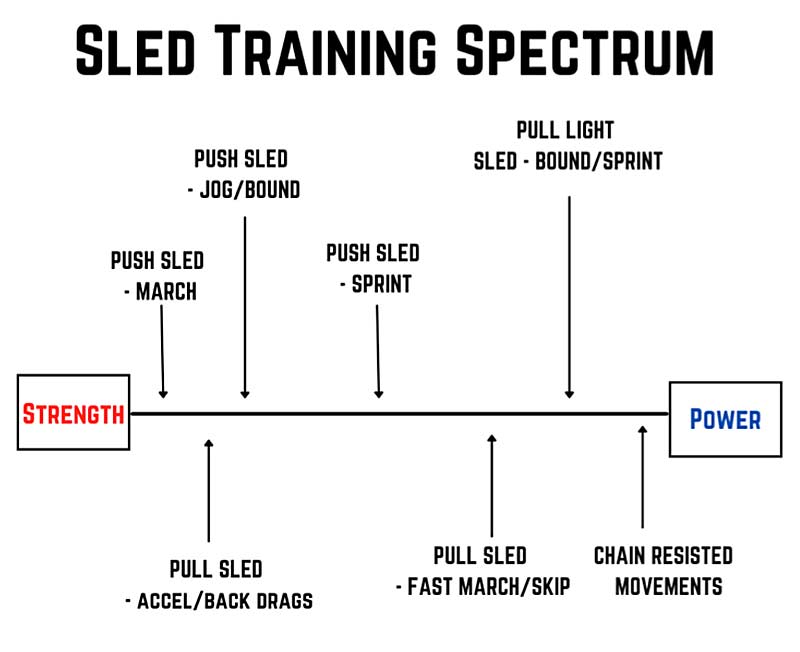

All training falls onto a spectrum. Categorizing exercise along a spectrum allows us to better program for specific adaptations and helps us organize our programs and ideas more efficiently—the individual and their needs determine where training will fall on the spectrum. We understand that the sled is a multifaceted tool for resistance training that can develop several attributes and serve as a solution to many problems, and sled training should have its own training spectrum to help lay out exercises in a structured manner.

Coaches should view the sled training spectrum as ranging between two categories of movements: those developing strength and those developing power. Share on XMany coaches still use the sled in a one-dimensional manner, prescribing the same training plan and load for all their athletes. This isn’t an effective way to structure training, as athletes have different needs and benefit from a more individualized training approach. Instead, coaches should view the sled training spectrum as ranging between two categories of movements:

- Those focused more on developing strength and strength qualities such as strength endurance.

- Those focused on developing power and power qualities such as power endurance.

Some other factors, such as biological age, training age, time of the year in regard to season, and individual weaknesses, will also be relevant.

Categorizing these exercises isn’t news to coaches—it’s common knowledge that the heavier a load is, the less speed the athlete will be able to achieve (and vice versa). Putting exercises onto the spectrum, though, is the next step past common knowledge, and this starts creating a system for accurate, actionable steps.

This article will begin laying out that spectrum of exercises for sled training, showing examples of how this can be utilized throughout training year-round and within a larger team setting.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9060]

Sled Training as Special Strength

First, I think it is important to note that I will be categorizing sled training here as special strength exercises: exercises that just so happen to be utilized throughout speed and movement sessions. Any time there are restrictions, such as load limiting maximum velocity from being reached, then that exercise is not a great option to directly train for maximum velocity. Although the power-based movements are closer to this objective, nothing will be as effective as flying sprints, or high-quality sprints without restrictions, to build that top-end speed.

In my experience, though, sleds have been effective for indirectly helping build that top-end speed by developing acceleration speed and enforcing better sprinting posture. They have also worked exceptionally well with youth athletes and field-based sport athletes.

The Strength Side of the Spectrum

Beginning to lay out the spectrum, we will start with the far side of strength. These movements have a greater reliance on force and are more general in nature. Exercises categorized by strength have longer ground contact times, are higher in load, and are performed at slower speeds.

Youth and less-experienced athletes tend to require more strength-based exercises—especially since many of these athletes aren’t yet fully mature and aren’t fully prepared for the adaptations that come with highly specific power-based movements. For them, using the sled is more of an unloaded, strength training exercise.

Some examples of these exercises include (but are not limited to):

Push Sled

The push sled starts the spectrum and can be broken down into a few separate series. Sleds can be categorized by:

- The body position they’re performed at (low, neutral, high).

- The position of the arms (either bent or straight).

- The speed at which they’re performed (marching, jog/bound, or sprinting).

Each position and speed has its own place on the spectrum and targets close, yet separate, performance abilities.

The lower the body position, the more strength-based it will be due to the increase in shin angle and longer ground contact times required to push due to the position. The arm position will also influence the exercise. Bent arm position movements lead to longer ground contact times and being more strength based. This is typically due to the increase in weight since the entire body can be used to drive into the sled. Straight arm position is typically associated with quicker ground contact times and puts more stress across the trunk and spine to stabilize, as the load is farther away from the body.

You can use a variety of sleds—it isn’t necessarily about the sled you have, but rather how the athletes position themselves with the sled. Share on XThe videos demonstrate a variety of sleds being used to show that it isn’t necessarily about the sled you have, but rather how the athletes position themselves with the sled.

1. Push Sled Low – Straight Arm Position

2. Push Sled Neutral – Bent Arm Position

3. Push Sled Neutral – Straight Arm Position

4. Push Sled High – Bent Arm Position

5. Push Sled High – Straight Arm Position

Most of these movements will fall in the middle ground of 10-20 yards, but it all depends on how the athlete performs them and the goal in mind.

Pull Sled

Pulling the sled is usually associated with more of the power-based exercises, but the acceleration drags and basic forward walks are used to develop strength and the ability to produce high amounts of force into the ground.

Each variation will require a strong, neutral body position to optimally pull the sled down the field, can be loaded extremely heavy, and will be painfully slow in comparison to actual sprinting.

Forward

1. Acceleration Drag

2. Forward Walk – Waist

Dragging the sled backward is great for durability of the knees and can be used to strengthen the knee extensors, as you have to drag it by stepping toe-to-heel and deliberately extending at the knee. Like the push sled, there are various positions and speeds that you can use with dragging the sled backward.

Dragging the sled backward is great for durability of the knees and can be used to strengthen the knee extensors. Share on XEach position will affect the efficiency of the movement, but also the other muscle groups that are involved. The pull and underhook variations will require more upper body strength and stability than dragging it with a belt around the waist. And while all the variations can be done at various speeds, having the belt around the waist will allow the arms to be involved in the exercise and make it more accessible to increase the speed of the movement.

Backward

1. Back Drag – Pull

2. Back Drag – Waist (Slow)

3. Back Drag – Waist (Fast)

4. Back Drag – Underhook

These exercises can be performed for longer distances if trying to build up strength endurance or loaded heavy to pull for short yardage to increase strength. Use them at your discretion but keep your goal in mind.

The Power Side of the Spectrum

Power-based movements are defined by:

- Being velocity driven.

- Having shorter ground contact times.

- Being performed with less load.

- Being performed at higher speeds.

These movements are more specific, and elite athletes have the most to gain from them. Some examples of these exercises include:

Pull Sled

If you have athletes pulling the sled to develop power, they have to do it with lighter weight and in a more rapid, aggressive manner. Each movement is focusing on quick hip flexion and short contact times of the foot reflexing back off the ground.

Many of the speed exercises your athletes perform, such as skips and bounds, can also be performed towing a sled; they just have to be done in an appropriate manner focusing on quality of movement.

1. Marching

2. Skips

3. Bounds

4. Sprint—moderate to light weight

Perform for sets of 10-20 yards with light to moderate load.

Piston Sprint

The piston sprint is a pull sled variation that emphasizes aggressive ground contact frequency. For each variation, you want to maintain strong body posture. Pulling will naturally be more upright compared to the push and focus on repetitions into the ground with a full range of motion.

Perform for sets of 5-15 yards with light to moderate load.

1. Push

2. Pull

Chains

I know putting chains on this list is technically cheating, but chains are a great alternative to sleds for sprints where you want to gain more of an upright body position with less drag. Since chains are lighter and have a length to them, the resistance is more spread out as opposed to a single dense weight you have to pull.

Perform for 10-30 yards with one to three chains.

1. Sprints

2. Bounds

The spectrum is not limited to the exercises shown above, and you can easily add several other movements. Even the exercises shown on this spectrum could be used for the opposite adaptation if performed properly—it is how the exercise is performed that drives adaptation, not exercise selection. However, I selected and placed some exercises on the spectrum because they better fit the need to develop those specific adaptations due to the body position, arm position, or load used.

How to Apply the Spectrum in Your Training

When implementing the spectrum in your programming, it is best to go on a case-by-case basis. Some athletes already have an acceptable level of strength and can begin with more power-based exercises. These exercises are not inherently better or more difficult than another—they are just focused on different adaptations. That also doesn’t mean that those individuals should neglect the opposite side of the spectrum; instead, they should spend most of their efforts on the exercises where their weaknesses are and try to do the minimum to maintain their strengths.

Instead of neglecting the other side of the spectrum; athletes should spend most of their efforts on the exercises where their weaknesses are and do the minimum to maintain their strengths. Share on XYou will rarely find an athlete who is completely on one side or the other. It is usually a mixture of various strengths and weaknesses.

Programming Examples

General eight-week program for a field-based sport athlete.

Ratios: (Strength: Power)

The ratios refer to the percentage of volume of exercises being performed on that side of the spectrum, not weight-based percentages. So, an athlete who is eight weeks away from season will spend 90% of their time working to develop strength-based qualities by performing movements such as heavy sled pushes from various positions and acceleration sled drags. Meanwhile, they will only spend 10% of their time working to develop power-based qualities with exercises such as lighter sled skips and bounds.

Never leave any quality out, although as they get closer and closer to the season, that spectrum will see a shift in the volume of work being performed in each category (becoming more specific in nature as the season approaches). Many strength training programs follow similar principles and will consolidate nicely.

Week 1 – 90%: 10%

Week 2 – 90%: 10%

Week 3 – 75%: 25%

Week 4 – 50%: 50%

Week 5 – 50%: 50%

Week 6 – 25%: 75%

Week 7 – 10%: 90%

Week 8 – 10%: 90%

This is a basic example and won’t fit all athletes, but it gives you a general idea of how you can lay out training. More elite athletes would spend less time with the strength side of the spectrum and younger, less experienced athletes would spend more time there.

Also, if you find an athlete who is already strength-sufficient but lacking in the power and speed department, then that athlete can start farther down the spectrum, closer to the power qualities.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11130]

Programming Applications for the Private Sector vs. Collegiate

Implementing this spectrum in the private sector has worked extremely well, as I am not limited by time of the session or what I can do with my athletes. Even in my largest group of 12 athletes, I can still take my time to equip each with what will fit them best at that moment. However, the private sector does lack the frequency of training, as many athletes are not on a consistent schedule. This is why I never recommend leaving any training quality out—while not as efficient as putting all of our eggs in one basket, I need to spread my eggs out and make sure athletes are prepared at all times. Many athletes play sports year-round and unfortunately won’t get a two- to three-month off-season to develop physically.

In the larger collegiate setting, on the other hand, each team can begin with more strength-based exercises to develop the strength needed to enhance the power exercises later down the road. In that environment, I know I’m going to have my athletes for at least a few weeks of consistent training before games, school, and personal lives get in the way.

Even with that said, creating a semi-individualized training approach could serve your athletes better. Start by profiling your team and putting athletes into two groups: one strength-focused and one power-focused. Place each group on the spectrum where you want them. I would recommend just having two groups—trust me, you do not want to spread yourself too thin. When selecting exercises, either use different movements from the spectrum or the same exercises but forced to fit within the demands of the adaptation, so the groups are performing the same exercise at different speeds, weight ranges, and ground contact time periods.

When selecting exercises, either use different movements from the spectrum or the same exercises but forced to fit within the demands of the adaptation. Share on XIn each cycle of training, an athlete could change groups. This will be based on your testing and profiling of your athletes (as discussed further in the next section). That way, you are constantly attacking the athlete’s weaknesses and never fully neglecting an adaptation.

I understand that this is not an exact science, but it will serve your athletes far better than having them follow the same program and load prescription regardless of needs or experience.

Profiling on a Continuum

I’m sure you’re wondering how to actually profile your athletes by strength or power needs. Common knowledge and the coach’s eye go a long way, but I’ve found success using Cal Dietz’s free calculator. This tool examines an athlete’s 10- and 20-yard splits to profile them within a specific training range.

Once given that range, it is easier to place them along the spectrum based off their need to develop one of the training qualities. The goal for using this spectrum and sled training in the first place is to enhance their speed, so having a 10- and 20-yard time is a good start. Defining their needs first puts you in a better position to have a why in prescribing exercise selection, load, and goals.

Training is complicated enough. There are so many branches of physical preparation that intertwine with each other, with other training models, and even with other professions. The layout of the spectrum will help save you time and more accurately prepare for your individual athlete’s needs, both of which can help make training a little less complex.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF