I’ve been training to jump higher ever since I can remember. For years, my main measurement tool was how high I could get my hand on a basketball net, then the rim, and eventually the square on the top of the backboard. In high school, running parallel to this, I began the magic of measurement via a crossbar suspended between two metal standards—an event known to many as “high jump.”

Our brains need what is known as “knowledge of result” or “KR,” as Frans Bosch often alludes to, in order to hit new levels of performance. Knowledge of result (how high did you jump/how far did you throw/how fast did you run) is what gives our subconscious mind the means to determine whether what we are doing in training is actually working. The subconscious mind often cares less in regards to many traditional cues and instructions.

Knowledge of result isn’t only numbers. It can also revolve around body positions, such as keeping the head fixed after clearing a hurdle, where the brain must self-organize a strategy for the body to work in this context.

A Jump Mat Helps Give Context to ‘Knowledge of Result’

In jumping for more than two decades, and coaching jumps for just over one decade now, I’ve realized how important it is to provide athletes with context and “knowledge of result” through a variety of means. This helps them understand how their bodies are working and adapting, not only on the conscious level, but also the subconscious one.

To this end, at age 24, I finally took a substantial leap and purchased a “Just Jump” mat. It was a significant investment for a poor graduate school student working for UPS and valet parking cars to make ends meet. (I actually thought that I could get the cost reimbursed at the time, and that I would be able to use the jump mat in tandem with the force plates at our biomechanics lab, but neither of these ended up happening.)

Contact times in jumping provide a more important ‘knowledge of result’ than height readings. Share on XThe Just Jump mat became one of my favorite tools for years to come, and all of my track athletes were tested on standing vertical jumps contrasted against the 4-jump test. We also used it quite often in the context of plyometric contacts—for the life of me, I don’t know why the plyometric function isn’t in the current system (it was in the old model). The KR that comes from contact times in jumping is, in my mind, probably more important than any sort of height reading as far as track jumpers (and jumpers of all types) are concerned.

Training With the Speed Mat

In terms of knowledge of result of testing though, there are a few areas where things can be better. It has been said (and I firmly believe it) that getting more data from doing fewer things is the optimal path leading to improved coaching intuition (as opposed to a little data on a lot of things, which just leads to confusion). This is one area where I was like a kid on Christmas morning when I started to utilize the Speed Mat in basic tests, such as the 4-jump counter-movement jumping and cadence. (It’s actually five jumps on the Speed Mat.)

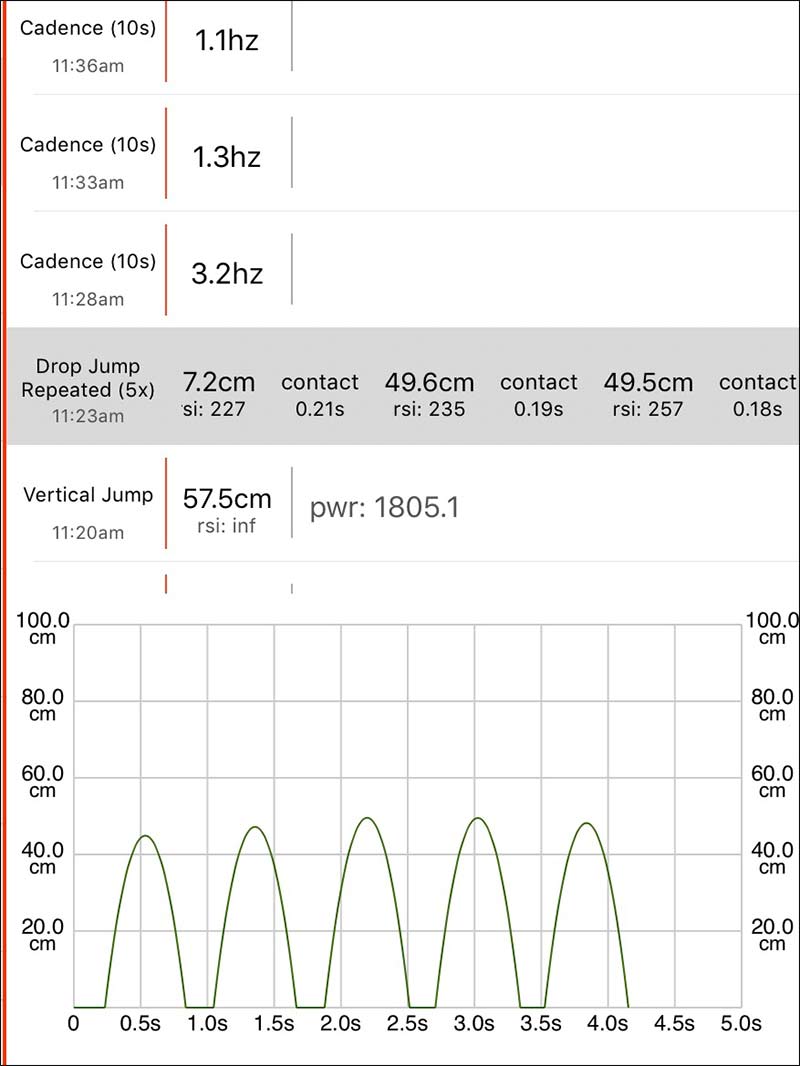

Here is what I mean. The Speed Mat offers tests such as vertical jump, assessing both height and power. It has a 5-jump option that enables you to track the wave pattern of each jump. (Did the athlete get better on each jump, i.e. a reactive athlete, or did they get worse? Or were they totally erratic, such as a player who just has no plyometric ability and needs to improve direction of force off the ground?)

Although the simple output box of the Just Jump gave effective data to coaches on a rather binary level, a lack of options on the same tests (and dropping plyometric contact time) was holding it back.

Not only does the Speed Mat have great “training = testing” features such as cadence and a single jump reactive strength index (RSI), but its app-based nature also allows an evolutionary process as we advance in these training and testing ideals. Although app-based systems do require an extra step in setup, they more than make up for it by being able to offer better tracking, and evolving over time with tests and metrics.

One thing I am looking forward to seeing down the line is Bosco’s 15-jump fast and slow twitch indicator test, as described to me by Henk Kraaijenhof. It’s a thing of beauty to get on a mat for 10 seconds and instantly have a good idea what your fast-to-slow twitch percentage is, as well as all the related implications for micro- and meso-cycle constructions.

In a more real-time view, the RSI function on the Speed Mat is a great “priming” modality for any plyometric session. As Curtis Taylor mentioned on Episode 21 of the Just Fly Performance Podcast, contact times are one of the first things he looks at when starting a plyometric program in fall training. If you coach the plyometric around the constraint of contact time, you know the muscle-tendon and motor-control layout you are building is one that an athlete can build on down the line.

In acute session training, I can use the Speed Mat to help athletes understand which combination of ground contact time and height will yield the optimal outcome, and then take this movement pattern to all other plyometrics done in the session. This is a great contextual tool for any coach.

If you are familiar with Charlie Weingroff, then you know his mantra of training = rehab and rehab = training. With jump testing, I think I have a model of testing = training and training = testing.

As far as testing and data go, I agree with what I’ve learned from Carl Valle, that you are winning if you can make the training the test, and therefore engage in minimal distractions before or through the course of the workout. I think we occasionally forget that we are, in fact, coaches, and our primary mission is to train athletes and not undertake a barrage of assessments through each workout.

Jump testing with the Speed Mat provides a model of testing = training and training = testing. Share on XIn addition to excess testing taking time, it can also become a distraction from the flow-state of training, and buying into the day’s work. After decades of the coaching game, I think we can agree that athletes who are continually cued or measured after every single exercise fall into movement paradigms that don’t lead to optimal results.

So, what are some aspects of the Speed Mat that I’ve found incredibly useful in my marriage of training and measuring?

- The alternation of power and maximal jump height options

- Using cadence for training or a canned test system under constant constraints

- RSI can set the tone

- Looking at the 5-jump in the context of RSI, peak power, and jump curve progression

Mental Gains and Alternating Quantification Types

One thing I’ve begun to understand over the years is the value of not measuring everything in the exact same way, over and over. When you get so hung up on one specific type of measurement, it can become de-motivational over time, especially when particular numbers become a self-fulfilling prophecy on the athlete’s end for the day’s work. Fluid periodization is certainly important, but the mental stress of having a singular key performance indicator at the beginning of each session can become a drag.

I’ve come to realize that when I suspect that athletes will be lower than average in a given exercise with attached feedback (such as a Kaiser jumper), I’ll alter the constraints of the test, or even cover up the output readout. This is so athletes won’t get discouraged if I’m trying to keep the intensity level of the strength session lower.

In the same vein, I really like that the Speed Mat has the capability of not only measuring vertical jump height (and it does so in metrics, which is a contrast to just jump or Western vertecs) but also vertical jump power. I’ll use the SpeedMat as an alternative vertical jump test because my athletes aren’t looking at the centimeters jumped, but rather the power, which is a function of their bodyweight and height. This gives them motivation for the day, even if their output is down, and keeps that intent of the drill, which is so important for continued progress.

Video 1: The Speed Mat doesn’t measure just vertical jump height, it also measures vertical jump power. When it’s used as an alternative vertical jump test, athletes look not at the centimeters jumped, but at their jump power, which gives them motivation even if their output is down.

Cadence and the Forgotten Art of Contact Time Overload and Rhythm

If I had to explain what data I’m most fond of when it comes to various force plate and jump mat tests, I’d say that contact time tells me more about an athlete’s ability to produce force usable in sport (particularly jumps) than absolute height does. I’ve had high jumpers who tested mediocre at pretty much every test in my battery, but had the ability to land a depth jump from a 60-70cm box with ninja-like qualities and also register plyometric contact times of .16-.17 on high hurdle hop drills.

In a similar vein, I’ve always enjoyed the lateral barrier hops exercise for time. This movement requires fine coordination of muscular contraction and relaxation, as well as fast vertical stiffness against resistance. There is also a lateral component, which is important for building sprint and jump stabilizers and synergists. Pre-tensioning is a must to get a good rate over the barrier, as muscle slack is the enemy of rapid angular joint velocities in the lower limbs in conjunction with vertical stiffness (sounds like a common linear activity we all know well).

To up the ante on this particular movement, a Speed Mat set to cadence can be utilized to give instant feedback on an athlete’s rate of movement.

Video 2: The lateral barrier hops exercise requires fine coordination, fast vertical stiffness, and pretensioning. Add to this movement by using a Speed Mat set to cadence, which gives instant feedback on the athlete’s rate of movement.

RSI Can Set the Tone

The RSI is a great way to set the tone for a workout, and you can use it as a contextual tool to improve the quality of the ground contacts in the rest of the plyometric workout. What I’ve found over time is that many athletes don’t ever get the sensory and quantitative feedback to understand what it’s like to get off the ground in under .20 seconds. The use of a feedback system, such as the RSI function on the Speed Mat, is a great way to start a session in a manner that allows athletes to “refer back to the warmup” to find a sensation that they can plug into their current plyometric activity.

Video 3: The RSI function on the Speed Mat is a great “priming” modality for any plyometric session. The feedback from the Speed Mat helps athletes understand what it’s like to get off the ground fast enough to get into reactive territory.

In this regard, RSI is a massive help. It’s also a great way to assess early over-reaching, since the highest order of speed strength and the length of foot contacts in every activity is the first thing to “go” when an athlete enters into heavy training. Even in these cases, athletes can still hit good barbell numbers, to the delight of the strength coach, whether or not the motor patterning that exists in this scenario is completely optimal. As with anything, the balance here is up to the planning scheme of the coach, whether it’s planned periods of creating a negative hormonal balance to overshoot later, or training that hangs its hat completely on the finest neural quality in the short (or long) term.

What Can the 5-Jump Tell You About Your Athletes?

Compared to a singular countermovement jump, a 5-jump tells us quite a bit about the ability to display force quickly (and accurately) in the vertical plane. A 5-jump is more informative of neuromuscular fatigue, since the highest order of speed strength is the first domino to fall when an athlete starts delving into the realm of overreaching. The wave of a 5-jump test is also a great way of telling, and training, an athlete’s level of coordination and accuracy in producing rapid vertical forces. If an athlete has trouble doing it once (Single response RSI jump), chances are that they will reach that neural edge rather quickly in the course of a multi-jump test, but it does really tell you what the athlete is prepared to do.

Video 4: A 5-jump test gives a lot of information on the ability to display force quickly on the vertical plane. This includes neuromuscular fatigue, since speed strength is the first thing to go when an athlete begins overreaching.

Generally speaking, anterior-chain dominant athletes have respectable vertical jumps, but somewhat poor 5 jumps. For posterior-chain dominant folks, it’s often the opposite.

A bonus with a multi-jump test is that athletes can’t cheat the landings quite as well, either. I consider a 5 jump an RSI test with a greater accuracy requirement.

An Efficient and Beneficial Training Solution

After training jumpers for many years in track and field and team sport, and even as slam-dunk specialists, I’ve come to understand where testing and training can merge and create more efficient and beneficial training solutions. In this regard, the Speed Mat is a valuable tool, and has unlimited potential within the scope of contact mat readouts.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

In addition to excess testing taking time, it can also become a distraction from the flow-state of training, and buying into the day’s work. After decades of the coaching game, I think we can agree that athletes who are continually cued or measured after every single exercise fall into movement paradigms that don’t lead to optimal results.