In college sports, student athletes often see several strength and conditioning coaches cycled through every year. As a result, they can start to believe young strength coaches are only there in order to move up the ranks—particularly given the proximity in age. In order to achieve buy-in from the athletes, you have to convince them you care and are not just one more coach passing through.

When we look at any strong relationships in our life—our parents, friends, coworkers, classmates—what are the similarities? We give complete trust to those individuals, would probably sacrifice the only hour break we had in a 12-hour day just to make them feel at ease, would listen if they gave us career advice, and would trust they are looking out for our best interests. So why would that connection be any different between a coach and a student athlete?

Earn Their Trust

When I was 22 and entered the professional world of strength and conditioning, one thing I immediately noticed was that if you don’t have an age difference, bigger muscles, or a more successful athletic career, some athletes may think you don’t have anything to offer them besides time. For the most part, if you show them respect, they will show it right back. There may be a group of guys that will test your patience, but keep being consistent and showing you will not give up on making them better; if they are not for the program, then they will weed themselves out. Like the quote says, “Lower the bar and you lose the winners. Raise the bar and you’ll lose the losers.”

In order for an athlete to trust your program and buy into it, they have to respect your professionalism and know that what you are doing is going to benefit them. The best recipe for coaching is confidence—believe in your program, trust every second that you put into becoming a better coach, and project excitement to the athletes that these exercises are going to change how they play the game. They might go ahead and put some faith in your program and end up being a better athlete because of it. But don’t be fooled: they can spot a phony from a distance. Make sure you’re honest with who you are to them and be as open as you can be. If you are not a vocal, aggressive coach, don’t play that role, because once you lose that trust, it is hard to gain back. People respect honesty and transparency.

If you are not a vocal, aggressive coach, don’t play that role, because once you lose that trust, it is hard to gain back. People respect honesty and transparency, says @CoachKeemz. Share on XIf you want athletes to perform with intent and energy, they have to know you want them to succeed as much as they do themselves. One problem you may come across is student athletes who have had bad experiences with a performance coach in high school and now believe the negative stereotypes about strength coaches: that they are uneducated meatheads, they frequently injure athletes, and are just there to scream and cash a paycheck because they couldn’t succeed elsewhere.

So how do you resolve these types of trust issues with athletes? You show them how you are different from that coach who left a bad impression because you won’t give up on them, and you keep your positive energy consistent. The day you switch up who you are, the athletes will notice and look at you differently. There’s not a class or certification that teaches you how to be a “people person,” but it’s important to ask your athletes questions to learn who they are, what they want to do, what kind of family they come from, and so on.

A general “How are classes going?” or “How was your week?” can go a long way. Many student athletes are away from their family and friends and have no one to have real face-to-face conversations with, so it is nice for them to connect with the people they see the most: their strength coaches.

‘How are classes going?’ or ‘How was your week?’ can go a long way. Many student athletes are away from their family and friends and have no one to have real face-to-face conversations with, says @CoachKeemz. Share on XEarly on in my coaching career, I saw coaches I looked up to like Andreu Swasey in the weight room working out in the mornings before any athletes showed up—practicing what they preach and demonstrating the work ethic to wake up even earlier than the athletes in order to get their lift in. I also had coaches like Chad Smith, who would go through the workout routines and make his graduate assistants and interns join him in order to understand what the athletes would be feeling. This was powerful because coaches should always understand what the athletes are enduring and if adjustments need to be made. Thomas Carroll, one of my biggest influences, always preached, “Doesn’t matter how much work it is, do what’s best for the athletes.” He is a coach that treats his athletes like family and understands that it is not always going to be rainbows and butterflies, but will go out of his way to ensure both the athletes and the coaching staff are doing their best to succeed (and not just in their sport, but preparing for the real world, too).

Communicate with a Purpose

Another thing I’ve learned is that in the first couple weeks in a new institution, it’s good to try to reinforce the culture set by the sport coach and be a direct extension of them. I usually observe the overall response to their coaching tactics; knowing your athletes is an important aspect in coaching, because you want them to respond appropriately to your instruction. Vernacular is also crucial: talking the same language is important when you’re building a culture, and everyone has to be on the same page. If the head strength coach calls an exercise a “front elbow bridge” then do not go and call it a “plank.”

Talking the same language is important when you’re building a culture, and everyone has to be on the same page. If the head strength coach calls an exercise a *front elbow bridge* then do not go and call it a *plank,* says @CoachKeemz. Share on XReinforce the coaches’ main messages and be an extra voice saying the same things. Once the athletes know who you are and what your goals are in the program, they will respect your hustle and be comfortable accepting coaching demands from you. Many athletes have seen my own transformation in parallel with theirs: I came in to Florida International University weighing in at around 175 pounds, and just five months later was up to nearly 195; after dropping back to 185 pounds, at North Carolina Central University that’s risen up to about 215 pounds in the span of a year. The athletes at NCCU have also seen a corresponding change of strength as I’ve been able to add at least 50 pounds to my max in my back squat, deadlifts, bench, and clean by applying consistent work throughout the first seven months of my time there.

The best part is being able to show them the translation of strength into sport—my sprint times went down, my vertical went up, and my endurance dramatically increased. These changes showed the athletes that I was giving the same effort and consistency I demanded from them, and was seeing the kinds of results they wanted to see. There will be times where you will need to demonstrate exercises and shock some athletes. You may be put in situations where your athletic abilities need to be showcased, like a pickup game of basketball, a timed speed drill, or a competition with coaches—so be prepared for it all.

When demonstrating exercises, I have noticed during lifts if you mention how the exercises carry over to the field, athletes will perform them with greater intent. For example, if we are focusing on the triple extension of an Olympic lift, we might mention how this triple extension is always done when we jump, cut, or run and that might just be enough for them to push through as hard as they can. To scream at an athlete just because they fail to understand or execute might be a direct result of inadequate coaching, so instead of getting frustrated, try to explain the exercise in the way it would make sense to a young individual (because, after all, that’s what they are).

While coaching, bring that energy and show that you enjoy the job because energy is contagious. Nobody wants to be in a room moving any type of weight fast and have a silent coach stare at them with a poker face; even if it’s just a hop around the room with excitement or a “good job,” make sure you’re acknowledging the good consistent work you want to see.

Managing a Team

If you’ve been assigned your own sport team to coach, take advantage of it. Meet with the sport coach and have a needs analysis and annual plan to present, show them you know what you’re doing, and have something set in place to help while at the same time keeping an open mind to hear the needs of the coach. Once the training begins, keep the coaches updated with attendance, performance reviews, imbalances that you notice, special focuses you feel are needed to enhance an athlete’s performance, and anything you feel is important. You do not have to report every single thing to the sport coach, but keep in contact. If there is an assistant coach, contact them first because chances are the head sport coaches are much busier.

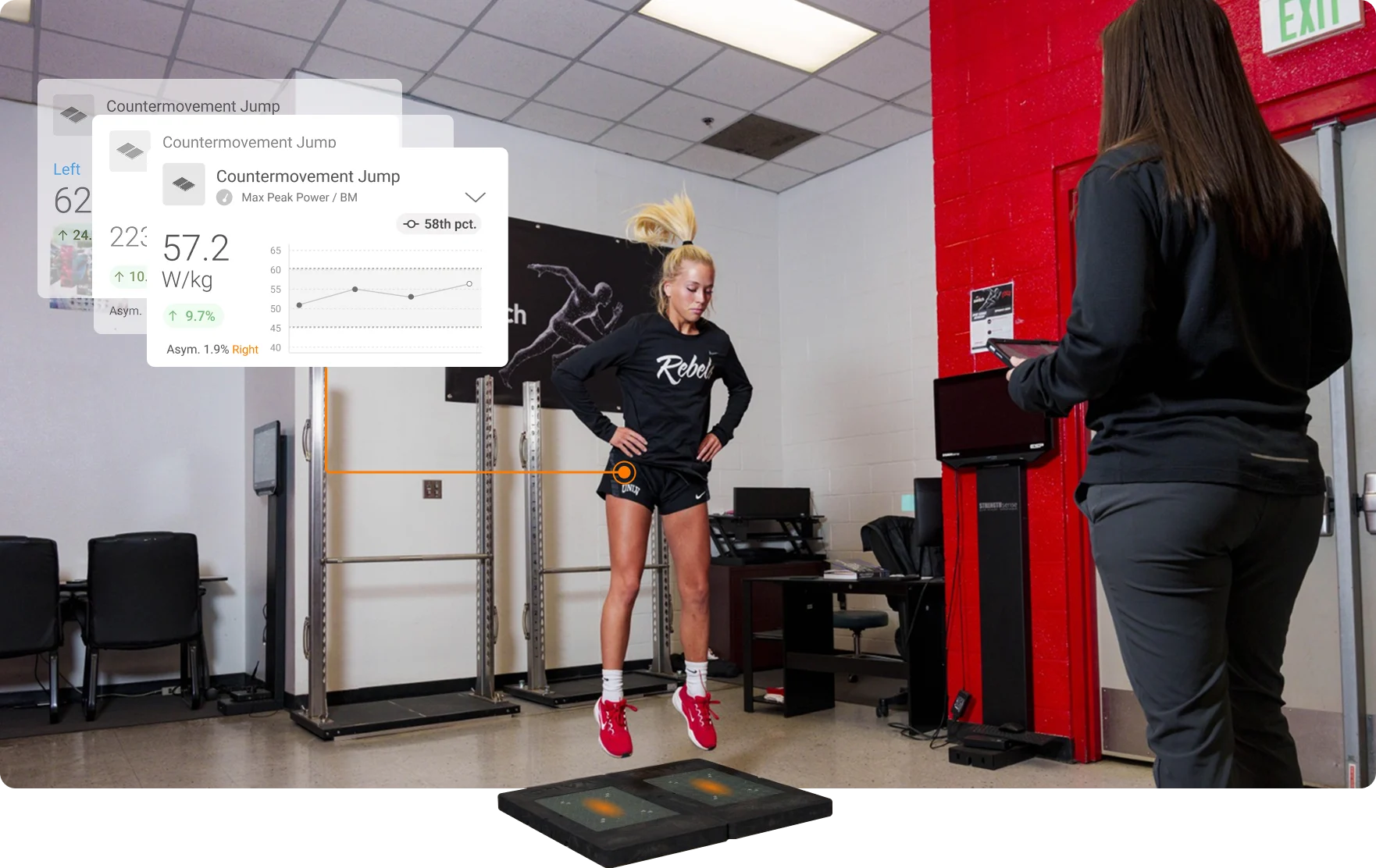

In order to get the performances you want from the athletes, it’s the little things that matter. Coach Jack Sprague and Mason Mathews told me to always meet the athletes halfway—to get what you want, give the athletes some of what they want. If a basketball player is squatting for force production, maybe plan some plyometrics to go with that because what basketball player doesn’t like to have more bounce? Just remember to implement it at the right time. Finishing the week with a good arm pump is something basketball players enjoy, especially since their jerseys don’t have sleeves. The confidence they get from feeling good in their uniform could transfer over to the court. Tracking progress data and/or pictures is another good way to show the coaches and athletes that improvements are being made and give them an extra boost of confidence in what you’re doing. These can also serve as a testimonial in case you have any future interviews as a strength coach.

Feel Free to Brag a Little

Athletes love a good story, especially if that story includes individuals they admire or activities they can relate to. Having something in common is a great way to build a relationship with trust. If you’ve had firsthand involvement in individual or team success, mention it. It can be as simple as relating something like, “I shadowed one of my favorite strength coaches as he trained Michael Thomas, and when they did these sprint drills Thomas saw an instant change to his sprint technique.” This field is one where you have to be a good salesman, so make sure you are able to use every resource in order to get your athletes to buy in.

Continued personal development is an effective way to bring something new to the table. One time during 6 AM lifts, I noticed a number of tired athletes, with many complaining about a lack of sleep and how tough the workouts were. I responded by describing two different studies that show the effect of hydration and sleep on exercise, and how if you lack either, exercise will feel harder than it might otherwise and also increase risk of injury.

Upon a couple changes recommended to these athletes, they acknowledged the fact that it might be on them to fix certain patterns—and soon enough, their energy levels increased and they began educating other players, creating a great culture amongst the team. It showed how being prepared and doing the little things in life can have such a big impact in the grand scheme. Even a minor tip from you as a strength coach matters, and could be what these individuals use to guide their lives and achieve greatness in their future pursuits.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF