session’s “success” is left to the whim of the user.

Autoregulation is a training method that adjusts each session based on each individual’s ability that day or moment. This is affected by both their PERCEIVED capability and their ACTUAL ability. Share on XWithout control over volume or intensity, most coaches might feel like a captain without a sail. We all know that athletes vary in the way they want to push themselves. I was someone who would take it to an 11/10 each workout and just deal with the consequences: If my program sheet said I had a 365-pound clean, I was going to get it at all costs.

Conversely, I’ve worked with athletes who, when given the choice, elect to do NOTHING. We used to play a game with these types of athletes in college called SNIPER. A random coach would count all their reps and mark it down when they skipped any. Then at the end of the workout, BAM! we would punish them for every rep missed.

This is why it is important to know your audience and then build a program around them.

Autoregulate Your Weight Room

I’ve compiled a list of some of the different forms of autoregulation I use as well as the type of athlete I most use them on. I’ve also categorized these based on the simplest to implement to the most complex/expensive.

Ready Score (Age 14+, for ALL Sport Athletes)

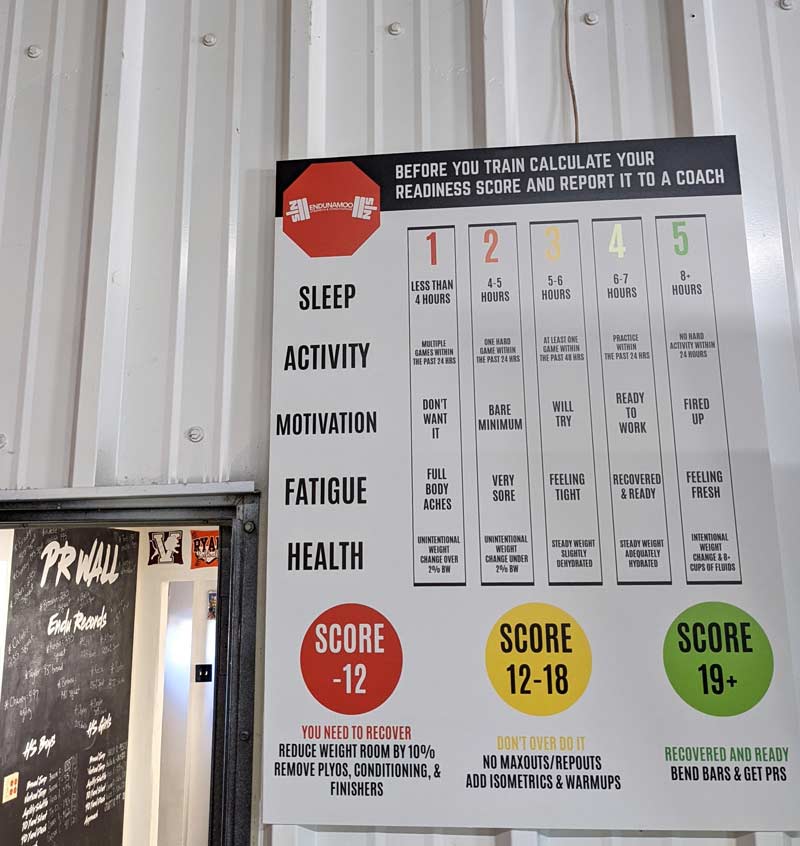

If I had a dollar each time an athlete told me that they were “tired,” I’d be competing with Bezos and Musk for richest person alive. For years, I would just say “me too” and laugh it off. It wasn’t until we created a simple score chart that we were able to quantify each person’s readiness and actually determine who was too tired versus who just wanted to complain.

There are many ways to do this, but our chart has three tangible and two intangible scores. This allows for true as well as interpersonal metrics to be considered. When a score is low enough, we adjust that individual’s workout to be less intense. We still get in a quality session, they feel like their feelings are heard, and we save a lot of frustration.

It wasn’t until we created a simple score chart that we were able to quantify each athlete’s readiness and actually determine who was too tired vs. who just wanted to complain, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XThe reason we say this is for kids 14 and up is that prepubescent athletes seem to have a hard time with introspective thought, and they recover much faster than their older peers. I’ve seen kids play six games over a weekend and be ready to go by Monday.

Max Reps (Age 12+, Basic Level of Weightlifting Knowledge)

This is one of the easiest ways to get in a lot of work in a short time. It’s also a great way to build competition into any program. The principles are simple:

- Perform a baseline set of reps (we do one to two sets of five, three, or one).

- Perform a max reps set following three rules: No repetitive bad form, no failure, and leave one rep for next time.

This can be as simple as allowing kids with younger training ages to get more volume or as complex as affecting each athlete’s progression based on the reps completed.

For example, in our program we have a “class leader,” which is the person who completes the most reps in one set during an exercise—it stimulates competition and gets more reps out of otherwise less-involved members. For progression, we use the rule if you can do more than the minimum but less than double, next week’s percentage increases 2.5%, and if you can do more than double you go up by 5%. So, for example, if we do a set of five at 70%, and they complete 12 reps on their max reps set, next week they will do 75%.

Rapid/Chaos Training (Age 16+, at Least 1 Year of Weight Room)

Whenever I talk with other coaches, I find this modality to be one of the least used in autoregulation. In the past few years, tempo eccentrics has become the golden calf of weight room training: it is worshipped. Strength coaches on Twitter drool over dozens of athletes squatting with synchronized uniformity. That being said, a growing amount of research supports the concept of rapid eccentric training in the weight room. (Here’s just one example.)

A rapid or chaos lift requires athletes to quickly lower and then ascend a movement to complete the set as fast as possible. Anyone can perform a rapid concentric, but it is astounding how few can perform a rapid eccentric with a little bit of weight. The autoregulation of this comes in the form of a stopwatch.

Anyone can perform a rapid concentric, but it is astounding how few can perform a rapid eccentric with a little bit of weight, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XSquats, for example, are a great way to challenge the rapid eccentric, since there is a turnover moment at the bottom. If I prescribe three sets of five at 50% 1RM, I will record their first set and challenge them to beat it. If they are able to move the weight even faster on the second set, I add 5% and challenge them again. The next week, we will start at a higher percentage and do it again.

Because emphasis is placed on speed over load, a tired athlete will simply move the load slower, while a prepared athlete will maximize speed gains. The greatest drawback of this autoregulation is that it requires a good coach’s eye. Athletes are notorious for compromising form for speed. Likewise, no increase in load should occur if there is obvious struggle or deceleration—a set of five rapid squats should not take 15 seconds.

Video 1. Rapid chaos lifting.

Velocity-Based Training (Age 16+, Requires Technology, 1- to 2-Year Minimum Experience)

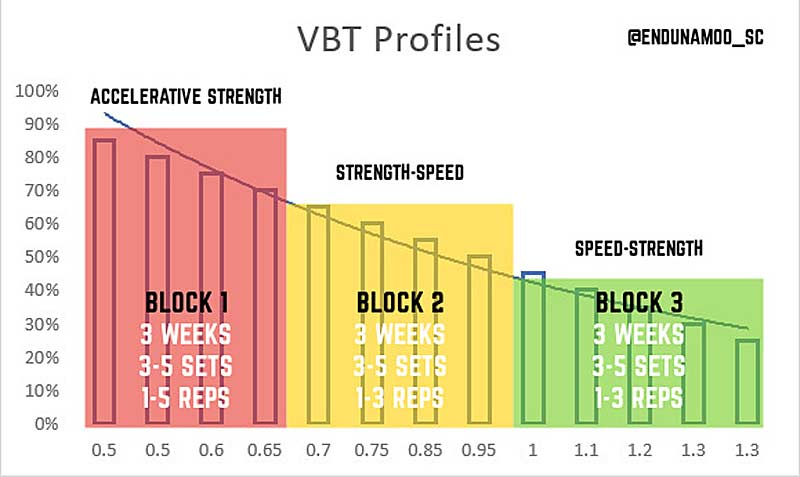

One of the fastest growing trends in the weight room has to be velocity-based training (VBT). It is by far the sexiest of the autoregulation methods I have brought before you today. To use this method, you must intertwine technology and the barbell to create the ultimate feedback system. I’ve even used VBT to conduct a study on fatiguability in weightlifters. There are many ways to autoregulate this, but first you have to determine what your goal is and then work to a weight and speed combination that achieves that goal.

