Strength coaches are obsessed with how fast athletes run, how high they jump, and how much they lift. After all, these numbers determine the ceiling of athletic potential…or do they? Consider the perplexing NFL Combine results of running back Chris Johnson and quarterback Tom Brady.

In the 2008 NFL Combine, Johnson ran the 40-yard dash in 4.24 seconds, tying the NFL’s all-time best, and soared 35 inches in the vertical jump. The Tennessee Titans drafted him in the first round. The payoff? Johnson rushed for over 1,000 yards in six seasons, racking up 2,006 yards in 2009. He was also the first player to reach 1,900 rushing yards and 400 receiving yards in the same season.

In the 2000 NFL Combine, Brady ran the 40 in 5.28 seconds and vertical jumped 24.5 inches. The New England Patriots drafted him in the sixth round. The payoff? Brady threw for 89,214 yards with 649 passing touchdowns, was voted the NFL’s Most Valuable Player three times, and won the Super Bowl seven times.

Are Tom Brady’s pedestrian numbers an odd exception and not the rule? Perhaps, but consider the results of one study involving 1,155 athletes who participated in the NFL Combine between 2005 and 2009. The researchers found that “regardless of position, the current battery of physical tests undertaken at the combine holds little value in predicting draft order.”

With such diverse results, it’s understandable that many sports coaches, not just football coaches, are skeptical about the value of testing. But perhaps it’s not so much that testing is worthless, but more that the tests used to measure athletic potential are often irrelevant.

A Closer Look at Speed

The 40-yard dash is considered the ultimate measure of a football player’s speed, but why? How often has anyone ever run 40 yards in a straight line in an NFL football game? Further, between 2010 and 2019, the average number of total rushing yards per game was 117, and the total passing yards was 234. Let’s consider another popular measurement of speed, the 100-meter sprint.

The 40-yard dash is considered the ultimate measure of a football player’s speed, but why? How often has anyone ever run 40 yards in a straight line in an NFL football game? Share on XThe title of “The Fastest Man in the World” is given to the winner of the 100 meters in the Olympic Games. However, sometimes it’s not the sprinters with the highest top speed who win in sprinting. Consider the controversial 100-meter finals at the 1988 Olympics featuring Carl Lewis and Ben Johnson.

Johnson won with a world record time of 9.79, even raising his arms before the finish, which may have slowed him down. Lewis was close behind at 9.92 but was later declared the gold medalist when Johnson was disqualified for doping. Surprisingly, the fastest 10-meter split for both athletes was .83 seconds. Johnson’s superior reaction time and rocket start gave him a huge .8-second advantage over Lewis for the first 20 meters, but both had the same lowest time for a 10-meter split.

Another unique aspect of the 100m is that most sprinters don’t reach top speed until about 65 meters. In his world-record 100m sprints in 2008 (9.69) and 2009 (9.58), Usain Bolt reached his top speed when he passed the 60-meter mark. Further, his time for the first 10 meters during his 9.58 record was .6 seconds slower than Johnson’s.

How could this data apply to football?

Although elite 100m sprinters are undoubtedly fast for the first 10 meters, the average run from scrimmage in the NFL in recent years is 5 yards. From these numbers, the wide receiver position might be best for sprinters such as Bolt and Lewis. Based on Johnson’s faster start (and being able to bench press 407 pounds for two reps!), the running back position might be best for Johnson. But hold on—a football coach should also consider focusing their recruiting efforts on hurdlers.

A hurdler must make minute adjustments during a race and be able to absorb, store, and redirect higher levels of force with each landing without sacrificing speed. Thus, the enhanced kinesthetic abilities from hurdling may transfer better to the gridiron than the ability to cover ground more quickly during a 100-meter sprint. But hold on again—there may be even better cross-training sports for football.

I joined the Air Force Academy as a strength coach in 1987. The head athletic trainer told me that in the early days of Air Force football, off-season conditioning consisted of the “skill” athletes playing basketball and the “linemen” wrestling. Perhaps this was not such a bad idea?

In the early days of Air Force football, off-season conditioning consisted of the ‘skill’ athletes playing basketball and the ‘linemen’ wrestling. Perhaps this wasn’t such a bad idea? Share on XBasketball players must not only be able to move and change directions quickly over short distances, but they must also react to the movements of others. In the 60m–100m events in sprinting, athletes stay in their lanes so they don’t interfere with the movement of their competitors. (Other than being a groovy-looking conditioning method, the lack of reaction to an opponent’s movements questions the value of many cone and ladder drills for football players.)

Wrestling, and many other forms of martial arts, make sense for linemen. At the Academy, I introduced the coaching staff to a martial artist who worked with NFL teams. He showed the coaches several hand movements to break holds and footwork techniques to move more effectively—we even made a video of these techniques to pass on to our current and future players. (By the way, one of this martial artist’s sales pitches to football teams was to have linemen try to tackle his girlfriend, an elite martial artist who often embarrassed them.)

Now that I’ve got you thinking, what resources are available for coaches to determine the best athletic fitness tests for your athletes? One innovative book that sparked my interest in sports-specific testing is Sportselection by Dr. Robert Arnot and Charles Gaines (1984).

The authors developed three major categories of sports-specific testing: The control (nervous) system, the heart-lung package, and body composition. Arnot and Gaines applied these categories to seven sports: alpine skiing, cross-country skiing, cycling, running, swimming, tennis, and windsurfing. Using their assessments, a parent can determine which of these sports their child is most likely to succeed in (and enjoy, as those with a physical advantage are often prone to enjoy a sport more).

One problem with Sportselection is that it only addressed the requirements of a few individual sports. However, there’s no stopping a coach from developing a method to assess other individual sports or even team sports. Let me show you how I did it with football.

The Football Equation

In the case of football players Johnson and Brady, their positions required different skill sets. The question I had to answer as a strength coach was, “What tests are most relevant for each position?”

Before answering, it’s necessary to distinguish between testing for run-oriented and throwing-oriented teams. The Academy had a “4 yards and a cloud of dust” offense, and the skill requirements for many offensive positions differ from a passing team.

Our wide receivers needed to be able to block, our offensive linemen needed exceptional lateral speed to pull, and our quarterbacks needed to scramble. In the season where we upset Ohio State in the Liberty Bowl, our quarterback averaged only 30 yards a game passing and didn’t throw a single touchdown pass all year. We actually had one game where the kicker threw for more yards than our quarterback when he fumbled the snap from center and passed the ball! My favorite slogan to describe our approach to football is: “Passing is for cowards!”

To determine the best predictor lifts and field tests for our football team, I enlisted the services of the Air Force Academy’s math department. My data included our primary lifts in the weight room, our field tests (such as the 40-yard dash and vertical jump), and our military fitness tests (such as sit-ups and the standing board jump). I only used data from the top three athletes in each position because these athletes were most likely to see playing time in a game. Thus, if our top three linebackers had exceptional results in the back squat, the back squat represented a strong correlation.

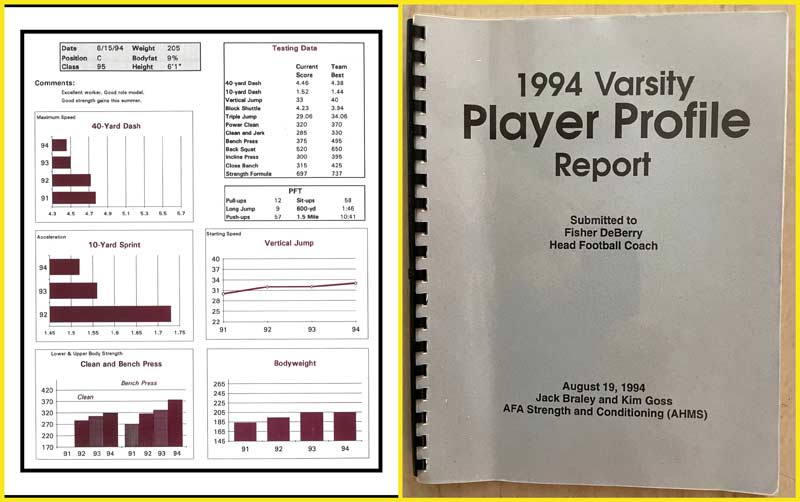

To determine the best predictor lifts and field tests for our football team, I enlisted the services of the Air Force Academy’s math department. Share on XAn example of the data we used is summarized in image 3, an Athletic Fitness Player Profile Report of one of our centers on the AFA football team. One feature of this report was that a coach not only sees each athlete’s current testing results but the progression of their testing results throughout their entire athletic career.

With the help of our math consultants, I could determine which lifts or field tests an athlete needed to focus on. (By the way, the math department was thrilled to help. I wonder how many Linear Algebra classes ended with the professors telling their students, “I need to release you 10 minutes early—the Falcon football team needs me!”)

Using data collected over three years, our number crunchers came up with some interesting results, not just in transferring athletic fitness testing to performance but correlations of one field test to another. For example, they found a strong correlation between the 40-yard dash and a two-leg triple jump. Let me explain.

We found that those who excelled in the triple jump also excelled in the 40. With athletes who did not possess good elastic strength (and thus the ability to accelerate in the 40), the results of each of the three jumps varied little. You might see a sequence of 8 feet, 8 feet, 8 feet. Athletes possessing exceptional elastic strength might display patterns of 8 feet, 10 feet, and 11 feet. Again, both athletes achieved the same result in the first jump, but exceptional elastic strength enabled the second athlete to jump farther on the second jump and even further on the third.

One of the issues with 40-yard dash testing is that athletes would (perhaps subconsciously?) hold back in the intensity of their weight workouts the week before testing to ensure they were not fatigued going into the test. Athletes were not so concerned about fatigue or soreness going into a jump test, so we could assess their ability to accelerate more frequently.

Although you would expect that improving all the field results would be good, there are cases in football when failing to make progress in sprinting speed and jumping ability is acceptable—case in point: the Lewis Formula.

Power Factor Testing: The Lewis Formula

There is no question that Saquon Barkley is a powerful runner. In his rookie season with the New York Giants, he rushed for 1,307 yards with a 5-yards-per-run average. He also performed remarkably in tests of strength and jumping ability. You can watch a YouTube video of Saquon Barkley cleaning 405 pounds in college, and in the 2018 NFL Combine, he vertical jumped 41 inches. But which test is better, the clean or the vertical jump? The answer is both.

At the AFA, our math consultants determined that the No. 1 test for determining the physical abilities of a lineman was the Lewis Formula. We also found that the formula was more relevant to fullbacks and linebackers than wide receivers and cornerbacks.

I first read about the Lewis Formula from sports scientists Mike Stone, Ph.D., and Harold O’Bryant, Ph.D., in their classic exercise science textbook, Weight Training: A Scientific Approach. They said, “The vertical jump is not a valid indication of leg and hip power unless mass and time are taken into consideration.” They followed this comment by introducing the Lewis Formula, a power index that solves this dilemma by using the vertical jump and body weight.

The Lewis Formula is represented by a nomogram containing three parallel vertical lines. On the left is body weight, on the right is the vertical jump, and where they intersect in the middle represents power. Using a straight ruler, a strength coach could determine if an athlete could generate more power by increasing their vertical jump (plyometrics) by 2 inches or increasing their body weight (higher-rep bodybuilding training) by 10 pounds.

Video 1: Weightlifter Christian Rivera demonstrates his vertical jumping ability and single-leg strength.

A practical example of applying the Lewis Formula is with Air Force Academy graduate Steve Russ. As a freshman, Russ recorded one of the fastest 40s, not just for the freshmen but for the entire team. He was 6-feet-4 and probably would have been a tight end on just about any other college team, but a more pressing need for us was a big body on defense (again, passing is for cowards). For Russ, the best way to increase his Lewis Formula was to increase his body weight, as he already had an excellent vertical jump.

Over the next four years, Russ improved his vertical jump from 31 to 35 inches but made minimal improvements in his 40- and 10-yard sprint times. But that was okay because Russ packed on approximately 50 pounds of muscle while maintaining a body fat of 10%. Also, during his four years with us, his clean went from 220 pounds to 335, and his bench press from 260 to 370. He thus became an irresistible force to compete against the immovable objects on our opponent’s offensive lines. Further, the Denver Broncos drafted Russ in the seventh round in 1997. He played for three years, including in 1999 when the Broncos won the Super Bowl, and he is now the Linebacker Coach for the Washington Commanders.

Fine-Tuning Performance with the Athletic Index

For strength assessments, we relied on the results of three lifts: clean, bench press, and back squat; we also considered body weight to assess relative strength. By the way, I wasn’t a fan of in-season “maintenance workouts.” Instead, I followed the in-season volume/intensity recommendations of legendary strength coach Charles R. Poliquin, which enabled many of our athletes to break personal records, even in the clean and squat, during the season.

We kept the coaches abreast of each athlete’s progress, and the best performances were recognized on large record boards posted throughout the gym. Awards such as “Mr. Intensity” were given to athletes who stood out for their work ethic and leadership in the weight room. One recipient of the Mr. Intensity award was Chris Gizzi.

In his first year with us, Gizzi increased his clean from 280 to 325, his vertical jump from 33 inches to 36, and his body weight from 195 to 221 at 8% body fat. Gizzi eventually cleaned 379 pounds and vertical jumped 39 inches at a body weight of 233. Gizzi played in the NFL and is currently the Strength and Conditioning Coordinator for the Green Bay Packers.

For the “skilled” players, I developed an “Athletic Index” that assessed the overall athletic ability of a football player. Rather than relying on one test, I took five field tests representing the basic athletic skills of running, jumping, and muscular endurance. (A comprehensive resource on tests to assess athletic performance is Physiological Tests for Elite Athletes, 2nd Edition (2012) by the Australian Sports Commission. It was first published in 2000. It was updated in 2012 and contains assessments for 18 sports; unfortunately, not American football.)

I developed an Athletic Index that assessed a football player’s overall athletic ability. It relies on five field tests representing the basic skills of running, jumping, and muscular endurance. Share on XFor each test on the Athletic Index, I established a point value, up to 20 points, based on the best performances on the team. For example, let’s say the best vertical jump on the team was 40 inches. The point value would be distributed as follows:

Jump Height Points

40 20

39.5 19

39 18

…and so on

I used 20 points as the max value because 20×5 equals 100, so one athlete may have an Athletic Index of 90 points and another 85 points. Working on an athlete’s weakness is the fastest way to improve an overall score. Let’s look at one variable considered vital for nearly every position in football: lateral speed.

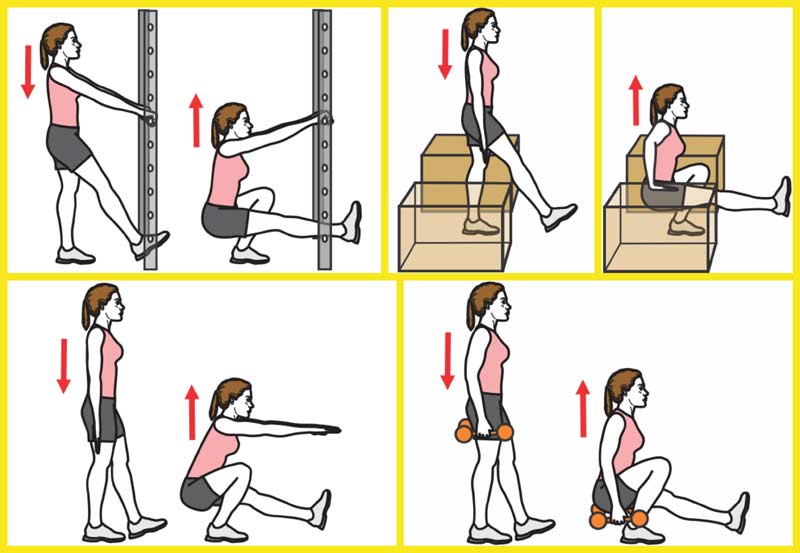

Because you briefly support yourself primarily on one leg when you change directions, single-leg squats are one strength training exercise to improve lateral speed. I like to start with assisted single-leg squats followed by non-assisted single-leg squats. Image 4 shows a progression of four single-leg squats, going from assisted squats to an unassisted version using weights.

On the field, you can perform many challenging exercises to increase the work of the muscles involved in lower body stability. Video 2 shows one exercise that involves fast eccentrics of muscles involved in lateral movement.

Video 2. In-and-out squat hops on an incline is a challenging exercise using fast eccentrics to enhance lateral speed.

I found the Athletic Index was most applicable to our “skill” players. For this reason, we had two basic workouts. The linemen would lift four days a week and do running and plyometrics once a week, and the skill players would lift three days a week and do running and plyometrics twice a week. If a lineman’s Athletic Index score was particularly low, he could briefly switch to the skill position workout to become an overall better athlete. Likewise, a physically weak skill player could briefly do the lineman workout to add strength and muscle.

Of course, you can expand an Athletic Index with additional tests. You could have 10 tests with a maximum value of 10 points per test. I also made an index that incorporated several core lifts, calling it the Football Index.

Today, considerable technology is available to take athletic fitness testing to the next level (certainly far exceeding what I did 30 years ago), precisely measuring physical qualities that could not be adequately measured before. Force plate technology is now being used at Brown University, where I’ve been coaching for several years. And my colleague Paul Gagné, a strength coach and posturologist, has been using force plates with his elite athletes to test their athletic preparedness for many years (video 3).

Video 3. Force plate technology can take athletic fitness to higher levels. Here Coach Paul Gagné uses a force plate to assess and train body awareness with Chloé Dufour-Lapointe, Olympic silver medalist in freestyle mogul skiing at the 2014 Olympic Games.

Moving on, in addition to individual testing reports, we would give the coaching staff team reports with the cooperation of our exercise science lab and sports medicine staff.

Team Reports

As with any sports medicine department, the AFA tracked every injury they treated. In 1992, they gave me a report summarizing the number of injuries they treated on the football team from 1988 to 1992. Over these five years, the number of injuries decreased linearly by 60%! Such results helped us earn the support of our sports coaches.

As a bonus, our sports medicine staff could determine approximately when an injury occurred during practice or a game. Falcon Head Football Coach Fisher DeBerry was known for his inspirational (and rather lengthy) post-practice reviews. We found that an exceptionally high percentage of injuries occur in the last 15 minutes of football practice, so we suggested that Coach DeBerry give part of his review in the middle of practice to allow the athletes to rest and recover. Although many variables are associated with injuries, the decrease in visits to the trainers during the first full year after we made this change was 18.75% (again, with a 60% decrease over five years).

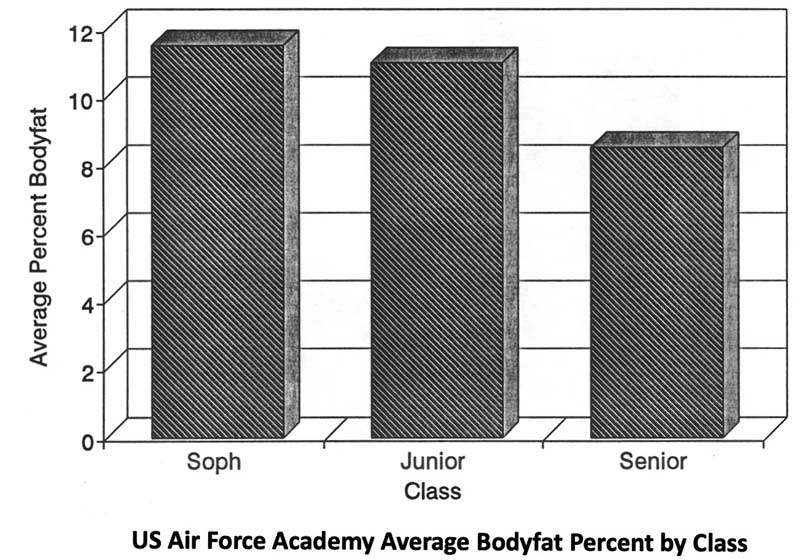

Body composition testing was also crucial at the Academy. Let’s say an athlete needs to improve their running speed or jumping ability. Because you can’t flex fat, you want your athletes to have low body fat levels. Want proof? Have an athlete run several 20-, 30-, or 40-yard sprints, alternating between wearing a 5- or 10-pound weight vest and running without one. Or have them perform several vertical jumps with and without additional weight. You may be surprised at how much just 5 pounds can affect running speed and jumping ability.

Speed is a primary concern in football, but it’s more challenging for lighter athletes to block and tackle heavier athletes. Share on XSpeed is a primary concern in football, but it’s more challenging for lighter athletes to block and tackle heavier athletes (in fact, we had one game in which the opposing team’s quarterback weighed more than any of our defensive linemen!). As such, our linemen needed exceptional stamina when faced with larger opponents (which was pretty much everybody we played).

How did we do at the AFA for turning our athletes into lean, mean football machines? Consider image 5, a team report showing our football players’ average body fat levels, including linemen, during a three-year period. Note that these are averages, and the percentage decreased each year. By the way, Jack Braley, the head strength coach at the AFA, was a master at skin calipers for determining body fat. He frequently compared his results to athletes who did hydrostatic (underwater) weighing in our exercise science lab and was usually spot on.

While putting this much work into testing may seem extreme, most colleges (and many high schools) have sufficient resources to enact a comprehensive testing program with their athletes. Assign a team manager or intern to evaluate testing results and get the school’s math, computer science, exercise science, and sports medicine departments involved. From there, see how you can use that data to help your athletes reach higher levels of athletic superiority.

Takeaways

- Determine what lifts and field tests are most relevant to your sport. Use current testing research and experiment with tests you believe are important.

- Share the results of your tests with sports coaches to encourage them to promote your program. Provide them with individual and team testing data.

- Use testing results to monitor the effectiveness of your program. If your athletes are not getting better during testing periods, change your program.

- Consider that many tests to determine athletic preparedness are inexpensive and require little or no equipment. If you have the budget for new testing technology, go for it!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

“Chris Johnson Prospect Info.”

“Tom Brady NFL Combine Highlights.”

Robbins, Daniel W. “The National Football League (NFL) combine: Does Normalized Data Better Predict Performance in the NFL Draft?” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2010;24(11):2888–2899.

“Development of average offensive yards per game (rushing/passing) in the NFL from 1950 to 2021.”

Lee, Jimson. “Add Up the Fastest 10 meter Splits and You Get…”

Royal, Darrell. Quote: “People call the split-T the ‘four-yards-and-cloud-of-dust’ offense.” Hickman, Herman. Sports Illustrated, September 23, 1957. (Note: There is insufficient evidence that this was the first reference to this quote.)

Arnot, R. and Gaines, R. Sportselection, Penguin Books. 1984. (Note: Title was later changed to Sportstalent.)

Poliquin, Charles R. Personnel communication, 1988.

Boly, Jake. “Penn State Running Back Saquon Barkley Just Cleaned 405 Lbs.” BarBend, 6/30/17.

Stone, Michael and O’Bryant, Harold. Weight Training: A Scientific Approach, Burgess International Group, Inc. 1984, pp. 166–168.

Goss, Kim. “They Call Him Mr. Intensity.” Bigger Faster Stronger, Winter 1977.

Physiological Tests for Elite Athletes, 2nd Edition, Australian Sports Commission. Human Kinetics, 2012.