Dr. John Harry is an applied biomechanist who studies human movement. He has specific expertise in the assessment of lower extremity movement execution and control during ambulatory tasks in both healthy and neurologically impaired populations. His research agenda centers on 1) the identification of unique physical presentations during locomotion in children and adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and 2) physical performance assessments in athlete and tactical populations.

Freelap USA: The rate of force development (RFD) is a small part of performance during sport. Can you explain why coaches should care about this single metric and clarify its value in jumping?

John Harry: It is true that RFD, or more formally “yank”1, is only a small part of sport performance. With that said, I do feel that yank is an important metric for jumping because both jumps and on-pitch/court sporting movements involve a reversible action executed as quickly as possible to maximize performance in time-constrained sports environments2.

I view yank as a “strategy” metric in vertical jump analyses because it is not a direct “driver” of performance. Instead, it is a reflection of a jumper’s volitional organization. This is because yank is most often calculated as the rate of change of force during a specific movement period. So, any change in yank is directly influenced by the change of force and/or the change in the time of force application.

Yank therefore provides information for how an athlete or group of athletes strategize force application3,4 in addition to how they change (or retain) their force application strategy in response to an acute environmental5 or chronic training6,7intervention. In my view, yank is a “look here first” metric when seeking to explain changes or a lack of changes in jumping ability from a force application perspective. If jumping performance changes alongside a change in yank, we would know the jumper’s force application strategy changed, and the respective force and time data should then be explored independently to really understand how the strategy changed.

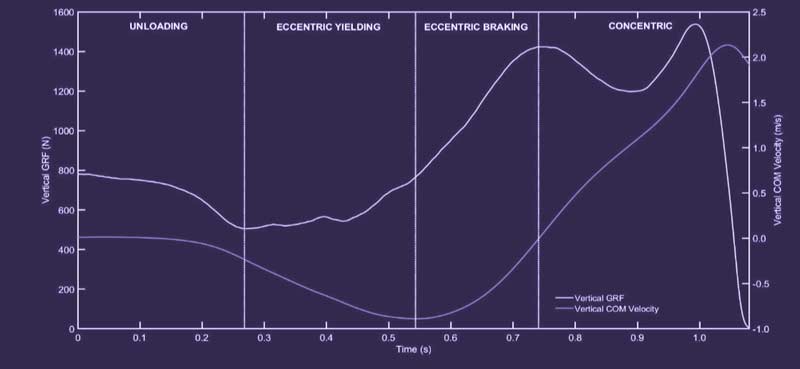

Because the high effort reversible action during vertical jumping is mechanically and functionally similar to the reversible actions that occur during on-pitch/court movements, yank is best used when the force-time curve of a jump is deconstructed into phases that are mechanically and functionally linked to the phases or key periods of time within other dynamic movements or training exercises8. The phase deconstruction method I recommend for countermovement jumping incorporates the following phases, as shown in Figure 1:

- Unloading – time when force is reduced to a minimum before force application occurs.

- Eccentric Yielding – time when force is actively applied via predominantly eccentric actions, but the downward center of mass is increasing, and the athlete is yielding to gravity.

- Eccentric Braking – time when force is actively applied via predominantly eccentric actions and diminishing the effect of gravity to decrease downward velocity.

- Concentric Propulsion – time when force is actively applied (mostly) via predominantly concentric action, and gravity has been overcome and the center of mass moves upward.

Others have used similar terms for different periods within the jump, such as unweighting9,10, or different terms to describe the same phases, such as defining eccentric braking as the “stretching” phase11. Because of this, readers should be aware of inconsistent terminologies when reviewing results or planning their own analyses. Nonetheless, use of appropriate jump phases, regardless of nomenclature, can maximize the usability of yank results as it relates to physical ability, neuromuscular function, and/or responses to training or lack of training.

Recently published and (hopefully) soon-to-be-published studies from my lab and from my colleagues’ labs and team testing environments support the use of yank as a key jump strategy metric. Our results indicate eccentric braking yank may be the “most important” strategy metric associated with changes in vertical jump performance.

For instance, when testing a group of athletes, we typically define jumping performance by the “explosiveness” of the jump, estimated by the modified reactive strength index (i.e., ratio of jump height and jump time). We’ve found that, in high-level collegiate male basketball players, eccentric braking yank is the strongest force-specific strategy predictor of explosiveness during vertical jumping.12 Moreover, when stratifying those athletes into sub-groups with higher and lower explosive jump abilities, the high explosiveness group displayed much greater eccentric braking yank than the low explosiveness group.12

When changing the population to trained females, we’ve also observed that eccentric braking yank is significantly correlated to explosive vertical jumping performance but not to absolute vertical jump height.13 For context, eccentric braking yank reflects the effect of a jumper’s volition to stop their downward velocity. If we use a simple car analogy, the jumper’s volition during eccentric braking is akin to how connected the brake pads are to the brake discs, with a stronger connection meaning a more forceful decrease of velocity. So, eccentric braking yank reflects neuromuscular function during the time when mechanical energy is stored for potential reutilization when transitioning between downward and upward movement.14

Eccentric braking yank is not the only important yank metric to explore during jump tests. For example, we recently explored changes in vertical jump performances of professional male footballers (i.e., soccer) after 15 weeks of quarantined training during the recent shutdown for the COVID-19 pandemic. Our preliminary results revealed that eccentric yielding yank was significantly reduced following quarantined training even though eccentric braking yank and jump performance (height and explosiveness) were unchanged.15 To us, this means when the athletes returned to directly supervised activities, they were not ready to adequately meet the demands of the rapid reversible actions characterizing elite football, and focused training should take place to restore or refine their eccentric strategies before returning to competition.

We can use the simple car analogy again to contextualize eccentric yielding yank. A jumper’s eccentric yielding yank represents their volition when pressing the brake pedal. As pressing the brake pedal occurs before there is an actual decrease of velocity, eccentric yielding yank reflects the strategy employed to initiate the braking process while downward velocity continues to increase. Going back to our results, had we overlooked phase-specific yank as a strategy metric, the results would have indicated the athletes were likely ready for competition when in fact they were not.

If we quickly switch from vertical jumping to horizontal jumping (i.e., broad jumps) in collegiate male footballers, we’ve recently observed that the strongest strategy predictors of explosive broad jumps include unloading yank along the vertical and anterior-posterior axes16. Interestingly, eccentric yielding and braking yanks were not predictive strategies of explosive broad jump performance. This tells us two things. First, explosive vertical and horizontal jump performances rely on unique phase-specific yank strategies. Second, a jumper’s ability to concurrently reduce their standing vertical force application and rapidly apply horizontal force into the ground may need to be targeted to strategy outcomes to improve horizontal jumping explosiveness following a training intervention.

It may be appealing to rely on phase-specific yank as a direct reflection of jump ability, but I encourage coaches and practitioners to only use yank as a direct reflection of jump strategy. Share on XTo tie things together, it is my opinion that all jump tests should include phase-specific yank metrics to understand two main points. The first it to discern the force application strategies employed by athletes to jump explosively. The second is to identify the strategy changes that reflect athletes’ neuromuscular readiness to handle the demands of sport. It may be appealing to rely on phase-specific yank as a direct reflection of jump ability, but I encourage coaches and practitioners to only use yank as a direct reflection of jump strategy.

Freelap USA: Minimalist shoes have been promoted as a way to help athletes improve performance, but so far, the research is mixed or scant on what they really do. Can you explain some of your findings on the topic?

John Harry: I think people view shoes as a low-hanging fruit in that changing shoe types will help an athlete improve. Much of the running literature suggests that a change to minimalist shoes will affect certain performance qualities depending on how the shoes are implemented. For jumping, minimalist shoes can, in theory, have a similar impact on performance. However, mixed results have been presented on whether minimalist shoes actually stimulate jump performance changes. I’ve got my beliefs on why results are mixed, and I’ll use some evidence from my lab and others’ labs to try and unravel the seemingly mysterious minimalist shoe effects during jumping so that current and prospective users can get a grasp of the current evidence.

My first exploration into minimalist shoe effects on jumping performance and associated neuro-mechanical outputs17was meant to be a replication/expansion (which I wish I’d see more of in the literature) of the study by LaPorta et al.18, who observed that minimalist shoes enhance jump height and peak power production in males and females. However, we did not observe any change in vertical or horizontal jump performance (height and distance) when wearing minimalist shoes (nor when barefoot) versus standard athletic shoes. We did see some changes in muscle activation, so there is likely a minimalist shoe-related change in jump strategy, but the change of strategy is not large enough to change mechanical output or jump performance.

We initially thought the discrepancy between our results and LaPorta’s results was partially explained by our use of only male participants versus their use of a pooled sample of males and females, different types of minimalist and standard shoes, and unrestricted versus restricted (i.e., no arm swing) jump techniques. Our 2015 study17 also focused on force platform variables alongside muscle activity, while LaPorta’s study only focused on force platform variables. So, we followed it with a study using a different sample of participants but the same shoe types to determine whether joint ranges of motion and mechanical outputs can change following a switch between minimalist and standard athletic shoes and whether such changes can contribute to vertical jump performance changes in males and females.19 That study’s results revealed minimalist shoes were not associated with a meaningful change in vertical jump performance, but were associated with smaller magnitudes of knee joint power and work and larger magnitudes of ankle joint work compared to standard athletic shoes. This result supported our 2015 paper’s detection of altered jump strategies when switching to minimalist shoes.

An interesting result from Smith et al.19 was that ~39% of the sample displayed greater jump performances in minimalist shoes versus standard athletic shoes. This led me to believe that questions related to shoe effects during jumping are not adequately answered using conventional group-level statistical analyses (i.e., generalizing the sample before analysis). So, I recently revisited the vertical jump data from the 2015 paper17 and used a replicated single-subject approach20 to explore individual jump performance responses21 while also including additional jump strategy variables (e.g., phase durations) in response to trends in the current literature. Results of the replicated single-subject analysis revealed that all force, time, and muscle activation variables changed in most participants when switching between minimalist shoes, conventional athletic shoes, and barefoot. Moreover, ~47% of the sample exhibited different jump heights across the shoe types.

In my opinion, some individuals and athletes can absolutely see immediate benefits to their jump performance by a change to (or from) minimalist shoes, says @johnharry76. Share on XWhile it remains difficult to establish a consensus on the manner in which minimalist shoes affect jump strategy and performance, it is quite clear, in my opinion, that shoe responses are specific to each individual and some individuals and athletes can absolutely see immediate benefits to their jump performances by a change to (or from) minimalist shoes. The next logical step toward developing a consensus for the way in which individuals respond to minimalist shoes is to use thorough sub-grouping strategies to tease out any characteristics of those who respond positively to minimalist shoes.

Freelap USA: Many teams are looking at creating force during jump testing, and you have some insight into landings. What can we learn about the landing component of testing? Is there anything that we can learn about athlete force reduction strategies and training or even performance?

John Harry: I think any team or coach conducting jump tests should always study the landing because the vertical jump is essentially a two-for-one test due to the requisite landing. From my perspective, there are two main goals as it relates to landing. The first is maintenance or enhancement of performance, defined by the time it takes to stop downward motion, because athletes must be prepared for whatever type of secondary movement is required in their time-constrained performance environment. The second is reduction of overuse injury risk, as my experiences consulting with teams suggest all coaches and practitioners want to keep their athletes healthy and prepared to perform on the pitch/court.

Landing performance, as I have defined it, is perhaps the most overlooked quality of landing in the scientific literature. This is an area that needs a lot more work to really understand how athletes can terminate downward motion more quickly so that intervention strategies can be explored and presented.

I think any team or coach conducting jump tests should always study the landing because the vertical jump is essentially a 2-for-1 test due to the requisite landing, says @johnharry76. Share on XWhat we’ve learned in my lab is that those who can terminate downward motion sooner utilize less hip and greater knee and ankle joint contributions to total lower body energy absorption during the loading phase of landing (i.e., first ~0.75 seconds), which appears to be due to increased plantar flexion at ground contact.22 This result is valuable because energy is best absorbed during loading when relying on the more distal joints.

Perhaps the most important result we observed as it relates to coaches and practitioners with access to only force platforms, was that a higher rate of impact force attenuation during the attenuation phase (i.e., time between the peak impact force and the end of downward motion) also seems to distinguish individuals with faster versus slower landings. This appears due to the aforementioned results in addition to increased knee joint contributions to total lower body energy absorption during the attenuation phase. My preliminary suspicion from these results is that coaches and practitioners can use force platform data to calculate landing time and the rate of impact force attenuation to explain changes in landing performance without mandatorily studying joint energy absorption strategies using motion capture systems.

Overuse injury risk can also be partially assessed through impact forces, which occur very rapidly and tend to exceed four times body weight during typical vertical jump landings22. Super-maximal training-style landings (i.e., landings from platforms elevated to heights exceeding maximum jump height) can reach as high as 11 times body weight.23 These large impact forces are attenuated through lower body joint energy absorption, and risks for overuse injuries can increase when repetitively attenuating and absorbing larger magnitudes of impact force and energy, respectively.

As it may not be feasible to reduce the frequency of landings performed in training because athletes must be adequately prepared to perform many maximal effort landings during competition24-26, the most feasible way to try and reduce landing-related injury potential is to reduce impact forces and refine the lower body’s energy absorption strategy (i.e., organization of muscular efforts). A simple way to acutely realize this is to prescribe an external focus of attention. For example, we have shown27 that using an external focus (pushing against the ground as rapidly as possible upon ground contact) reduces the peak impact force magnitude and increases the contribution of the knee joint to the total amount of energy absorbed by the lower body joints during the loading phase of landing in males and females when compared to using an internal focus (flexing the knees as rapidly as possible upon ground contact).

This is important because both the loading rate (i.e., yank or RFD during the loading phase) and the total amount of energy absorbed across the hip, knee, and ankle joints do not differ between foci. Any increase in the knee contribution is therefore ideal because the knee joint is the dominant lower body joint during both phases (loading and attenuation) of landing22. From these results, my preliminary speculation is that coaches and practitioners relying on force platforms for landing assessments could conclude that development/refinement of these joint energy absorption strategies will occur with an external focus as long as the loading rate (i.e., yank during the loading phase) does not change.

Collectively, these results suggest that, for athletes seeking to increase landing performance, reduce overuse injury risk, or both, increasing eccentric strength should be a training emphasis because it should increase the integrity and control of the lower body joints. I’ve been out of the practitioner’s game for many years now, but I think a safe place to start working for maximized landing performance would be to try to refine the athlete’s landing strategy such that the energy absorption strategy mentioned here is observed using at least force platform data to reveal targeted changes or maintenance of landing time, peak impact force, loading rate, and rate of force attenuation as appropriate. Once that is accomplished, it may be beneficial to prescribe loaded jump landings to stimulate rapid eccentric force attenuation and energy absorption abilities. However, coaches and practitioners working with mixed-sex populations should be aware that females use different landing strategies than males27, as evidenced by greater impact forces, despite lesser jump-landing height, and lesser knee and greater ankle joint contributions to lower body work (i.e., an ankle-dominant strategy).

Freelap USA: Speaking of jumping, the aerial component for athletes with rotation and other motions can really make extrapolation to landings even more complicated. With soccer and dance research, what can we learn about the risk of injuries?

John Harry: Aerial rotations really do complicate things, and they’re quite common during competition on the pitch/court. Surprisingly, there’s not a whole lot of research on how aerial rotations impact both jumping and landing performance and injury risk. We’ve tried to fill this literature gap by studying vertical jumps with aerial rotations in collegiate male footballers28,29.

A vertical jump with a 180-degree aerial rotation is accomplished by horizontal coupling forces applied into the ground. Interestingly, the force couple driving rotation occurs along the anterior-posterior axis and not the medial-lateral axis.28Specifically, the rotation occurs because one limb applies more force posteriorly into the ground than does the opposite limb, which leads to the aerial rotation and reduced jump height. In addition, jump explosiveness decreases because of the reduced jump height, even though the durations of the countermovement and upward/concentric phases remain consistent and much greater peak vertical force production occurs. We suspect this means athletes exert greater effort to jump with a rotation, but the added effort is insufficient to retain the performance level of jumps without rotation.

When landing from a vertical jump with a 180-degree aerial rotation, horizontal force coupling is applied in both the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral directions, indicating the strategy to stop rotation is different than the strategy to create rotation29. Still, the anterior-posterior force couple dominates the force coupling actions applied to terminate the rotation upon ground contact. From an overuse injury risk perspective, greater peak impact forces and shorter times to the peak impact force occur when landing from the jump with rotation. This is very important because the jump with rotation coincides with lesser jump-landing height and should therefore have smaller impact force magnitudes.

What this tells us is that the need to rotate when jumping compromises the athlete’s landing strategy such that greater external stress occurs even though the landing should be less “stressful.” Given the results mentioned previously for landing performance and overuse injury risk, landing from a jump with rotation appears to expose athletes to greater overuse skeletal injury potential (i.e., tarsal/metatarsal stress fractures). Focused training could be required to refine athletes’ landing strategies during jumps with rotation so that the peak impact forces and times to peak impact force can decrease.

Given the results mentioned previously for landing performance and overuse injury risk, landing from a jump within rotation appears to expose athletes to greater overuse skeletal injury potential. Share on XAn important result mentioned above was that landing performance (time to stop downward motion) was maintained when landing from a jump with versus without rotation. This suggests athletes are similarly prepared to execute secondary movements after completing landings with and without rotation, which would be a desirable ability among athletes participating in ground-based sports. What coaches and practitioners should be aware of, however, is the time required for the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral coupling forces to return to zero relative to the time required to stop downward motion.

Our evidence shows that the collegiate male footballers we studied were able to reduce those coupling forces by the end of the landing. Athletes who show relatively large coupling forces at the end of the landing might need focused work to more quickly complete the coupling force applications so that those forces are not in need of continued attenuation after stopping downward motion. This can help ensure that secondary movements can be quickly performed as needed without overt risks for injury that would otherwise be present if an athlete has to attenuate horizontal forces to complete the rotation while concurrently trying to apply force in an attempt to start the secondary movement.

Freelap USA: Loaded backpacks and weight vests are common tools for tactical training. Is it redundant to train with heavier-than-normal vests or is it a good idea to help athletes and tactical professionals to load heavier than normal in training?

John Harry: I can’t speak to weighted vest use for all types of athletic qualities, but I am familiar with its effect on jumping and landing. From that perspective, I do think weighted vest use during training can be a decent short-term option to apply stimulating loads2 or vary the way stimulating loads are prescribed. But, as with most training applications, I think the answer to this specific question is “it depends” on the goals and performance demands of the athlete(s).

I say this for two reasons. First, research indicates ~10% to 13% of body weight30-32 should be added to the weighted vest to increase jump height, and this magnitude of weight may not be a stimulating load for some athletes. Second, the weighted vest, which is usually positioned in some fashion over the trunk, can alter certain athletes’ trunk positioning and injury risk, particularly during landing from a raised platform. Specifically, trunk positioning was altered so much in some individuals that joint loading and energy absorption was notably greater versus those whose trunk position was not altered in the same way.33,34

While unpublished data from my lab confirmed that weighted vests encourage altered trunk angular positioning in some participants during jump landings, elevated injury risks associated with joint energy absorption might not characterize one trunk-specific response versus the other when landing from a jump. Still, Kulas’ work presents a rationale for caution when using weighted vests.

Recent studies published out of my lab provide some rationale for how weighted vest use can stimulate increases in jump height when ~10% body weight is used. For example, we found that weighted vest use causes participants to slightly increase both relative force application at zero velocity, which represents the amount of energy stored in the system, and relative concentric energy production about the hip, knee, and ankle joints.14 Something that coaches and practitioners should be aware of, however, is that these beneficial changes in energy storage and concentric mechanical output occur alongside slightly elongated eccentric and concentric phase durations. This means that adding ~10% body mass via a weighted vest might not be an ideal intervention to improve jumping explosiveness because it stimulates “slower” jumps. Although the changes we observed were small in magnitude, they do indicate that we should cautiously employ chronic weighted vest use in jump training, at least when increased explosiveness is a desired outcome.

At face value, it may seem logical that adding an external load to an athlete during jump landings will increase the “intensity” of landing. However, performing jump landings with either small weighted vest loads35,36 or large barbell loads37 is associated with unchanged or even smaller peak and average impact forces than when performing jump landings without external loads. While this is a good result from an impact force perspective, my lab’s work35 also revealed that both the time to stop downward motion and the total amount of lower body joint energy absorption can increase when wearing a weighted vest with ~10% body mass even though jump-landing height and peak impact force decrease. Specifically, the hip and ankle joints drive the increase in total lower body energy absorption.

Interestingly, the total amount of mechanical energy developed by the time of ground contact was the same when landing from vertical jumps with versus without a weighted vest. Because impact forces decrease but landing time and total lower body energy absorption increase, athletes can have a perception of greater demands when wearing a weighted vest. The result of this perception is a modified landing strategy making the hip and ankle musculature work more vigorously than necessary. Ultimately, this means that weighted vest use could actually increase the potential for overuse musculo-tendinous injury in the hip and ankle musculature in spite of reduced risks for overuse skeletal injury (e.g., impact force-related stress fracture). This might be an unavoidable quality of all loaded jump movements and therefore not a hazardous result, but I do think it’s something coaches and practitioners should be aware of prior to implementing weighted vests.

Females appear to respond to weighted vests differently than males do when performing jump landings, says @johnharry76. Share on XIt is well known that males and females employ distinct landing strategies, and females are exposed to greater landing-related injury risks. However, our study35 revealed that females display greater magnitudes of hip joint energy absorption (increase hip muscular effort) during landings with versus without a weighted vest, but males did not show such changes. Thus, females appear to respond to weighted vests differently than males do when performing jump landings. These sex-specific perceptions and pooled-sex responses to weighted jump landings should be considered when designing sex-specific training interventions that involve weighted vest use during jump landings.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Lin, D. C., McGowan, C. P., Blum, K. P., and Ting, L. H. “Yank: the time derivative of force is an important biomechanical variable in sensorimotor systems.” Journal of Experimental Biology. 2019;222(18), jeb180414.

2. Zatsiorsky, V. M. and Kraemer, W. J. Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. 2006.

3. Harry, J. R., Barker, L. A., James, C. R., and Dufek, J. S. “Performance Differences Among Skilled Soccer Players of Different Playing Positions During Vertical Jumping and Landing.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2018;32(2):304-312.

4. Rice, P. E., Goodman, C. L., Capps, C. R., Triplett, N. T., Erickson, T. M., and McBride, J. M. “Force–and power–time curve comparison during jumping between strength-matched male and female basketball players.” European Journal of Sport Science. 2017;17(3):286-293.

5. Chowning, L. D., Krzyszkowski, J., and Harry, J. R. “Maximalist shoes do not alter performance or joint mechanical output during the countermovement jump.” Journal of Sports Sciences, In Press. 2020.

6. Cormie, P., McGuigan, M. R., and Newton, R. U. “Changes in the eccentric phase contribute to improved stretch-shorten cycle performance after training.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2010;42(9):1731-1744.

7. Kijowksi, K. N., Capps, C. R., Goodman, C. L., et al. “Short-term resistance and plyometric training improves eccentric phase kinetics in jumping.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2015;29(8):2186-2196.

8. Harry, J. R., Barker, L. A., and Paquette, M. R. “A Joint Power Approach to Identify Countermovement Jump Phases Using Force Platforms.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2020;52(4):993-1000.

9. McMahon, J., Suchomel, T. J., Lake, J., and Comfort, P. “Understanding the key phases of the countermovement jump force-time curve.” Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2018;40(4):96-106.

10. Street, G., McMillan, S., Board, W., Rasmussen, M., and Heneghan, J. M. “Sources of error in determining countermovement jump height with the impulse method.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 2001;17(1):43-54.

11. Sole, C. J., Mizuguchi, S., Sato, K., Moir, G. L., and Stone, M. H. “Phase characteristics of the countermovement jump force-time curve: A comparison of athletes by jumping ability.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2018;32(4):1155-1165.

12. Krzyszkowski, J., Chowning, L. D., and Harry, J. R. “Phase-specific predictors of countermovement jump performance that distinguish good from poor jumpers.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, In Press. 2020.

13. Harry, J. R., Barker, L. A., Tinsley, G. M., et al. “Relationships among countermovement vertical jump performance metrics, strategy variables, and inter-limb asymmetry in females.” Submitted for Publication.

14. Harry, J. R., Barker, L. A., & Paquette, M. R. “Sex and acute weighted vest differences in force production and joint work during countermovement vertical jumping.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2019;37(12):1318-1326.

15. Cohen, D. D., Restrepo, A., Richter, C., et al. “Less opinion, more data: Detraining of specific neuromuscular qualities in elite footballers during COVID-19 quarantine.” Submitted for Publication. 2020.

16. Harry, J. R., Krzyszkowski, J., and Chowning, L. “Phase-specific force and time predictors of standing long jump performance.” Submitted for Publication. 2020.

17. Harry, J. R., Paquette, M. R., Caia, J., Townsend, R. J., Weiss, L. W., and Schilling, B. K. “Effects of footwear condition on maximal jumping performance.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2015;29(6):1657-1665. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000813

18. LaPorta, J. W., Brown, L. E., Coburn, J. W., et al. “Effects of different footwear on vertical jump and landing parameters.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research / National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2013;27(3):733-737. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318280c9ce

19. Smith, R. E., Paquette, M. R., Harry, J. R., Powell, D. W., and Weiss, L. W. “Footwear and sex differences in performance and joint kinetics during maximal vertical jumping.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2020;34(6):1634-1642.

20. Bates, B. T. “Single-subject methodology: an alternative approach.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1996;28(5):631-638.

21. Harry, J. R., Eggleston, J. D., Dufek, J. S., and James, C. R. “Footwear alters performance and muscle activation during vertical jumping.” Submitted for Publication. 2020.

22. Harry, J. R., Barker, L. A., Eggleston, J. D., and Dufek, J. S. “Evaluating performance during maximum effort vertical jump landings.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 2018;34(5):403-309.

23. McNitt-Gray, J. “Kinematics and Impulse Characteristics of Drop Landing from Three Heights.” International Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 1991;7(2):201-224.

24. Lian, O., Engebretsen, L., Ovrebo, R. V., and Bahr, R. “Characteristics of the leg extensors in male volleyball players with jumper’s knee.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1996;24(3):380-385.

25. McClay, I. S., Robinson, J. R., Andriacchi, T. P., et al. “A profile of ground reaction forces in professional basketball.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 1994;10(3):222-236.

26. Taylor, J. B., James, N., and Mellalieu, S. D. “Notational analysis of corner kicks in English premier league soccer.” Science and Football V: The Proceedings of the Fifth World Congress on Football. 2005:229-234.

27. Harry, J. R., Lanier, R., Nunley, B., and Blinch, J. “Focus of attention effects on lower extremity biomechanics during vertical jump landings.” Human Movement Science. 2019;68: 102521.

28. Barker, L. A., Harry, J. R., Dufek, J. S., and Mercer, J. A. “Aerial Rotation Effects on Vertical Jump Performance Among Highly Skilled Collegiate Soccer Players.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017;31(4):932-938.

29. Harry, J. R., Barker, L. A., Mercer, J. A., & Dufek, J. S. “Vertical and Horizontal Impact Force Comparison During Jump-Landings With and Without Rotation in NCAA Division 1 Male Soccer Players.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017;31(7):1780-1786.

30. Bosco, C., Zanon, S., Rusko, H., et al. “The influence of extra load on the mechanical behavior of skeletal muscle.” European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 1984;53(2):149-154.

31. Khlifa, R., Aouadi, R., Hermassi, S., et al. “Effects of a plyometric training program with and without added load on jumping ability in basketball players.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research / National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2010;24(11):2955-2961. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e37fbe

32. Thompsen, A. G., Kackley, T., Palumbo, M. A., and Faigenbaum, A. D. “Acute Effects of Different Warm-Up Protocols with and without a Weighted Vest on Jumping Performance in Athletic Women.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Allen Press Publishing Services Inc.). 2007;21(1):52-56.

33. Kulas, A. S., Hortobagyi, T., and Devita, P. “The interaction of trunk-load and trunk-position adaptations on knee anterior shear and hamstrings muscle forces during landing.” Journal of Athletic Training. 2010;45(1):5-15. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-45.1.5

34. Kulas, A. S., Zalewski, P., Hortobagyi, T., and DeVita, P. “Effects of added trunk load and corresponding trunk position adaptations on lower extremity biomechanics during drop-landings.” Journal of Biomechanics. 2008;41(1):180-185.

35. Harry, J. R., James, C. R., and Dufek, J. S. “Weighted vest effects on impact forces and joint work during vertical jump landings in men and women.” Human Movement Science. 2019;63:156-163.

36. Janssen, I., Sheppard, J. M., Dingley, A. A., Chapman, D. W., and Spratford, W. “Lower extremity kinematics and kinetics when landing from unloaded and loaded jumps.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 2012;28(6):687-693.

37. Lake, J. P., Mundy, P. D., Comfort, P., McMahon, J. J., Suchomel, T. J., and Carden, P. “The effect of barbell load on vertical jump landing force-time characteristics.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2018.