To keep it simple, I will talk about the primary three zones of speed we work on and how to progress through them using a block strategy system. This is a force-to-velocity-based system, but there are many ways to do this:

- Block One: Weeks 1-3 (accelerative strength)

Starting at about 65%, your athlete will perform 1-5 reps for 3-5 sets. Our goal is to lift a weight between 0.5 and 0.75 meters per second (m/s). If they can move the weight faster than 0.75 m/s, you will instruct them to add 5% to the bar. The ceiling for most athletes will be 85% at 0.5 m/s for only one or two reps.

- Block Two: Weeks 4-6 (strength-speed)

Starting at about 45% of their 1RM, your athlete will perform 1-3 reps for 3-5 sets. Ideally, the weight will move 0.75-1.0 m/s. If the weight is moved faster than 1 m/s, they will add 5% to the bar; however, if it moves under 0.75, drop the weight by 5%. Starting in this block, speed will matter much more than weight as you prepare for the final block. At most, you can expect them to achieve 60% of their 1RM.

- Block Three: Week 7-9 (speed-strength)

Most athletes dislike this block due to the lack of weight, but a great VBT system can reinforce competition and effort by giving speed feedback. I like to make it a competition, having our guys compete for speed over absolute weight achieved. Start this block at 25% of their 1RM and perform sets of 1-3 for 3-5 total rounds. The weight needs to move between 1.0 m/s and 1.3 m/s and only increase by 5% each set that they achieve faster than 1.3 m/s. Your top performers will achieve around 45% of their 1RM.

Other than the cost of technology, this method does have drawbacks. For one, it greatly slows down the flow of your training. It can also be demotivating for certain populations of athlete to lift so little. I like to use this strategy during the season and with my older population (20+ year-olds) because it maximizes the day-to-day output of the nervous system without adding too much volume to already overworked athletes.

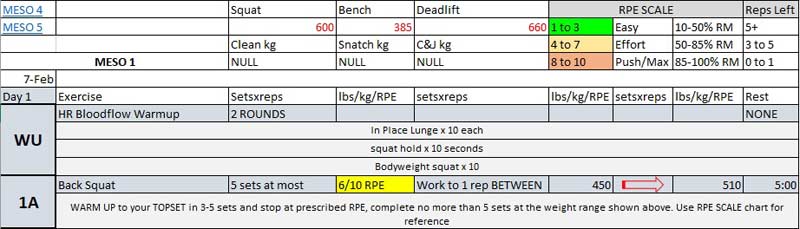

RIR/RPE (18+, More Motivated and Experienced Lifters, at Least 1 Year in Weight Room)

Reps in reserve (RIR) and rate of perceived exertion (RPE) are great ways to decide what weight can be lifted on any given day. I’ve used this with more success with barbell sport athletes than others, but it is still an option to explore.

The idea is that you provide a rep range and then prescribe an intensity based on feel. For example, let’s say that your athlete is working up to a heavy single at RPE 8 or RIR 2. Rather than leave them to their own devices, you will give them a percent range to work through.

For this, we will prescribe 80%-95%, allowing them to start with a very manageable percentage and then build up to a weight that achieves our RPE/RIR goal. The downside to this is that ego can really affect what an athlete thinks an 8 actually is. I’ve seen college kids grind out an obvious 10/10 only to turn around and cheerfully chime: “That was a 7.5. I’m going to add 5 pounds.”

No, you’re not, kid.

What to Choose

Some coaches may never fully embrace the nuance of autoregulation within their training; however, they don’t have a choice. When prescribing a percentage of weight, a sprint, or a plyometric for an athlete, their fatigue and readiness will affect the outcome of that exercise. When your athletes are tired and they fail their weights for the day, they’ve performed a max effort set and attempted an RPE 10 (even if it would have normally been an 8).

In contrast, you might find that you have a standout athlete who needs more weight to be at the appropriate velocity for your current block goals. Even when you have them sprint or jump, the variability within the day to day affects the output and, therefore, the desired adaptation of that session. This is why I am a big believer in manipulating the autoregulation that typically goes “unseen” by planning for it ahead of time. You may not have the resources or technology to capture every athlete’s daily performance, but you can build in self assessments that allow them to determine their max volume or intensity for that day.

When it comes to strength and conditioning, remember everything works a little, some things work a lot, but nothing works if athletes can’t even do it, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XBut now it is up to you to find out what you can autoregulate and whether your population can handle it. When it comes to strength and conditioning, remember everything works a little, some things work a lot, but nothing works if athletes can’t even do it.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF